Late in the 1970s Americans began noticing more people sleeping in public places, wandering the streets with their possessions in shopping bags, rooting through garbage bins in search of food or cans, and asking for handouts. By January 1981, when Ronald Reagan took office, a small group of activists led by Robert Hayes and Mitch Snyder had given these people a new name—“the homeless”—and had begun to convince the public that their plight was a serious one. Later that year America entered its worst recession in half a century, and the homeless became far more numerous. At the time, many people saw this as a temporary problem that would vanish once the economy recovered, but they were wrong. Unemployment fell from almost 10 percent in 1983 to just over 5 percent in 1989, but homelessness kept rising.

The spread of homelessness disturbed well-to-do Americans for both personal and political reasons. The faces of the homeless often suggest depths of despair that we would rather not imagine, much less confront in the flesh. Daily contact with the homeless also raises troubling questions about our moral obligations to strangers. Politically, the spread of homelessness suggests that something has gone fundamentally wrong with America’s economic and social institutions.

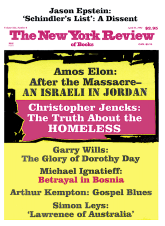

Because homelessness is both deeply disturbing emotionally and controversial politically, it has inspired a steady flow of books and reports by journalists, political activists, and scholars.1 These publications cover a multitude of different issues, but I will concentrate on what they can tell us about three questions: how much homelessness increased during the 1980s, why it increased, and what we can do to reduce it.

1.

As soon as homelessness became a political issue, legislators and journalists began asking for numbers. The Census Bureau was in no position to answer their questions, because it had always counted Americans by making lists of “dwelling units” and then trying to determine how many people lived in each unit. The bureau had never made much effort to count people living in bus stations, subways, abandoned buildings, parks, doorways, or dumpsters. Nor did it try to fill this gap when public interest in the homeless exploded in the early 1980s. Even the 1990 Census, which attempted a systematic count of people in various kinds of shelters, made only a half-hearted effort to count the roughly equal number of homeless adults who were not in shelters.2

In the absence of official statistics, both journalists and legislators fell back on estimates provided by activists. In the late 1970s Mitch Snyder argued that a million Americans were homeless. In 1982 he and Mary Ellen Hombs raised this estimate to between two and three million.3 Lacking better figures, others repeated this guess, usually without attribution. In due course it became so familiar that many people treated it as a well-established fact.

Widespread acceptance of Snyder’s estimate apparently convinced the Reagan administration that leaving statistics on homelessness to private enterprise was a political mistake, and in 1984 the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) undertook a survey by telephone of social relief agencies and other informants in each large American city, asking them to estimate the number of homeless people in their area. Extrapolating from these responses, HUD’s “best estimate” was that between 250,000 and 350,000 people were homeless in the nation as a whole.4

This estimate was so much lower than Snyder’s that many skeptics assumed HUD must have distorted the data. But when Ted Koppel asked Snyder where his figures had come from, this is what Richard White, the author of Rude Awakenings, quotes Snyder as having said:

Everybody demanded it. Everybody said we want a number… We got on the phone, we made lots of calls, we talked to lots of people, and we said, “Okay, here are some numbers.” They have no meaning, no value.

Nonetheless, Snyder denounced HUD’s numbers as “tripe.” If HUD’s numbers were accepted, he told Koppel, they would “take some of the power away…some of our potential impact…and some of the resources we might have access to, because we’re not talking about something that’s measured in the millions.”

Snyder was right. Big numbers are politically useful. That is why many advocates for the homeless still claim that several million Americans are homeless on a given night, even though no careful study has ever yielded a nightly count that high. White describes the repetition of these inflated estimates as “lying for justice.”

HUD’s estimates were more systematic than Snyder’s, but they were still based largely on adding up guesses. The first careful count I know of came only in September 1985, when Peter Rossi made a survey of the homeless in Chicago—a city where advocates claimed that between 15,000 and 25,000 were homeless on an average night.

Rossi tried to count everyone sleeping either in a public place, such as a doorway or a park, or in a free shelter. Counting the shelter population was easy. To count the street population, Rossi had interviewers search a random sample of city blocks during the small hours of the morning, looking in every space they could reach without encountering a locked door or a security guard. This was potentially dangerous work, so his interviewers worked in pairs and were accompanied by off-duty policemen. The interviewers asked everyone they found, awake or asleep, whether they had a home elsewhere. Nine out of ten said they did. Since Rossi paid his respondents, almost everyone answered his questions.

