1.

Change is neutral as a general phenomenon, and can only be assessed case by case. We sit in our unsatisfactory present, surrounded by two mythologies that exalt their respective and conflicting ends—better futures by the fancy of progress, and rosier pasts by the fable of golden good old days. Sports fans are particularly subject to the dangers of nostalgia and a falsely glorified past. Young children deify Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, or even Reggie Jackson (who flourished at the dawn of my middle age)—none of whom they have ever seen in play. But nostalgia is surely silliest in older fans who should be able to grant some strength to the former contestant in a battle between eyewitness testimony and clouds of later memory. (I should mention that “older” has a definite meaning in this particular ballpark. Rooting is generational, and you enter the category of older when you first take your child to a game.) We simply have to be tough in the face of such temptation to moon about better pasts. I confess that I am about to submit to this enticement in choosing to focus this year’s review of baseball literature on five books exalting the prime joy of my own youth—New York baseball in the late 1940s and 1950s. I must therefore begin with an apologia.

Consider the twin dangers of arguments about the good old days. First of all, we need only listen to Kindertotenlieder, Mahler’s searing songs on the death of children, or place a call to Japan by pushing a few buttons, to remind ourselves about unambiguous improvements in the quality of our present lives. Second, I see no sense in fighting to retain old pleasures that have become truly inconsistent with modern life. We may (and should) lament the deaths of friends and lovers, but we cannot hope to retain perpetual youthfulness and must accept inevitability with grace—a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant and a time to pluck up.

To choose an example involving both dangers, I see no point in decrying baseball’s current structure of high salaries, though it has spawned a host of dire consequences endlessly rehearsed in the copious literature of baseball lamentation—including the complacency and self-indulgence of some stars, and the rupture of any loyalty between player and town, as teams become holding operations for the passage of mobile and monied players who spend a year or two and then move on. (Yes, the old days were marvelous, when DiMaggio defined the Yankees for life, Williams belonged to Boston and the Red Sox, and Musial was forever a Cardinal. But remember that only a few stars used this system to their advantage, and that most players were peons performing for peanuts, prevented by the infamous reserve clause from negotiating their own contracts, and therefore held as vassals to their owners. And I need hardly remind anyone that black men couldn’t play in the big leagues at all until 1947.)

Besides, how can we deny players the benefits that modern life has produced? Broadcasting fees have vastly increased the “take” of major league teams. Either the owners keep the windfall, or it goes to the players who actually generate the money. Ball players are members of the entertainment industry and are only receiving the going rate (maybe even a bit less, if you consider rock stars) for their services. Do not, therefore, lament things that cannot be anymore, and never were so good anyway.

Let us, instead, save our complaints for preservable goods lost through stupidity, complacency, and avarice. Baseball presents a fascinating duality to students of change and tradition. Nothing substantial has altered on the playing field. We can understand Babe Ruth in 1927, or even Nap Lajoie in 1901, because they played exactly the same game, always changing its style of course (as any dynamic institution must) but operating for more than a century without any major alteration in rules or physical dimensions. (By contrast, I can make no meaningful contact with football and basketball players of my grandfather’s generation, for I do not grasp their different games, while the numbers attached to their performances permit no comparison with modern assessments.) Yet, at the same time, the commercial structure of baseball as a business, and the social status of baseball as an institution (including such basics as times and places of play), have altered almost beyond recognition.

I do not like many of these changes (while welcoming others), but I generally resist the strategy so rightly ridiculed in Ko-Ko’s proposed beheading of “the idiot who praises, with enthusiastic tone, all centuries but this, and every country but his own.” I have, instead, accepted what I didn’t like because I could see no alternative that would keep baseball consonant with changed realities in modern American life. “Museums of practice” cannot survive as mass institutions (opera, an elite institution, just barely manages). The miracle of baseball, after all, lies in the fact that on-field play still works so splendidly in its unaltered mode; how did the rulemakers of the 1890s know that they had constructed a game for the ages?

