In 1957 the English social critic Richard Hoggart published The Uses of Literacy, subtitled Aspects of Working-Class Life, with Special Reference to Publications and Entertainments. His aim was to describe modern English working-class culture on the evidence of his own experience and of the materials, printed or not, devised for the instruction and diversion of that class. His conclusions were measured:

My argument is not that there was, in England one generation ago, an urban culture still very much “of the people” and that now there is only a mass urban culture. It is rather that the appeals made by the mass publicists are for a great number of reasons made more insistently, effectively and in a more comprehensive and centralised form today than they were earlier; that we are moving towards the creation of a mass culture; that the remnants of what was at least in parts an urban culture “of the people” are being destroyed; and that the new mass culture is in some important ways less healthy than the often crude culture it is replacing.1

Hoggart was especially familiar with the working-class communities of Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield, and Hull. He made no particular reference to Scotland, presumably because he thought the differences between working-class life there and in England were slight.

If James Kelman’s novels and stories are taken as evidence, Scotland, or at least Glasgow, deserves a separate chapter in such a book as Hoggart’s. The mass urban culture that Hoggart dreaded has arrived in Glasgow’s Sauciehall Street, the Gorbals, Crown Street, Cumberland Street, and Scobie Street. Kelman’s characters are working-class people, even though most of them are out of a job and living on the dole. They remember what it was like to work, however irregularly, or at least what it was like for their fathers to work. In Kelman’s A Disaffection (1989) the main character, Pat Doyle, is a teacher and he has a job, but he identifies himself with the working class, rages against the social and political system, and despises himself for playing a middle-class part in it. He assumes that “the system” is in place, permanently, and that it is represented now and forever by its deadly bureaucrats.

In Kelman’s most recent novel, How Late it Was, How Late, the hero, Sammy Samuels, lives on the gyro, the Friday check from the Employment Exchange. The book is not a straight-forward narration but a soliloquy by Sammy raging over his dealings with the police, civil servants, doctors, and other exemplars of authority. Although the events are not always clear, we gather that he is back on the streets of Glasgow after doing time in jail—eleven of his thirty-eight years—and is blind as a result of a fight with some soldiers and a beating by the police who arrest him for the brawl. Sammy manages to make his way home from jail in spite of his blindness, only to find that his live-in friend, Helen, has disappeared and that he is under suspicion of having harmed her. Before long he is arrested again, and interrogated about his chance meeting with an old buddy who may be a terrorist; the police think Sammy knows his whereabouts and plans.

Sammy moves from one incident to the next without any plot or pattern emerging. The events mainly have the weight of being arbitrary. There is no sense of Sammy’s life culminating in a purpose or a change of direction. One damn thing merely leads to another in the same distressful form. What we mainly get from Sammy is his certainty that he is in danger, beset by careless doctors and brutal policemen. Like nearly everyone in Kelman’s books, Sammy has cause to be miserable, and is voluble in expressing it.

Kelman was born in Glasgow in 1946. His father was in the business of picture-framing and gilding. According to Kelman’s Some Recent Attacks: Essays Cultural and Political (1992), he regards himself as “a white middleaged Glaswegian atheist protestantbred male writer and father of two mature daughters, who lived his early years in Govan, Drumchapel, Partick, and Maryhill.” His political position is simple: “Nothing was ever given freely by the ruling class.” As for the political parties: a plague on all their houses. He loathes the Conservative Party, and despises the Labour Party as Tories in disguise. Not even the Scottish National Party gets his vote. He evidently agrees with his friend Tom Leonard, who has described members of the SNP as “people whose idea of a liberated Scotland is the Royal Toast given in Lallans.”2 “I have no faith in any political party,” Kelman has written. “A vote for any party or any individual is always a vote for the political system.”

When he refers to his literary work, he never invokes his predecessors or the idea of a tradition: for his purposes, it appears, literature might as well have been invented yesterday. When he started writing, he reports, “there were no literary models I could look to from my own culture.” I think he means that he could not learn anything useful, even from an acknowledged master, Hugh MacDiarmid, or from Sydney Goodsir Smith or Norman MacCaig: these writers were too closely identified with genteel Edinburgh, I imagine. “It was only later on,” Kelman says, “that I had the good luck to meet up with folk like Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead and the critic Philip Hobsbaum.” He refers to the “things I knew about: snooker halls and betting shops and pubs and DHSS offices and waiting in the queue at the Council Housing office.” These or similar experiences turn up in How Late it Was, How Late, A Disaffection, and the short stories in Kelman’s An old pub near the Angel (1973) and Greyhound for Breakfast (1987). How Late it Was, How Late keeps company with Gray’s Lanark and Torrington’s Swing Hammer Swing! as fictions of hard times in Glasgow.3 The dedicatory page in How Late it Was, How Late reads: “Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Agnes Owens and Jeff Torrington are still around, thank christ.”

