Women’s situation, Charlotte Brontë wrote, involves “evils—deep-rooted in the foundation of the social system—which no efforts of ours can touch: of which we cannot complain; of which it is advisable not too often to think.” Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s closely argued interpretation of nineteenth-century women’s writing is concerned to show that, even in writers such as Brontë who were openly concerned with the “woman question,” pent-up frustration over the evils of which it was best not to think produced images of rage and violence: vicious doubles of submissive heroines, saboteurs of conventional stereotypes, coded messages between innocuous lines. Mad Mrs. Rochester, creeping from the attic to tear and burn, stands for them all.

Though ultimately, I believe, Gilbert and Gubar belittle their women subjects by ignoring their generosity and detachment, by representing them—as they particularly wished not to be—as women before writers, and by imposing a twentieth-century gloss on nineteenth-century imaginations, they have an important subject to explore. They are equipped (if one accepts the bias produced by ignoring male writers and most male critics) with a scholarly knowledge of the period, including its obscure corners—Frankenstein, Aurora Leigh. Maria Edgeworth, Jane Austen’s juvenilia—and they ingeniously bring in myth and fairy tale to support their arguments.

Lilith, Snow White, Beth March; the angel in the house, Salome, Swift’s sullied Celia; the Blessed Damozel, Medusa, Cinderella; Amelia Sedley and Becky Sharp; the witch and the nun, stepmother and fairy princess, mermaid and Virgin Mary; as women are the first gratifiers and punishers in all our lives, so they reappear in the imagination for ever after in opposed images of goodness and badness. In the nineteenth century the split reached its most grotesque proportions: the spotless Victorian lady, in London, lived in a city of 6,000 brothels. Thackeray’s repellent image, quoted by Gilbert and Gubar, condenses the angel and the monster into one:

In describing this siren, singing and smiling, coaxing and cajoling, the author, with modest pride, asks his readers all around, has he once forgotten the laws of politeness, and showed the monster’s hideous tail above water? No! Those who like may peep down under waves that are pretty transparent, and see it writhing and twirling, diabolically hideous and slimy, flapping amongst bones, or curling around corpses; but above the water line, I ask, has not everything been proper, agreeable, and decorous…?

Gilbert and Gubar argue that women’s conception of themselves as writers has been deeply overshadowed by this ambivalence, by the lack of an appropriate model, and the threat of monstrous unwomanliness; if, with a part of themselves, women writers endorsed the ideal of woman as modest and self-abnegating (and I think they did so more often than the twentieth century or Gilbert and Gubar imagine), it was in conflict with the part that, just by writing, defied the unforgettable reply of the Poet Laureate Robert Southey to Charlotte Brontë: “Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life, and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure will she have for it, even as an accomplishment and a recreation.” The options open, in their writing, therefore, ranged from violence to irony and from deliberate to unconscious. Brontë was an honest woman, but what are we to make of her reply to Southey?

I had not ventured to hope for such a reply; so considerate in its tone, so noble in its spirit…. You kindly allow me to write poetry for its own sake, provided I leave undone nothing which I ought to do…. In the evenings, I confess, I do think, but I never trouble any one else with my thoughts. I carefully avoid any appearance of pre-occupation and eccentricity, which might lead those I live amongst to suspect the nature of my pursuits…. I trust I shall never more feel ambitious to see my name in print; if the wish should rise I’ll look at Southey’s letter, and suppress it.

Southey commended her “receiving admonition” so “considerately and kindly.” We must, I think, make the imaginative leap necessary to see the letter, as Mrs. Gaskell did, as written quite without irony (though fortunately soon disregarded). The position of Victorian females not only had moral nourishment in it but great histrionic appeal.

But the lilies festered. Gilbert and Gubar, quoting Emily Dickinson’s “infection in the sentence breeds,” postulate a tradition of anxiety and confusion passed down to women writers, and link it with “the vapours,” with anorexic, wasting heroines, with Emily Dickinson’s agoraphobia, and above all with claustrophobia, recurrent images of women trapped in stuffy parlors, gothic mansions, isolated attics. Certainly the world that their interpretation re-creates is a suffocating one, without humor or light or mutuality, and breeding a thousand ugly and distorted forms of female rage; if not violent, as in the Brontës’ books, then cunningly subversive as in Jane Austen’s.

