In response to:

The Conscientious Spy from the November 19, 1987 issue

To the Editors:

Not content with the rambling and uninformative polemic that passed for a review of my book Klaus Fuchs, Atom Spy [NYR, November 19, 1987], Stephen Toulmin now ascribes to it a “lighthearted manner” in which I allegedly “equated the whole antifascist movement of the Thirties with that part of it which the Russians undoubtedly controlled…tarring all the liberal and social democratic opponents of Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco with the same brush as their Communist allies” [NYR, March 17].

On the contrary, it is Mr. Toulmin who is carrying tar and brush these days. These are all his words, not mine, a bizarre caricature of what were measured, qualified, and brief comments on the context of the 1930s out of which Klaus Fuchs emerged. Fuchs was drawn to the KPD because it seemed to offer the best chance of resisting Hitler, in Germany before 1933 and in England after Fuchs fled there on party orders. I in no way ever equated communist, liberal, and socialist opponents of Hitler in the 1930s.

Mr. Toulmin is a sometime Cambridge philosopher uninformed about the history of atomic espionage who apparently knew both Fuchs and Allen Turing personally and who utilized my new book to grind his old axes. The readers of The New York Review will be far better served by reading the book themselves.

Robert C. Williams

Vice President for Academic Affairs

Dean of the Faculty

Davidson College

Davidson, North Carolina

Stephen Toulmin replies:

I am happy for people to read Dean Williams’s life of Klaus Fuchs and judge for themselves if his account of Fuchs’s espionage, from 1941 on, is as objective as he thinks; or if (as I argued) it is slanted by the same assumptions as his account of European politics before World War II.

He may not have meant to “[equate] communist, liberal, and socialist opponents of Hitler.” Still, his book depicts, e.g., the Popular Front, the Oxford Union “King and Country” debate, and the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War (all cited in my review) in terms used at the time only by right-wingers who saw liberal and socialist anti-Nazis as so many “dupes of Moscow,” and continued—right up to September 1939—to treat protests at Fascist or Nazi brutalities as distracting attention from the more urgent task of opposing Soviet Communism.

Instead of grumbling at me for ax grinding, Dean Williams might do better to reread his book, and consider why his perspective on Europe in the 1930s appears so out of kilter to readers who grew up there during the Hitler years, and still feel the tides of its politics on their pulses.

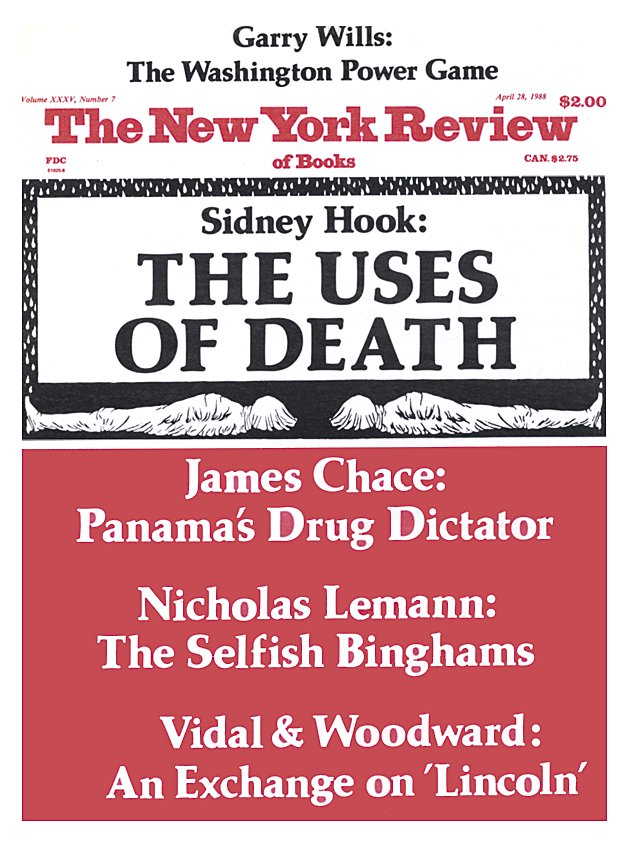

This Issue

April 28, 1988