1.

Harry Clément Ulrich Kessler, known in the Weimar Republic as the “Red Count,” was a rich German patron of the arts whose family lived in Paris and sent him at twelve from a bleak French school to St. George’s, a fashionable English prep school (where he missed Winston Churchill by a term), and then to a Gymnasium in Hamburg where he spent some of the most wretched years of his early life. He was a strikingly beautiful boy.

Like Schopenhauer, who had received a similar education in three countries, he refused to go into business with his well-to-do father. He became an art lover, a cosmopolitan wanderer among cultures. In the seemingly stable world of solid bourgeois prosperity before the First World War, he was for years oblivious of current politics. After the war, during the Weimar Republic, he was a leading pacifist and anti-Nazi; after Hitler’s rise to power, a political refugee in France. A passionate collector, Kessler spent several months each year in Paris and London visiting galleries and the studios of his friends. In a well-known portrait of 1906 by Edvard Munch, now in the Munch Museum in Oslo, Kessler contemplates the world with the air of an experienced connoisseur: a good-looking young man wearing a canary yellow wide-brimmed hat, painted full-length against a mauve and orange background. He seems to be leaning backward, as E.M. Forster said about Cavafy, “at a slight angle to the universe.” Many commented on his appearance. “Sometimes he appeared German, sometimes English, sometimes French, so European was his character,” his friend Annette Kolb, a fellow exile in Paris, wrote after his death.

His real home was in the arts and the world of ideas. In this he resembled other outsiders, secular German Jewish, or partly Jewish, artists and intellectuals, to whom he was attracted throughout his life; among them were his friends Albert Einstein, the poet Hugo von Hoffmannsthal (with whom he jointly wrote the scenario for Der Rosenkavalier), Rudolf Hilferding, and Walther Rathenau, respectively finance and foreign minister during the Weimar Republic. He was especially close to Rathenau, who may have been the only man in the social and political elite of Berlin to openly oppose war in 1914, and who broke into tears when he heard the news of Germany’s declaration of war. In 1922, Rathenau was assassinated by a proto-Nazi for favoring reconciliation with Germany’s former enemies and for being a “Judenschwein.”

Kessler wrote a deeply felt biography of his late friend, with whom he strongly identified for both personal and political reasons. Both were outsiders, loners; both could not shake off the influence of overpowering fathers; both were frustrated artists. Kessler was homosexual, and it is likely that Rathenau was as well. Kessler’s book was more than a biography.1 Like most Germans in 1914, he had been enthusiastic about the war (a marvelous “purifying fire”), and he put a lot of his own experience into the book, which can be read as an essay in self-criticism.

Laird M. Easton, a history professor at California State University, has written a thoughtful, well-researched, and fascinating biography of Kessler’s life that is also a contribution to the history of fin de siècle avant-garde art. Kessler’s antecedents were mixed. His father, Adolf, was a Paris banker who, on his mother’s side, descended from an old Hamburg banking family and on his father’s side from a long line of German and Swiss pastors; the family spent only the summer months in Germany, often at a fashionable spa. Adolf Kessler was a committed republican, resentful of the prejudices and social circumstances in imperial Germany. Under his apparent influence, in 1896, Harry decried Wilhelm II’s cheap posturing, his “beastliness,” “brutality,” and his “clownish hairlock,” as though he were already speaking of Hitler.2

Kessler’s mother, Alice Harriet Blossé-Lynch, was born in Bombay. Her mother was said to be a close relative of the shah of Iran; her Anglo-Irish father was well known as a high British naval officer and the founder of a navigation company on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Kessler worshiped his mother. She was, he wrote, “one of the queenly race of Englishwomen with their mixture of matter of factness, soaring passion and imagination and the irrationality of certain Shakespearean heroines.” Her beauty captivated, among many others, the aging German emperor Wilhelm I, who, after meeting her on the promenade at Ems, bestowed the title “von” on Adolf Kessler and his heirs and then induced the head of a minor German principality, Heinrich XIV of Reuss, to raise Adolf Kessler to the rank of count, giving rise to rumors that plagued Harry throughout his life that he was the emperor’s illegitimate son.

