For twenty-five years the history of modern Germany, as presented in our standard historical works, has been molded by the assumptions and preoccupations of liberal historiography. I have already discussed the preoccupation with Nazism, which is one of the more obvious characteristics of these studies.1 But there are other, more fundamental ways in which liberal assumptions have colored the interpretation of modern German history. If I return to the question, therefore, it is not to plough over old ground but to consider the adequacy itself of the liberal interpretation. The point at issue, of course, is not the substantive contribution of a generation of historians to the history of Germany between 1870 and 1945, but the postulates and tacit presuppositions with which they worked.

What are the basic characteristics of the liberal view of German history? For present purposes they can be reduced to three. The first, deeply embedded in the philosophy of German idealism, is the primary role of ideas in history and, therefore, by implication, of the makers of ideas, a belief that history is shaped by ideas rather than social relations and the interplay of economic interests. The second is a deep-seated elitist bias, an unspoken but unquestioning assumption that the so-called cultural and political elite is the element in any society that determines the course of events, and that the historian’s main task is to discuss their thoughts, attitudes, decisions, and actions. Finally, and on a different level, there is an implicit endorsement of the German national state as it emerged in 1871, seen as the fulfillment of the liberal struggle in 1848 and 1849 for German unification. Bismarck’s Reich becomes, as it were, a standard by which German history, before and after, is measured and judged.

If we wish to see how the writing of modern German history has been affected by these assumptions, we cannot do better than turn to Hajo Holborn’s History of Modern Germany, for Holborn’s book, as I indicated in my previous article, is the most judicious and authoritative epitome of a generation of liberal scholarship. Holborn’s liberal assumptions, it is only fair to add, are tempered, far more than in the case of lesser historians, by a robust awareness of social and economic factors; but a residuary liberal Weltanschauung is there nevertheless, subtly influencing the structure and balance of his work. It accounts for his allocation of space—well over a page to the Ems Telegram, forty lines to Haeckel, only eighteen lines to Marx—and for the structure of his book, which mirrors unquestioningly the central place assigned to Bismarck’s Reich in German liberal historiography.

For Holborn, liberalism and nationalism (the title of his first section) led inexorably to the founding of the new Reich in 1871: it was “consolidated” by Bismarck between 1871 and 1890, and the book ends with its destruction by Hitler in 1945. These are the familiar divisions of liberal historiography, the conventional political framework, neatly packeted by reigns, ministries, and wars; the question, of course, is whether they are adequate.

Holborn’s liberal assumptions color his view of German history in other ways. It is scarcely accidental, for example, that he chose an article by Theodor Eschenburg on “the role of personality in the crisis of the Weimar republic” to open the volume of essays he put together shortly before his death. Characteristic, again, is the meticulous attention Holborn pays to the detail of foreign policy, particularly Bismarck’s foreign policy, surely an implicit underwriting of the old German belief that war and diplomacy and the genius of statesmen are the determinative factors in a people’s history.

And finally, his liberal bias is manifest in his warning against exaggerating the role of “social conflict” in the rise of Nazism (can it, one asks oneself, possibly be exaggerated?) and his insistence that the real trouble stemmed from a “decline of German education.” This, as Ringer’s Decline of the German Mandarins2 attests, is a fashionable theme among liberal historians; but need it be said that it is an unproven (and, to my way of thinking, implausible) hypothesis? According to David Childs, to whose admirable little book we shall shortly come, educational “standards did rise,” if somewhat patchily, during the Weimar period, and (as one who underwent the experience) I know of no reason to believe they were worse, either in schools or universities, in 1930 than they were in 1890.

In the long term, however, the most significant indication of the limitations of Holborn’s conceptual framework is his implicit but unquestioning acceptance of the myth of Bismarck’s Germany. Good historian as he was, he knew better than most how many chance factors combined to bring about Bismarck’s solution of the German question in 1871, how much the outcome depended on Bismarck’s own peculiar qualities, how precarious and fragile the structure of the new Reich was. But, faithful to the old liberal tradition, with its search, ever since 1813, for a national German state, he makes this Reich his yardstick. If he stops dead in 1945, the reason, as I have said, is that 1945 saw the destruction of its unity. The “brief history” of Germany after 1945, he tells us, “cannot be treated as a mere projection of the history of earlier epochs.” And the reason? “The chasm created by the disaster of 1945,” “the loss of one quarter of the territories belonging to the Germany of 1937,” “the division of Germany into two separate political and social entities.”

