1.

The blues, a form of music that seems as ancient as the emotions it conveys, is actually less than a hundred years old. Sometime in the mists of the late 1890s, somewhere in the South, some unknown singer (or singers) first settled on the now-familiar three-line verse, with its AAB rhyme scheme and its line length of five stressed syllables, e.g.:

Hitch up my pony, saddle up my black mare,

Hitch up my pony, saddle up my black mare,

I’m gonna find a rider, baby, in the world somewhere.(Charlie Patton, “Pony Blues”)

Although the term “blues” came to be applied to any minor-key lament—in the 1920s and 1930s to almost any kind of song—the authentic blues songs are those that hew to this structure. While the sentiments, chord progressions, vocal and instrumental styles that came to distinguish the blues were all lying at hand in the black musical culture of the South, the form itself is just too specific not to have had a very particular origin. All we know of this origin is the result of a process of elimination. For one thing, the folk-song collectors who were already assiduously combing the country in the last quarter of the nineteenth century did not gather any works fitting the blues pattern until after 1900. Even more telling are the accounts of primary encounters with the blues left by black musicians who went on to become so identified with the music as to be credited with inventing it.

In 1903, W.C. Handy, dozing in the depot in Tutwiler, Mississippi, while waiting for a train that was nine hours late, was awakened by a ragged black man playing “the weirdest music I had ever heard,” fretting his guitar with a knife to produce an eerie, sliding wail, and singing about “goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog,” i.e., matter-of-factly describing his impending journey to Moorhead, Mississippi. A year earlier Ma Rainey was working a tent show in Missouri when “a girl from town” turned up to sing a “strange and poignant” song that galvanized the audience. When asked what kind of song it was, she said, “It’s the Blues.” Around the same time or a bit earlier Jelly Roll Morton, in New Orleans, heard a piano player and sometime prostitute named Mamie Desdoumes sing a lament that was clearly a blues:

I stood on the corner, my feet was dripping wet,

I asked every man I met…

Can’t you give me a dollar, give me a lousy dime,

Just to feed that hungry man of mine…

So often depicted as having seamlessly evolved from field hollers and beyond that from griot songs, the blues was actually a sudden and radical turn in African-American music. This is not to say that it materialized in a vacuum. Numerous strains of black folk music were current in the nineteenth century, from field hollers and ring chants to ballads and breakdowns, each leaving some mark on the blues, in lyrics or instrumentation, and many of them were carried on in the twentieth century alongside the blues, by the same musicians. Even “the blues,” the term itself, was not unique to the blues. It may have derived from an Elizabethan term for depression, “the blue devils,” and as a musical designation it existed at least as early as 1892, when Handy first heard “shabby guitarists” in St. Louis singing the song he baptized “East St. Louis Blues,” not a blues in structure but a proto-blues by virtue of its theme and chords, and one that, to add to the confusion, was subsequently recorded dozens of times over the years under nearly as many names: “Crow Jane,” “Sliding Delta,” “One Dime Blues,” “Red River Blues,” “Jim Lee Blues.”

Residing in the same itinerant songster’s bag a century ago might be such equally anonymous foundation stones of American popular music as “Hesitation Blues” (also not actually a blues), “Alabama Bound” (likewise known under a dozen or more names), “Salty Dog,” “C.C. Rider,” “Stavin’ Chain,” “Boll Weevil,” “Spoonful,” “Careless Love,” “Frankie and Albert” (or “Frankie and Johnnie”), “Stagger Lee,” “Poor Boy Long Ways from Home,” “Gang of Brownskin Women,” “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It,” and “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor.” The origins of nearly all of these are lost to history (although “Stagger Lee,” a version of which appears in the Library of America’s American Poetry: The Nineteenth Century, can be traced to an incident that occurred in Memphis in 1890 or thereabouts).1 These songs were carried from place to place by numerous hands, and accordingly altered, extended, abridged, and transposed, but each of them was also written by one or two people at a specific time and place.

Certain old popular songs have so infiltrated the collective unconscious that it may not seem as if they were ever actually composed, but rather that they mysteriously occurred, the way jokes and proverbs sometimes seem as if they had fallen from the sky. The oldest and most durable elements of popular culture defy our notion of authorship, somehow suggesting a prehuman origin. There are, of course, true examples of collective creation, as when melody and lyrics come hurtling at each other from different directions, maybe different traditions, and join through some mysterious agency that may resemble destiny. And there are also works, even in our own time, which despite possessing a known author and point of origin are so altered by a succession of interpreters as to exist almost in fluid form, as a constantly changing entity.2

Advertisement

But then there are also songs whose creation took place in the darkness of poverty and segregation and illiteracy, especially in the time before recordings, and whose authorship is assigned to “Trad.” by default. This is so much the case with black music before 1920 that the exceptions are startling. The early history of jazz may be better documented than that of the blues or its analogues, but it is no less surprising to come upon such definite and exact statements as Sterling Brown’s assertion that the elemental “Shimmy She Wobble” was written by Professor Spencer Williams to celebrate the entertainments of Lulu White’s bordello, or E. Simms Campbell’s claim that “Tarara Boom Dee-ay” was composed in Babe Connors’s house in 1894.3