Advertisement

Down and Out in America describes what Rossi found. Extrapolating from the blocks he searched, he estimated that about 1,400 homeless adults were sleeping on the Chicago streets or in publicly accessible buildings such as bus stations, airports, allnight movie theaters, and restaurants. Another 1,400 adults and children were in shelters. That brought the overall count to about 2,800. When Rossi did a second survey during the winter of 1986, cold weather had lowered the street count and raised the shelter count, but the city’s estimated homeless population was still about 2,500. Since Chicago had almost 3 million residents at the time, these estimates imply that just under 0.1 percent of the city’s population was homeless. That was about the same as HUD’s 1984 estimate for the nation as a whole.

Rossi’s procedures probably missed more than a few homeless people. No early morning street count is likely to find everyone who is homeless. In order to avoid being robbed, assaulted, rained on, or frozen, the homeless often try to conceal themselves, preferably indoors. Some sleep in basements and hallways whose owners make the space available at night in return for daytime work. Some sleep in abandoned buildings, often with makeshift locks on the door. Some spend the night in “shooting galleries” for drug users.

In New York, an early morning street count would probably miss even more people than in Chicago. Manhattan is honeycombed with underground tunnels, most of which were built in the nineteenth century either for the city’s new subway system or for the railroads that converged on the city. Many of these tunnels have been abandoned, but most can still be reached from the streets. Jennifer Toth, the author of The Mole People, explored this labyrinth during 1990 and 1991 accompanied by diverse and sometimes terrifying guides. She concluded that at least 5,000 people lived in the tunnels. An outreach program funded by the Metropolitan Transit Authority in 1990 put the figure even higher, claiming that over 6,000 people were living under Grand Central and Penn Stations alone. About twice that number of single adults sleep in the city’s shelters on an average night.

Because the homeless often try to disappear at night, many investigators interview them during the day, when they make less effort to conceal themselves. The most comprehensive survey of this kind was conducted by the Urban Institute during March 1987 in a representative sample of cities with more than 100,000 residents. Interviewers talked with randomly selected adults in shelters, soup kitchens, and “congregating sites” frequented by the homeless, such as bus stations, parks, and street corners.

Martha Burt, who directed this survey, summarizes many of its findinqs in Over the Edge. Her work suggests that only a third of all single homeless adults slept in a shelter the night before they were interviewed. Among families with children, in contrast, 96 percent had slept in either a shelter or a welfare hotel.5 If these ratios also hold for smaller communities, as they seem to, about 325,000 single adults and 65,000 members of families with children were homeless on a typical night in March 1987.6

Far more people become homeless at some time during a year than are homeless on any given night. In 1990, Bruce Link and a group of colleagues at Columbia University asked a national sample of adults with telephones about their experiences with homelessness. Three percent said they had spent time in a shelter or on the streets during the past five years.7 If we allow for the responses of people who had no telephones, that would mean six or seven million people had been homeless at one time or another between 1985 and 1990. Roughly speaking, at least 100,000 people became homeless every month, while another 100,000 returned to conventional housing.8

Link’s survey suggests that half of those who became homeless got off the streets within a couple of months. Only one in eight remained homeless more than a year. But while most spells of homelessness were quite short, the long-term homeless still account for about half of those who are homeless on any given night.9

We have no good national data on the size of the homeless population before Burt’s 1987 survey. White suspects that the number may not have risen at all. He thinks activists like Snyder and Hayes persuaded liberal journalists eager to discredit the Reagan administration that an age old problem was out of control without having any hard evidence.

Advertisement

When I first read White’s book, I dismissed this theory as ridiculous, on the grounds that city streets looked completely different in the late 1980s from those in the late 1970s. But what we see on the streets often depends more on police practices than on the frequency of destitution. The number of panhandlers, for example, depends mainly on the risk of arrest and how much one can earn from panhandling compared to other activities. Most panhandlers appear to live in conventional housing, and only a minority of the homeless admit to panhandling. Nor is appearance a reliable indicator of homelessness. Rossi’s interviewers rated more than half their respondents “neat and clean.”