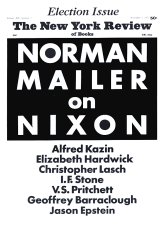

Advertisement

These statements reveal so much that it is worth taking a second look at them. The “brief history,” to begin with: but the history of Germany after 1945 is twice as long as the history of the Third Reich to which Holborn devotes more than 100 pages, and longer than the history of the Weimar Republic, which gets 179. The boundaries of 1937: but what is so sacrosanct about the boundaries of 1937, which most Germans in 1937 thought of as a temporary limitation imposed by hated conquerors? The division of Germany: but a divided Germany was nothing new, rather it was a return to the situation of 1870 which Bismarck had destroyed, not a break with the past but a reversion to a past much older and longer than Bismarck’s Reich. And, finally, “the disaster of 1945”: disaster for whom? Certainly not for Americans, still less for the peoples of Europe suffering under Nazi rule. But was it really a disaster for the Germans to be liberated (as they so quickly claimed they were pining to be) from Nazi tyranny?

It will be said that I am making mountains out of molehills. I think not. For the liberal ideology, like all other ideologies, inevitably produces blind spots that stand in the way of historical understanding. Consider, as one last example, Holborn’s characterization of Goebbels as an “offensive guttersnipe.” I should not, admittedly, particularly have liked to have had Goebbels as a member of my seminar, but he was, after all, a graduate of Heidelberg University, and the German universities in 1921—as anyone can discover by reading the excellent first chapter of Mr. Ringer’s book—were not renowned for opening their doors to guttersnipes. David Childs, as it happens, describes Goebbels as “intellectually very able,” and though his description and Holborn’s are not, perhaps, mutually incompatible, the difference is interesting.

But the only point I wish to make at the moment is that Holborn evidently found it difficult, in a book otherwise marked by almost excessive sobriety of judgment, to apply the same standards of scholarly objectivity to the Nazis as he does to the other obnoxious characters—Bismarck, for example—who stalk through his pages. Certainly his distaste for Goebbels is humanly understandable, but it is another question whether superciliousness and disdain are the best approach to the Nazi phenomenon. Liberal assumptions, the unspoken prejudices of the Bildungsbürgertum, may be an obstacle to understanding; and the suggestion I am making, with all respect, is that they are.

What if the liberal interpretation of German history, which has dominated for a quarter of a century, is itself wrong? Or what if, to put it less crudely, while it may reveal some part of the truth (which no one, I imagine, would seriously deny), it reveals less than the whole truth and perhaps obscures some aspects altogether? Or what, at least, if it sets the whole story in a false perspective?

Holborn’s decision to end his book in 1945 is not really much different from arguing that the fall of the “Corsican” in 1815—for contemporaries every bit as much an ogre as the “Bohemian corporal”—marked so complete a break in French history that the years after 1815 cannot (in Holborn’s phrase) “be treated as a mere projection of the history of earlier epochs.” In fact, of course, no one has suggested that they can; but this did not prevent historians, with the passage of time, from raising the question of continuity and discontinuity in France before and after 1815 and finding a place for Napoleon in the longer perspective of French history. Is it not time, after twenty-five years, for a similar re-appraisal of German history? The point, of course, is not to exculpate the Nazis or dismiss Nazism as a temporary aberration—which it was not—but to find a vantage point for a better understanding of German history.

I ask these questions with the more assurance because it is evident that I am not alone in questioning the adequacy, in the 1970s, of the liberal interpretation of German history. No doubt the majority of historians still plods along, as the majority always does, in the old way; but there are heartening signs, mainly among the younger generation, that something at last is moving, and it is significant that the change is visible in all the major centers, in Germany itself, in France, in England, and in the United States.

Advertisement

In Germany the new generation includes Helmut Böhme, whose study of the underlying economic trends of the age of Bismarck is one of the very few postwar books on German history that really breaks new ground.3 On a different level it includes Martin Broszat, the present director of the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich, whose book Hitler’s State may be regarded as the postliberal counterpart to Bracher’s liberal interpretation in The German Dictatorship.4 It also includes some of the younger historians grouped around Broszat, a selection of whose work is contained in the useful volume of essays compiled by Holborn shortly before his death. 5