The origin of the blues occurred close to our time, within a historical corridor that makes it possible to place it among the early manifestations of modernism—between the automobile and the airplane, and not long after the movies, radio transmission, and cylinder recordings—but also in an inaccessible back street of history, so that we don’t know who or when or how or why, just that it happened. Whoever first made up a blues assembled a number of elements at large in the black musical culture of the time, from the flatted intervals to the instrumental accompaniment to bits and pieces of lyrics, quite possibly, and put them together in a way that was not only new, but immediately reproducible as a form. It had the flexibility to yield itself to various kinds of originality, but the strength to remain itself in the process. The blues is at once a musical category as capacious as jazz or rock ‘n’ roll, and a form as circumscribed as the tango or the samba. The former aspect may suggest a gradual evolution over time and by many hands, but the latter pins it down to a particular occurrence. As Samuel Charters, whose The Country Blues (1959) was the first book on the subject, puts it in his essay in Nothing But the Blues: “It is always important to emphasize…that there was no sociological or historical reason for the blues verse to take the form it did. Someone sang the first blues.” Of this inventor’s particular identity we possess not a whisper, not a hint, and we likewise have no idea whether the blues was initially rural or urban, or in what Southern state it originated. No recording of a genuine blues was made until Mamie Smith’s “The Crazy Blues” was waxed in 1920, by which time the music had spread to every hamlet in the black South (and extensive recorded documentation had been made of, say, the polka). By the time it occurred to anyone to ask the question, the trail was cold.

There are many reasons why it was. Not only were the early blues musicians mostly illiterate, they were also mobile, and unpredictable in their traveling patterns. And they were disreputable, the places where they played unsavory—jazz may have emerged from the brothels of New Orleans, but its instrumentation lent it the kind of institutional gravity that mere guitars could not achieve. The blues was fleeting, transient, if not actually furtive. Blues musicians were also fiercely competitive, and loath to acknowledge influence. And, perhaps most importantly, the first researchers with an interest in the origins of the blues did not especially concern themselves with the question of authorship.

John A. Lomax and his son Alan were not the first song collectors to travel through the South with recording equipment, but they were without any doubt the most influential. Starting out in 1933, when Alan Lomax was seventeen, they recorded a breathtaking variety of work songs, game songs, barrelhouse songs, field hollers, ballads, reels, and blues, working under the auspices of the Library of Congress, which not only preserved these works but lent its formidable sanction to the idea that American folk music was at least as much black as it was white. The Texan Lomaxes were at ease with both races, and thus they were able, often but not always, to talk their way into prison farms, plantations (large agricultural estates maintained as private fiefdoms farmed by sharecroppers who were kept in permanent debt), and the like, institutions that extended the premises of slavery and kept their black inmates isolated and unheard. Their work started not a moment too soon, because the 1930s was the very last time when there would be a significant body of folk music at large that had developed without the influence of radio, recordings, or sound films. They were thus able to corral numerous specimens of vanishing breeds, such as black country musicians who employed banjos, fiddles, and accordions, and played a kind of music that for most of the twentieth century would be exclusively identified with whites.

Advertisement

Many of the artists the Lomaxes recorded were farmers or prisoners or road-gang workers or migratory street-corner entertainers, and the recordings constitute all that is known about them. But the Lomaxes recognized a major artist when they heard one, and they brought a number of them to light, beginning with Huddie Ledbetter, aka Leadbelly, whom they first met in 1934, when he was an inmate of the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, doing six to ten for assault with intent to kill. Leadbelly had a penetrating voice, played driving twelve-string guitar, and possessed a huge repertoire that covered nearly every aspect of black popular music. He was, as he later came to be called, a “people’s jukebox,” and along with his memory for the songs, he commanded the lore that went with them and the context in which to situate them—he was, in short, the ideal folklorists’ informant. But he could also draw on the tradition for songs of his own, and upon his release from prison was able to parlay his performing skills into a commercial career with increasing success until his death in 1949. Leadbelly was not an innovator but a particularly protean latter-day songster. He was not especially a bluesman, either, although he had a number of blues songs in his repertoire, having spent time in Dallas in the 1920s playing with the blues pioneer Blind Lemon Jefferson. Leadbelly was, in other words, a folk musician, one who gathered, extended, and disseminated songs from a living tradition.

