There always have been and always will be artists who possess a remarkable or uncanny talent and a huge accompanying ambition—and the gift isn’t large enough to sustain the ambition. Max Beckmann, for example, was a powerful painter with a mordant sense of his own era, but among the last places a viewer should look for evidence of his best qualities are the large triptychs by which Beckmann set so much store and yet which are, like so many of his other later, symbol-laden, myth-suffused pictures, unrelievedly portentous. But probably there are few artists where the split between gift and ambition is so striking as it is with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

In a career which ran through nearly the first two thirds of the nineteenth century, Ingres made portraits which, whether in the form of oil paintings or pencil drawings, are among the most extraordinary in the history of art. Then there are the works that, done over the same years, he seems to have thought were his more meaningful achievements. These were the so-called history pictures, whether showing moments in the life of Christ, French kings, or literary and mythological beings, such as Zeus, Paolo and Francesca, and Oedipus. They are pictures which, as made clear by his recent retrospective at the Louvre, an even larger gathering of his work than the 1967 exhibition marking the centennial of his death, may be intriguing in a biographical or theoretical way but are, as works of art, bland, impersonal, or unrefreshingly odd. Depending on what section you were in, the Louvre’s show was exhilarating one moment and flat and lifeless the next. The exhibition presented a towering figure, but a man whose genius was felt only when, leaving himself to one side, he put his energy into recreating the person before him. On his own, free to invent, he was rather a nobody.

Ingres’s story is seemingly inseparable from a tumultuous moment in European history, out of which he emerged as both hero and victim. He was the foremost pupil of Jacques-Louis David, the painter whose images, taken from the Greek and Roman past or from contemporary life, and done over the period from the 1780s to the early nineteenth century, embodied aspects and even goals of the French Revolution and the early years of the Napoleonic era that followed it. Born in 1780 and therefore a young man during the heady days of Napoleon’s reforms at home and conquests abroad, Ingres came into his own (to put it in the broadest terms) during a more confident, even swaggering, time, if not a more truly settled or secure one. His art, accordingly, has crucial similarities to that of his teacher, except that where David painted with an underlying moral sense, an awareness of a continuing social, political, and ethical crisis—seen most spectacularly, perhaps, in The Death of Marat, done not long after the event, in 1793—his student worked with a deeply sensual, and certainly apolitical and amoral, feeling for the material here and now. It was a changeover that the younger man seems not to have understood fully, or wanted to understand.

Ingres was like a son who has all the talent and drive necessary to take over his father’s business, and, charged by his father’s accomplishment, becomes possessed by sheer dutifulness. Yet, because of his own more secure upbringing, and because the more genuinely chaotic era his father lived through is over, he gets only the shell, or form, of what his predecessor did. At the same time, he has mixed feelings about his own unique power—his ability to seize and reconstitute the sentient being before his eyes. Not that Ingres thought of his portraits as hackwork. He brought the same perfectionist intensity to everything he did. He gave himself as fully, in addition, to the sitters he faced in his early years, when he was based largely in Italy and his subjects were frequently friends or chance acquaintances, as he did when, back in France from his middle years on, his subjects were often persons of great wealth and social or political prominence.

It isn’t easy to say how or why Ingres’s portraits are so momentous. In his approach, he wasn’t greatly different from the way Holbein, say, worked in the early 1500s or from the way Bronzino or other Italian portraitists worked some years later. There are in Ingres’s portraits the same miraculous superfine realism untouched by much sense of brittleness or fussiness and the same firm clarity to all the shapes and forms. As with Holbein (or with the earlier Jan van Eyck, with whom Ingres was compared by his first viewers), we are given paintings with beckoning enamel-like surfaces that we feel we look through, to encounter perfectly realized clothes, flesh, upholstered furniture, and a wide range of jewelry, items that, much to our delight, turn out on closer inspection to be no more than passages of sparklingly clear, dense, and glidingly smooth-to-the-touch oil paint.

