Thanks to television, people comparatively obscure during their lifetimes enjoy the possibility of becoming celebrated after they are dead. Indeed, they may do better than that—they may achieve what amounts to a substantial measure of immortality, which is to say that as long as TV tapes of them exist and as long as an audience can be found of a size sufficient to make it worthwhile to broadcast the tapes, they can go on occupying a prominent place in the world for many decades and perhaps even—who knows?—for centuries.

Of course I am thinking of a particular case: that of my friend Joseph Campbell, who taught at Sarah Lawrence College for almost forty years, his subject being the role of myth in human history. He wrote a number of books on this and related topics, the best known of them in his lifetime being The Hero with a Thousand Faces and The Masks of God. He retired from Sarah Lawrence in 1972 and was at work on still another book when, in 1987, at the age of eighty-two, he died after what his obituary in The New York Times described simply as “a brief illness.” That brevity was, so his friends thought, characteristic of him: he died within a few months, and in doing so he displayed what many of his friends took to be a characteristic—and enviable—alacrity.

I call Campbell’s alacrity enviable because, in our present state of medical ignorance, the disease that was killing him wasn’t to be outwitted except in a negative sense by the degree to which its duration could be reduced: Why dawdle in the presence of the inevitable? At the same time, however, for Campbell to have consented to be sick at all seemed an impermissible aberration. Ordinarily, it isn’t a reason for astonishment when an old man is called upon to die, but Campbell had seemed to us never to grow old. If by the calendar he had reached his eighties, in person he was a good twenty years younger than that, or so any stranger would have assumed on meeting him. He was slender and quick-moving and because of his erect carriage gave the impression of being taller than he was. He had thick dark wavy hair, bright blue eyes, unwrinkled skin, and a pink complexion. He laughed readily, boyishly, and his laughter remained especially attractive in old age because, as far as one could tell, his teeth were his own, neither false nor capped. He was, in short, an invincibly youthful figure, so uncannily unaltered by time that I used to accuse him, to his delight, of practicing some hitherto unknown form of satanism.

We would encounter each other, Campbell and I, at monthly meetings of the Century Club, in New York City. Handsome in black tie, he would be standing near one or another of the bars that were set up on such occasions in the art gallery off the landing of our grand marble stairway. Unlike many scholars, he was convivial and at ease meeting strangers; moreover, having enjoyed a cocktail or two before dinner, he participated with relish in the give-and-take of vigorous discussion, which is (or is reputed to be) one of the most welcome features of the Century.

To the bewilderment of many members of the club, myself included, Campbell’s lifelong study of conflicting points of view in a variety of world cultures had not resulted in his accepting a variety of conflicting points of view in his own culture. Scholar that he was, surely he could be counted on to observe with a scholar’s detachment the desire for upward mobility of minority peoples in the United States? Surely he would be the first among us to understand and forgive if sometimes they displayed crude and even dangerous patterns of behavior? Well, nothing of the kind! So far was Campbell from applying the wisdom of the ages to the social, political, and sexual turbulence that he found himself increasingly surrounded by that he might have been a member of the Republican party somewhere well to the right of William F. Buckley. He embodied a paradox that I was never able to resolve in his lifetime and that I have been striving to resolve ever since: the savant as reactionary.

It was also a paradox that, although Campbell had devoted most of his teaching career to Sarah Lawrence—and a brilliant teacher he was—he never approved of the nature of the college, which was liberal if not radical in respect to politics and permissive in respect to personal conduct. He came from a middle-class Irish-Catholic background, which in his generation implied a certain Jansenist puritanism, and when he sought to describe the extent to which he believed himself to have escaped it—that is, to have successfully paganized himself—his words tended to grow at once lofty and mushy: he would suddenly be spouting language as coyly imprecise as that of any sentimental Victorian novelist. In respect to marriage, for example, Campbell would say that in undertaking it “we reconstruct”—Campbell’s words—“the image of the incarnate God.” Whatever that curious statement may mean, it certainly implies that marriage is an ambitious project and that we must therefore take care in choosing the correct marriage partner. How is this to be accomplished? According to Campbell, “Your heart tells you.”