When the Kesslers lived in France, “tout Paris” came to Alice’s salon—Sarah Bernhardt, Eleanora Duse, Maupassant, Ibsen, Zola, the young Rodin, as well as assorted duchesses, Rothschilds, Italian aristocrats, visiting rich Americans, and politicians. The spectacle of “society,” Easton writes, fascinated Kessler from his youth in much the same way as it did Proust. He was at home in “high society” wherever he went. In Berlin he was on the edge of the tightly exclusive “court society.” His curiosity was insatiable. He had a passion for bringing creative people together, arranging for Hugo von Hoffmannsthal and Aristide Maillol to meet in Athens and go on together to Delphi. He hoped that Max Reinhardt, Proust, Nijinsky, and Richard Strauss would somehow produce together a Gesamtkunstwerk.

Advertisement

In his diary he recalled what he saw and heard as if he were quite conscious that no one else of his time had his range of acquaintance and insight into different worlds. In London he dined with George Bernard Shaw, Herbert Asquith, and Edward Grey, in Paris with Raymond Poincaré, Proust, Cocteau, and Bernard Berenson, who wondered why Kessler did not write his books in French: “I answered, ‘Because I am a German.'” He became close as well to struggling avant-garde artists whom he supported financially, and to other penniless bohemians, poets, dancers, male and female models, wrestlers, cabaret performers, trapeze artists, boxers, cyclists, and other athletes. In Berlin, during the brief “Golden Twenties,” he rarely went to bed before 2 or 3 AM.

Early on, as James Fenton wrote in these pages a few years ago, Kessler “identified the one disappointing defect” in the art of his close friend Aristide Maillol, “his utter lack of interest in the male nude,” and took it upon himself to remedy it.3 He took Maillol to boxing matches in the East End of London, offered to hire some of the boxers as models, and commissioned Maillol to do a statue of his own current lover, a young man named Gaston Colin, a cyclist who raced in the Tour de France. The statue stood for years in Kessler’s study, while Maillol’s magnificent statue of a crouching young woman, La Méditerranée, was in his library. Kessler toured the French countryside with Colin and recommended him to his sister Wilma—“splendid young fellow, extremely courageous, adroit in all sports and manly“—as a fitting companion to her son. The affair with Colin lasted until at least the First World War, when the two men found themselves in opposing armies.

Kessler had a splendid apartment in Berlin and a house on the Cranachstrasse in Weimar. Both were designed by the Belgian art nouveau architect Henry van de Velde, whom he helped make considerably popular at the time. The house in Weimar was close to Nietzsche’s sister’s house, where he once stayed overnight and remembered hearing the sick Nietzsche moaning and screaming “into the dark with all his might.” Kessler’s two houses were variously described as “temples of art.” The walls were hung with paintings by Seurat, Re-noir, and Cézanne. The Cranachstrasse house was described by his close friend Helene von Nostitz, Field Marshal Hindenburg’s niece and the only woman Kessler may have wanted to marry:

The fire burned in the hearth and threw its light upon the festive rider of the Parthenon frieze. Light yellow books stood in white bookcases. In the glass vitrines… lovely, small figures of women by Maillol stared in the mirror which reflected their pure, restrained forms. Over a matted violet divan the nymphs of Maurice Denis ran through a fantastic forest. Before the window stood an ancient bronze Chinese vessel.