Shelter counts provide stronger evidence that homelessness increased. Census data suggest that five times as many people were using shelters in 1990 as in 1980. We do not have national data on the proportion of the homeless sleeping in shelters in either year, but no local study suggests that it rose by anything like a factor of five. 10 It follows that the overall homeless population must have grown.

From all the studies I have seen, I would guess—no one can do more than that—that the homeless population grew from about 125,000 in 1980 to around 400,000 in 1987–1988 and then fell to around 325,000 in 1990. (See Table 1.)

The post-1988 decline could, however, be a byproduct of sampling error in HUD’s 1988 shelter survey.

HUD no longer conducts shelter surveys, and I know of no reliable data on national trends since 1990. Even the Clinton administration’s draft report on homelessness relies entirely on data collected in 1990 or earlier. Shelter counts from the cities with which I am familiar show no consistent trend since 1990.

2.

As soon as Americans noticed more men and women living in the streets during the late 1970s, they began trying to explain the change. Since some of these people behaved in bizarre ways, and since everyone knew that state mental hospitals had been sending their chronic patients “back to the community,” many sidewalk sociologists (including me) initially assumed that most of these people were former hospital inmates.

Taken literally, this theory turned out to be wrong. Surveys conducted during the 1980s typically found that only a quarter of the homeless admitted to having spent time in a mental hospital. (See Table 2.)

But that does not tell us how many of the homeless were mentally ill. Some who have been in mental hospitals are reluctant to say so. Moreover, not everyone who is mentally ill has been in a mental hospital, and not everyone who has been in a mental hospital is still mentally ill.

Clinicians who examine the homeless typically conclude that about a third have “severe” mental disorders. The homeless seem to share this view of their mental health. A third of Rossi’s Chicago sample said that they could not work because of “mental illness” or “nervous problems.”

Rossi also asked homeless adults whether they had had any of the following experiences within the past year:

Hearing noises or voices that others cannot hear.

Having visions or seeing things that others cannot see.

Feeling you have special powers that other people don’t have.

Feeling your mind has been taken over by forces you cannot control.

About a third of the Chicago homeless reported having had at least one of these experiences at a time when they were neither drunk nor taking drugs. While no one symptom is ever definitive, delusions of this kind are usually linked to schizophrenia. The homeless are also more likely than other people to be depressed, confused, angry, paranoid, and solipsistic.

People who work with the homeless often argue that these problems are a predictable byproduct of living on the streets. In some cases this is surely true. When natural disaster or war drives random victims from their homes, many become acutely depressed, and some grow suicidal or have mental breakdowns. But even when victims of famine and war have spent years in refugee camps far worse than any Chicago shelter, no one has ever reported that a third of them saw visions or heard voices. The fact that a third of the Chicago homeless had such delusions suggests that many had serious mental problems even before they started living on the streets.

My guess is that more than a third of today’s homeless would have been in hospitals during the 1950s. Sleeping in public places was then illegal, and few shelters accepted applicants who appeared crazy. People who were homeless and showed signs of mental illness had frequent run-ins with the police. If they had no place to go, the police routinely took them to a mental hospital for evaluation. Psychiatrists, in turn, treated homelessness as evidence that a patient could not cope with the stresses of everyday life and needed professional care. As a result, the homeless were likely to be hospitalized even when their symptoms were relatively mild. Dismantling this system has, I think, played a major part in the spread of homelessness.

Those who advance this argument must, however, answer at least one obvious objection. The fraction of the adult population sleeping in state mental hospitals fell from 0.47 percent in 1955 to 0.12 percent in 1975 without any apparent increase in homelessness. Why, then, should deinstitutionalization have suddenly begun to produce widespread homelessness after 1975? The answer is that deinstitutionalizing was not a single policy. Rather, it was a series of quite different policies, all of which sought to reduce the number of patients in state mental hospitals, but each of which moved these patients to a different place. The policies introduced before 1975 worked quite well. Those introduced after 1975 worked very badly.

The first round of deinstitutionalizing began in the 1950s, after leaders of the psychiatric profession became convinced that long-term hospitalization usually did patients more harm than good. After 1955, when new drugs like thorazine began making patients easier to live with, hospitalization rates began to fall steadily.