In England there is David Childs, whose little book on Germany since 1918 refreshingly avoids the opportunities for platitudes and mediocrity which the writing of an introductory survey presents.6 Paradoxically, the old preoccupations are most tenacious in the United States. But here also change is in the air. David Schoenbaum was one of the first, in the introduction to his book Hitler’s Social Revolution,7 which appeared in 1966, to voice the growing doubts about the validity of the standard historical approach. More recently Harold J. Gordon has criticized intellectual historians who credit their class with “more influence than it can legitimately claim” and “try to fit the National Socialists into shoes which they feel should fit them” instead of placing themselves in the shoes of the National Socialists.8

When we look at this reaction more closely, what becomes immediately evident is that it stems from the alliance between historians and social scientists, which is one of the most hopeful developments in history today. Gordon uses the techniques of group analysis; Childs is by profession a political scientist. The same is true of Karl Dietrich Bracher and Alfred Grosser, both members of the “middle generation” which stands midway between Holborn’s old-fashioned liberalism and the new perspectives of the younger generation.9 Finally, in the United States, there is Fritz Stern, whose self-proclaimed intention, in the thoughtful, sensitive essays he has recently published, is to break away from the “conventions and abstractions,” including the “conventional divisions of historical enquiry,” which clutter our minds and distort our view of the German past.10

We need only list the names of these scholars to see that we are not dealing with self-proclaimed iconoclasts, itching to tear down the old liberal idols; not even with the sort of self-consciously radical “revisionists” who are causing such tremors among the worthy members of the American Historical Association. The search of these scholars for new ways is still tentative and exploratory; but when their contributions are added together, they amount to a very different—and, I would say, far more authentic—view of the German past than that to which we have become accustomed.

The first feature that distinguishes the new school from the old is its refusal to draw a line across the ledger of German history in 1945. Grosser’s book is, of course, primarily important because it provides essential material for a history of Germany which spans the prewar and the postwar years. But one of its striking features is his unceasing concern with the question of continuity and discontinuity, and his refutation of “the notion of 1945 as an absolute zero.” No one, to the best of my knowledge, has attempted to write a coherent history of Germany from 1871 to 1971, or from 1866 to the accession of Willi Brandt in 1969; but Grosser’s pioneering work now makes this possible, and with the appearance of David Childs’s short history we have at least a scholarly account which covers half the period. In view of how much he has to cram into a short space, Childs has picked his way with originality and intelligence. Anyone daunted by the length and density of the works of Holborn, Bracher, and Grosser may turn to him with every confidence; in some respects, particularly in the discussion of the German Democratic Republic, his account is as fair and balanced as anything we have.

The changes that come from lengthening our sights—from viewing the century that began in 1871 as a whole, instead of cutting it up into separate self-contained packets—are more considerable than may appear at first glance. The first and most important is that Nazism appears in a different setting. As Fritz Stern points out, if we wish “to gain a proper perspective” it is necessary to “examine German history not at points of obvious divergence or extremity, such as Nazi Germany, but in periods of apparent normality and quietude.” And Grosser puts his finger on one of the main differences between the younger and the older generations when he questions the long-standing tradition of treating Germany as “a country set apart by the inexorable fatality of its history,” particularly by “the chain of events which led to Adolf Hitler.” This is a rejection, politely expressed, of the tradition which underlies both Holborn’s and Bracher’s books.

What is needed, and what the longer perspective available today makes possible, is a view of German history which neither magnifies nor minimizes the Nazi experience. This is probably the main virtue of David Childs’s book. Childs neither brushes aside the Third Reich as an unfortunate aberration nor elevates it into a central theme. He does not allow us to forget that, down to 1930, “Hitler was not making much impact on the masses.” He finds space (which Holborn does not) for statistics showing that “many more Germans than we gave credit for opposed the Nazis” and that “the unknown German worker” was “more typical of the German resistance than the officers of the July Plot.” What he shows, in other words, is that, if there was a chain of events which led to Hitler, there was also a chain of events which did not, and that—as Grosser points out—institutions such as the churches and the Social Democratic Party, “despite their checkered history,” can “point to a continuous evolution” that spans the Nazi period and links the years before 1933 with the years after 1945.

The question of continuity and discontinuity is, of course, extremely complex, and the only point I wish to make is that the suggestion that 1945 created a “chasm” in German history is a misleading simplification. When Holborn tells us, with characteristic pathos, that the defeat of Hitler “made it possible for the Germans to recover their roots in their national past,” the one thing that is certain is that this is what they did not do. Here at least there was no continuity.