His father died in 1895, leaving Harry and his sister a sizable fortune. He moved about Europe restlessly, usually in grand luxury, accompanied by a valet (who later turned out to have been a Nazi spy). Traveling to Brussels in 1921 with Einstein to attend a pacifist congress, he observed that Einstein had apparently never been in a first-class wagon-lit compartment before and examined its amenities “with the greatest of interest.” In the cosmopolitan European social world before the great war, Kessler had a more than passing acquaintance with Thomas Mann, D’Annunzio, Rilke, Serge Diaghilev, Proust, Max Reinhardt, Cocteau, Richard Strauss, Isadora Duncan, and George Bernard Shaw. After the war he was also in touch with Kokoschka, Brecht, Harold Nicolson, Hermann Hesse, Aristide Briand, Gustav Stresemann, André Gide, and Georg Grosz. As the Nazis rose to power, Grosz called Kessler the last great gentleman he had encountered.

Kessler was forty-six when World War I broke out; he volunteered immediately and served as a captain in an elite Prussian guards regiment. He saw action first in neutral Belgium, which the Germans devastated in a few days, shooting hostages and burning down villages. On his way there, he traveled comfortably in a private first-class compartment; his horse, his valet, and the lower ranks under his command stretched out on hay in cattle cars. In Namur, a town the Germans had partially leveled, he was under orders to take prisoner the Duchess of Sutherland, at whose house in London he had dined only a few weeks earlier and discussed modern art. He felt, he noted, “somewhat uncomfortable.”

Advertisement

He expected German troops to march into Paris within weeks but already knew that he would not be among them. His army corps had just received orders to proceed to the Eastern Front and push the Russian army out of East Prussia. He spent the next sixteen months in the plains and swamps of Poland and Carpathian Russia, where he kept himself regularly supplied with French and English newspapers, English turtle soup in violet tin buckets, pâté de foie gras, and other delicacies sent to him through neutral Switzerland by English friends and his French brother-in-law. In October 1915, still enthusiastic about the war, Kessler wrote that he could accept peace only if it included large German territo-rial gains in Europe and a German-controlled land bridge all the way down to South Africa. Early in 1916, he was sent back to the West to a command post outside Verdun, a landscape of mass slaughter where hundreds of thousands of men died in the mud and clouds of gas hovered over the battlefield.

In Verdun he had a nervous breakdown. It was not only the physical strain, the brutal waste of human lives; as Easton writes, at Verdun he was fighting against the soldiers of one of his three “homelands.” It must have occurred to him that Gaston Colin, to whom he was still sending money from time to time, may have been “serving in the trenches opposite.”

After his nervous breakdown, he was sent to Switzerland, ostensibly as a cultural attaché at the German embassy, but really as a secret agent charged by the moderates in the German foreign ministry to sound out his French contacts on the possibility of peace without annexations. His direct superior, the German ambassador in Bern, was an old schoolmate who shared Kessler’s growing reservations about the war. In Switzerland, and during frequent visits to Berlin, Kessler’s political ideas changed. He met with pacifists like George Grosz and writers like René Schickele and Lion Feuchtwanger (the first German writer to succeed in smuggling a pacifist poem past a careless censor); he supported radical students evading military service and other draft dodgers and even deserters and drug addicts. Kessler helped where he could to protect them from the German war machine. He admired their youthful idealism. Easton quotes the French pacifist Romain Rolland, who wrote: “Count Kessler in Bern, who is responsible for German cultural propaganda, is a person of very fine taste and generous character, who takes German artists and intellectuals under his wings even when they are revolutionarily inclined.”

Among the latter were Grosz, Hellmuth Herzfelde (later Heartfield), and the philosopher Ernst Bloch, the apostle of socialist utopianism and future author of The Principle of Hope. He was, Kessler noted in his diary, “an almost shockingly powerful Jew, with a bull neck, wild evil dark eyes behind a pince-nez and an untamed shock of hair; a brutal force of nature who—not without vanity—has set himself the task of rethinking the world.” Bloch reminded him of the Jewish boxers in the East End of London whom he had introduced to Maillol, men “superior to the strongest English rowdies.”