But could the blues truly be said to be folk music? The Lomaxes simply assumed that it was, and proceeded with their researches accordingly. Alan Lomax’s recent book, The Land Where the Blues Began, exemplifies this assumption. For Lomax the blues is primarily a collective expression, with a core of African music bent and shaped by the pain of slavery, of peonage, of prison, of Jim Crow. This account is not untrue, of course, but it has an obvious limitation. As Samuel Charters writes, “It is always difficult to resist the temptation to continue to look for social influences instead of the individual performer behind the development of the blues.” If the blues materialized so recently, suddenly, and specifically, it seems at best sentimental to attribute it broadly to The People. For Stephen Calt and Gayle Wardlow, the contentious biographers of the radical blues innovator Charlie Patton, the notion of a “blues tradition” is an affront. The Mississippi Delta blues, they point out, lasted as a vital form for less than sixty years, hardly long enough for a tradition to develop. Furthermore,

The rejection of blues by what former jukehouse owner Elizabeth Moore termed “good people” …illustrates that blues had no standing as “folk music,” unless one takes the position that respectable blacks formed a socially deviant element of black society during the blues era.

Part of the confusion, they suggest, derives from the fact that there is in the blues a great deal of collective material, especially in the lyrics—phrases and couplets and entire verses that migrate from song to song, sometimes without obvious relevance to the balance of the lyrics, sometimes indeed deriving from pre-blues sources. This is in fact an element of oral tradition, but this aspect of the blues leads to a false syllogism:

Blues singers play collective material.

Folk musicians play collective material.

Therefore, blues musicians are folk musicians.

For Lomax, the essence of the blues is pain, and as such the form is merely a particular organization of the field holler or the levee-camp holler. He offers a personal illustration:

As a youngster, I tried to sing whatever we recorded, with varying success, of course, but I could never do a “holler” to my own satisfaction. I tried for years and finally gave up. Then came the moment when a holler spontaneously burst out of me. It was the evening of the day I had just been inducted into the army…. When I had been yelled at, put down, examined, poked at, handled like a yearling in a chute, I drew KP. It was a sixteen-hour assignment…. I had never been so miserable in all my life, and there were still two hours to go. At that moment, without thinking, I let loose with a Mississippi holler.

Wondering why this should be, he recalls Leadbelly saying, “It take a man that have the blues to sing the blues.” Lomax divides bluesmen into two camps, those from stable families and those from broken homes—their vocal styles give away their origins. Listening to Sam Chatmon, a former member of the Mississippi Sheiks and one of the large and talented clan that also produced Memphis Slim (Peter Chatmon) and Bo Carter (Bo Chatmon), among others, he writes:

He sang about the bitterness of Delta love in a rather matter-of-fact voice, without either the keening of a Robert Johnson, the ironic merriment of Eugene Powell or Papa Charlie Jackson, or the rage of Son House. Perhaps he was too old to care, but I suspect that because he came from this stable family background, the anguish of the blues did not touch him as deeply as it did others.

He comes to a similar conclusion about Muddy Waters (né McKinley Morganfield), whom he was the first to record, in 1941 (“He learned to play the guitar only three years ago, learning painfully, finger by finger, from a friend,” say the original liner notes). He doesn’t disparage Muddy, but suggests that his “relaxed, rich vocal style” lies some distance away from the shrieks of those abandoned early in life. This index of misery is a commonplace that nearly everyone associates with the blues. It dates back at least to W.C. Handy’s account of composing the “St. Louis Blues”:

While occupied with my own miseries during that sojourn, I had seen a woman whose pain seemed even greater. She had tried to take the edge off her grief by heavy drinking, but it hadn’t worked. Stumbling along the poorly lighted street, she muttered as she walked, “Ma man’s got a heart like a rock cast in de sea.”

The expression interested me, and I stopped another woman to inquire what she meant. She replied, “Lawd, man, it’s hard and gone so far from her she can’t reach it.”… My song was taking shape. I had now settled upon the mood.4

Handy set down this version of events in his autobiography, Father of the Blues, published in 1941. Closer to the date of the song’s composition (1914) he had however written, “The sorrow songs of the slaves we call Jubilee Melodies. The happy-go-lucky songs of the Southern negro we call blues.” Calt and Wardlow believe that the despair quotient in the blues was Handy’s invention, later taken up by Tin Pan Alley songwriters producing generic blues. As an example they contrast an early lyric of Charlie Patton’s:

Gonna buy myself a hammock, gon’ carry it underneaththrough the tree

So when the wind blow, the leave[s] may fall on me

with a commercial product of slightly later vintage:

Got myself a brand new hammock, placed it underneath a tree

I hope the wind will blow so hard the tree will fall on me.

Somehow, though, all attempts to make categorical statements regarding the blues wind up seeming reductive. It is important to consider both the richness of the blues songs that have come down to us, and the haphazard nature of their means of transmission. For all the brilliance of the early blues as they exist on record, an unknown quantity of performers and songs at least equally brilliant were never recorded, and even their rumor has not survived. Most writers on the blues, beginning with Charters, have for example simply assumed that the blues was born in the Mississippi Delta. But this deduction is based on little more than the fact that an unusually high number of exceptional performers came from there. According to Stanley Booth’s elegiac Rythm Oil:

If you describe on a map a circle with its center at Moorhead, Mississippi, the place where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog, lying within a hundred-mile radius are not only Como and Hernando, but also Red Banks, Helena, Lyon, Leland, Rolling Fork, Corinth, Ruleville, Greenville, Indianola, Bentonia, Macon, Eden Station, West Point, Tupelo, Tippo, Scott, Shelby, Meridian, Lake Cormorant, Houston, Belzoni, Bolton, Tunica, Yazoo City, Lambert, Vance, Burdett and Clarksdale, whence come Gus Cannon, Roosevelt Sykes, Son House, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, Fat Man Morrison, Charlie Patton, B.B. King, Albert King, Skip James, Bo Diddley, Emma Williams, Howlin’ Wolf, Elvis Presley, Mose Alison, Big Bill Broonzy, Willie Brown, Jimmie Rodgers, Robert Johnson, Bukka White, Otis Spann, Bo Carter, James Cotton, Tommy McClennan, Jasper Love, Sunnyland Slim, Brother John Sellers, and John Lee Hooker.5

“Among others,” he might have added, since this prodigious list is equally striking in its omissions (Memphis Minnie, Elmore James, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Big Joe Williams, Big Boy Crudup, Robert Nighthawk, Johnny Shines, and both Sonny Boy Williamsons, to name a few). Nevertheless, there is no proof the blues began within this circumference, no matter how rich the musical soil. The circle, which takes in a good third of the state of Mississippi and chunks of southeastern Arkansas and northeastern Louisiana, is entirely rural, excluding Memphis, Tennessee, by fifteen or twenty miles. But the blues might well have been urban in origin. Earlier than Handy’s first hearing of the blues in Moorhead were Ma Rainey’s, near St. Louis, and Morton’s, in New Orleans. The indefatigable Calt and Wardlow interviewed scores of Delta old-timers in the 1960s and were unable to find any who recalled hearing the blues before 1910. A plausible scenario: the blues was born in New Orleans, where it was only one of a number of competing marvels. Eclipsed by the success of jazz, it came into its own in the country, where it lent itself naturally to juke joints and guitars, ad hoc venues and portable instruments.

Urban blues, in the 1920s more accurately known as vaudeville blues, were the first to be recorded, and they were most frequently sung by urbane and knowing women, most of them young. The received idea that these blues were somehow slicker and less authentic than the rural sort merely reflects a provincial bias, perhaps originating with white beatnik enthusiasts in overalls. It is also true that the Delta is rivaled for fecundity in the earliest times that we know of by east Texas and western Louisiana. Could the blues have begun in two places at once? Blind Lemon Jefferson, arguably the most influential blues guitarist of the 1920s, was Texan, as was Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas, born in 1874 and thus the oldest known blues singer to have recorded. Others who owed nothing to Mississippi included the scary, rasp-voiced gospel bluesman Blind Willie Johnson, the primordial moaner Texas Alexander, and the wild King Solomon Hill, as rhythmically unfettered as any blues singer ever was.

For that matter, a distinct chapter in the history of the blues’ transmission would concern sawmills and turpentine camps throughout the forests of the deep South, settlements featuring barrelhouses, whose upright pianos engendered a particular style of keyboard blues that led directly to boogie-woogie. Nevertheless, the story always seems to come back to Mississippi. There is no denying that, from the middle Teens to the late Forties, the northwestern quadrant of that state saw an astonishing conjunction of original talents amid surroundings that are at best unprepossessing. A wayside like Drew or Robinsonville begins to sound like Paris in the same period. Four of the five books considered in this essay are primarily concerned with the mystery of the Mississippi Delta. None of them solves it, of course, but they all contribute to deepening it.

2.

Robert Johnson may be the most mysterious of all the Delta blues artists. He died in 1938, at the age of twenty-six, leaving behind forty-one recordings, twenty-nine different songs, and alternate takes. Little is known about him; even his surviving contemporaries, friends and traveling companions, describe him in generalities. He was shy, footloose, aloof maybe, neurotically concerned with hiding his hands when playing if other guitarists were around—this stands out. He comes late enough in the blues genealogy that his influences can be traced, and they range from one end to the other of the recorded blues of his time.

He was somehow both obscure and legendary in his own lifetime. The story was that he was an adolescent nuisance hanging around older musicians, banging around ineptly on their instruments when they set them down; then he went away for a while and came back a phenomenon. It was noised about that he had made a pact with the devil, but that was the same story that had been circulating concerning the older and unrelated (and very different) Tommy Johnson, so that it was either misheard or possibly Robert’s own press agentry. He played juke joints and street corners in places that ranged all the way to Chicago and New York City, traveling on freights and by hitchhiking. His big break came when the promoter John Hammond sought him out for his “From Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall in December 1938, intending to present him as the first Delta blues singer to appear before a white, big-city crowd, but unfortunately he had been murdered several months earlier. By the time the first LP of his songs came out, in 1961, the situation could be summed up by Frank Driggs in his liner notes: “Robert Johnson is little, very little more than a name on aging index cards and a few dusty master records in the files of a phonograph company that no longer exists.”