Advertisement

But is it the world of women’s novels themselves? Often, comparing Gilbert and Gubar’s interpretations with the texts, one finds nineteenth-century attitudes insensitively forced into twentieth-century molds. They feel very free to decide when their authors do and do not mean what they say; when the latter endorse, for instance, conventional virtues, married love, or religious faith, they assume them to be consciously or unconsciously falsifying; where they conform to twentieth-century assumptions they find them honest. This is a dangerous practice, as we know from psychoanalytical literary criticism; here it reduces rather than enhances the dignity of the writers discussed. Where Gilbert and Gubar find pessimism and rancor one often finds, on the page, an actual relish for the otherness of masculinity, a fair-mindedness about the relations between the sexes. Because these writers lived closer to the imagination than to rational argument they often did fuse the “angelic passivity” / “Satanic revenge” dichotomy. “I am so glad,” wrote George Eliot, “there are thousands of good people in the world who have very decided opinions and are fond of working hard to enforce them—I like to feel and think everything and do nothing, a pool of the ‘deep contemplative’ kind.”

But they should, we now feel, have been as embattled and anxious as Gilbert and Gubar find them. If they were not always so, can we be misreading the context? Perhaps we are unable to imagine how, in an age with fewer illusions than ours about controlling nature, submission to inscrutable Providence was everyone’s rationalization; women’s task, certainly, but they knew it as part of a joint endeavor in which they were a significant part of the pattern. “Our wills are ours, to make them thine”; every period provides its formula to keep despair in check. Or are we perhaps prevented from seeing child-bearing, and its relation to women’s status, through the eyes of previous centuries? Gilbert and Gubar, in the context of Wuthering Heights, talk of women’s “horror of being…reduced to a tool of the life process”—a recently invented horror; and it is new, too, to have to see birth as a kind of selfish environmental pollution like dropping beer cans. There may have been, in the days of high infant mortality, a deeper implicit respect for the “tools of the life process” than we can now imagine.

In any case, when these fictions go beyond sex hostility it is because, simply, the stronger the imaginative power, the wider and more objective the sympathy; Gilbert and Gubar’s critique works better with minor novels than with major ones. The authors refer back often, for instance, to the dark shadow of Paradise Lost—to Virginia Woolf’s criticism in her journals of its “aloofness and impersonality,” to Dorothea Casaubon as amanuensis to Miltonic father / husband, to Shirley Keeldar’s “His brain was right; how was his heart?”—and interpret some of the novels’ plots as female reworkings of the Genesis myth; this is perhaps ingenious in the case of Frankenstein, but Wuthering Heights’ satanic tension seems to belong to a different, self-sufficient world. Villette is indeed a novel of despair, in which submission is almost parodied, as concentration-camp inmates took over the behavior of their guards. We feel Lucy Snowe’s very calm to be poisonous with anger—though it is worth noticing that in her bitter essay on “Human Justice” (not “Human Nature” as Gilbert and Gubar say) Lucy represents justice not as masculine but as a cruel slatternly woman, like the wet-nurses Victorian babies depended on, or the mother who deserted Brontë so early. Gilbert and Gubar are also acute about the more florid fantasies of Jane Eyre; but they maltreat Shirley. They pinpoint ambivalence and masochism in The Mill on the Floss, but fail with Middlemarch.

An obvious instance is their view of the marriage of Tertius and Rosamond Lydgate in that book. Eliot sets this unhappy partnership beside the equally incongruous one of Dorothea and Edward Casaubon; both Dorothea and Tertius are shown to have embarked on these disasters through a combination of idealism and foolishness, and both must suffer for their choice and be schooled in generosity toward their partners. Dorothea does, as Gilbert and Gubar show, experience Casaubon in images of coldness and sterility, and chafe desperately against a “nightmare of a life in which every energy was arrested by dread.” But Eliot equally shows Lydgate’s suffering, hurt and ignored by a wife unable to love: beautiful Rosamond is as enclosed, as frozen as the aging Casaubon. Like him, she is both timid and self-satisfied, entirely engrossed in her own interests; Lydgate is an appendage, not a person, to her, just as Dorothea is only a convenience for Casaubon. Like Casaubon, Rosamond is incapable of an original thought; she finds Lydgate’s doctoring “not a nice profession, dear,” and is made anxious and stubborn by the discovery that he has any ideas that differ from hers.

Advertisement

This is the conventional reading, and Eliot makes it absolutely plain. No one is blamed but, simply, we like the generous, energetic, straightforward Dorothea and Tertius better than their stunted partners. It is a balanced enough picture of the difficulty, for everyone, of seeing clearly and acting generously. Gilbert and Gubar’s reading of both the women as victims, both the husbands as oppressors, simply denies the sympathy and subtlety of the book.