Congress set off a second round of deinstitutionalization in 1965 when it created Medicaid. Medicaid did not cover patients in state mental hospitals, but it did cover short-term psychiatric care in general hospitals, and it also covered patients in nursing homes. As a result, states began moving chronic patients to nursing homes and sending patients who needed acute care to the psychiatric wards of general hospitals.

In 1972 Congress established Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which provided a monthly check to anyone whom the Social Security Administration judged incapable of holding a job. Mental patients could not collect SSI while they were in a state mental hospital, but they became eligible as soon as they were discharged. State hospitals therefore began discharging patients to private “board and care” facilities that were set up by entrepreneurs in private houses, converted nursing homes, and run-down apartment houses. When patients entered such facilities, they signed over their SSI check to the management and lived pretty much as they had in state hospitals: eating, sleeping, taking their medicine, watching television, playing cards, and talking with fellow inmates. But now Washington paid most of the bills.

Federal SSI benefits (including food stamps) are currently just over $500 a month. That seems to be enough to keep the frugal elderly off the streets. (Only about 10,000 people over the age of sixty-five were homeless in 1987–1988.) But board-and-care facilities that get only $500 per patient every month cannot afford to provide much supervision. That means they can only afford to admit the mental patients who can care for themselves and cause no trouble. Those who need more intensive care must go elsewhere.

By the mid-1970s most state mental hospitals had discharged almost everyone whom they could get someone else to care for. Their remaining inmates were either chronic patients whom nobody else wanted or short-term patients getting acute care. But advocates of deinstitutionalization were far from satisfied. During the 1960s a group of civil libertarians inspired by Thomas Szasz had argued that states should not be allowed to lock up the mentally ill unless they broke the law. By the early 1970s a number of judges had accepted this argument and had begun issuing orders restricting involuntary commitment. The Supreme Court encouraged this trend throughout the decade. In 1975, for example, it ruled in O’Connor v. Donaldson that mental illness alone was insufficient justification for involuntary commitment. By 1980 almost every state had rules that prevented hospitals from locking up patients for more than a few days unless they posed a clear danger to themselves or others.

Once these rules were in place, seriously disturbed patients began leaving state hospitals even when they had nowhere else to live. When their mental condition deteriorated, as it periodically did, many broke off contact both with the mental health system and with the friends or relatives who had helped them deal with other public agencies. As a result, many lost the disability benefits to which they were theoretically entitled. In due course these lost souls often ended up not only friendless but penniless and homeless.

By the end of the 1970s, slow economic growth and a nationwide tax revolt were putting enormous pressure on states to cut their outlays. Meanwhile, federal regulations were forcing states to improve conditions in their hospitals. So instead of trying to persuade chronic patients with nowhere else to live that they should remain in a hospital, state mental health systems began encouraging such patients to leave. Once the courts broke the taboo against discharging patients to the streets, states found the practice very appealing, and it spread rapidly. By 1990 only 0.05 percent of the adult population was sleeping in a state hospital on an average night.

States could have kept many of these people off the streets by finding them a rented room and paying the rent directly to the landlord. But once civil libertarians endowed the mentally ill with the same legal rights as everyone else, state politicians felt free to endow them with the same legal responsibilities as everyone else, including responsibility for paying their own rent. Not surprisingly, many ended up on the streets. States compounded the problem by cutting their cash payments to the mentally ill. Most states had supplemented federal SSI benefits for the disabled during the 1970s. Almost all states let these supplements lag behind inflation during the 1980s. 11 While most states spent more on subsidized housing for the mentally ill, no state guaranteed the mentally ill a place to live.

Federal cutbacks played a surprisingly small part in this debacle. The Reagan administration tightened eligibility standards for federal disability benefits in 1981, but this effort was abandoned in 1983, and by the time Reagan left office the fraction of the working-age population collecting such benefits was as high as it had been in 1980. The proportion of new beneficiaries with mental rather than physical disabilities was also twice as high in the late 1980s as in the late 1970s. The percentage of working-age adults getting federal benefits for a mental disability was thus higher in 1990 than ever before in American history.

Nonetheless, federal benefits did not expand fast enough to offset the effect of changes in the way states ran their mental health systems. Something like 1.7 million working-age Americans had mental problems so severe they could not hold a job in 1987. Roughly 100,000 of these people were homeless. That figure may have fallen somewhat since 1987, but few think it has fallen much. No other affluent country has abandoned its mentally ill to this extent.