There is a little more now, but not a great deal—Peter Guralnick’s measured and honest small book contains, in sixty-eight pages not counting bibliography, just about everything, or at least everything that’s been brought to light. This does not include the name of his murderer, who was evidently last seen in Key West in 1975, or the one of the three known photographs of Johnson that has never been made public. The pictures weren’t found until 1972 and were promptly copyrighted by a researcher; two of them were finally published fifteen years later, in Rolling Stone and 78 Quarterly, respectively. In the meantime, Robert Johnson captured the imagination of the world. His Complete Recordings won a Grammy in 1990, and the set is presumably owned by many people who have no other acquaintance with acoustic blues.

He is esteemed for his influence on rock ‘n’ roll, to be sure (the Rolling Stones recorded his songs “Love in Vain” and “Stop Breaking Down”), and for his function as a sort of historical funnel (reflecting what went on in blues before him and anticipating much that would happen after his death), but it is the intertwining of his art and his enigma that makes him indelible. It is hard to separate one from the other. During his lifetime he was best known for “Terraplane Blues,” an extended car-as-sex metaphor (and thus a progenitor of a durable American pop-culture motif), and his performance repertoire apparently included Bing Crosby numbers, hillbilly yodels, novelty songs, “My Blue Heaven.” The songs for which he is remembered, though, are devil-haunted, death-obsessed. His lyrics seem to bear out the rumor of his demonic pact and foretell his shadowy end (he was poisoned by a jealous husband):

If I had possession over judgment day

If I had possession over judgment day

The little woman I’m lovin’ wouldn’t have no right to pray

and

You may bury my body down by the highway side

You may bury my body down by the highway side

So my old evil spirit can catch a Greyhound bus and ride

and

I got to keep on movin’

I got to keep on movin’

blues fallin’ down like hail

blues fallin’ down like hail

And the days keeps on worryin’ me

there’s a hellhound on my trail

hellhound on my trail

hellhound on my trail

Not that the words can really be set apart from Johnson’s timing and his guitar, the alternating growl and sigh of his delivery, the fatalistic way he echoes his lines. In his book Mystery Train, Greil Marcus—who says he finds Johnson the appropriate background music for reading Jonathan Edwards—portrays Johnson as inheritor of the Puritan devil, “the Puritan commitment to extremes, the willingness to live in a world where the claims of God and the devil are truly at odds.”6 This Manichean tension shows up often in American popular music both black and white, a significant element in the lives and works of, for example, Ray Charles, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Hank Williams. But these artists all belong to a later era, and all must have been somehow informed by Robert Johnson, who was the first to be explicit about the duality. Johnson was a startling blues poet, a wrenching performer, an eclectic and elastic guitarist whose playing sometimes, in Marcus’s words, “sounds like a complete rock ‘n’ roll band,” and he was also a figure who despite his brief life and meager recorded output managed to embody the spirit and the contradictions of the blues. He is the landscape’s most redoubtable ghost.

His ghostly presence, meanwhile, has been magnificiently rendered in Alan Greenberg’s film script, Love in Vain. First published in 1983 and reissued apparently in anticipation of Martin Scorsese’s screen production, this is no mere biopic. As difficult as it is to depict the life of an artist in movie form without tumbling headlong into ridiculousness, Greenberg has done it by, first of all, not attempting to explain anything. His Johnson is a changeling, flesh-and-blood but mutable and secretive, and he dwells in a world of workaday magic, where his meeting with the devil takes place at the moviehouse in front of a western, and where Charlie Patton’s funeral turns into a ferocious soul-claiming contest between Johnson and the Rev. Sin-Killer Griffin.

Greenberg not only evokes Johnson in a way that actually enlarges our view of him, he also depicts the blues world of the time, from Mississippi to Texas, in all its variegated splendor and misery. He makes a point of bringing in the most original and singular musicians, from the flamenco-inflected Buddy Boy Hawkins to the sublime gospel hymnist Washington Phillips, and he ranges beyond music to include a great range of the voices of the black South: chanting street vendors and train callers, itinerant preachers, German-speaking black cowboys in Texas. Through details and suggestions, he succeeds in showing both how this rich culture fed Johnson, and how Johnson assimilated it and transcended it. The screenplay is also much more accessible to the reader than scripts usually are, and it comes with fifty pages of instructive and absorbing notes.

The search for Robert Johnson was also the initial point of departure for the series of expeditions into the Delta that Alan Lomax describes in The Land Where the Blues Began, and he gives a moving account of hearing the sad news of Robert’s death, in Bogalusa, Louisiana, from his religious ecstatic of a mother, Mary Johnson, at her shack in Tunica County. Unfortunately, Johnson’s mother’s name was Julia Dodds, and he died outside Greenwood, Mississippi. There is also some confusion about the timing: Lomax implies that John Hammond put him on to the search, but the recording trip seems to have taken place in 1941, by which time most interested parties knew of Johnson’s death. The point may seem academic, but the muddle is not untypical of Lomax’s book, which despite its many virtues is permeated by a haze of factual uncertainty.

