Apollinaire seems to me the best of the “poets of the future” in this century. His entire Oeuvre should really be called A la recherche de l’avenir. Although he was born in 1880 and died in 1918 and thus spent less than two decades in the century with which he’s so closely identified, it is the search for the future—that is, the meaning of the arts in the twentieth century—that was to give his brief mercurial life its underlying stability and his poems their distinctive gaiety and pessimism. He thought of art us a battlefield, but with comrades rather than enemies—the enemies were in fact simply the people who couldn’t see the future or understand it. And Apollinaire’s battle was to make the future clear to himself and to others. His best poems—poems like “Les collines,” “Vendemiare,” “La jolle rousse.” “Zone,” “La Maison des Marts“—have about them the force of prophecy, are extravagant visions, vatic chants, commingling of the carnal and celestial, yet rendered in an extremely simple voice; the language itself is not simple, or is simple only in the sense of Adam at the dawn of paradise naming the animals…

La victoire avant tout sera

De blen voir ou loin

De iout voir

De près

Et que ioul ait UH nom nouveau

Apollinaire seemed to have a real feeling for the twentieth century, its marvels and disasters, both the clutter of the cities and factories and the panoply of new ideas and inventions; a feeling which somehow got all mixed up with his personal life—his love life, especially. He was still a young man when he died, in his late thirties, and must have known that his own imminent and baleful end awaited him at the front. One senses through his lines—and long before the poems he was to write under fire in the trenches at Nimes—the aura of epitaphs or premonitions of early death or the drains of expiation. His own actual dealth was of course as mysterious and “mythical” as any in his work, occurring on the eve of the Armistice, the crowds below his window shouting “Mort a Guillaumal“—meaning Death to the Kaiser.

He played the fool among Braque and Pleasso and Cocteau, but was the fragle clown of his epoch. His life was touched by the idiosyncratic, the ill-starred, the miraculous: the “theft” of the Mona Lisn; his incarceration at La Sanio prison; his pornography; his campaign on behalf of the “new art” or the “new spilt”: his advertisement of himself as the child of his century, as vagabond and bastard: the periodic temptation to the Catholicism of his youth (“si je m’ecoutais je me ferais pretre ou religieux“); the flotsam of his love life and the jetsam of his erotica (was it not Apollinaire who once said that a man is always impotent with the woman he loves?): the pictorial poems in Calligrammes (a poem about rain in the typographical shape of falling raindrops) or the famous absence of punctuation initiated in Alcools; poems that celebrate the marriage of a friend or n Rhenish Journey or that dazzle us with the simultaneisme of “Les fenerres.”

Despite the rough metropolitan tone that animates so much of his writings or a penchant for drudition amusante. Apollinaire became a master of the nalf style, not the wisdom of the nalf as in Blake, but that medley of sound and intage and rhythm that organizes itself around a certain artlessness of emotion, however worldly may be the experience out of which the emotion grows. One sees that at work in the prose as well. “La favorite.” and “Le Gilton,” for instance, his seabrous Petronlan roles, each chronicling the sordid fate of a rollicking young gigolo, are worldly in every sense; still in them too angelic merriment is heart, similar to what Gide calls “less miracles ingenus d’Apolindire (It has been estimated, moreover, that there are ninety Biblical references in Alcools and twenty in Calllgrammes.) While his experiments inverse all meet and dissolve under the divergent confluences of symbolism and of surrealism, whose movement he is the acknowledged father of, and whose name was his own invention (though applied by him originally to the paintings of Chagall).

Yet in his personality, if not his work, he looks back, I think to the twilight years of romanticism, to the theme of the self creating its own origins and its own laws. We can hear that theme perhaps in the arrogant voice of Gauguin. Why must I be a banker when I want to be an artist? Why must a day be painted brown when in my picture it will look much better pink? But what the generation of Gauguin recoiled from—the effects of the Industrial Revolution—Apollinaire accepted as a monster sacre, a wild beast that was to be tamed and purified by the sancury of the imagination, just as his own imagination could make Mobile and Odalveston real when he’d never set foot in America, just as America was to become particularly real for him since it stood at the forefront of the future, was the source of the universalization of commerce, just as Paris, his inevitable setting, shone as the melting pot of the arts.

Advertisement

His understanding of the future, however, seems to me vastly different from the futurist movements of his day—different from Marinetti in Italy and his overtures to the deities of the machine age and the racing car thought to be more beautiful than the Winged Victory at the Louvre, and different from Mayakovsky and Klebnilkov in Russia exploding the past and exulting in the victory of mass man. Apollinaire did not think of the future as a paean to devastation since he felt that Chartres and Montmartre were one, that the pope and the airplane were equally modern: in “Zone” it is Christ who captures the “world’s record for altitude.”

His position was both more delicate and ocumenical closor indeed to the later notion of Pound: “It is dawn at Jerusalem while midnight hovers above the Pillars of Hercules. All ages are contemporaneous.” Yet different from Pound as well. For Apollinaire was not interested in the redemption of the past for present purposes as was Pound in his development of the “international style” or in his obeisance to old Cathay and the touchstones of craft. For Apollinaire the “new spirit.” the “Fullness of being,” the hectic pomphlcteering done in the cause of cubism, even his hierarchical defense of les paroles qui forment et dejont l’Univers—these land to be concerned with the liberation of both the past and the present in the name of the future.

Je juge cette longue querelle de la

tradition et de l’invention

De l’Ordre et de l’Aventure

He was a visionary always in close touch with the earthy, a charioteer whose horses were “squadrons of bellowing buses,” an innovator who would proclaim the traditional—that is, the old language of the heart—a necessity. (The poet of the more distant past he most clearly echoes is of course Villon,) His programmes for change came out of the melancholy and sprightliness of his being, out of the fortuitousness of his circumstances and his polyglot ancestry (a French poet who was half-Italian and half-Polish), out of his failed loves and indestructible yearnings. He wanted to be at the frontier, and discovered in himself all the indecisions and inevitability of History—History which became for him a memento moil, that bright adventure in which he already saw himself advancing into the past, Et to recules aussi duns la vie lentement.

All who follow in his wake—Desnos, Reverdy, Eluard, Aragon—do not satisfy as completely, do not possess his special poignance: the spirit of bonheur and the wanderer’s shadow Falling across it. J’irals m’illuminant au milieu d’ombres. He had a sense of living on borrowed time, yet felt himself to be the herald of all that was to come. The stanza in “La jolle’ rousse” that begins: “Nous ne sommes pas vos ennemis“—surely that is one of the most beautiful and fateful farewells in the whole of French literature.

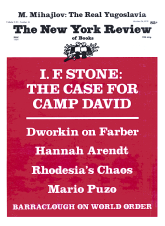

This Issue

October 26, 1978