Both liberals and conservatives blame this disaster on their opponents, and both are half right. The catastrophe resulted from a combination of liberal policies aimed at increasing personal liberty with conservative policies aimed at reducing government spending. It is important to remember, however, that while liberals succeded in deinstitutionalizing most of the mentally ill, their conservative opponents never managed to cut government spending on the mentally ill. All the conservatives did was slow the rate of budgetary growth. Measured in 1990 dollars, state mental hospitals spent $7.7 billion in 1990, up from $6.5 billion in 1979. Expenditures on residential services for out-patients also rose.12 States cut their SSI supplements, but these were very small to begin with.

3.

When the spread of homelessness accelerated in the early 1980s, most people blamed the economy. Every survey shows that the people most vulnerable to homelessness are unmarried men between the ages of twenty-one and sixty-four who have no job and incomes below $200 a month in 1989 dollars. After adjusting for inflation, one finds that 1.3 million men in conventional housing had these characteristics in 1969. The figure edged up a bit during the 1970s, reaching 1.6 million in 1979. Then the growth rate accelerated, and by 1984 the number was 3.1 million. About a third of these men were black. This surge in extreme poverty surely played a major part in the spread of homelessness during the early 1980s.

Unemployment and severe poverty spread because the economy had a growing surplus of unskilled male workers. That had two effects. First, the relative wages of unskilled men fell. Second, the male workers who were least in demand had trouble finding work at any wage. These men’s problems were exacerbated by growing competition from third world immigrants who were widely believed to be more reliable and more diligent than the native-born workers available at comparable wages.

For the potentially homeless, declining demand for day labor probably had a particularly devastating effect. Alcoholics, drug users, and the mentally ill often need jobs in which they can work on their good days while staying home on their bad days. If they have to show up every day, they are likely to get fired. If they can work irregularly, they can often earn enough to stay off the street. There are no official statistics on day labor, but everyone seems to agree that demand has fallen, and many observers claim that such demand as still exists is mostly met by immigrants.

Women also became more vulnerable to homelessness during the 1980s, but this was not because their job prospects worsened. The proportion of women with personal incomes below $2,500 fell during the 1980s, just as it had during the 1970s. Women became more vulnerable because the minority who did not work were less likely to have husbands. Few unskilled women can earn enough to support a family on their own. For many, therefore, the choices were stark. They could work, refrain from having children, and barely avoid poverty, or they could not work, have children, collect welfare, and live in extreme poverty. Many became mothers even though this meant extreme poverty.

Determined to reverse this disturbing trend, many states tried to make single motherhood less attractive. To do this they let cash welfare benefits lag further and further behind inflation. That did not stop the spread of single motherhood, but it did reduce many single mothers’ money income.13 The number of single mothers living on their own and reporting cash incomes below $5,000 a year rose from 600,000 in 1979 to 1.0 million in 1984 and 1.4 million in 1989. This increase goes a long way toward explaining the spread of family homelessness.

Although economic vulnerability increased both for single mothers and childless men during the 1980s, the timing differed. Among single mothers, vulnerability increased during both the early and late 1980s. Among single men, vulnerability soared in the early 1980s when the economy was slack but dropped slightly after 1984 as growth resumed. That means we must look elsewhere for an explanation of why homelessness continued to spread in the late 1980s among single men. The arrival of crack is the most obvious possibility.

4.

Until the mid-1980s the poor had relied largely on alcohol to help them forget their troubles. This was not because they found alcohol more satisfying than other drugs. They relied on alcohol because, being legal, it was comparatively cheap. Drugs like heroin and cocaine were so expensive in the early 1980s that many surveys of the homeless did not even bother to ask about them.

Alcoholism has been a major cause of homelessness for generations, but there is no evidence that it became more common after 1980. Surveys conducted during the 1980s typically concluded that about a third of the homeless had serious alcohol problems. Surveys of skid row residents conducted earlier in the century typically came up with similar estimates. Thus if we ask why the very poor have gotten poorer, or why so many of them have moved from skid row flophouses to shelters and the streets, alcohol is not a promising explanation.