Advertisement

Ingres, who copied the work of Holbein and that of other earlier artists (a number of his copies were on view at the show), would have proudly agreed that little in his art was new. Always in a sense a son, but having moved on from David, he was certain, by his early forties, that painting had reached its peak with Raphael, and that the best that succeeding artists could do was match the High Renaissance painter (the assumption being that they never could). Ingres’s guiding principle, about which he became only more adamant as he aged—and which was more intimidating than challenging to other artists (and also meant that his followers were likely to be sheep)—was that traditional, time-honored, academically sanctioned values, with a special emphasis put on the importance of line, or form, over color, were the only route to the beautiful.

What Ingres did was to make his sitters more physically tangible and psychologically present than they had been in most earlier portraits, whether by Renaissance artists or David. By the same token, the figures in his pencil portraits, created out of controlled maelstroms of ethereally soft shading, vigorous darting marks, and powerfully assured and sinuous, repeating lines, seem more forthrightly present than the sitters not only in earlier drawings but in the drawings of any era. And where the sitters in earlier portraits by one or another artist tend to be a touch uniform in their presence, Ingres, working with the visual facts presented by the person before him, plus whatever he might have known about the person—in many cases, especially with the drawings, he would not have known a great deal—created one rounded, fully autonomous character after another. Encountering good numbers of these paintings and drawings in the Louvre’s show (or in “Portraits by Ingres,” the staggeringly rich exhibition seen at the National Gallery, London, the Metropolitan Museum, and the National Gallery, Washington, in 1999 and 2000*) was like walking through, as it were, the work of a novelist who is less concerned with a protagonist than an array of characters who, in a flowing, organic way, sum up an entire era.

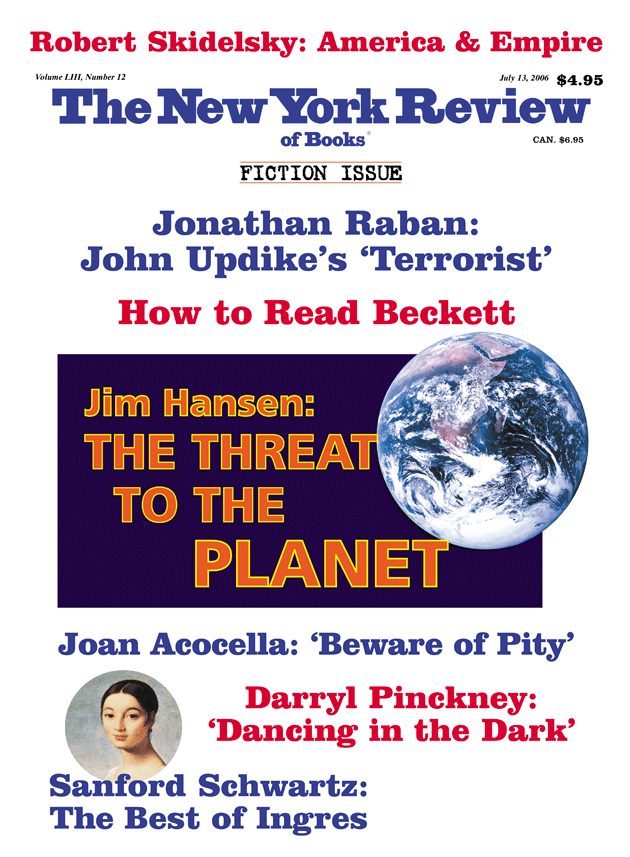

It is no surprise to learn that Norvins, for example, with his nervous eyes and tight little lips, was at the time the chief of police in Rome, where the picture was made. Granet is the essence of a soulful and dashing artist and appears to have heard this already. Mme Leblanc, who seems to smile with her eyes, is ready to hear, and accept, anything we want to divulge. Mlle Rivière, with her wide, dark eyes and white boa draped over her arms, has proven over time to be a near-peerless image of young womanly grace (see the detail on the cover). Molé, who conveys a rumpled sweetness and playful irony, and might pass as a high school history teacher, turns out to have been a widely admired politician. Mme Moitessier, clearly someone with clout around the house, looks in one portrait to be done in by the pressure of keeping up appearances, while in a second portrait an enigmatic omniscience asserts itself. The sitters in Ingres’s pencil drawings, which are often no more than a foot high, are, as individuals, every bit as substantial to our eyes.