Advertisement

But baseball is now about to institute a change of a different order—erosive (if not destructive), unnecessary, and preventable; and therefore to be lamented. This change is not overtly bigger than others of recent years, but it cuts at the heart of baseball’s central joy. As I write this essay, we are witnessing baseball’s last pennant races. Next year, teams will no longer play the regular season in pursuit of a meaningful pennant—the banner of victory for first place in a daily struggle lasting from April to the end of September. They will, instead, compete for a slot in an ever-widening, ever-extending, multi-tiered series of playoff steps to the World Series. Why does this change matter so much?

The National League began in 1876, the American League (still called the “junior circuit”) a quarter century later in 1901. In 1903, the champions of the two leagues met for the first World Series (won by the Boston Red Sox). Each league contained eight teams, concentrated in the east and geographically confined by the practical limits of train travel to a region defined by Chicago, St.Louis, and Washington at the corners. In 1952, the same teams still played in the same places, under a slightly increased and stabilized schedule of 154 games (up from 135–140 in the 1903 season).

In 1953, the hapless Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee (and later to Atlanta). The even more hapless St.Louis Browns moved to Baltimore in 1954, where they have become, as the Orioles, one of baseball’s most successful teams. This trickle then expanded to a flood as old teams migrated and new clubs joined. Major league baseball moved into California, Canada, Texas, and most recently, Denver and Miami. Each league now maintains fourteen teams. (You really have to know your history to make any sense of current names. Why should seaside Los Angeles be lost to a basketball team called the Lakers? They are the transplanted Minneapolis Lakers of yore. Why should the same city, where no one walks, host a baseball team called the Dodgers to honor wary Brooklyn pedestrians?)

I do not see how any fair person can object to these expansions. After all, by what right could the northeastern segment of the United States continue to wield territorial hegemony over baseball after team travel by airplane made the entire nation accessible. Similarly, how can one lament the first alteration, initiated in 1969, of the balance between regular and postseason play—the splitting of each league into two divisions, with an added round of championship play between division leaders in each league before the World Series? Postseason play for a single club made sense in an eight-team league, but one chance in fourteen (the present number of clubs in each justifiably expanded league) seems too rarefied, while one in seven (the amended probability of victory with two divisions per league) preserves the old balance while implying a round of playoffs before the World Series. Thus very few fans deplored the added intra-league playoffs, which have become a welcome and exciting part of the baseball season. Why, then, do so many of us object so strongly to the second tier of playoffs that will start next season—not as a consequence of further expansion (and this observation holds the key to our complaints), but as an end in itself.

To epitomize the new system, each league will be further fractured into three geographical divisions (five teams in the east, five in the center, and four in the west). Four teams (the divisional leaders plus a “wild card” second-place team with the best record across the entire league) will then meet in the added round of playoffs. The winners of this elimination will then play a second round to determine participants in the World Series. Since the regular season schedule of 162 games will be maintained, and since non-domed stadiums in places like Boston and Chicago really don’t permit a beginning much before the traditional April date, the World Series will now take us nearly to November (if not literally so, given postponements for rain—or snow!).

To understand why this change is qualitative and destructive rather than merely incremental and inconsequential, we should consider the packaging of laundry detergent. In this commercial world, ordinary and regular do not exist; the smallest available package is marked “large”—and sizes then augment to super, gigantic, and colossal. Such “promotions” without substance are merely risible, but more consequential inflations in sport alter the product itself in fundamental ways, not just the packaging. The root cause of sporting inflation is entirely obvious: the financial control and consequent dictation of policy by national TV and its advertisers, by far the dominant source of modern revenue. Regular season games are regional and for small markets; postseason championship series can be advertised and promoted nationally for big bucks.

Advertisement

Basketball, football, and hockey, our other major professional team sports, have been inflated in this way for years. The so-called “regular” season has become something of a farce, with scarcely more meaning than a set of exhibition games. Few teams are eliminated from postseason championship play. The rounds of postseason competition have become so numerous that fans now speak of these endless eliminations as a “second season.”

