1.

As a war cry, “Geronimo!” has certainly stood the test of time. Paratroopers in World War II yelled it as they hurled themselves into the void, and, more recently, our lethal team of killers were said to have uttered it when they surprised the bin Ladens in their compound in Pakistan. And yet the man who bore it, a Bedonkohe Apache whose tribal name was Goyahkla, was never a chief. When he finally surrendered, to General Nelson A. Miles on September 3, 1886, he had only fifteen men with him, and a few women and children. In his years of constant raiding he rarely led more than thirty men, many of them members of his extended family. At least two of his Apache contemporaries, Mangas Coloradas and Cochise, were far better leaders than Geronimo, and yet his name endures and the others are largely forgotten except by close students of Apache life.

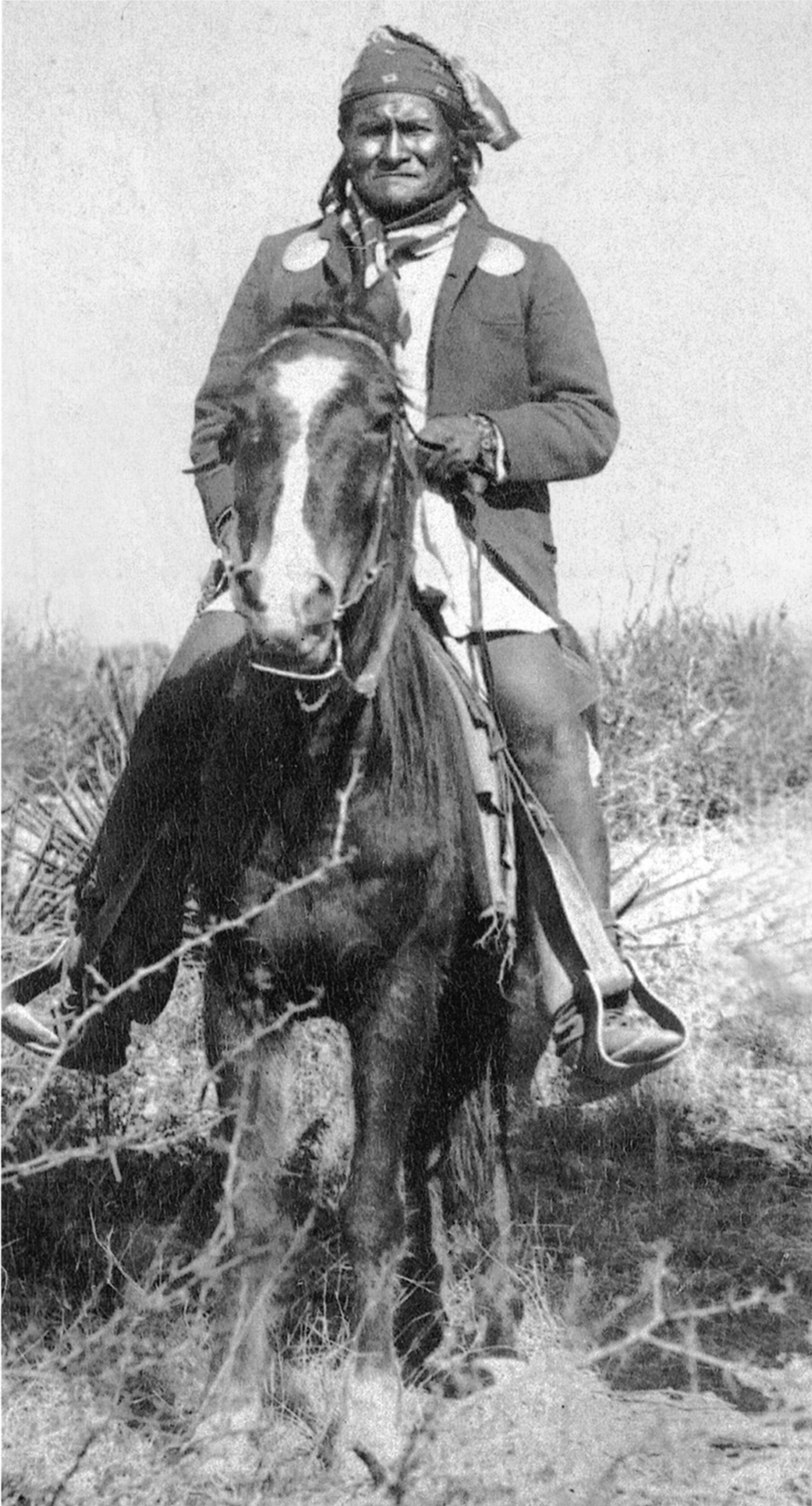

The author of this new biography of Geronimo, Robert M. Utley, evidently enjoys writing about difficult men. His excellent book The Lance and the Shield (1993) is mostly a study of the testy Hunkpapa Sitting Bull, whom Buffalo Bill Cody—who once employed him briefly in his circus—called “peevish,” a major understatement. The same could be said of Geronimo. I don’t recall a photograph of Geronimo smiling, though once in captivity, when he performed at fairs and expositions, he was photographed hundreds of times, and there might be one of him smiling somewhere. At least one of his sons went to the Carlisle Indian School.