Advertisement

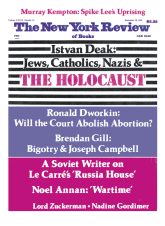

Campbell’s bigotry had another distressing aspect, which was a seemingly ineradicable anti-Semitism. By the time I came to know him, he had learned to conceal its grosser manifestations, but there can be no doubt that it existed and that it tainted not only the man himself but the quality of his scholarship. For example, he despised Freud, and it appeared from our talks that he did so in large part because of the fact that Freud was Jewish. He approved highly of Jung and not least because Jung wasn’t Jewish. In an episode unknown to me until after Campbell’s death, as a young man he had provoked an indignant letter from no less a person than Thomas Mann, one of his two literary idols (the other was Joyce). In December 1941, three days after Pearl Harbor, Campbell gave a lecture at Sarah Lawrence on the subject “Permanent Human Values,” urging the assembled undergraduates not to be caught up in war hysteria and not to be tricked into missing the education to which they were entitled simply because “a Mr. Hitler collides with a Mr. Churchill.” Campbell argued that “creative writers, painters, sculptors, and musicians” ought to remain “devoted to the disciplines of pure art.” In time of war, the fortitude of the literary man and artist consists of remaining aloof from the political cockpit, giving no thought to the “undoing of an enemy.” At that very moment, Mann was devoting much of his energy to arousing the world to the menace of Hitler and the Nazis; for reasons difficult to imagine, Campbell sent a copy of his lecture to Thomas Mann, then living in Princeton, and received a civil but obviously angry letter in reply, which, translated from the German, reads in part:

As an American, you must be able to judge better than I, in a country which just now, slowly, slowly, under difficult and mighty obstacles, I hope not too late, has come to the true recognition of the political situation and its necessities, whether it is appropriate at this particular moment to recommend political indifference to American youth….

It is strange, you are a friend of my books, which therefore according to your opinion must have something to do with “Permanent Human Values.” Now these books are forbidden in Germany and in all countries that Germany rules, and whoever reads them or even should sell them, and whoever would so much as praise my name publicly would be put into a concentration camp and his teeth would be bashed in and his kidneys split in two. You teach that we must not get upset about that, we must rather take care of the maintenance of permanent human values. Once again, this is strange.

Campbell’s speech did him no lasting harm; it was not widely circulated and it seems likely that it was dismissed by those who read it as the special pleading of a passionate young humanist, and with the eventual British-American victory over the Nazis (for Mr. Hitler did indeed collide with Mr. Churchill) even Mann may have found it in his heart to forgive him. Nevertheless, Mann’s rebuke evidently galled Campbell. Many years later, he gave a talk in which he claimed that a monumental mistake had been made when Mann was invited to give the main address at the banquet held in 1936 to celebrate Freud’s eightieth birthday. According to Campbell, in the course of his eulogy of Freud, Mann had criticized Freud—whom Campbell mistakenly believed to have been in the audience and whom he described as “that poor little old man”—for not being aware that most of his discoveries had already been made by earlier German writers. (In fact, Mann’s admiration for Freud was unbounded and Freud was much gratified by the eulogy.) Campbell wound up his speech by noting that Mann “had lost altitude” as an artist by descending into political activity and raising his voice against the Nazis.

During Campbell’s long career at Sarah Lawrence, his was a name well known in academic circles. In the narrower circle of admirers of James Joyce, he was revered as the coauthor, with Henry Morton Robinson, of a learned and amusing book called A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake. It was from this book that, according to Campbell, Thornton Wilder had pinched much of the material for his play The Skin of Our Teeth. (Campbell may have had some justification in his accusation: Wilder was a notorious literary magpie.) It wasn’t, however, until the series of TV interviews he recorded with Bill Moyers was first put on the air almost a year after his death that the quiet eminence he had enjoyed in life suddenly leapt into posthumous fame.

Advertisement

These programs, six in number and lasting an hour apiece, were edited from some twenty-four hours of filmed conversation between Campbell and Moyers, carried on during late 1985 and early 1986. The series was entitled The Power of Myth, and a book was later published under the same title, drawing on both the broadcasts and on transcripts of the unedited conversations. The book became an instant best seller, as did a new edition of The Hero with a Thousand Faces. By then, the program had attracted an audience far larger than anyone had expected. It was a hit, and probably in reruns and on cassette it will go on being a hit for a long time to come.

Moreover, it was plain that the show’s popularity wasn’t simply a result of the awed praise of TV critics or even of the almost universal respect in which Moyers has come to be held; among the kind of people who watch so-called head shows on public television, Moyers has assumed a mantle not unlike that possessed on commercial television in a somewhat earlier period by Walter Cronkite, who was often described as “the most trusted man in America.” No doubt Moyers himself would be the first to affirm that it was Campbell’s personality, to say nothing of his message, that millions of people were reacting to and, it appeared, were heartily agreeing with.

As he had done as a teacher at Sarah Lawrence, Campbell was performing brilliantly before a class—this time, one that consisted not of a handful of young women but of an audience beyond counting, of mixed gender and of nobody knew what range of ages. As interrogator, Moyers was playing with his usual sincerity the role of brightest-boy-in-the-class. His questions were always simple but never to the point of being simple-minded; reassuringly, they reflected a formidable degree of knowledge of the subject, which is to say that they took care to avoid that tiresome journalistic device, a pretense of ignorance as a means of securing information. Moyers had plenty of information, gained in part from a close reading of Campbell’s books, and he showed an eagerness to be instructed in the means by which that information could be made to yield wisdom.