We may grasp the structural absurdity of such a situation, but I don’t think that lamentations are in order—for football, basketball, and hockey were created (at least as professional activities with truly mass appeal) by television and constructed in its image. Their regular seasons never had a central place in American culture (much as they meant to relatively small coteries of devoted fans)—so demoting regular season play, while silly in a logical sense, has not robbed us of anything precious and formerly possessed.

But baseball’s regular season has been, for a century, a joy, and a definition of life’s patterns for millions of fans—a rhythm and a drama that buds in spring, becomes our constant companion in summer, burns most brightly for a short time when maple leaves turn red in October, and then ends when the trees become bare. Baseball is not just an occasional three hours at the ballpark. Baseball, through its many months and 162 games, is going to the corner store every morning, buying the paper and a cup of coffee, exchanging a few words with Tom the proprietor about last night’s game, and then spending ten minutes at home with the box scores. Baseball is the solace of long summer drives, when a game on the radio beats a Beethoven symphony. These are not romantic images but daily summer realities for millions of Americans.

The World Series was a bonus—a short national blast capping a long regional drama. No one disputed the priorities and balances: a separate and postclimactic World Series, following the primacy of a long regular season, filled (as all drama must be) with moments of adventure and despair, and longer stretches of boredom—and at its climax, a race for a key reward, the league pennant. This popular format, maintained until now as levels of attendance and income continued to rise, has been slain for no reason of complaint or failure—but only because the game’s moguls sniffed a source of expanded revenue in destroying baseball’s unique emphasis on a regular season. National TV has triumphed over regional loyalty and baseball has adopted the depressing model of other big-business team sports. Our regional, daily pleasures have been sacrificed to a series of staged national productions that can sell advertising for a million bucks a minute.

My complaint is not idiosyncratic or unusually intense. Many players, fans, and writers share my belief that this change differs from all others in marking a fundamental sacrifice and degradation, not a mild inevitability requiring our acquiescence or accommodation. Bobby Brown, now president of the American League, but the Yankee’s stylish third baseman in my youth (and later a distinguished cardiologist), expressed his anger and sadness in much the same terms. Michael Madden, the Boston Globe’s excellent sports columnist, wrote with feeling when baseball’s owners, meeting in Boston (of all places) on September 10, made their fateful decision—and also introduced another change symbolic of their servitude to national television:

Baseball will now have Pete Rozelle’s [football’s] wild card, and John Ziegler’s [hockey’s] expanded playoffs, and David Stern’s [backetball’s] playoff double-headers to be marketed on TV…. The circle was rounded when baseball also announced yesterday that it had moved its opener next April from the traditional Monday to Sunday and had sold off that one opener to ESPN… Did they have to do this in Boston? It should have been done in the Great Mall of America outside Minneapolis, in some big TV store, with the owners all standing in front of 100 flickering TV screens behind them, not mere steps from Boston Common.

There is another reason for singling out this change as especially significant—one that transcends the parochialism of baseball and speaks to a fundamental issue at the heart of any general discussion about the quality of life in modern America: regional differentiation vs. commercially driven standardization.

Regionalism is a wonderful thing, provided that each person has a region and that no one is thereby excluded or downgraded. I relish the fact that we New Yorkers talk funny, and that art deco skyscrapers symbolize our city. I am glad that one shot of different buildings, and one sentence from the local cop, conclusively identifies Chicago as the locale of Harrison Ford’s The Fugitive. But we must set boundaries to this love of variety. I accept the need, even the blessings, of standardization in practical matters: we require a worldwide telephone dialing system and a network of national highways; we cannot move entirely on picturesque one-lane roads passing through every village and hamlet.

We should try to conceive a set of Deuteronomy-like rules about separation: where we will allow standardization, and where we must preserve the key notions of distinctive locality, and of neighborhood. We need domains of standardization, and realms of regionalism, each in its appropriate place, and linked in mutual respect and recognition. I accept and even want McDonalds at the highway interchange—drive-thru and all—but not in my little neighborhood of ethnic restaurants, and not next to the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota.