Crack changed this picture dramatically. It produced a shorter high than other forms of cocaine, but it was also much cheaper. When it first became available around 1985, a single hit typically cost $10. By 1990 the price was often $5 and sometimes as low as $3. Like the half-pint whiskey bottle, crack made the pleasures of cocaine available to people who had very little cash and spent whatever they had on the first high they could afford. By 1990 it was available almost everywhere the homeless congregated.

Surveys that ask Americans about alcohol consumption always find that households claim to buy far less than the manufacturers claim they sell. Such underreporting is likely to be even more common when we ask about drug use, which is illegal. The only reliable source of data on such matters is likely to be urine samples. Information from them is scarce but instructive.

In 1991, Mayor David Dinkins of New York appointed a commission chaired by Andrew Cuomo to advise the city on how it should deal with the homeless. Cuomo was convinced that the homeless needed social services as well as housing. In an effort to demonstrate this point, the commission asked a large sample of New York City shelter users for anonymous urine samples. Participation was voluntary. According to the Commission’s report, The Way Home, 66 percent of the single adults tested in New York’s general-purpose shelters had traces of cocaine in their urine.14 In family shelters, the figure was 16 percent. Cocaine only remains in a user’s urine for two to three days, so roughly two thirds of the single adults tested in general-purpose shelters must have been using cocaine fairly regularly.

Those who assume that New York is the crack capital of the world may be tempted to dismiss these findings as unrepresentative of other American cities. But while drug use seems to be more common in New York than in most other cities, the difference is not as large as most people imagine. The best comparative data come from the police, who now routinely screen for drug use the people they arrest. Among men arrested during 1990 in Manhattan—the only New York borough for which I could find data—65 percent tested positive for cocaine. America has seven other cities with more than a million inhabitants: Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, San Diego, Detroit, and Dallas. Among men arrested in these seven cities during 1990, 49 percent tested positive for cocaine.15 The figures for smaller cities were lower, but not a lot lower.

In New York, therefore, cocaine use was about as common among adults in general-purpose shelters as among people arrested. If that rule holds for other big cities, about half the single men and women who used general-purpose shelters in the nation’s largest cities were frequent crack users. In smaller cities the figure would probably be more like a third. Even if the New York City’s shelters are unusual in having as many crack users as its jails, the Cuomo Commission’s findings suggest that crack is now as big a problem as alcohol.

Some who work with the homeless still argue that drug use, like mental illness, is a consequence rather than a cause of homelessness. This is undoubtedly true in some cases; but it is also true that heavy drug use makes marginally employable adults even less employable, eats up money that would otherwise be available to pay rent, and makes people’s friends and relatives less willing to shelter them. Under these circumstances it would be a miracle if heavy drug use did not increase the odds of becoming homeless.

Drug use also makes it harder for the homeless to get back into conventional housing. A bed in a New York or Chicago cubicle hotel currently costs about $8 a night. Anyone with enough money to buy substantial amounts of crack can therefore afford a cubicle. Nonetheless, many of these men and women apparently sleep in shelters, in the streets, or underground, presumably because they value another high more than they value a tiny, nasty cubicle of their own.

No one knows how many of the homeless could get off the streets if they stopped buying drugs and alcohol, but it is certainly safe to assume that many spend much of their income on such substances. Knowing this, some people conclude that giving the homeless more money will do them no good and may actually make them worse off, at least as far as their medical condition is concerned. But arguments of this kind are very slippery. Suppose that half the money you give to the homeless ends up buying mind-numbing substances that make homelessness more bearable, and that half ends up providing coffee, doughnuts, and bus fare to see a friend. Only fools imagine that every dollar they give others will be spent in ways they approve of. If even a third of the money we gave the homeless improved the quality of their lives, it would probably do more for human welfare than most of what we spend on ourselves.

5.

Despite all the evidence that mental illness and substance abuse play a big role in long-term homelessness, some knowledgeable people still insist that the homeless are mostly people “just like you and me.” The best recent version of this age-old argument is probably Down on Their Luck, by David Snow and Leon Anderson. Snow and Anderson studied Austin, Texas, during the early 1980s, using an elaborate combination of statistical and ethnographic methods. As their title suggests, their book seeks to persuade readers that the homeless—or at least the Austin homeless in the early 1980s—were usually just ordinary people who had hit a stretch of bad luck.