Looking at Ingres’s portraits is such a filling experience it comes as a surprise to realize how pared down his approach was. While in his portrait drawings he might present on the same sheet a couple or siblings, parents and children or children on their own, people and their pets or with their musical instruments, even figures standing at specific locations in a city, his painted portraits generally show only one person, and then almost never in full figure. And while in a handful of the painted portraits he includes a cityscape or landscape behind the sitter, in most he presents the fewest items, none of which, thankfully, come across as keys to who the person is. Yet Ingres is so precise and considered about every square inch of his given portrait that subsidiary elements, which might be no more than the wallpaper behind the sitter, or the jewelry being worn, or the position of his or her body within the picture as a whole, or the particular colors involved, become, as we think back on the work, companions to that person.

In the portrait of Molé, which is set in a darkened and nearly empty room, we are held by bits of light falling on two separate zones of furniture. In the portrait of Baronne James de Rothschild (see illustration on page 6), what catches us, besides the Baronne’s alluring face and amazing gray and red dress, is the relationship between the good amount of plain wall behind her and the precise way she and her dress make up the lower part of the picture, a relationship that suggests a graceful descent down a chutelike space. Mme de Senonnes, in her portrait, also seems to be sliding down and out of the picture, although with more slithery abandon. Behind her is one of Ingres’s mystery-inducing mirrors, showing us, as Ingres paints her reflection, Mme de Senonnes’s inert self. But what most stamps the painting is the ketchup-and-mustard play of her red dress against the golden yellow tones of the sofa she sits on and of the wall behind her. The portrait of Mme Marcotte, whose glassy eyes perhaps indicate allergies, highlights even more unusual colors in the way the sitter’s coppery brown dress comes up against the yellow sofa she is on, a rare conjunction, sour yet autumnal, reminiscent of Josef Albers.

Advertisement

Portraiture, however, was, Ingres professed, a chore. To satisfy a colossal ambition, he couldn’t be a portraitist anyway, but had to work on what his age considered the loftiest ground. The resulting historical, mythological, and religious pictures bespeak huge amounts of energy and industry, but, conveying little palpable sense of inner tension, are costume dramas. The faces we encounter are those of real people who have been carefully observed but have little of the life seen so regularly in the portraits. The faces in the history pictures are essentially those of models waiting for the session to be over. When an emotion is to be expressed, it comes across stridently, or woodenly. The extraordinarily precise and dramatic feeling for color that Ingres shows in his portraits also forsakes him here. Rich hues are so abundantly present that they cancel each other out.

The very subjects of the history pictures, taken as a whole, have a deadening variousness. In paintings such as Jupiter and Thetis, from 1811, or Oedipus and the Sphinx, an image he tackled in 1808 and again in 1864, Ingres’s terrain was the classical and mythical past, while in the huge 1827 Apotheosis of Homer, which shows the poet receiving adulation on Mount Olympus, the illustrious artists and writers of all time are also present. Religious themes were handled in, to take some examples, Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter, from 1820, The Virgin with the Host, from 1854, and, eight years later, Jesus Among the Doctors. The European past provided the settings for small pictures done a little before 1820 about the lives of Renaissance painters and kings—The Death of Leonardo da Vinci and Henry IV Playing with His Children are examples—and also for such monumentally sized works as Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII, from 1851–1854, and The Vow of Louis XIII, dated 1824.

For Ingres and his time, paintings that were essentially celebrations of women’s bodies seem to have qualified as history pictures, too. Roger and Angelica, a mythical tale with roots in Christian and classical sources which Ingres did in one version after another over many years, presents a nude woman, chained to a rock and threatened by a dragon, who is about to be saved by a knight riding his half-horse, half-bird hippogriff. In other works, the female form is seen in less rattled moments. Giving the subject a semblance of the exotic and removed in time, Ingres showed, in the 1808 Bather of Valpinçon, say, or the 1814 Grande Odalisque (or in pictures dated right into the last years of his career), luxuriantly resting nude women in settings suggestive of palaces of Middle Eastern potentates.