He repeats, for example, the old canard that Bessie Smith bled to death in the wake of a car crash after having been denied admission to a white hospital (in fact, no ambulance driver would have taken a black person to a white hospital in Mississippi in 1937; she died of shock in the Afro-American Hospital in Clarksdale). Perhaps it is that the deaths of blues musicians are particularly subject to dubious or imaginative retelling; Lomax quotes Big Bill Broonzy on Blind Blake, who he says slipped and fell late at night during a blizzard in Chicago “and, by him being so fat, he couldn’t get up and he froze to death before anybody found him.” But the only extant photograph of Blind Blake shows him looking rather trim, and the blizzard-demise tale is usually told about Blind Lemon Jefferson, who is fat in the only picture we have of him. In any event, no documents have ever been found concerning the death of either man.

Lomax may not have found Robert Johnson, but he did find the young Muddy Waters, whom he recorded in an important series of performances on Stovall’s Plantation near Clarksdale in 1941 (and who would go on to Chicago and the invention of the electric blues later in the decade), and through him he found Son House, who had known and traded licks with both Johnson and Charlie Patton. But while he thus had a pipeline on the most important strain of the Delta blues, Lomax was perhaps more interested in the work songs and ring chants, the African survivals in the black music of the South. Although many well-known names crop up in the book—Lomax was also the first to record Fred McDowell and David “Honeyboy” Edwards, and in 1946 he taped an extraordinary session in which Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson talked frankly about racial oppression and its role in the music—the narrative is more concerned with the anonymous many who sang part songs while hoeing rows as convicts on Parchman (prison) Farm, or hollered for the benefit of their mules while building levees, or entertained their neighbors in obscure back-country settlements without any thought of recording the songs they made up. His populist faith is absolute, and while it can sometimes have a leveling effect, making the deliberate decisions of innovative artists indistinguishable from the inherited or instinctive moves of people following tradition without questioning or altering it (and here we get back to the “folk music” debate), there is no denying the power of what it led him to find.

But then he was combing the Mississippi Delta and its surrounding hills. Lomax’s view on the origin of the blues is shared widely, even by those who, like Samuel Charters, insist on the role of a single innovator. The blues had to have begun in Mississippi, they claim, because for complex and not altogether explicable reasons that state retained more unassimilated African traditions than any other part of the country. These include dietary, linguistic, and domestic matters (such as the survival of the raked dirt yard), but the amount of musical culture is staggering. As recently as the 1960s, Lomax and others were turning up previously unsuspected vestiges of ancient traditions. Among these were the use of pan-pipes (called “quills”) and the significance of fife and drum bands in the culture of the state’s arid hills. Lomax’s primal scene for the blues, however, involves the Delta-based conjunction of two other phenomena: the holler and the diddley bow, a single-stringed instrument that can be assembled quickly and mounted on any surface, including the side of a house, making the whole house its resonator. It is not difficult to hear that vocal style and that instrument in the chilling wail and slide guitar of Son House’s “Death Letter,” for example, or even in an electric, full-band piece like Howlin’ Wolf’s “Moanin’ at Midnight.” The holler and the diddley bow do not constitute the blues, but they are at least its table setting.7

Charlie Patton’s biographers, Calt and Wardlow, are singularly unimpressed by the search for the deep origins of the blues and seem to view as sentimental any approach to the music that is geared to anything but individual talents. They do not mince words. John A. Lomax, they write, was “obtuse and unimaginative,” an “ideologue” whose researches were determined by his “idee fixe…to document the survival of the ‘field holler’ and work song.” They judge Lomax Sr.’s spending four days recording convicts at Parchman Farm in 1933, while ignoring Patton, who was still alive nearby, to have been the height of irresponsibility. To appreciate their indignation in context it is important to realize that we are lucky to have any recordings of Patton, or of any other early blues artist, at all. The first wave of recordings of Delta musicians does not precede 1927, peaks around 1929, and gradually peters out during the early years of the Depression. The commercial recordings made by black Mississippians during this period were made possible by just two men, the only two talent scouts in the state who took any interest in the blues, Ralph Lembo of Itta Bena and H.C. Speir of Jackson. There is no question that each possessed an exceptional ear, and that Speir in particular took extraordinary chances on difficult and unobvious talents, but nevertheless the potential for artists to slip through the cracks was large.

The recording companies presented their own set of obstacles. Country blues records were generally intended for sale only to black people in the South, and they were not engineered, manufactured, or marketed with the greatest care. One of the chief producers of “race” records in that period was Paramount, a division of the Wisconsin Chair Company of Port Washington, Wisconsin (and no relation of later companies bearing the same name). The Wisconsin Chair Company went “race” only because the sound quality of its records was so inferior that white record store owners would not stock them. The records were so cheaply made that they would sometimes wear out after just fifty plays; at the then-exorbitant price of 75å¢ a throw this was a thankless proposition. Small wonder, then, that the records have become such rarities. Since unsold records were destroyed, only the very biggest hits have survived in appreciable numbers. Numerous are the legendary sides known today only as listings in company catalogs. Only one copy is known to exist of a major Son House number, “Preachin’ the Blues,” and its condition is so bad that even on digitally remastered CDs it is barely listenable.