The voluminous commentary on baseball’s last pennant races has not generally linked our loss to this key issue of regionalism and its virtues; yet, surely, the wider significance lies squarely in this vital debate. I cannot think of a more important or more pervasive example of precious and legitimate regionalism than the traditional structure of baseball’s regular season. No one is excluded; everyone has a regional team, now that baseball has expanded throughout the nation and into Canada. The traditional system works; nothing is broken. The local rivalries animate schoolyards, living rooms, and bars; teams—especially the older ones—define a major part of the soul and substance of cities and regions. Why would we surrender something so valuable?

The regular season represents regionalism; postseason play is national. The traditional balance has been just right—a long time of local sharing, followed by a short and intense national contest. Why are we about to downgrade the regional part (while perversely retaining its admirable length after eviscerating the meaning)? I want to travel on the subway to Fenway Park, argue and kibitz with my seatmates Jay, Jenny, and Jeff, follow games in the morning paper; I don’t want to spend a month in front of my TV screen watching round after round of eliminations in an ascending series labeled like laundry soap. The elimination of a meaningful pennant after a 162-game struggle, and the addition of a new round of playoffs, is like installing a Pizza Hut in my corner grocery store—and I resent it.

2.

Arguments about historical loss suffer a grave difficulty in any attempt to persuade. How can anyone know what they haven’t experienced? Why should younger fans feel an attraction for something they cannot know, especially when most social trends threaten regionalism and boost commercial standardization. Our hope can only lie in testimony from people who have experienced the pleasures of regionalism as fans and players. We can identify a key time and place for the best of a better way (though I will admit to a certain unfairness for the rest of the nation)—New York baseball during the late Forties and Fifties, when my native city boasted three of the greatest teams that ever played our game, a unique confluence that continues to produce a substantial literature of remarkable quality and variety. I dedicate this year’s review to the best years of New York baseball—a symbol for a preservationist battle no less important than any fight ever made to save a building. New York lost its soul when the Dodgers and Giants moved, and when Pennsylvania Station died in wreckers’ rubble.

Wilfrid Sheed, in his introduction to My Life as a Fan, recounts an intellectual’s lament about time spent on sports:

So there they sat for years, the hours spent mulling and brooding, living and dying over various sports, adding up to a monument the size of a small city to wasted time and attention. Other writers might have gold deposits stashed all around their backyards, but I just had this heap of slag….Yet from time to time I would gaze wistfully at my slag heap twinkling in the sun and ask myself whether it might not be worth at least something?

I am delighted that Sheed, a marvelous writer well known to readers of this publication, has decided to join passion with profession—for I regard his book as the best testimony to baseball’s hold upon us, and to its frequent (if threatened) internal beauty, since Roger Angell started writing his incomparable prose.

Sheed entered the world of baseball as a double outsider in childhood—first as a foreigner with Australian and British roots, and second as a proto-intellectual who discovered (as I did) that sports knowledge gives you a niche (marginal perhaps, but still a niche) in boy culture:

He has a place in the gang, though a humble one like a court jester’s. “Ask Sheed—he knows everything.” You have to be a little weird to know all that stuff, and weird can never be the best thing to be, but you’re all right, you’ve turned your powers to benign, good-guy purposes. “What do you do, sit up all night and study that stuff?” There is no right answer to this, but you’re probably better off with “Yes.” It’s better to be a crank than a genius. Otherwise you can try “It’s just a knack,” and try to make up for it with dreadful schoolwork.

Sheed came to Philadelphia in 1940, as a nine-year-old refugee from the Blitz of London. His memories are therefore ten years older than mine, and begin with the bittersweet experience of rooting for a truly terrible local team (the old Philadelphia Athletics). But Sheed soon traded up: “Thank God I had balanced my portfolio with the Brooklyn Dodgers.” He therefore knew, as a young man, the joys of New York baseball at its best, including the transcendent moment for his guys (not for mine), when the Bums beat the Yanks for their only World Series victory in 1955, and he (but not I) experienced “the unholy glee that exploded in a million bars and living rooms and offices and came pouring into the streets of Brooklyn on a wave of pure happiness.”