Robert Utley is an accomplished and meticulous historian, with a solid grasp of the history of the American West. For long the standard biography of Geronimo was that of the Oklahoma historian Angie Debo, whom I wrote about in these pages a long time ago.* Geronimo was in Oklahoma, at Fort Sill, during the last several years of his life; he died there of pneumonia in 1909. I own, myself, some thirty-five glass negative photographs of Geronimo, taken by a woman dentist while he was in captivity at Fort Sill. In one photograph he is allowed to hold a revolver. He does not look happy.

It is hardly surprising that Geronimo would rarely have been photographed smiling. Few native Americans had much to smile about: less and less as the whites got serious about taking their land. In 1851 Mexican troops hit Geronimo’s camp while he was away. He returned to find his mother, wife, and three children dead in pools of blood. He hated Mexicans for the rest of his life, though over and over again, when pressed by his enemies, he retreated into the fastness of the Mexican Sierra Madre, using the border defensively whenever he needed to.

2.

Geronimo was born in 1823, in the mountains of what is now western Mexico. Until he was finally captured and sent first to Florida and then to Oklahoma, his life was spent in the mountains and deserts of New Mexico and Arizona, and in Mexico proper when he felt the need.

He was not likable. Utley quotes an Apache contemporary who said that he had known Geronimo his whole life and could not think of a nice thing to say about him. Neither could the prickly General George Crook, who chased Geronimo uphill and down but could not quite coax him in. Geronimo felt that Crook “talked ugly” about him, whereas Miles spoke courteously to him. Finally he was coaxed into Miles’s camp in Skeleton Canyon and his days as a raiding Apache were over.

The most engaging book about the duel with Geronimo is On the Border with Crook (1891), by John Gregory Bourke, Crook’s aide-de-camp, who went on to write a once-famous work of anthropology called Scatologic Rites of All Nations (1891). The Indians called Bourke the paper medicine man. He also wrote a hard-to-come-by study of the Moqui Indians, who were snake handlers.

Geronimo probably did not understand that neither Crook nor Miles would be the one to decide his eventual fate. The Apaches were people of the mountains. The decision of the US authorities to send them to the Florida lowlands did not work very well.

Geronimo did better in Oklahoma, where he rode in many parades, sometimes with his tall, handsome neighbor Quanah Parker, principal chief of what was left of the Comanches. Quanah was the half-white son of the most famous white captive, Cynthia Ann Parker—her captivity was thought to be the source of the famous John Ford movie The Searchers. Quanah was very good-looking and had many wives. His only Native American rival in the looks department was the famous Chief Gall, a man so striking that he impressed even the Indian-hating Libbie Custer, the general’s widow. Geronimo, too, had a bunch of wives: eight by Robert Utley’s calculation.

Advertisement

Utley has done a serviceable job of tracking Geronimo through his many raids. His culture was a raiding culture. The Apaches did their best to repulse the whites who were crowding into their country, but first gold, then silver, then copper were discovered in New Mexico and Arizona and their raids were of no use. They were too badly outgunned.

Utley has followed Geronimo skillfully through his various escapes from Union soldiers, which come to seem a little repetitious. The plotting that led to Geronimo’s eventual capture will mainly interest close students of Arizona history. Geronimo was probably happy to outlive his old nemesis, George Crook, who died in 1890.

I personally find Sitting Bull more interesting than Geronimo. His great vision dance before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, with soldiers falling like grasshoppers into his camp, still resonates. And Sitting Bull had a chaste crush on Annie Oakley and a not-so-chaste one on a lady philanthropist from Brooklyn. Geronimo did nothing quite so interesting.

Still, while remaining under guard as a prisoner of war, he ended up as a kind of American celebrity. At the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition of 1898 in Omaha, Nebraska, and later in such cities as Buffalo and St. Louis, Geronimo was, Utley writes, a star attraction, posing for photographs, selling craftwork, participating in mock skirmishes, and performing some of the incantations that were part of his healing ceremony. “For the rest of his life, he was in constant demand…at fairs large and small.”

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right

-

*

“Broken Promises,” The New York Review, October 23, 1997. ↩