On the other hand, Grosser is surely right in speaking, at least in regard to the three western zones, of “a definite continuity of social organization and social values.” But here again continuity was of different kinds, and if some threads lead back before 1933, there was also notoriously more continuity between the Third Reich and what came after than it is sometimes convenient to acknowledge. As Childs points out, General Heinrici, the commander of the German army opposing the Russians in the final stage of the war, “lived to tell, in peaceful retirement, of the last days of Berlin,” and “Goering’s and Hess’ families spent the postwar years in comfortable obscurity in West Germany.”

When a coherent, continuous account of the last century of German history comes to be written (as assuredly it will) the question of continuity and discontinuity before and after 1945 will play an important part, and it will be necessary to consider the Nazi years not only as a breach of continuity—which, in some respects, they were—but also as a stage on the road from the Germany of Bismarck to the Germany of Brandt. This is something liberal historians, revolted by the excesses of Nazism, have been reluctant to do. “It is essential,” Bracher insists, “that we recognize that nothing basically new was evolving.” In reality, as Broszat and Dahrendorf have made plain, a good deal that was new was evolving, even if it was due not to deliberate Nazi policy so much as to the shattering impact of the Nazi regime on the existing German social structure.

Predictably liberal historians have reacted with a good deal of hostility to the suggestion that the Nazis helped—even if blindly and unintentionally—to shape the structure of postwar Germany, and when David Schoenbaum published his book with the title Hitler’s Social Revolution he was promptly rapped over the knuckles, in these pages as elsewhere.11 But Dahrendorf is surely right in his contention that National Socialism, by undermining and sometimes decimating the old elites, “removed the social basis for future authoritarian governments along traditional German lines” and so “abolished the German past” in a way the Weimar Republic had totally failed to do. 12

Subsequent events—wartime destruction wartime evacuation, and postwar expulsions—certainly contributed to make the change irrevocable. But it was the Nazis who set it off, and it is a fair criticism of liberal historiography that it has evaded the question. That is why Richard Grunberger’s large volume is disappointing, in spite of occasional flashes of insight.13 There was room for a serious large-scale social history of Nazi Germany, but instead of systematic social analysis Grunberger prefers to entertain us with a welter of spicy and malicious anecdotes. Nevertheless he also concedes that Hitler “did drag Germany, half-heartedly kicking and screaming, into the century of the common man,” and that, beneath a “penumbra of social demagoguery edged with farce,” the Third Reich instigated “developments toward greater social equality, or at least upward mobility.” During the six peacetime years of the Nazi regime, Grunberger notes, “upward mobility was double that of the last six years of Weimar.” This may be an unpalatable fact for liberals to swallow, but it is too important to be shirked.

In the longer perspective of German history (I am not speaking of European history or international history, which is quite another thing) it is possible that the social revolution the Nazis set in motion will appear as the most enduring legacy, perhaps the only enduring legacy, of the Third Reich. If, as Mr. Ringer says, the present generation of “German intellectuals have adjusted to the mass and machine age” and “mandarin culture has become a distant memory,” the changes brought about by twelve years of Nazi rule are one, if not the only, reason. We cannot just dismiss them as a relapse into savagery; and anyhow even a relapse into savagery may have positive results. No one judges the French Revolution simply by the Terror and the tricoteuses sitting and crowing beside the guillotine; and sooner or later historians will have to take a corresponding attitude to the German revolution—for that, as Dahrendorf has said, is what National Socialism really was.

All this implies a change of attitude towards National Socialism which is the second great difference between the liberal and the postliberal historians. It is best seen in Broszat’s meticulous analysis of the structure of the Third Reich, but I shall try to illustrate it, as briefly as possible, by reference to Gordon’s book on the Hitler Putsch of 1923 and to some of the essays by younger German historians in the volume edited by Holborn.14

There are two main aspects. First, the Nazi terror and the SS state, treated for so long as evils fit only for moral condemnation, are now being subjected to cool factual analysis which, because of its scrupulous authenticity, is far more damning than emotional denunciation. Secondly, whereas liberal historians were more interested in the roots of Nazism and how it came about—with the paradoxical result, as Carl Schorske has pointed out, that they paid more attention to the Weimar Republic, as the alleged seedbed of Nazism, than to the Third Reich itself15—the younger generation is concerned with what Nazism was, with seeing how it actually operated after 1933, and with analyzing its essential elements in depth. They do not underestimate Hitler’s ideas and plans, but for them the essential point is to establish what happened when the time came to apply those ideas in practice. This is the difference Bracher has in mind when he writes that “contrary to general opinion, January 30 was rather a beginning than an end.”