Personal testimony provides us with the best way to convey the appeal and value of regional, regular season sport; and Sheed’s memories are more telling than most because of his good writing and gentle humor. Consider this description of his first major league game, at the old bandbox of Shibe Park, Philadelphia:

The first game still sits there shining….Aging commuters will remember how the sight of that park brightened the approach to North Philadelphia station. You had only to hop off the train and be in Wonderland (I hopped off myself one day and landed on my nose—you did have to wait until the train stopped). Anyway, it was love at first sight, a love embracing even the light towers and the back of the grandstand. This was going to be a good place. Yes indeed.

Or this anecdote, about Father Felix, one of Sheed’s teachers at his Catholic school, and an avid racing fan:

Clerical sports nuts were as common as daisies in the old American church. So Father Felix was probably not the only priest to start pawing the ground come spring and flaring his nostrils….He would repair [to the track at Monmouth Park, New Jersey] in black pants and a green school windbreaker and bet such dribs and drabs of money as the vow of poverty allowed him. But one day, before he could slide into the men’s room to change into his threadbare disguise, an attendant accosted him in a scary voice with the words “Don’t you go in there, Father!” “Why not? What’s going on in there?” piped Felix, as a good straight man should, and the attendant wound up and unloaded his high hard one on him. “I seen a lot of priests go in there, Father, and I never seen one come out.”

Newspapers and radio supplied the continuity for daily play during the great years of New York baseball. Today, most announcers are interchangeable—little personality and less opinion (though with copious facts dredged from computers about such meaningless arcana as the number of doubles Mr. X hit to the opposite field off Mr. Y in night games at Field Z during 1992). But announcers, particularly on radio where more color and information must be supplied, were once as distinctive and as regionally differentiated as the teams they represented.

New York was fortunate to have two of the greatest announcers, both Southerners with deeply distinctive accents, during the glory years—Mel Allen (from Alabama) with my Yankees, and Red Barber (from Mississippi) with the enemy Dodgers. They differed so sharply, and came to define their teams so intently, that when the Bums fired Barber and the Yankees promptly grabbed him, I just couldn’t adjust. Barber announcing for the Yanks sounded like Tokyo Rose singing God Bless America.

Think of any great rivalry between wonderful talents who basically appreciate and admire each other—Pavarotti and Domingo, DiMaggio and Williams. Allen’s style was pure corn. He rooted with gusto (who can forget his homerun mantra of “going…going…gone”?). I have often thought of the day when fans were booing rookie Mickey Mantle. Allen leaned out of the press box to ask why and he burst out in fury when he received the answer, “Because he’s not as good as DiMaggio.” He touted his advertisers at any opportunity—homeruns were “Ballantine blasts,” and near misses were “foul by a bottle of Ballantine beer.”

Barber, by contrast, was as cool and even as could be: when Bobby Thomson hit his immortal home run to wrest the flag from the Dodgers in 1951, Barber just stated the fact and then let crowd noises fill the air for a full minute—while Giants announcer Russ Hodges babbled with incoherent joy and, in Barber’s opinion, totally unprofessional favoritism. He had more useful information in his head than any modern computer and he made the right connections. He may have spoken without overt passion, but he was a master of words and their uses (including impeccable grammar), and his down-home sayings and phrases illuminated the airways. A wet ball that eluded an infielder was “slicker than oiled okra.” As the Dodger starting pitcher began to falter one day, Barber announced: “There’s no action in the Dodger bullpen yet, but they’re beginning to wiggle their toes a little.” I loved both men.