In October 1918, German sailors mutinied in Kiel. Kessler rejoiced at the news of the Kaiser’s flight and abdication. Revolution quickly spread throughout the country. In less than six days after the mutiny in Kiel there were uprisings in Bremen, Cuxhaven, Leipzig, Munich, and Berlin. “The opposite of France,” Kessler observed, “the province revolutionizes the capital, the sea—the land.” It was a peaceful revolution at first, with hardly a shot fired. That it would be a failed revolution—largely because of the reluctance of the victorious Social Democrats to reform the old power structures—became evident only later. Kessler was deeply frustrated over this failure. The German revolution, the German historian Sebastian Haffner wrote after the war, was the only social democratic revolution squashed by a social democratic government.

Kessler’s friend Rathenau was equally frustrated: “There was no revolution,” he wrote. “The doors only sprung open. The wardens ran away. The captives stood dazzled in the prison courtyard, incapable of moving their limbs.” The two men talked to each other of their mutual despair. The German revolution of 1918—the word itself soon seemed a misnomer—fused old myths of German superiority with deadly new ones that Hitler did not have to invent. By the summer of 1919, they were already in place. Karl Kraus had them in mind in The Last Days of Mankind when he wrote of the Germans generally: “They will have forgotten that they lost the war, forgotten that they started it, forgotten that they waged it. For this reason it will not end.”

2.

After the war, Kessler became more restless than ever. His friends could not immediately make sense of the changes in him. Back in Berlin in December 1918, he visited the imperial palace soon after it had been ransacked by mutinous German sailors. In the empress’s private rooms, he walked through the hideous clutter of tasteless objets, past smashed doors and furniture and walls hung with trite paintings in the grand patriotic style; he saw vast armoires stuffed with kitschy plates, trinkets, souvenirs, medals, and other knickknacks. He felt no anger at the looters, only “astonishment” at the mediocrity of the people who had collected this trash. “Out of this atmosphere was born the World War, or whatever guilt for the World War was the Kaiser’s,” he notes. “I feel no pity, only aversion and a sense of my own complicity when I reflect that this world was not destroyed long ago, but on the contrary still continues to exist, in somewhat different forms, everywhere.”

Kessler’s biography of Rathenau, published in 1928, is still the best that has appeared, although several others were published after World War II. “He put himself into the book on nearly every page,” Easton says, “without, however, diminishing his subject.” It is, as Easton writes, Kessler’s “single most important political testament.” Kessler also wrote essays on art and on his travels, as well as a memoir of his youth. He was a bibliophile and publisher of greatly admired fine editions of works by Virgil and Shakespeare. Illustrated by Maillol, they were printed on beautiful wood-free India paper produced in a workshop he established at Marly outside Paris and in a typeface specially designed for him by Eric Gill and Gordon Craig in England. In the early days of the Weimar Republic he dabbled in national politics, mostly unsuccessfully: together with Rathenau, Max Weber, Einstein, Theodor Wolff (editor of the Berliner Tageblatt), and other prominent liberals, he was one of the founders of the strongly republican German Democratic Party (DDP). In the elections to the Constituent Assembly of the Weimar Republic, their party was the second strongest but in subsequent elections it became weaker until, on the eve of Hitler’s rise to power, it virtually disappeared.

He also dabbled briefly and unsuccessfully in diplomacy, in the interest of German reconciliation with its former enemies. He lectured tirelessly in support of the German peace movement and the league of Nations, proposing to strengthen the league by expanding its membership to include not only the official representatives of nation-states but also, in a voting capacity, trade unions, chambers of commerce, economic organizations, and other civic groups. Yet for all his energy and inventiveness he might well be forgotten today were it not for the descriptive, almost cinematic, power and eloquence of the diary he kept for many years.4 It is perhaps the most important German diary of the twentieth century, comparable in its quality only to Victor Klemperer’s diary of life under the Nazis.