Random and chaotic as all this is, and considering that some of the subjects came to Ingres as government or church commissions, there is a certain unity to these works. There is even, at least on paper, a connection between them and his portraits. Whether he presents, on the one hand, Jesus, Homer, or harem life, or, on the other, Granet, Molé, or Mme de Senonnes, Ingres’s chosen mood, or theme, was order, power, and glory. Although his occasional portrait subject can seem distracted or under the weather, his sitters generally exude a kind of bodily and philosophical robustness and readiness. In the confident way they wear their magnificent clothes, they personify, at the very least, sheer abundance or amplitude. And while the history scenes occasionally revolve around moments of strife or crisis, Ingres was clearly happier—or his image, anyway, seems less purely manufactured—when he could delineate attainment in itself, a moment when the struggle for power (if struggle there was) is over, and the basking in the light, as it were, can begin.

Ingres was himself a power-mad monster with, depending on one’s point of view, the added vice, or the saving grace, of self-doubt. The pattern of his life had much to do with his famous thin skin, the other side of his famous quest for glory. The son of an artist, Ingres arrived in Paris in 1797 and, soon a leading student of David’s, won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1801 for his painting The Ambassadors of Agamemnon. Eventually set up at the French Academy in Rome a few years later, he found his first submissions to the Paris Salon, in 1806, poorly received, largely because his intensely realistic art, with its clear edges for forms, was new and discomforting for viewers at the time. Their response led not only to Ingres’s indignation but to a breaking up of his engagement with his fiancée in France—in good part because his spirits were crushed and he refused to return to Paris. After his years at the Academy’s Villa Medici were over, he stayed on in Rome, making pencil portrait drawings of visitors to the city to support himself and the woman he eventually did marry, Madeleine Chapelle, whom he had brought from France, sight unseen, as a sort of mail-order bride. From Rome he continued to send paintings to the Salon and to be incensed at the less than loving reception they received.

By 1824 Ingres was finally back in Paris, where his work was positively reviewed for the first time in the Salon of that year. The official honors he sought began to descend. After a decade of smooth sailing, however, the response at the Salon to The Martyrdom of Saint Symphorian, a historical machine on which he had labored for years (and which is not in the Louvre’s show), was met with some coolness, even derision, prompting the painter to declare that he would never show at the Salon again. Once more finding the atmosphere of Paris untenable, he immediately applied for the newly available position of director of the French Academy in Rome, which he received and where he worked with characteristic diligence until 1841, the year he deemed propitious for a return to Paris (his second). The current monarch, Louis-Philippe, was a huge admirer, as would be succeeding figures of power in France for the rest of Ingres’s lifetime. And while Madeleine’s death, in 1849, after thirty-six years of marriage, left him bereft—their only child had died at birth—he formed a second strong marriage in 1852, with Delphine Ramel, twenty-eight years his junior.

By the late 1860s, the last decade in his life, Ingres had amassed more honors, including an appointment as senator, than any French painter ever. But one feels that the same stormy temperament remained to plague him and those who crossed his path. It was his insecurity that kept him so blinkered, even dictatorial, in his tastes, believing that any kind of art other than his own version of Raphael’s unruffled and academically correct manner was worthless. His craving for fame, accompanied by an inability to resist flattery, and his fearfulness, accompanied by a propensity for sulking, had for years made the short—and eventually portly—painter an irresistible target for the press. How offputting his egoism could prove can be judged by the way he is treated in Andrew Carrington Shelton’s new Ingres and His Critics, a highly detailed yet somewhat confusing study that describes how Ingres, determined to control every aspect of how his work was seen, helped pull down the Salon system for showing new art and was instrumental in bringing about its replacement, the one-person exhibition.