The very best professionals have such love for their work, and such dedication to their calling, that they cannot stop while life and opportunity remain. Much as I admired Mel Allen and Red Barber in their spring and summer, I think that I appreciate them all the more for their work during their eighties, the winter of their lives. Mel Allen now announces for the Major League’s official television journal This Week in Baseball—and how I still look forward to hearing his animated voice. Red Barber died in October 1992, after twelve years as the star of the most popular program ever to run on National Public Radio—his four-minute weekly chat on Friday morning with Bob Edwards (“Colonel Bob” to Red after Barber learned that Edwards, who comes from Kentucky, had officially received this title, one readily conferred upon natives of the state).

Red treated Bob like a son. They talked about flowers, cats, and the weather in Tallahassee, where Red had retired. They usually (but not always) got around to sports. Red charmed millions of listeners with his courtliness, his civility, his urbanity, his professionalism, his stubbornness in conducting each conversation on his own terms, and his immense knowledge. I admired all these traits, but I listened because I so loved to hear that wonderful voice from my youth. I will also confess to an experience worthy of the old cartoon series, “The Thrill that Comes Once in a Lifetime.” Red spent one of his broadcasts correcting me for misidentifying the last pitch of Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series (I had called it low and outside, but the pitch was high). What a pinnacle: to be corrected by the Old Redhead!—like learning that God himself, or at least the chief Rabbi of all history, deems your work worthy of improvement!

Of course Fridays With Red is a good book; nothing filled with long excerpts from Red Barber could possibly, he bad. But Colonel Bob could have done so much better. He has composed the equivalent of a testimonial or long promotional pamphlet, when be could have written a book about that most elusive, precious kind of relationship, a genuine friendship between men. On the air, Edwards was unassuming, letting Red talk and gently nudging him from topic to topic, and this book contains long and enjoyable extracts from their programs. But I guess the Colonel has been saving his own words for years, and his book contains many editorial statements at too great a length. Moreover, Edwards disrupts his book with long lists of quotations from others, including page after page of eulogistic letters received after Red’s death, with testimonials to Red’s excellence and his own. Red Barber, a man of consummate form and timing, would surely have cut these lines.

Roger Kahn calls the great era of New York baseball “the most important and the most exciting years in the history of sport.” As a sportswriter for the Herald Tribune, Kahn covered all three teams during these years; he described more than 750 daily and postseason games, and knew all the players. Kahn has also written many fine baseball books, including The Boys of Summer, his affectionate and incisive portrait of the men who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, considered by many as the finest baseball book ever written.

Kahn’s new book—The Era: 1947–1957, When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World—wisely violates the conventions of sports writing: the accounts of one game after another interspersed with anecdotes about extracurricular adventures in bars and hotel rooms. Instead, drawing on the technique of the best of TV soaps (and I do not say this at all disparagingly, but in praise), Kahn ties together the three basic stories for the three teams, while also including several interesting subplots and tales about particular players and managers.

Some features of the book seem overly idiosyncratic. Kahn spends a bit too much time on relatively trivial events that happened to involve him. He has also given the book a most curious (and regrettable) imbalance by writing at length about the admittedly thrilling beginning of “The Era” and then hurrying through the equally exciting end. He devotes, for example, a full thirty pages to the marvelous 1947 World Series, describing every game in detail, and for once in the conventional narrative mode (so discordant from the rest of the book that I wonder if this account was left over from an earlier work).

But he then compresses into the same number of pages all the dramatic events of 1954 through 1957: the Giants’ sweep of the 1954 World Series from the Cleveland Indians, the best team in the history of modern baseball (including Willie Mays’s legendary catch off Vic Wertz, and alcoholic utility outfielder Dusty Rhodes’s great moment of batting glory); the one and only victory of the Dodgers in the 1955 World Series (how could Kahn, of all people, downplay this singular triumph over the hated Yankees?); Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series; and the beginning of the California diaspora.

Kahn argues that the earlier years were more dramatic and important, but I suspect that he just ran out of gas. I, for one, would have read one hundred more pages with delight (and the book would only then have reached the length of The Boys of Summer)—for Kahn is the best baseball writer in the business, and shouldn’t scrimp.