Charlie Patton was sufficiently popular in his own time that all the records that were issued under his name have survived in at least one or two reasonably good copies. The unissued titles, however, are gone forever, as are the master recordings, so that what we are left with is the equivalent of a great painter’s entire corpus being known exclusively through black-and-white photographs. And Patton, scarcely a household word even these days, was without question a great artist, a fully conscious experimentalist and a highly sophisticated formal innovator, a genuine modernist despite the fact that he hardly ever lived outside plantations in Sunflower and Bolivar counties, Mississippi. His life was both hectic and constricted:he played music, took up with women, got into fights, migrated around a patch of the Delta. He survived having his throat slit at a house frolic in 1933, only to die of heart failure the following year, at the age of forty-three. He was tremendously influential—nearly every Delta bluesman of the Twenties and Thirties attempted some variation on his “Pony Blues”—but for all that inimitable. Among his breakthroughs:

He was seemingly the only blues guitarist of the age who could completely rearrange material. He recorded the only blues song (Screamin’ and Hollerin’) with a basically improvisatory melody, the only dance blues without a constantly repeating melody (Pony Blues), and the only dance song that had appreciable instrumental variations (Screamin’ and Hollerin’, with its three bass lines).

His singing sounds rough, unpolished, except on the numbers where he nearly croons, so that the roughness had to have been deliberate. He enjoyed turning out variations on the blues trick of making the guitar take over the vocal part. According to a contemporary: “He had one piece he used to play a stanza out of every song he played, each song; put it together, and make a song out of that”—i.e., he constructed a song from fragments of his repertoire. Patton was an entertainer at house frolics and juke joints, remembered by some of his contemporaries chiefly for his “clowning,” playing the guitar behind his back or over his head, if not for his propensity for getting in trouble, getting thrown in jail, getting ejected from plantations, and yet as an artist he made dense, intricate, difficult work.

Calt and Wardlow are appropriately tough in their defense of Patton. They are alert to the many reductive ways Patton has been or can be lumped or dismissed or even praised. They will simply not accept any guff about his having been a folk musician, part of a tradition, a participant in collective creation, etc. They have done the research, invested the legwork, subjected the evidence to analysis, refused to indulge in airy generalities. Unfortunately, they also seem to feel that Patton cannot be given his due without every other Delta musician being correspondingly brought down several pegs. Perhaps none was the equal of Patton, but all have their value: Tommy Johnson had a delicate, sinuous delivery with a hypnotic edge; Son House was intense, passionate, single-minded; Skip James was simply ineffable, suggesting his structures with the most minimal strokes; Howlin’ Wolf’s voice was, in the words of Sam Phillips, “where the soul of man never dies.” All of them are variously dissed by Calt and Wardlow; Wolf is called a “parasite.”

Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett) is the outside man in this series, the late bloomer. A contemporary of Robert Johnson’s and a resident of Dockery’s Plantation, where Patton spent much of his life, Wolf farmed with his father until he was nearly forty. He moved north not long after becoming a professional musician and came into his own in Chicago in the 1950s. For others, the spin of the Delta policy wheel was not as fortunate. Patton died of heart failure at forty-three. Tommy Johnson hung on until the age of sixty despite a bad drinking problem, but never recorded again after the early 1930s. Skip James and Son House both disappeared from view, James after a single recording session in 1931, House after having been lost and found a couple of times. Both were tracked down by enthusiasts in the 1960s and along with a number of other elderly blues artists were able to ride the fads of that era and live out their lives as professional musicians. Many others are just names, such as the leading musicians of the generation before Patton: Henry Sloan, D. Irvin, Mott Willis, Cap Holmes, Jake Martin, Jack Hicks; or Robert Johnson’s teacher Ike Zinneman. Or there are those who recorded only three or four sides, which hint at things we’ll never know: Garfield Akers, Rubin Lacy, William Harris, Elvie Thomas, George “Bullet” Williams, Louise Johnson, Freddie Spruell, Kid Bailey.

The 1960s came too late for them. For those aged blues musicians who benefited from the revival, the experience must have nevertheless been disconcerting. When a collector showed up at the house of Mississippi John Hurt in 1963, saying, “We’ve been looking for you for years,” Hurt, who thought his visitor was an FBI agent, said, “You got the wrong man! I ain’t done nothing mean.” The Sixties revival came about as a result of the conjunction of the civil rights movement, the coffeehouse folk scene, and the efforts of a generation of enthusiasts, particularly the collectors who canvassed door-to-door in black neighborhoods in the South, looking for rare Gennett or Black Patti or Paramount 78s. Half of the books considered here are direct products of that tendency—Calt, Wardlow, and Lawrence Cohn (whose Roots and Blues reissue series on CBS/Sony draws heavily on his personal collection of 78s) were especially prominent in blues-connoisseur circles of the 1960s. The books benefit from the passion and the scholarship that the collectors brought to their pursuit, but at least in the case of Calt and Wardlow they do not altogether avoid the thirst for ownership prevalent in that crowd.