Stated baldly, this seems so obvious a fact that to insist on it may seem unnecessary. The reason is the psychological blockage liberal historians experience when confronted by anything as alien to their mentality as Nazism. How otherwise shall we account, for example, for their reluctance to discard the view that the notorious Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933, was a deep-laid Nazi plot? Fritz Tobias showed as conclusively as will ever be possible that this was not the case;16 but his evidence accorded so badly with the traditional picture of the Nazis as unscrupulous, unprincipled villains that it left the majority of liberal historians (including Bracher) incredulous and resentful. For them, as Hans Mommsen says, the Reichstag fire was “a prize example of the terrorist methods employed by the National Socialists to take their opponents by surprise,” and they were psychologically unwilling to accept the possibility that an incident which so clearly helped the Nazis to cement their rule can have been anything but the result of a carefully drawn up plan.

In reality, Mommsen shows in his essay, the facts tell a different story. Unscrupulous and evil Hitler and his lieutenants may have been, but the arrests that followed the fire and the manipulation of the elections six days later were “not the outcome of clear and purposive decisions” but of “spontaneous, unconsidered reactions.”

This is not merely a conflict over the interpretation of facts; rather it reveals two basically different attitudes toward National Socialism. Historians of the older generation approach the problem from a moral and ideological point of view. In asserting that the Nazis deliberately planned the Reichstag fire, they are proceeding not from an objective examination of the historical record but from a preconceived notion of the Nazis as evil terrorists who would stop at nothing to get their way. For the younger generation, on the other hand, what is significant is the speed and vigor with which the Nazis reacted to a crisis which took them totally unawares; for we have only to contrast these qualities with the hesitancy and flabbiness of the other German parties—with what Julius Leber called “the whole inner weakness and indecision of the Weimar front”—to see how important a factor they were in carrying the Nazis from their original insecurity as expendable allies of the army and big business to a position of total domination.

If Mommsen’s analysis of the Reichstag fire forces us to revise our view of the Nazis in 1933, Harold Gordon’s new book undertakes a similar, even more far-reaching revision of their position ten years earlier, at the time of Hitler’s famous beer-hall Putsch in 1923. The conventional picture of the beer-hall Putsch, as presented once again in Richard Hanser’s racy, popular account, is of a “milestone” on Hitler’s “road to power,” and though minor characters abound, Hitler and his stormtroopers occupy the center of the stage.17 Gordon’s achievement is to dissect this conventional picture step by step and show how deceptive it is.

Even Bracher maintained that Hitler had arrived, in 1923, “at the point at which he decided to set out on the road to power.” Nothing of the sort, Gordon replies. In reality, Hitler acted precipitately, unreflectingly, desperately, convinced that otherwise his followers would desert him and his movement would collapse. But that is not all. The reason the Putsch failed, Bracher argues, is because the various dissident groups were “badly co-ordinated.” This implies an over-all plan, but in reality there was no plan. The different groups, Gordon shows, were not so much “badly co-ordinated” as “at loggerheads.” The largest paramilitary organization in Bavaria had no intention of following Hitler; the most redoubtable of all the free corps leaders, Ehrhardt, stood ostentatiously aside. Far from being the leading figure, Hitler did not “dominate even the left wing, let alone the entire movement,” and nothing could be more misleading than “to look back on Bavaria in 1923 and see only the NSDAP.”

Three points of general significance for the history of National Socialism emerge from Gordon’s study. The first is the futility of the “standard” moralistic approach, which lays down that “the National Socialists were bad and did bad things because they were bad,” an approach (as Gordon says) that “does not help the serious historian” who wants to know “why and how they got into a position” to do these things. The second is the “largely mythical” character of the “old, conspiratorial school of historical interpretation,” which depicts Hitler and his associates as consummate schemers, “sitting down and coldly planning a putsch in a situation that left them free to decide their best possible course of action,” when in reality they were driven by events to embark on an ill-considered, ill-prepared and extraordinarily incompetently conducted operation which never had one chance in a hundred of success.

But perhaps the most important point is the way our preoccupation with National Socialism has distorted our view of German history. Where others have trained the limelight on Hitler and the Nazis, Gordon places them in historical perspective, and the result is that the beer-hall Putsch, instead of figuring as the inauguration of a carefully planned campaign leading step by step to 1933, is firmly set in its time, not the prelude to the Nazi revolution but the last—and by no means the most dangerous—of a series of attempts to overthrow the established order that had punctuated the troubled history of the Weimar Republic ever since 1919.