New York baseball was a marvel during the days of The Era. Ten of eleven seasons featured at least one New York team in the World Series. Seven World Series were “subway” contests between two New York teams (’47, ’49, ’52, ’53, ’55, and ’56 with Yanks vs. Dodgers, and ’51 with Yanks vs. Giants), while one of ours beat an infidel in two others (Yanks over Phils in ’50, and Giants over Indians in ’54). But the wider appeal of New York baseball lay in the incidents and stories involving the remarkable men who illuminated our athletic stage during The Era.

I didn’t know, for example, that Babe Pinelli umpired at second base in the fourth game of the 1947 World Series. With Yankee Bill Bevens pitching a no-hitter with two outs in the ninth, Pinelli called Dodger Al Gionfriddo safe at second in an attempted steal. Had Pinelli called Gionfriddo out—and Rizzuto, who made the tag, swears to this day that Pinelli was wrong—Bevens would have won his no-hitter. Instead, Cookie Lavagetto doubled to ruin Bevens’s achievement and, almost cruelly, to win the game as well, as two runners, whom Bevens had walked, scored on the hit. Why concentrate upon this incident? Because the same Babe Pinelli, umpiring his last game before his retirement, stood behind the plate when Don Larsen pitched his perfect game in the 1956 World Series—and Pinelli made a controversial final call by declaring Dale Mitchell out on strikes on a pitch that was clearly high and outside (the one that prompted Red Barber’s correction of my error). Was he atoning for a previous miscall?

Kahn writes best about the ruthless, colorful, crude, imperious, and sometimes principled men who played and ruled New York ball during The Era. What crazy confluence could have brought such people as Walter O’Malley, Casey Stengel, and Leo Durocher together, even in so vast a city? The Dodger boss O’Malley never let a fact stand in the way of a tale and moved the Dodgers to California despite continuing enormous profits in Brooklyn. Kahn tells the story of two prominent sportswriters who challenged each other (one night in a bar, of course) to write down the names of the three worst human beings. Each wrote in secret and produced the same list: Hitler, Stalin, and O’Malley. (Just about right, in my opinion.) Dodger fan Wilfrid Sheed agrees as well, for he brands O’Malley as “this monstrous figure, this walking cartoon. He is the villainous Walter O’Malley, against whom this book is dedicated.”

Casey Stengel, who managed the Yanks to a record five World Series victories in a row (’49–’53), sometimes acted like a clown and spoke in syntax so fractured that his style gave the language a new term—Stengelese.* But Stengel only used these mannerisms as a conscious device to lower an enemy’s guard, for he was brilliant and ruthless, a complex man capable of both real tenderness and cutting cruelty. When the Yanks beat the Phils 2–1 in the tenth inning of game two in the 1950 World Series, he remarked: “Yes sir, them Philadelphias is a very fine team, make no mistake. It is difficult to beat them, which is why it took us an extra inning today.” When the Yanks won 3–2 with two out in the ninth inning of game three, he said: “The Philadelphias are very difficult to beat, as I have told you. Why today, as you gentlemen saw, my fine team was unable to beat them again until the very last inning we were permitted to play.” When he took out rookie Whitey Ford for veteran Allie Reynolds to sew up the last game in the final inning, Stengel said: “I’m sorry I had to take the young man out, but as I have been telling you, the Philadelphias is hard to defeat, and I am paid by my employers to defeat them, which is why I went for the feller with the big fastball. Have a nice winter.” Sounds aimless, but edit the relative clauses, introduce some agreement, and you have ordinary English. And look what Casey accomplished: he had swept the opposition in four games, but praised them generously, placated a wounded young pitcher, and tempered a rout with comic relief.

Stengel always knew what he was doing. After losing the 1957 World Series to Milwaukee, and wishing to frustrate a young TV reporter who had asked the uncharitable question “Did your team choke up out there?” Stengel just said “Do you choke up on your fucking microphone?” and then clawed at his rear end. He later said to Roger Kahn: “You see, you gotta stop them terrible questions. When I said ‘fuck’ I ruined his audio. When I scratched my ass, I ruined his video, if you get my drift.” He could also be cruel. When Jackie Robinson criticized the Yanks for not hiring black players, and then struck out three times in a Series game against Allie Reynolds, a Native American Yankee pitcher, Stengel remarked: “Before he tells us we gotta hire a jig, he oughta learn how to hit an Indian.”