Calt and Wardlow’s defense of Patton against all comers is understandable, given his true stature and the neglect and distortion his reputation has suffered, but their monomania begins to sound proprietary. If they were writing about a Romantic poet or a Surrealist painter it would sound just as proprietary, but here there is no getting away from the fact that they are whites writing about a black figure, marginal in his own day. Of course, all these books were written by whites; the amount of black writing on the blues is minuscule, and the few pieces that come to mind, by Albert Murray or Sterling Brown, for example, are mostly concerned with jazz. Even Amiri Baraka’s Blues People has little to do with the blues per se (it is a tract, from the perspective of the early Sixties, on the sociology of black music). The reasons for this absence are complex: the disrepute of the blues in the 1920s and 1930s, the variously rustic, passé, unenlightened, non-progressive tinges it acquired later on, at least in the eyes of certain black intellectuals.

The white fascination with the blues, especially the country blues, has always been vulnerable to accusations that it represented a kind of colonial sentimentalism. While perhaps unjust, this notion was certainly borne out by some of the grotesqueries of the 1960s and 1970s, when pimply devotees of “de blooze” misunderstood the music in a colossal way, unable to distinguish between tribute and ridicule. Affected Mississippi accents and pointless guitar noodling were the norm among suburban epigones. “They got all these white kids now,” the ever-generous Muddy Waters told Robert Palmer. “Some of them can play good blues. They play so much, run a ring around you playin’ guitar, but they cannot vocal like the black man.”8 (There were exceptions, of course. The white musicians who did the most honor to the blues were often those, like the great Captain Beefheart, who took the largest liberties with the form.) Other white enthusiasts were, instead, tormented by guilt. In Nothing But the Blues, Bruce Bastin writes: “At the time of the death of the eccentric but undeniably brilliant Guitar Shorty from North Carolina, a friend remarked that she would be glad when she could no longer hear music like his, as it would mean that the social context that gave rise to it was gone.”

In one stroke, this deeply fatuous statement lays bare all the ambivalence that attends the blues in the United States, an ambivalence in which Alan Lomax’s book, in particular, is drenched. If the blues is a form of music based on human suffering, then enjoyment of the blues is tantamount to enjoyment of suffering. The only appropriate attitude for listening, therefore, is guilt. And if the blues is the direct result of the racism of past decades, then it must follow that subsequent forms of black music, indeed of black culture, are likewise the results of racism, since racism has only changed in its manifestations. And if this is so, then black culture is one-dimensional and exists solely in response to white culture.

This is why the apparently academic question of where and when and how the blues began is important. The blues was not a reaction or a spontaneous utterance or a cry of anguish in the night, and it did not arise from a great mass of people like a collective sigh. It was a deliberate decision arrived at by a particular artist (or artists) through a process of experimentation, using materials at hand from a variety of sources. It was taken up by others and expanded to encompass anguish as well as defiance, humor, lust, cruelty, heartbreak, awe, sarcasm, fury, regret, bemusement, mischief, delirium, and even triumph. It grew to be the expression of a people, but not before it had become as diverse and complicated as that people. It, too, ranges beyond the monochrome of its name.

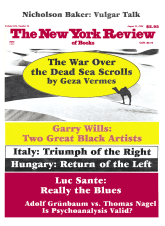

This Issue

August 11, 1994

-

1

For a discussion of the labyrinthine turns in the story of the song and the story behind the song, see Greil Marcus’s Mystery Train, pp. 213-220 in the third revised edition (Plume, 1990). ↩

-

2

An awe-inspiring recent example of this phenomenon is charted in great detail and lively fashion by Dave Marsh in Louie Louie: The History and Mythology of the World’s Most Famous Rock n’ Roll Song; Including the Full Details of its Torture and Persecution at the Hands of the Kingsmen, J. Edgar Hoover’s F.B.I., and a Cast of Millions; and Introducing, for the First Time Anywhere, the Actual Dirty Lyrics (Hyperion, 1993). ↩

-

3

Brown, “Basin and Rampart Street Blues,” in Sidewalks of America, edited by B.A. Botkin (1954), pp. 153-154; Campbell: “Early Jam,” in The Negro Caravan, edited by Sterling Brown (Dryden Press, 1941), pp. 983-990. ↩

-

4

Father of the Blues (Da Capo, 1970), p. 119. ↩

-

5

Stanley Booth, Rythm Oil: A Journey Through the Music of the American South (Vintage, 1993), p. 39. ↩

-

6

Marcus, Mystery Train, pp. 30-31. ↩

-

7

Lomax’s field recordings of the 1940s and 1950s have been reissued in a multi-CD box as Sounds of the South by Atlantic Records, 1993. ↩

-

8

Robert Palmer, Deep Blues (Penguin, 1981), p. 260. This is still the best general history of the Mississippi Delta blues. ↩