What Eliot makes clear is that Dorothea and Lydgate are strong characters who painfully learn—learning being the point for characters in nineteenth-century fiction—some compassion for their weaker partners. Rosamond learns salutary lessons too, but it is her husband who pays for his mistake of rashly hoping for a compliant angel, for the rest of his life: “Lydgate had accepted his narrowed lot with sad resignation. He had chosen this fragile creature, and had taken the burthen of her life upon his arms. He must walk as he could, carrying that burthen pitifully.” Casaubon, equally, is a fragile creature for whom Dorothea has to recognize responsibility. When she struggles with her rage and overcomes it with mercy, she is rewarded by seeing plainly his loneliness and timid affection, and feels “something like the thankfulness that might well up in us if we had narrowly escaped hurting a lamed creature.” To call, as Gilbert and Gubar do, this choice of hers “repression” (which is an unconscious defense, not a moral decision) is to make nonsense of what George Eliot has made so clear.

Shirley, too, is at times mutilated by one-sided interpretations. “Brontë’s heroines are so circumscribed by their gender that they cannot act at all,” say the authors, but in fact the action, both for the two “heroines” and two “heroes,” is to find a workable solution to the problem of women and men coexisting affectionately; an evenhanded combat is played out by opponents who enjoy each other. Shirley and Caroline are benign female doubles, the one softer than she likes to appear, the other tougher. Caroline’s odious uncle—“These women are incomprehensible”—represents the view that good relations between the sexes are impossible. All marriages, at bottom, are unhappy, all husbands and wives “yoke-fellows,” fellow-sufferers.” But “If two people like each other, why shouldn’t they consent to live together?” asks Caroline; and she and Shirley thrash the question out, distinguish good and bad behavior from sex roles:

“We know that this man has been a kind son, that he is a kind brother: will any one dare to tell me that he will not be a kind husband?”

“My uncle would affirm it unhesitatingly. ‘He will be sick of you in a month,’ he would say.”

“Mrs. Pryor would seriously intimate the same.”

“Miss Yorke and Miss Mann would darkly suggest ditto.”

But—

“When they are good, they are the lords of the creation…. Indisputably, a great, good, handsome man is the first of created things.”

“Above us?”

“I would scorn to contend for empire with him,—I would scorn it. Shall my left hand dispute for precedence with my right?—shall my heart quarrel with my pulse?—shall my veins be jealous of the blood which fills them?”

Before the marriages at the end, all four characters have learned lessons: Robert has been chastened, Caroline fortified, Louis—the poor tutor, male equivalent of Jane Eyre—learned to put love before pride and property, and “Captain” Shirley tamed, in a delightfully erotic game of submission to her tutor (who is in turn supported by her: “I thought I should have to support her and it is she who has made me strong”). The two women clear-sightedly like their chosen men—“I do like his face—I do like his aspect—I do like him so much! Better than any of these shuffling curates, for instance—better than anybody: bonnie Robert!” and the regard is mutual—“It delights my eye to look on her: she suits me….” The four have struggled with the problem that the sexes must have differences in order to attract each other, and come up with excellent compromises. The remarkable thing is that there is honesty, not repression; amicable erotic teasing, not festering hostility; and the marriages at the end, far from being “unreal,” “ridiculous fantasy,” and “a fairy tale,” as Gilbert and Gubar assert, have been well worked for.

Gilbert and Gubar, with Brontë’s use of stone as an image of masculine lovelessness in mind, see the setting of Robert’s proposal—by a stone wall and fragment of a cross—as a deliberate suggestion of the barrenness of marriage. But, as with other images they interpret throughout the book, there is a different meaning that they ignore: in Yorkshire the outcropping stone seems the very image of strength and constancy, and Charlotte Brontë uses it in this sense, not only in Rochester’s “brow of rock” and Louis’s “great sand-buried stone head” but in the tremendous metaphor in her preface to Wuthering Heights—“a granite block on a solitary moor…there it stands colossal, dark, and frowning, half-statue, half-rock….” The very use of “Moore” as the brothers’ surname is a use of the Brontës’ central image of timeless and austere sustenance.

Shirley’s vision of the true Eve which she opposes to Milton’s is of “a woman-Titan…. She reclines her bosom on the ridge of Stilbro’ Moor; her mighty hands are joined beneath it. So kneeling, face to face she speaks with God.” The male and female images coalesce. Gilbert and Gubar’s aim is also to reconstruct an Eve, a mother-artist “whom patriarchal poetics dismembered.” Indeed they do open up a new dimension in these works, and one will always see them differently. But “we must dissect in order to murder” the fetid angel in the house, they say, and their Eve is not re-created without further dismemberment.

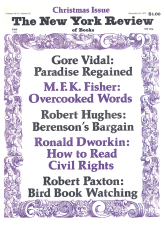

This Issue

December 20, 1979