Leo Durocher, who started the era as the suspended manger of the Dodgers (ostensibly for gambling and associating with undesirables, but truly for his sexual behavior and general unwillingness to conform), and then led the Giants in the triumphs of ’51 and ’54, was cruel and swaggering on one side, brave and antiracist on the other. When Commissioner Happy Chandler announced Durocher’s suspension in April, 1947, Durocher spoke only one sentence to the reporters at his hotel: “Now is the time a man needs a woman.” He then led his new wife, the beautiful actress Laraine Day, into his suite—and didn’t emerge for forty-eight hours. During spring training, before his suspension, several Dodgers planned a petition to protest the hiring of Jackie Robinson as major league baseball’s first black player. Durocher called a team meeting at one in the morning and told the instigators to “wipe your ass” with the petition. He ended by saying: “I don’t want to see your petition. I don’t want to hear anything about it. Fuck your petition. The meeting is over. Go back to bed.” Robinson had begun his career.

Kahn ends his book by writing: “The Era ended when it was time for the Era to end and that, I believe, is everlastingly part of its beauty and its glory.” This I do not dispute. New York could not dominate a national game forever, while clean and dramatic endings beat extended fizzles. But, earlier in the book, Kahn writes of the 1951 regular season that ended with Thomson’s homerun: “The National League Pennant Race of 1951 belongs to the ages. There has been nothing like it before or since. Nor will it come again.” Sadly, this is true—and for a deeper reason than Kahn realized at the time: there will not be another pennant race at all.

On the Wordsworthian theme—“We will grieve not, rather find Strength in what remains behind”—I take solace in what will prevail through any crass and commercially driven sacrifice of seasonal rhythm and schedule: the beauty of a single game well played, and the common denominator of baseball’s best performers: obsessive striving for excellence, the mark of all true professionalism. In observing an awesome skill that we do not possess, we tend to misread ease of performance as natural inclination. Even Red Barber so erred in asking Fred Astaire whether dancing came easily to him.

I was interested in interviewing Astaire to find out the correlation between his dancing and athletic ability. And to my surprise he said, “Well, I wouldn’t say that dancing comes so easily to me. I work at it. I practice hour after hour,” and suddenly you see a man who does something so effortlessly—seemingly effortlessly—and you find out that each of us who are genuine professionals pays a price.

Intellectuals often make the same mistake in assuming that we struggle to become scholars, while athletes perform by inherited brawn. But Roger Kahn movingly documented the obsessive drive and the incessant practice common to all the Boys of Summer at the Dodgers’ apogee. When Billy Cox or Bobby Brown at third, Phil Rizzuto or Peewee Reese at short, dove to field a grounder with such fluidity; when DiMaggio or Mays ran across a whole field to meet a fly ball with precision; when Furillo threw a bullet from right field to home and Campy tagged the runner out by fifteen feet, we watched the equivalent of a poet’s couplet, stated with perfect grace, but produced by hours of struggle after a lifetime of discipline. As Yeats wrote:

I said, “A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.”

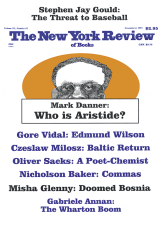

This Issue

November 4, 1993

-

*

This year’s New York baseball books also include two collections from two singular personalities—a Bible of all key statements in and about Stengelese in The Gospel According to Casey by Ira Berkow and Jim Kaplan, and an amusing selection, presented as blank verse but unaltered in text, of the meandering stream-of-consciousness musing developed as a broadcasting style by former Yankee shortstop Phil Rizzuto, in O Holy Cow! The Selected Verse of Phil Rizzuto, edited by Tom Peyer and Hart Seely. ↩