Advertisement

The main difference between Hoggart’s working-class culture and the culture implied by Kelman’s fiction is a vast increase in anger. What Hoggart called “working-class stoicism” has gone sour, turned to rage, rancor, disgust. Every institution is deemed to be a zone of disaffection. One of Hoggart’s subsections was called “There’s No Place like Home.” In Kelman’s Glasgow, home is the last place you think of going; home and hearth turn you into a malcontent. But there are other causes of spleen. Glasgow resents Edinburgh and hates England, “the Auld Enemy.” “The English are not huffy,” Pat Doyle thinks, “just fucking imperialist bastards.” The US, incidentally, is the ultimate enemy.

One observes the clearest difference between Hoggart’s working class and Kelman’s in the increase in what used to be called “bad language.” Hoggart commented on “the way many working-class men speak when no women are present”:

George Orwell, noting that working-class men use four-letter words for natural functions freely, says they are obscene but not immoral. But there are degrees and kinds of obscenity, and this sort of conversation is often obscene and nothing else, obscene for the sake of obscenity in a dull, repetitive and brute way…To each class its own forms of cruelty and dirt; that of working-class people is sometimes of a gratuitously debasing coarseness.4

In 1957, I gather from Hoggart, fuckwords were not heard in the best-regulated living rooms, as they are now.

Still, Kelman’s language calls for particular description. When How Late it Was, How Late won the Booker Prize last year, many readers and one or two members of the jury protested that every third word in the book is “fuck.” I haven’t counted them, but the proportion of bad language in the old-fashioned sense to good is notably high. Men do most of the swearing, undeterred by the presence of women. Here is a fairly average passage when Sammy finds himself back in jail after Helen has disappeared:

But it couldnay get worse than this. He was really fuckt now. This was the dregs; he was at it. He had fucking reached it now man the fucking dregs man the pits, the fucking black fucking limboland, purgatory; that’s what it was like, purgatory, where all ye can do is think. Think. That’s all ye can do. Ye just fucking think about what ye’ve done and what ye’ve no fucking done; ye cannay look at nothing ye cannay see nothing it’s just a total fucking disaster area, yer mind, yer fucking memories, a disaster area. Ye wonder about these things. How come it happened to you and nay other cunt?

One of the funniest stories in Greyhound for Breakfast, “In with the Doctor,” has doctor and patient swearing with the same degree of fluency. The patient talks like Sammy, but here is the doctor:

Take a look out there, he says, it’s a fucking disgrace. Here I am trying to run a doctor’s surgery and I can hardly get fucking moving for dirt and dust and dods of garbage man blowing in the fucking door every time it gets opened for something I mean Christ sake man you’re talking about that lot ben there!

The bad words here express anger, indeed, but in other passages they don’t convey any strong emotion, they are almost neutral. As in A Disaffection:

He was probably just a big self-conscious fellow who felt he was just too skinny and lanky to be playing professional football, he was all knees and fucking elbows.

Sometimes in A Disaffection they are used to emphasize praise:

Advertisement

Yoker had scored. And what a goal as well according to everybody: their winger had cut in from the right and chipped the ball over the heads of the defence and back to the eighteen-yard line where the striker caught it on the volley and bump, straight into the corner of the net, a fucking beauty.

Many of Kelman’s stories, and How Late it Was, How Late, are told in Standard English, with the addition of a few local words easy enough to construe: bevy (drink), crash (one’s turn to buy a round of drinks), skint (no money: broke), bit (but), broo (the Employment Exchange), yin (one), smash (loose change), cludgie (lavatory), tim (Teigue, an Irishman), and cunt (as in French con, a person, man or woman). Some words in How Late it Was, How Late have defeated me: sindied (p. 126), minging (p. 151), scoosh (p. 58), and bridie (p. 253), but generally the vocabulary isn’t a problem. A few stories, however, are told in demotic Glaswegian: “Nice to be Nice,” the last story in An old pub near the Angel, for instance. Here is a paragraph of that one:

The Anchor wis crowded in A saw auld Erchie staunin near the domino table wherr he usually hings aboot if he’s skint, in case emdy waants a drink—he sometimes gits a drink fir gaun. A wint straight tae the bar is assed Sammy fir two gless a whisky in a couple a hauf pints in whin A went tae pey the man A hid fuck aw bit some smash in a note [nothing but some loose change and a note] sayin “Give you it back to-morrow, Tony.” Forty quid in aw! A’ll gie ye it the morra! Fuckin cheek! Probly oor it Ashfield the noo daen the lot in [probably over at Ashfield now spending the whole lot]. Forty notes! Well well well—in it wisny the first time. A mean he disny let me doon, he’s eywis goat it merr ir less whin he says he wid bit—nice tae be nice—know what A mean? See A gave him a sperr key whin we wir daen up the kitchen in let him hang oan tae it efterwirds kis sometimes he’s nae wherr tae sleep in A let him kip wi me.

That’s not too hard, either, especially if you could get the Scottish comedian Billy Connolly to read it.

But the relation between Kelman’s Standard English and his streettalk—his demotic Glaswegian—is not clear. When I started reading How Late it Was, How Late, I thought he was using Standard English to denote authority and demotic to give Sammy the only freedom he enjoys, freedom of speech. When he wakes up in jail after being beaten up by the police, sparseness and irregularity of punctuation seemed to give Sammy his own rhythm, free of official niceties, grammar, syntax:

Sammy dragged the t-shirt out the trousers to examine the body, letting the screw see he knew the score, like he was making notes for future reference, once he stuck in the auld compensation claim I mean ye cannay go about knocking fuck out of cunts and expect them no to submit their claim through the proper channels, no if ye’re an official servant of the state I mean that’s out of order, banging a citizen.

Or later when a couple of policemen rush him out of his cell one morning and drive him to a doctor’s office:

Fuck the sodjers, nay point worrying about them, they had their own agenda.

But that apparent division of dictions doesn’t hold throughout the book. I now think that the language Kelman gives Sammy, especially the bad language, is designed to relieve him of any possible duty to take a deferential attitude toward objects or events. Sammy’s speech lets him attend to his own desires and gestures: he owes the world nothing, not even the duty of referring to its manifestations as if they had rights. They exist, but so what? That doesn’t do anything for them or win them any privilege. Not only do Sammy’s fuck-words refer to little or nothing; by force of repetition they nullify the ostensible reference of the words they accompany. Here is a passage where Sammy, at home between his periods in jail, is lying in his bath listening to soul music on the radio:

Fucking shite man propaganda. Whereas country music was for adults. Some of it anyway. That’s how ye hardly got it on the radio, they dont fucking like ye listening to it, the powers-that-be, know what I’m saying, adult music, they dont like ye listening to it. Mind you but this programme Sammy was tuned into, the cunt that did his DJ had a bad habit of talking ower the intros I mean they dont fucking do that for the classical stuff, the cunts wouldnay dream of talking ower the opening bits, the first movement, these fucking MPs man they would ask questions in parliament if they started that kind of carry on, the House of Lords and aw that, there would be a fucking revolution man these MPs and their constituents.

While most of How Late it Was, How Late is a soliloquy, there are many passages, including the one just quoted, in “free indirect style,” as linguists call it: third-person narration in which the words used are not those an omniscient narrator would speak but those Sammy would speak if he were in charge of telling the entire story. There is no disinterested observer. As a result, Sammy’s subjectivity is protected from the irony of a different point of view or another structure of values. In the film of Scarface, Tony Montana (Al Pacino) talks bad language more unstoppably than anyone I have ever heard, on screen or off, but his wife is allowed to say, at one point: “Can’t you open your mouth just once without saying fuck?” Tony answers, succinctly: “Fuck off.” In How Late it Was, How Late Sammy’s language goes unquestioned except for a moment in which Ally, an excon ambulance-chaser, advises him to tone down the expletives for tactical reasons in dealing with the authorities:

Look eh pardon me; just one thing, ye’re gony have to watch yer language; sorry; but every second word’s fuck. If ye listen to me ye’ll see I try to keep an eye on the auld words.

Sammy declines:

Dont fucking tell us how I shouldnay be, or how I should be, dont fucking tell us that.

We are left with, in effect, one character, Sammy, a name, a voice, and his subjection to a few lethal events. Other characters exist mainly to send his soliloquies deeper into rage. The only words Sammy refuses to say are those with which he would pity himself. But this scruple is enough to make How Late it Was, How Late a tour de force, a tour of Sammy’s force and of Kelman’s.