What, then, was Campbell’s message? And why was it so astonishingly well received? Some of his listeners assumed that the message was a wholesomely liberal one. In their view, he was encouraging his listeners not to accept without examination and not to follow without challenge the precepts of any particular religious sect, or political party, or identifiable portion of our secular culture. By taking these precautions, his listeners would escape the conventional, unconscious blinders that all societies are likely to wear. That was the gospel Campbell had preached exactly forty years earlier, in the preface to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, where he wrote:

There are of course differences between the numerous mythologies and religions of mankind, but this is a book about the similarities; and once these are understood the differences will be found to be much less great than is popularly (and politically) supposed. My hope is that a comparative elucidation may contribute to the perhaps not-quite-desperate cause of those forces that are working in the present world for unification, not in the name of some ecclesiastical or political empire, but in the sense of human mutual understanding. As we are told in the Vedas: “Truth is one, the sages speak of it by many names.”

Campbell’s hero indeed had a thousand faces, which meant that he was equally authentic, equally to be admired, in whatever guise he might be seen to emerge. He was Christ, he was Buddha, he was Abraham Lincoln, he was John Lennon, he was whomever you chose as model for the nature of your own life, suffering, death, and (with luck) rebirth.

Superficially, this was indeed the message, or one of the messages, that The Power of Myth conveyed. In that case why was it greeted so enthusiastically by millions of TV watchers? For surely most, Americans were not eager to hear that their fears and longings were comparable to those of billions of other human beings, most of them illiterate, impoverished, and diseased, who lay scattered willy-nilly over the face of the globe; still less were they eager to hear that life itself ended in suffering and death, with (but also perhaps without) an eventual rebirth.

What I detect concealed within this superficial message and ready to strike like one of the serpents that are such conspicuous inhabitants of the Campbell mythology is another message, narrower and less speculative than the first. And it is this covert message that most of his listeners may have been responding to, in part because of its irresistible simplicity. For the message consists of but three innocent-sounding words, and few among us, not taking thought, would be inclined to disagree with them. The words are “Follow your bliss,” and Campbell makes clear the consequences of doing so:

If you follow your bliss, you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living. Wherever you are—if you are following your bliss, you are enjoying that refreshment, that life within you, all the time.

Now, it is hard to imagine advice more succinct and, at first glance, more welcome. Seek to do whatever it is that makes you happy, Campbell tells us, and you will find fulfillment, you will have achieved union with the ineffable, you will be one with whatever form of god-head strikes your fancy. Eros will be there and so will agape; you will frolic in these and other delectable attributes as a dolphin frolics in the wine-dark sea, and if it happens that you are an ugly frog, sooner than you may expect you will be kissed by a virtuous maiden and become a handsome prince. In the world of mythic make-believe, out of which Campbell derived his three-word precept, the miraculous is a gratifying commonplace.

At one point in their conversations, apparently seeking to pin down the relationship between miraculous myths and attainable bliss, Moyers asks, “What do myths tell me about happiness?” Campbell responds:

The way to find out about happiness is to keep your mind on those moments when you feel most happy…. What is it that makes you happy? Stay with it, no matter what people tell you. This is what I call “following your bliss.”

Moyers finds Campbell’s circular, repetitive answer unsatisfactory and presses on: “But how does mythology tell you about what makes you happy?” Campbell replies:

It won’t tell you what makes you happy, but it will tell you what happens when you begin to follow your happiness, what the obstacles are that you’re going to run into.

He then recounts several American Indian tales about maidens rejecting inappropriate suitors, and after the last of these tales Moyers gamely inquires:

Would you tell this to your students as an illustration of how, if they follow their bliss…if they do what they want to, the adventure is its own reward?

Campbell says,

The adventure is its own reward—but it’s necessarily dangerous, having both negative and positive possibilities, all of them beyond control.

Plainly, to follow one’s bliss is advice less simple and less idealistic than it sounds. Under close scrutiny it may prove distasteful instead of welcome. For what is this condition of bliss, as Campbell has defined it? If it is only to do whatever makes one happy, then it sanctions selfishness on a colossal scale—a scale that has become deplorably familiar to us in the Reagan and post-Reagan years. It is a selfishness that is the unspoken (the studiously unrecognized?) rationale of that contemporary army of Wall Street yuppies, of junk-bond dealers, of takeover lawyers who have come to be among the most conspicuous members of our society. Have they not all been following their bliss? But what of the fashion in which they have been doing so—is it not radically at odds with the Judeo-Christian traditions that have served as the centuries-old foundation of our society?