The “bad luck” theory of homelessness is another of the many partial truths that have confused discussions of the homeless. Individual success and failure are the cumulative product of many influences, of which luck is always one. If you study people who have climbed to the pinnacles of American society, you usually find that they have had “all the advantages.” Most started life with competent parents, had more than their share of brains, energy, or charm, and then had unusual good luck. Without any one of these advantages they might still have done well, but seldom as well as they did.

The same rule applies at the bottom of the economic ladder. Those who end up on the street have typically had all the disadvantages. Most started life in families with a multitude of problems; indeed, many came from families so troubled that the children were put in foster care. Nearly half also have black skins. Many had serious health and learning problems. A large proportion grew up in dreadful neighborhoods and attended mediocre schools or worse. After that, most had more than their share of bad luck in the labor market, in marriage, or both. It is the cumulative effect of all these disadvantages, not bad luck alone, that has made them homeless.

For a diametrically opposite view of the homeless, one can turn to David Wagner’s Checkerboard Square: Culture and Resistance in a Homeless Community. Wagner did extensive interviews with the homeless in an unnamed New England city during the late 1980s. While Snow and Anderson see the homeless as victims of bad luck, Wagner sees them as victims of physically and emotionally abusive families. Unlike Snow and Anderson, who try to make liberals identify with the homeless by making them seem much like everyone else, Wagner is a radical who portrays the homeless as fighting back against an oppressive society. He therefore emphasizes behavior that Snow and Anderson play down, such as refusal to be “tied down” by oppressive jobs and marriages, as well as constant bouts of substance abuse. Ironically, this portrait is consistent with the views of many conservatives, who also see the homeless as rebellious and delinquent.

Debates about the relative importance of “luck” and “choice” in making people homeless are in large part arguments about blame. Conservatives want to blame the homeless for having chosen their fate, while liberals want to blame society for having imposed this fate on reluctant victims. But this “either-or” choice makes no sense. In most cases both individuals and society are responsible for homelessness. If no one drank, took drugs, lost touch with reality, or had trouble holding a job, homelessness would be rare. But if America had a system of social welfare comparable to that of Sweden or Germany, homelessness would also be rare. In those countries job training is far better, unskilled jobs pay better, benefits for the unemployed are almost universally available, and the mental health system does much more to provide housing for the mentally ill. It is the combination of widespread individual vulnerability and collective indifference that leaves so many Americans in the streets.

Consider substance abuse. America has had unusually high levels of drug and alcohol abuse for generations. No one knows exactly why this is the case, but substance abuse is clearly an integral part of our culture. Yet that does not mean individuals bear no responsibility for substance abuse or its consequences. Homelessness spread during the 1980s partly because criminal entrepreneurs made cocaine available in smaller doses at lower cost. Surely some especially unpleasant place in hell should be reserved for these business pioneers. Yet that does not mean the customers who succumbed to this new form of temptation bear no responsibility for what it did to them.

Even in the world’s most commercialized society, blame is still free. That means there is still plenty for everyone. The question we ought to ponder is not how to distribute blame but how to change both institutions and individuals so fewer people end up in the streets. I return to that problem in my second article.

(This is the first part of a two-part article.)

This Issue

April 21, 1994

-

1

In addition to the books discussed in this essay, my shelf of recent contributions includes Gregg Barak, Gimme Shelter: A Social History of Homelessness in Contemporary America (Praeger, 1991); Alice Baum and Donald Burnes, A Nation in Denial: The Truth about Homelessness (Westview Press, 1993); Joel Blau, The Visible Poor: Homelessness in America (Oxford University Press, 1992); Philip W. Brickner, Linda Keen Scharer, Barbara A. Conanan, Marianne Savarese, and Brian C. Scanlan, editors, Under the Safety Net: The Health and Social Welfare of the Homeless in the United States (Norton, 1990); Michael Dear and Jennifer Wolch, Malign Neglect: Homelessness in an American City (Jossey-Bass, 1993); Benedict Giamo, On the Bowery: Confronting Homelessness in American Society (University of Iowa Press, 1989); Benedict Giamo and Jeffrey Grunberg, editors, Beyond Homelessness: Frames of Reference (University of Iowa Press, 1992); Stephanie Golden, The Women Outside: Meanings and Myths of Homelessness (University of California Press, 1991); Julee H. Kryder-Coe, Lester Salamon, and Janice Molnar, editors, Homeless Children and Youth: A New American Dilemma (Transaction Publishers, 1991); Henry Miller, On the Fringe: The Dispossessed in America (Lexington Books, 1991); Karen Ringheim, At Risk of Homelessness: The Roles of Income and Rent (Praeger, 1990); Steven Vanderstaay, Street Lives: An Oral History of Homeless Americans (New Society Publishers, 1992); and James Wright, Address Unknown: The Homeless in America (Aldine de Gruyter, 1989). ↩