The results of this revision are a picture of Nazi reality far more differentiated and flexible than we have come to accept. Where the older generation demonized the Nazis, building them up into criminals of almost superhuman dimensions, the cumulative effect of the work of the younger generation is to de-demonize them. Broszat, in particular, has shown how little substance there is in the conventional interpretation of Nazi policy as the systematic implementation of long-term objectives laid down—in Mein Kampf or elsewhere—long before the seizure of power. The old picture of the Nazi state as “a perfect monolithic order” crumbles when confronted by the facts. Instead of a carefully planned and organized instrument of totalitarian domination, what we see is an almost haphazard tangle of overlapping and conflicting authorities, brutal and oppressive but also clumsy, wasteful, and inefficient.

Nor is it true—as Bracher, among others, has suggested—that this confusion was deliberately created by Hitler as part of a policy of “divide and rule,” designed to make his own position unassailable. On the contrary, it simply grew up piecemeal, as a result of weak control, indecision, and inertia. Even on questions of art and culture there was no considered policy when Hitler came to power. Nothing is less true, as Hildegard Brenner has shown, than Holborn’s statement that “Goebbels managed to subject the totality of publicly expressed opinions and cultural creations to his orders” in a few months during the summer and fall of 1933. In reality, the battle over modern art went on (that “guttersnipe” Goebbels supporting the modernists) throughout 1933 and was only decided—against Goebbels—in September, 1934.

The episode is not so unimportant as it may seem, for it underlines the point made by Bracher and Hermann Mau that the Nazis, far from exercising planned dictatorial powers from the moment Hitler became chancellor in January, 1933, only finally consolidated their position after August, 1934. Indeed, if the “institutional basis” of Nazism, as Bracher rightly maintains, was the SS and the Gestapo, it might be more correct to put the turning point in June, 1936, when Himmler was finally vested with dictatorial powers.

The revision of the conventional picture of the Nazi seizure of power has wider implications than may at first seem evident. No one in his senses today minds very much either way about the precise process by which the Nazis established control, and it is easy to lose patience with these painstaking studies of the detail of Nazi policy. But this is not the point. The point is rather that no realistic view of the last century of German history is possible until the myths surrounding the history of Nazism have been dismantled. It is in this wider perspective that the work of the younger historians should be seen. The last thing they intend is to exculpate the Nazis; but they realize that we can never hope to see German history in perspective until they have been cut down to size.

The corollary to the “de-demonization” of National Socialism is the “de-demonization” of Hitler. I confess it is a subject that leaves me cold, not so much because it is difficult to challenge current preconceptions about Hitler without appearing to whitewash him, but because it smacks too much of that preoccupation with personalities that seems to me to be one of the blemishes of liberal historiography. But it is probably true that here also there is room for new thought, and two recent books at least make a start. One is Schramm’s diagnosis of Hitler’s personality as revealed in his table talk in 1941 and 1942;18 the other is Eberhard Jäckel’s analysis of his political ideas as expressed in Mein Kampf and the so-called “secret” book of 1928.19 Neither seems to me entirely satisfactory, if only because they leave out the central period of Hitler’s life. Between the third-rate provincial politician of 1928, with no apparent future, and the apparently irresistible conqueror of 1941 lie the years of astounding success between 1930 and 1940, and it is hard to think that they contributed nothing to his development.

Schramm’s book is, in effect, a reaction against the two stereotypes which have governed so much of the literature on Hitler: trivialization and demonization. Neither the familiar caricature of a psychotic, semi-educated, petty bourgeois agitator, nor the picture painted by historians such as Meinecke and Ritter of a “demonic character,” totally outside the norms of ordinary human experience, does justice to the baffling complexity of Hitler’s personality. Schramm’s essential point is that we shall never get within measurable distance of the problems Hitler poses if we dismiss him simply as a “terrible amoralist” or a “hyper-Machiavellian no longer inhibited by law.” In reality, Hitler had his own “well-grounded and consistent” morality and his own “concept of legality,” and the fact that we may find them repulsive is no reason not to take them seriously.

This conclusion, which Schramm arrives at after a slow beginning, is the starting point of Jäckel’s book. A member of the younger generation, Jäckel has fewer inhibitions than Schramm and pursues his analysis more systematically, but for him also the first step is to realize that Hitler “had principles”—“not moral ones in the usual sense…but…principles nevertheless”—and since it was in accordance with these principles that “his policies took their course,” we shall not get very far until we have subjected them to dispassionate analysis.