The parts written during the revolution of 1918 and during the stormy days of the Weimar Republic on the eve of Hitler’s rise to power are especially memorable. He rushes about Berlin from place to place like a police reporter but with the detachment of a well-informed foreign correspondent. He observes the street fighting that takes place after the Socialist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were murdered by rebellious army officers. He is in the Weimar theater where the Constituent Assembly discusses the new republican constitution (“Danton or Bismarck would seem monstrous apparitions in these dainty surroundings”), and in the gallery of the Reichstag after Rathenau’s assassination. Wagner’s funeral march for Siegfried echoes through the chamber; in the box once used by the Kaiser, the dead man’s mother, pale as wax, stares at the coffin. “Many of those around me wept.” A few days later, Kessler visits his friend Maximilian Harden, a veteran political commentator who has just barely escaped an assassin. Harden has long maintained that Germany had brought its disaster on itself. For this, two hired thugs attack him in the street with iron bars. “Can I live in this country any longer?” Harden asks Kessler.

Kessler had a painterly eye for faces, urban landscapes, and works of art, a knack for the telling detail, and an almost photographic memory for conversations. When Einstein comes to dinner and admires Maillol’s La Méditerranée in the library, his informality and humor—rare among the overly self-important Germanic Professorat —fascinate Kessler. “The ironical (narquois) trait in Einstein’s expression, the Pierrot Lunaire quality, the smiling, pain-ridden skepticism that plays about his eyes becomes ever more noticeable.”

On another occasion he notes the contrast between the Einsteins and their prominent dinner guests, mostly rich Berlin Jews. “This really loveable, almost still childlike couple lent an air of naiveté to a typical Berlin dinner party,” saving it “from being conventional and transfiguring it with an almost patriarchal fairy-tale quality.” After the other guests have gone, the Einsteins and Kessler remain in the living room chatting. The conversation touches Einstein’s relativity theory. Kessler confesses that he “feels” rather than truly “understands” its importance. In a half-page of text, one of the most memorable in the diary, Kessler quotes Einstein almost word for word as he explains his theory in a manner that is at once simple, convincing, and profound. Einstein says he can’t see why people make so much fuss over it: “When Copernicus dethroned the earth from its position as the center of creation, the excitement was understandable.” But his own theory has not really changed humanity’s view of itself.

One evening after a dinner party in his Berlin apartment, Josephine Baker takes her clothes off and dances for Kessler and his guests around Maillol’s La Méditerranée. “She…became preoccupied with it, stared at it, copied the pose, rested against it in bizarre postures…. Maillol’s creation was obviously much more interesting and real to her than we humans standing about her.” In Auden’s words, Kessler was a “crown witness to his time.”

Except for Rathenau and Gustav Stresemann, Kessler was critical of Germany’s new republican leaders. He assumed that two thirds of the population rejected the new republic or supported it only halfheartedly. As the number of political assassinations (mostly carried out by the extreme right) rose, he said that human life in Germany had become as cheap as in a Central American banana republic. The judiciary was by and large sympathetic toward right-wing thugs. Though Kessler seems to have never read Mein Kampf, Easton shows that he warned against the possibility of Hitler overthrowing the government a year before the Beer Hall Putsch of 1922. Kessler distrusted and feared the Communists and despised the Social Democratic leaders for their lack of character and principle. Like Einstein, he had little confidence in them and in the stability of the republic. He believed that the unholy alliance—to combat communism—between the Social Democrats and the “Free Corps” of disgruntled officers of the defeated army undermined all prospects of bureaucratic reform. He had nothing but contempt for leading Weimar politicians such as Philip Scheidemann, the first republican chancellor, “inflated like a peacock in his concertina trousers,” or Matthias Erzberger, leader of the Center Party (soon to be assassinated for signing the armistice agreement), or Hugo Preuss, “father” of the Weimar constitution. They were inept, provincial bores.

The so-called “moderate” right wing frightened Kessler. He tried vainly to warn Stresemann, the foreign minister, against the election of the senile field marshal Paul von Hindenburg as president of the republic. Upon Hindenburg’s election in 1925 Kessler writes:

All the philistines are delighted…. He is the god of all those who long for a return to philistinism and the glorious time when it was only necessary to make money and digest with an upward glance…. Farewell to progress, farewell to a new vision of the world which was to be humanity’s ransom money for the criminal war.