-

2

The Census Bureau did try to count people who were visible between 2:00 and 4:00 AM in public places frequented by the homeless, but it did not ask them whether they were in fact homeless. When interviewers do ask this question, at least half those queried say that they live in conventional housing. ↩

-

3

Mary Ellen Hombs and Mitch Snyder, Homelessness in America: A Forced March to Nowhere (Washington: Community on Creative Non-Violence, 1982). ↩

-

4

See “A Report to the Secretary on the Homeless and Emergency Shelters” (Washington: Office of Policy Development and Research, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1984). ↩

-

5

These estimates are based on tabulations that Burt made at my request. I discuss them at length in the appendix of my forthcoming book, The Homeless (Harvard University Press). Unless I indicate otherwise, all the numbers in this review come from that book and are documented there. ↩

-

6

Burt herself put the total somewhat higher in an influential paper for the Census Bureau titled “Developing the Estimate of 500,000 to 600,000 Homeless People in the United States in 1987” (see Cynthia Taeuber, editor, Enumerating Homeless Persons: Methods and Data Needs, US Bureau of the Census, 1991). For reasons I discuss in The Homeless, I believe her data imply a one-night count closer to 400,000, but the difference is of little practical importance. ↩

-

7

Bruce Link, Ezra Susser, Robert Moore, Sharon Schwartz, Elmer Streuning, and Ann Steuve, “Reconsidering the Debate about the Size of the Homeless Population,” paper presented at the American Public Health Association meetings in October 1993. Link’s work was the basis for the Clinton administration’s widely publicized claim, in a recently leaked draft report, that seven million people had been homeless between 1985 and 1990. ↩

-

8

My monthly estimate of 100,000 is an “unduplicated” count, in which no individual appears more than once over the course of five years. If we were to include people who became homeless more than once, the monthly incidence of homelessness would be considerably higher. ↩

-

9

To see why this is so, imagine a shelter in which half the beds are occupied by people who stay for a week and half by people who stay for a year. In such a shelter, 96 percent of the new entrants will be short-term residents, but only 50 percent of the beds will be occupied by short-term residents. ↩

-

10

Irwin Garfinkel and Irving Piliavin survey these local studies in “Homelessness: Numbers and Trends,” New York: Columbia School of Social Work, 1994. ↩

-

11

The federal component of SSI is indexed to inflation, but state supplements are not. About half the states currently supplement federal SSI payments, but only Alaska, California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin currently add more than $100 a month to the basic federal allotment. ↩

-

12

For data on mental hospitals see Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1993, Table 195, and for 1987, Table 159. For data on residential services for out-patients see Burt’s Over the Edge. ↩

-

13

Between 1980 and 1990 the personal consumption expenditure deflator from the national income accounts rose 61 percent. Meanwhile, welfare benefits for a single mother with two children and no other reported income rose 26 percent in the median state. See House Committee on Ways and Means, 1992 Green Book, p. 645. The income figures in the text should not be taken too literally. They do not include the cash value of food stamps, housing subsidies, or subsidized medical care, and they are not adjusted to take account of underreporting. But there is no evidence that these biases were appreciably greater in 1989 than in 1979. The value of Medicaid benefits rose during the 1980s, but that did not help single mothers pay their rent. The proportion of welfare mothers getting federal housing subsidies also grew, but nothing like enough to offset the decline in their cash benefits. ↩

-

14

Eighty percent of those in general-purpose shelters for single adults tested positive for some mind-altering substance. Among single adults who tested positive, 83 percent had used cocaine. Most of the rest tested positive for either marijuana (which remains in urine for weeks) or alcohol. ↩

-

15

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Source-book of Criminal Justice Statistics 1991 (Government Printing Office, 1992), p. 473. ↩