Patrick McCabe’s reputation largely depends upon The Butcher Boy (1992), a gothic tale of small-town Ireland in which a boy, Francie Brady, starts out sounding like Tom Sawyer and ends up murdering a local woman, Mrs. Nugent. Francie’s mother is insane and drowns herself; his father is a drunk. Francie gets a job in a pig slaughter-house. The culture The Butcher Boy intuits—though realism is not the whole story—is a mixture of Catholicism and TV, with the addition, for Francie, of comics and the Beano Annual. Here is a passage from the scene in which Francie kills Mrs. Nugent with a “humane killer,” the gun with which his boss kills pigs:

Hello Mrs Nugent I said is Mr Nugent in I have a message for him from Mr Leddy. She went all white and stood there just stuttering I’m sorry she said my husband isn’t here he’s gone to work oh I said that’s all right and with one quick shove I pushed her inside she fell back against something. I twisted the key in the lock behind me. She had a white mask of a face on her and her mouth a small o now you know what it’s like for dumb people who have holes in their stomachs Mrs Nugent. They try to cry out and they can’t they don’t know how. She stumbled trying to get to the phone or the door and when I smelt the scones and seen Philip’s picture I started to shake and kicked her I don’t know how many times. She groaned and said please I didn’t care if she groaned or said please or what she said. I caught her round the neck and I said: You did two bad things Mrs Nugent. You made me turn my back on my ma and you took Joe away from me. Why did you do that Mrs Nugent? She didn’t answer I didn’t want to hear any answer I smacked her against the wall a few times there was a smear of blood at the corner of her mouth and her hand was reaching out trying to touch me when I cocked the captive bolt. I lifted her off the floor with one hand and shot the bolt right into her head thlok was the sound it made, like a goldfish dropping into a bowl. If you ask anyone how you kill a pig they will tell you cut its throat across but you don’t you do it longways. Then she just lay there with her chin sticking up and I opened her then I stuck my hand in her stomach and wrote PIGS all over the walls of the upstairs room.

Here the grotesque play of tones, the decorum of middle-class conversation, gestures learned from films and TV—“and with one quick shove”—the bizarre detail of smelling the scones and seeing Philip’s picture, the formal note on the art of killing a pig: these keep readers moving insecurely from one sense of the scene to another. We are not allowed to settle upon a final understanding of Francie: the next phrase is likely to upset the judgment we have made.

There are no such scenes in The Dead School, a story of two teachers separated by a generation. One of them, Raphael Bell, was born in Charleville, County Cork, in 1913, and grew up happily till his father was killed by a Black-and-Tan, a British mercenary. A scholarship boy, Raphael goes on to become a teacher and enjoy living in Dublin in the 1930s. We read of the Eucharistic Congress in 1932 and of the great tenor John MacCormack singing César Franck’s “Panis Angelicus” on that occasion. In 1937 Raphael becomes principal of St. Antony’s School. A generation later Malachy Dudgeon, born into a miserable family in (I think) County Long-ford, grows up dire and unforgiving. He too goes to St. Patrick’s Training College in Dublin and prepares to become a teacher. “It was 1974 in Dublin and was it good to be alive,” the anonymous narrator says on Malachy’s behalf:

Outside the buses groaned like they were on their way to the wrecking yard. Beneath Daniel O’Connell’s statue a skinhead kicked the air mercilessly with his Doc Martens as a bunch of Skin Girls urged him on, clapping and singing. Outside The Ambassador the hippies queued up for Pink Floyd at Pompeii. A tramp looked in the window and played a few bars of a song for them on a busted harmonica then went off laughing and giggling to himself

McCabe’s book asks us to believe that Malachy destroys Raphael’s life and then, more gradually, his own. I am willing to suspend my disbelief, but sluggishly. I assume that McCabe had in mind a social novel, broad in scale, contrasting the Ireland of John MacCormack with the Ireland of Pink Floyd, Horslips, skinheads, secularization, and the IRA. But the contrast, page by page, is laborious; it seems less an act of the novelist’s imagination than an effort of the amateur sociologist; it does not issue with any conviction from the scenes as given. Much of the writing is casual, like “mercilessly” in the passage just quoted—how does mercy arise in the skinhead’s kicking the air? The novelist’s imagination is not engaged.