As Jäckel points out, the current image of Hitler is confused and inconsistent, and blurred by subjective moral judgments. Even Bullock, in his well-known biography, describes Hitler as “an opportunist entirely without principle,” and then, almost in the same breath, speaks of the “consistency and astonishing power of will” with which he pursued his aims. On one side we are told that Hitler had no ideas, let alone a consistent Weltanschauung, on the other that everything he did was clearly set out in Mein Kampf. According to Rauschning, even Hitler’s anti-Semitism was tactical; his only principle was power and domination for its own sake. At the same time we are bidden to believe that the aims which confront us during the war were formulated by 1924 and were pursued from that time forward with unswerving resolution.

Jäckel’s critique of the self-contradictions historical research has brought upon itself by abandoning systematic analysis and relying instead on intuitive judgments and the obiter dicta of ex-Nazis such as Hermann Rauschning is cogent and convincing. So also is his analysis of the development of Hitler’s ideas from the “conventional foundations” with which he began in 1920. At the age of thirty, as Jäckel says, Hitler was still “a conventional anti-Semite and a conventional revisionist,” mouthing commonplaces which had been the claptrap of right-wing German politicians for a generation. Even his idea of conquering living space in the east was taken over lock, stock, and barrel from the pan-Germanists of the First World War. Countless other right-wing agitators had denounced the Jews, the Bolsheviks, and the Versailles settlement. Hitler’s distinctive quality was his ability to take these separate threads and weave them together into a single, self-consistent Weltanschauung. Separately, they were neither new nor original; but by combining them in a logically integrated ideological structure, he galvanized them into a powerful instrument of political action.

Jäckel is right to insist (contrary to the myth propagated by Hitler himself) how comparatively late Hitler’s distinctive intellectual development began, but when he goes on to suggest that it was completed in all important respects, including the idea of the extermination of European Jewry, by 1928, if not earlier, the evidence he brings forward is less convincing. Moreover, two newly discovered interviews, which Edouard Calic has recently published, point in the opposite direction.20 The importance of these interviews, which Hitler granted to Richard Breiting, the editor of the leading conservative Leipzig daily newspaper, in 1931, lies in the light they throw upon his ideas at the crucial moment in his career after the elections of 1930 had made him for the first time a serious force in German politics. It would be surprising if his astonishing success at the polls had not boosted Hitler’s self-confidence and encouraged him to push his ideas to new extremes; and in fact, as Calic points out, the interviews unfold “plans for the future which could not have been deduced either from his speeches or from his book Mein Kampf or from the Nazi party’s program.”

And yet even at this date his views on a matter so fundamental as anti-Semitism were far from completely developed. Historians have assumed without question that the “final solution” was, in Calic’s words, “the culmination of a long-prepared program…announced in Mein Kampf.” In reality, it appears that Hitler’s ideas only gradually crystallized after long gestation, perhaps not finally before 1938. To begin with, there is no doubt, as Jäckel shows, that the solution he foresaw for “the Jewish question” was emigration or deportation. The question, of course, is when this attitude changed. Jäckel believes that it was in 1924, during Hitler’s imprisonment in Landsberg, but the evidence he adduces is tenuous and inconclusive. It is also contradicted by the Breiting interviews. Hitler, in fact, told Breiting quite categorically that he did not “intend to massacre the Jews,” and though Breiting came away convinced that Hitler’s “tirades of hate against the Jews were no mere intimidation maneuver” and that he would persecute them if he came to power, he had no doubt that persecution, even at this late date, meant at worst expropriation and expulsion.

I am well aware that anyone who questions the view that the “final solution” was in Hitler’s mind from the start of his political career is asking for trouble; it may also be said that it does not matter in the long run—and certainly made no difference to the victims—whether the road to the “final solution” was longer and less direct than has commonly been assumed. The points I wish to make are different. The first is that Jäckel is surely right in insisting that we cannot pick and choose among Hitler’s statements, rejecting those (for example, his statement to Breiting in 1931 that he did not intend to kill off the Jews) that do not conform to our presuppositions and accepting only those which tally with our preconceived ideas. The second is that it is all too easy to write as though anti-Semitism was rampant in Weimar Germany and all Hitler had to do to win support was to play upon it. In reality, the weight of the evidence indicates that anti-Semitism was a liability rather than an asset in the Nazi program, but a liability that had to be accepted in deference to Hitler’s ingrained prejudices.