The precept to follow one’s bliss is bound to interfere sooner or later with another precept that many Americans were brought up to believe and continue to believe, to wit, that we are our brother’s keeper. And when that moment of interference arrives, what are we to do? If he were alive, what would my old friend Joe Campbell’s advice to us be under such circumstances? No doubt he would begin by suggesting, with a gentle, rueful smile, that we had totally misconstrued the meaning he had assigned to bliss. But—we would protest—had he not said that bliss consisted of our doing whatever made us happy, and was it not possible for our happiness to spring from an unbroken series of self-aggrandizing acts? Upon which Campbell, smiling more ruefully than ever, might say that we had also misconstrued what he had meant by happiness.

We would then protest that in fact we had done no such thing. For in other passages of his conversations with Moyers Campbell had stated that what we perceive as good and evil are but two faces of a single entity, which is life itself, unchanging and unchangeable. (“The world,” he assures Moyers, “is great just the way it is. And you are not going to fix it up. Nobody has ever made it any better.”) From which it can be argued that selfishness and unselfishness, like good and evil, though contradictory in appearance are identical in nature, and may therefore serve equally well as a source of happiness.

Insouciantly permitting, every concept to contain its opposite, Campbell expands on his recommendation that we follow our bliss by a further recommendation to the effect that we turn inward rather than outward in our pursuit of self-fulfillment. And again his words have, upon our first hearing them, the ring of a spiritual rather than a material enhancement, for surely Nirvana is inward and the ignoble vexations of this world are outward. But again we had better take a long look at the possible consequences of choosing item A over item B: Is it not perhaps only another way of elevating selfishness over unselfishness, of reiterating in a disguised form that we need have nothing to do with our brothers?

By now I have made plain why, in my view, the Campbell-Moyers conversations gained such unexpectedly high TV ratings and why Campbell’s books have found themselves—and continue to find themselves—on any number of best-seller lists. It appears that Campbell’s message is one that the most Americans are eager to hear. Far from being spiritual, it is intensely materialistic; in a form prettied up with abstractions—bliss, happiness, godhead, ground of being, and the like—my old spellbinding friend is preaching a doctrine similar to that which Ayn Rand voiced in her novel, The Fountainhead. Over four million copies of that work have been sold since it was published in 1943. Throughout its many pages, Rand tirelessly reiterates the gospel of individualism as a political and ethical ideal and denounces altruism in its practical applications—any species of philanthropy, whether private or public—as a demeaning weakness, unworthy of mankind.

The hero of The Fountainhead, Howard Roark, is widely assumed to be based on Frank Lloyd Wright, who, like Rand, was consummately elitist in spirit. As a friend of Wright’s, I was well aware that he talked a great deal about democracy, as his lieber meister, Louis Sullivan, had often done before him, but the word meant whatever those two cranky amateur philosophers wished it to mean, and in neither case did it imply respect for the masses. Wright wrote sneeringly of the common herd in his book on Sullivan, which he called Genius and the Mobocracy, and some of the words in that book might well have been lifted directly from the speeches that Rand put into the mouth of Howard Roark and that Campbell uttered in his conversations with Moyers. “The creator lives for his work,” says Roark.

He needs no other men. His primary goal is within himself…. The man who attempts to live for others is…a parasite in motive and makes parasites of those he serves.

Two years before The Fountainhead was published, young Campbell was saying at Sarah Lawrence,

The artist—insofar as he is an artist—looks at the world dispassionately: without thought of defending his ego or his friends, without thought of undoing an enemy; troubled neither with desire nor with loathing.

Had all of Campbell’s experience over a long lifetime led to this, then—the continued championing of a right-wing antihumanitarianism that he and Ayn Rand and their like had first proposed back in the Forties? And if it is this doctrine that lies behind the exceptional success of the Campbell-Moyers conversations, then that success has for me the dead taste of the ashes of the Reagan years, in which so many notions of social justice, incorporated into law over the past half-century, have come under attack and in many cases have been reduced to impotence. I perceive that in my years of poking fun at Campbell over what I called his antediluvian political views, I had been far too easy on him and on myself. I had not striven hard enough to unravel the paradox that he embodied: the savant as reactionary. Listening to Campbell and Moyers, I was appalled to realize that what I had regarded as mere eccentricity in the private back-and-forth of conversation in a club was something altogether different when it took the form of a conversation on TV—when by giving one a national platform and making one famous (in Campbell’s case, famous after he was dead), TV had succeeded in transforming my seemingly harmless companion into a dangerous mischief-maker. Which is to say, and with sadness, that my friend had become my enemy.

This Issue

September 28, 1989