(Hindenburg would eventually appoint Hitler chancellor.)

Everywhere Kessler went on his lecture tours he found that the middle class was rejecting both democracy and peace. “The misery of the German middle class was in large part due to the intensive servility of the many German courts…. Germans owe it to their princes that they are the most educated but also the most spineless people in Europe.”

In a strongly argued coda to his excellent biography Easton maintains that conventional measures cannot be applied to Kessler’s life. He was a gifted amateur with no firm vocation and no fixed place in life. The apparent contrast between the snobbish, slightly effete, seemingly disengaged fin de siècle aesthete of the pre-war years and the committed democrat and pacifist after 1918 is misleading: the moral energy and intelligence that produced the postwar man of action were present long before. In his willingness to challenge convention and his ability to transcend it, there was an inner logic to his evolution.

He ended in exile, sad and lonely. Kessler had already lost parts of his fortune during the war; his holdings in England were seized and sequestered as war reparations. Much of what was left was used up by his extravagant style of life and almost completely wiped out during the crash of 1929. He had to close his publishing house and start selling his art collection. His Maillols and Rodins and his paintings by Cézanne, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Seurat went first; his rare books last. Some of his valuable possessions were looted by servants or seized by the Nazis on trumped-up charges of tax evasion. During his last years in exile, a sick and lonely man, he lived modestly in a borrowed house in Mallorca and in a simple pension in Burgundy, supported by his sister. He died in 1937 and was buried in Paris in the cemetery of Père Lachaise.

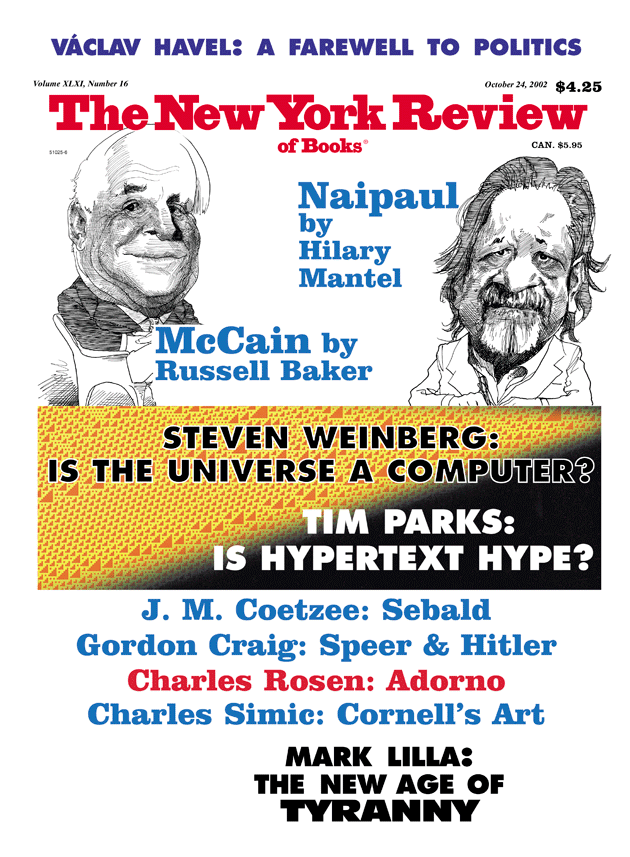

This Issue

October 24, 2002

-

1

Walter Rathenau: His Life and Work (AMS Press, 1970). ↩

-

2

Peter Grupp, Kessler’s German biographer, cited in Claudia Schmölders, Hitlers Gesicht (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2000), p. 27. ↩

-

3

“The Secrets of Maillol,” The New York Review, May 9, 1996. ↩

-

4

Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918–1937), translated and edited by Charles Kessler, with an introduction by Ian Buruma (Grove, 1999). The full diary is said to consist of 15,000 densely written pages. It is now being prepared for publication on CD-ROM. ↩