In response to:

Roman Grand Guignol from the January 18, 1990 issue

To the Editors:

In his interesting review of P.F. Widdows’s Lucan, Hugh Lloyd-Jones repeats the common knowledge that “English hexameter is very unlike the Latin hexameter, being based on stress accent-rather than on quantity.”

than on quantity.”

As a musicologist I am hardly competent to discuss anything other than the empty sounds of either ancient or modern poetry, and yet I am always surprised to read this about English verse. Composers have long known that it is false, and anyone who doubts that might try the following experiment.

I suggest reading out loud twice the following lines from Widdows’s translation (quoted in the review) spoken by Cato:

ALL this I KNOW, and I NEED NO

REINFORCEment from HAMMON.

MEN ARE BOUND to the GODS, and,

with ALL THEIR ORacles SILENT,

NOthing we DO IS DONE WITHOUT

their diRECtion…

First read in what might be called an “accentual” manner, taking care that each syllable has exactly the same duration, but giving a strong stress accent to the syllables printed in capitals. Then read in a “metrical” manner, speaking in a monotone without any stresses but giving the marked syllables twice the length of the others.

To be sure, neither way of reading is either musical or poetic. But I think that the latter way may be somewhat closer to a good speaker’s declamation of this type of verse—English or Latin. Indeed, while I cannot comment on the faithfulness of Widdows’s English to the sense of Lucan’s Latin, the flexible yet regular rhythm of the translation (when read metrically) seems to me to function remarkably like that of epic hexameter—for example, in the way in which successive longs underline the meaning of and give the requisite rhetorical stress to the word “reinforcement.”

Unfortunately none of this would be evident to a reader—or even perhaps a poet—lacking some familiarity with ancient meters. But it is pleasing to see at least one translator who has faith in the music as well as the sense of ancient poetry.

David Schulenberg

University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Hugh Lloyd-Jones replies:

Mr. Schulenberg makes a good point. The words are so arranged that their natural spoken stress regularly falls within the ideally regular alternate stress which the prevailing rhythm of the verse leads the ear to expect. This is called “metrical ictus”; but quantitative verse, such as the ancient Greeks and Romans wrote, depends on quantity, the measurement of syllables which are in themselves long or short, and so is very different from modern verse depending on ictus and word-stress, and the pull between them.

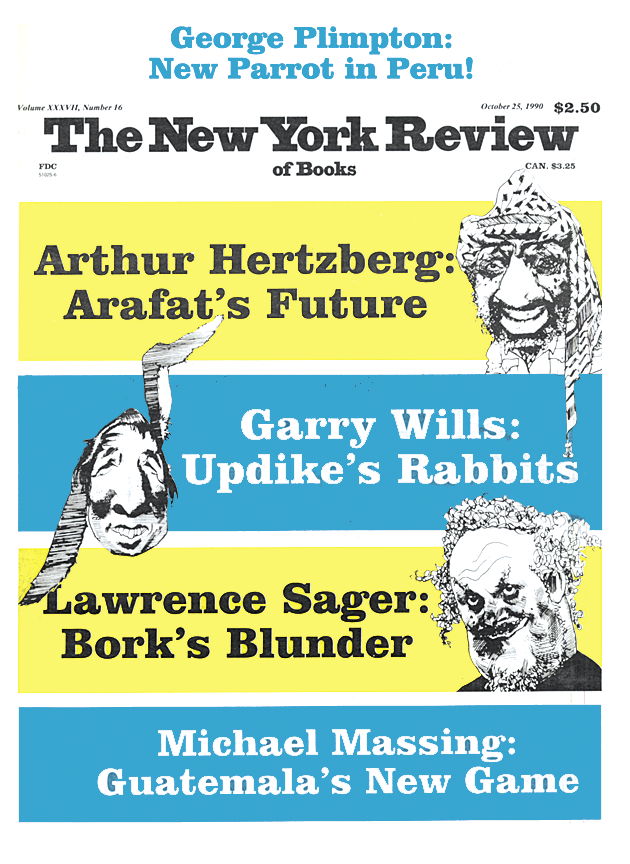

This Issue

October 25, 1990