Dublin has always been a more diverse city than McCabe’s novel implies. Yeats wrote of “the daily spite of this unmannerly town,” but it had its good manners, too. The Dublin of Joyce’s Ulysses is not the same as Yeat’s Dublin or even the same as Sean O’Casey’s. In the past twenty years Dublin has become even more various: everything depends on the scene you choose and the point of view you adopt. Roddy Doyle’s streets are not Maeve Binchy’s. So it is vain of Patrick McCabe to cite a few social commonplaces of twenty years ago and hope they will bring a city to convincing life. He is trying to make social allusions do his work for him. Later chapters in The Dead School, when Malachy is living rough in London, strike me as more credible, but that may be because I don’t know the scene as well as I know Dublin. The Dead School is not at all as powerful as The Butcher Boy, but then few novels are.

Bernard MacLaverty was born in Belfast and now lives in Glasgow. He is best known for two novels, Lamb and Cal. In each of these he found his fated theme: the conflict between one’s desire and one’s given social role. In Belfast he saw Catholic and Protestant, Loyalist and Nationalist, at odds, in enmity. In Glasgow I imagine even a soccer match would keep his theme alive: Glasgow Rangers versus Glasgow Celtic, an inveterate conflict. In the title story of Walking the Dog two Loyalist gunmen looking for a Catholic seize a man who turns out to be some sort of Protestant or no-religion-at-all. His name is John Shields, not a Catholic name if my recollection of years in the North is accurate. The gunmen order him to recite the alphabet, because in Catholic schools the boys call the eighth letter “haitch” and in Protestant schools the custom is “aitch.” In the end, the gunmen let him go, but it’s a close call.

In “A Silent Retreat” a Catholic boy, Declan, gets into conversation with a B-Special, a part-time policeman, outside the Maze Prison near Belfast: not a thing I would ever have done, incidentally, even though there were B-Specials in my father’s barracks in Warrenpoint. Taunting the boy and pointing a gun at him, the B-Special says:

I’m giving the orders. Say your prayers. Yes—yes what a good idea. Say after me—Our father WHICH art in heaven…

Catholics in Ireland say WHO, not WHICH. Declan backs away from the B-Special, and hears him shouting, “Education nowadays isn’t worth a tup-ney fuck.”

Not surprisingly, the most enjoyable story in the book is set in Spain. Jimmy and Maureen—Catholics from Northern Ireland, twenty-five years married, he’s a teacher, she hasn’t a job—are on vacation: it could be Torremolinos, Marbella, anywhere. Inevitably they bring along their northern curiosity and their demotic English, middle-class version. When Jimmy pesters Maureen to tell him about her early sexual experiences, she refuses: “What is this—where did all this shite suddenly come from, Jimmy?” When she tries to persuade him to stop questioning her about sex, he says, “Fuck off.” But the story soon develops in more interesting ways. Maureen wanders off by herself and for an hour or two lives a deeper life than her married one. The story is among MacLaverty’s best.

A few general comments suggest themselves, however tentatively. In 1931 W.B. Yeats wrote:

The romantic movement with its turbulent heroism, its self-assertion, is over, superseded by a new naturalism that leaves man helpless before the contents of his own mind.5

Yeats thought that Joyce, as a case in point, could merely express whatever happened to be in his mind at the time; and that Joyce’s limitation in that respect was typical of the age. The only way of avoiding this predicament, Yeats thought, was to fill your mind with images from gone times and better times—the Japanese Noh, Renaissance art, Greek sculpture—and set your mind to prescribe the relations between its enhanced contents. If these fictions by Kelman, McCabe, and MacLaverty are at all representative, we may be in a further phase of naturalism, with this difference: that these writers are presenting characters the contents of whose minds are for the most part degraded. There is hardly anything else in them but the images and gestures of mass urban culture. The minds have no control over their contents; these characters are condemned merely to express themselves at any moment. They are what their time has made them. Perhaps this is what proletarian art has come to, though there is no reason to believe that the higher classes are exempt from such subjection. In Some Versions of Pastoral (1935) William Empson defined proletarian art “in a narrow sense” as “the propaganda of a factory-working class which feels its interests opposed to the factory owners’.”6

Of the novels and stories under review, Kelman’s are clearly the most proletarian in that sense. The police beat Sammy blind. He is helped by ordinary folk, his own kind, to cross the streets. He is a hero because he is too decent to claim sympathy for himself: he pretends that he fell, had an accident, and that his blindness may be temporary. He doesn’t object to being governed by his betters, only to letting them enjoy without comment the felicity of rank and power. Sammy’s betters are at no real risk from him, he is too honorable to let his anger spill over into action. He rails against his masters, but only in talk, and mostly to himself. Kelman’s novels and stories are fictions of disillusion and resentment. They speak of a working class and a lower-middle class sick with disappointment. In Kelman’s mind this may coincide with the collapse of the British miners’ strike under Edward Heath’s government, the move to the right by the administrations of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, and the alleged collusion of the Labour Party with the Tories.