No one doubts that an undercurrent of anti-Semitism was always present in Weimar Germany, welling up at times of economic distress—after 1918 and again after 1929—and subsiding when conditions improved. But, as Donald Niewyk has pointed out, it was an “irritant” rather than a major problem, and no one took Nazi anti-Semitism “very seriously” until long after 1933.21 The danger of exaggerating its importance in the light of after events—like the danger of exaggerating the importance of the Putsch of 1923—is the distortion of German history which results. The Weimar Republic, as David Felix has truly said, “was much more than an antechamber to the Nazi period,”22 but that is how it appears when we make the search for the antecedents of Nazism our measure and criterion. That is why it is important to analyze such bitterly sensitive issues as anti-Semitism coolly and objectively.

The question that arises is whether these partial revisions of current orthodoxy add up to a new view of recent German history. My answer is that they do, but only if they are seen in a broader setting. If I have been concerned in the main with various aspects of National Socialist history, it is not because I think they are the most important but because this is the area dealt with by most of the books I have reviewed. In reality, the interpretation of National Socialism is only one area in which the traditional liberal approach to German history is under attack, and though it is obviously impossible on this occasion to consider other areas—for example, the events of 1918 and 1919—it is important to emphasize that what is at issue is not our view of particular aspects of Nazi history but rather the adequacy of the liberal interpretation and its underlying assumptions. It is because the younger generation of historians has cast doubt on their validity that a new view of German history, unencumbered by liberal presuppositions, has become so necessary. Recent research has altered our picture not merely of particular incidents and phases but of the whole course of German history from Bismarck to the present day. In a concluding article I shall try to draw the threads together and pick out at least the broad contours of the new pattern.

(This is the second of three articles.)

This Issue

November 2, 1972

-

1

“Mandarins and Nazis,” NYR, October 19. ↩

-

2

Fritz K. Ringer, The Decline of the German Mandarins: The German Academic Community, 1890-1933 (Harvard, 1972). ↩

-

3

Helmut Böhme, Deutschlands Weg zur Grossmacht (Kiepenheuer & Witsch: Cologne, 1966). ↩

-

4

Martin Broszat, Der Staat Hitlers (Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag: Munich, 1969); The German Dictatorship by Karl Dietrich Bracher (Praeger, 1970). ↩

-

5

Republic to Reich: The Making of the Nazi Revolution. ↩

-

6

Germany Since 1918. ↩

-

7

Hitler’s Social Revolution: Class and Status in Nazi Germany, 1933-1939 (Doubleday). ↩

-

8

Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch. ↩

-

9

Bracher, The German Dictatorship; Germany in Our Times by Alfred Grosser. ↩

-

10

The Failure of Illiberalism by Fritz Stern (Knopf, 1972). ↩

-

11

Heinz Lubasz, “Hitler’s Welfare State,” NYR, December 19, 1968. ↩

-

12

Society and Democracy in Germany, by Ralf Dahrendorf (Doubleday, 1967). ↩

-

13

The Twelve-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi Germany, 1933-1945. ↩

-

14

I shall refer specifically (and without any intended reflection upon the value of other contributions) to the following essays: Hans Mommsen, “The Reichstag Fire and its Political Consequences”; Hildegard Brenner, “Art in the Political Power Struggle of 1933 and 1934”; Hans Buchheim, “The Position of the SS in the Third Reich”; K. D. Bracher, “Stages of Totalitarian Integration”; and Hermann Mau, “The Second Revolution.” ↩

-

15

Carl E. Schorske, “Weimar and the Intellectuals,” NYR, May 7, 1970. ↩

-

16

The Reichstag Fire, by Fritz Tobias (Putnam’s, 1964). ↩

-

17

Putsch! How Hitler Made Revolution by Richard Hanser (Wyden, 1970). ↩

-

18

Hitler: The Man and the Military Leader, by Percy Ernst Schramm (Quadrangle, 1971). ↩

-

19

Hitler’s Weltanschauung. ↩

-

20

Secret Conversations with Hitler. ↩

-

21

Socialist, Anti-Semite, and Jew: German Social Democracy Confronts the Problem of Anti-Semitism, 1918-1933 by Donald L. Niewyk (Louisiana State U.P., 1971). ↩

-

22

Walther Rathenau and the Weimar Republic: The Politics of Reparations by David Felix (Johns Hopkins, 1971). ↩