McCabe’s novels, too, are proletarian in Empson’s sense. He even implies that Francie had the right instincts but should have kept them under better control. In The Dead School Malachy shouldn’t have acted against Raphael, but at least he was willing to be sacked for his misdeeds. MacLaverty’s fiction has more to do with caste and religion than with conflicts of class. When Jimmy and Maureen in Spain see three men drinking near the beach and hear them talk in a Northern Ireland accent, they start wondering: Are they priests, or maybe policemen? These are categories, roles rather than classes.

Whatever the reasons, the characters in these fictions by Kelman, McCabe, and—less so—MacLaverty are extraordinarily constrained in every respect but their speech, and their speech is merely the degraded dialect of their tribe. Even the murder of Mrs. Nugent is, in a sense, a correlative to the debased contents of Francie’s mind. None of these characters has any social feeling, or takes pleasure in belonging to a class or a society. In A Disaffection Pat Doyle thinks he is in love with Alison Houston, but he hasn’t the faintest notion of her as a person, separate in her identity and to be valued for that distinction. She has no aura for him. In The Dead School the characters shuffle from one episode to the next, but none of them feels the radiance of having a purpose in life. How Late it Was, How Late ends with poor Sammy on his way to the Glasgow Central Station where he may or may not take a train to Birmingham. It doesn’t matter: Glasgow or Birmingham. Going south to England doesn’t make any difference, there are no new metaphors there. The critic F.W. Bateson once said that Romanticism was the shortest way out of Manchester. Or maybe out of Birmingham. The same thing.

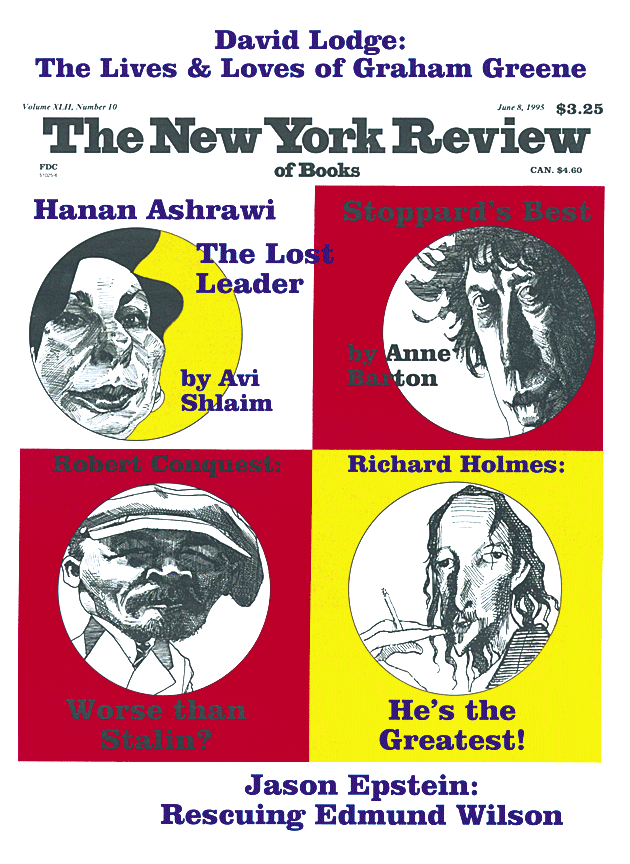

This Issue

June 8, 1995

-

1

Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy (Essential Books, 1957), pp. 23–24. ↩

-

2

Tom Leonard, On the Mass Bombing of Iraq and Kuwait, Commonly Known as “The Gulf War” (Stirling, Scotland: AK Press, 1991), p.8. ↩

-

3

See Gordon Craig’s account of Glasgow writers: ” ‘Glesca Belongs to Me!’ ” The New York Review, April 25, 1991, p. 12 ↩

-

4

Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy, p. 77. ↩

-

5

W.B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (Macmillan, 1961), p. 405. ↩

-

6

William Empson, Some Versions of Pastoral, revised edition (New Directions, 1974), p.6. ↩