The changes Shelton describes seem inevitable and healthy, and they would have happened regardless of the touchy M. Ingres. But Shelton, who contributed solidly informative essays to the catalogs for the “Portraitsby Ingres” and the Louvre’s shows, may have spent too much time with his subject over the years. In his book, he seems to find Ingres reprehensible at every turn. His pictures are treated with a clinical distance, and more than once his behavior is called “childlike.” On the other hand, the combination in Ingres of a grandiose ambition and a canary’s sensitivities may help explain his well-known attentiveness to his students’ needs and his highly effective and practical-minded stint as director of the Villa Medici. The artist’s self-absorption, anyway, didn’t preclude his being able to give himself wholeheartedly to his sitters or to sustain long friendships. It didn’t get in the way of his sometimes presenting his portrait drawings to the sitters as gifts. And surely Ingres’s dread of looking vulnerable played a part in his striving, most successfully in the painted and drawn portraits, to bring his realistic detailing to the precisely right degree of definition, or focus, over every aspect of the canvas or sheet.

Not all of Ingres’s work, of course, falls neatly into the categories of brilliantly achieved portraiture or moribund costume epic. There is a fascinating gray zone of pictures that straddle categories and give an idea of where the artist might have gone if he hadn’t boxed himself in with his all-or-nothing ambition. An amazing portrait of Queen Caroline of Naples, which turned up only in 1987, shows what might have happened if the artist had mixed into his painted portraits the properties of his drawings, where we often see sitters in full, in specific places. Every aspect of the painted full-length portrait of Caroline (who was one of Napoleon’s sisters) has a tingling aliveness and strangeness, whether the glowingly blue lamp above her head, the forcefully elongated, black-clad shape of Caroline herself, the intensely clear details of the room, or the sparkling view out the window to the Bay of Naples and the distant city beyond, done entirely in the form of little white dots.

The Ingres who one wishes had more frequently trained his sharp eye on the everyday life of his time can also be seen in The Sistine Chapel, a documentary-like painting from 1820 of Pope Pius VII at a service there. Faithfully recording the scene as he saw it, the artist captures not only the particular dulled-down light of the room but the way a ceremonial rug has been sloppily left askew, a homely detail that gives us the odd sense of being able to walk right into the image. As many commentators and, no doubt, viewers, see it, however, the truly alluring gray zone of Ingres’s work less concerns his piercing naturalism than his obsession with line in itself and with the female nude. It isn’t rare to read that the female nudes, in their “hallucinatory” way (as a wall label at the Louvre put it), are as substantial as the portraits. The Bather of Valpinçon, where the nude is seen from the back, wearing only a red and white cloth turban, and Grande Odalisque, where the figure reclines with her back to us and turns to give us a look, are owned by the Louvre and have become over the years almost emblems of Ingres’s art. A detail of The Bather forms the cover of the Louvre’s exhibition catalog, and the same picture in other publications has been treated as an emblem of the museum itself.

For their admirers, the first of whom appears to have been Baudelaire (as Shelton notes), the nudes are about the fluidly rounded outline of a woman’s body, or shape in itself. Far from being merely imaginative recreations of harem life, the argument runs, the pictures are contemplations of form, and, as such, precursors of nudes by Picasso and Matisse. More than that, it is in the odalisques, and to a lesser extent in some of his earlier history pictures and later portraits, where Ingres, perhaps driven by fantasies about the female form, occasionally takes liberties with anatomy and line, giving his figures unnaturally pliant, elongated, or overly fleshy fingers, necks, arms, or breasts. Considering his martial belief in correct anatomy, it might be said that when he makes this or that person’s neck look like a swan’s neck, or essentially forgets that people have bones, Ingres is letting himself go. We might be seeing a kind of safety valve at work, the way the artist, possibly not even fully aware of it himself, escaped from his insistent need for bodily exactitude.

The oddities have certainly been much noted. According to Shelton, the painter’s “sole salvation with regard to modernist art history has always been the formal quirks and visual disjunctions that characterize his work.” Seeing so much of his art in the Louvre’s exhibition led this observer, however, to believe that Ingres’s “quirks” and “disjunctions” add up, in the end, to very little. It is true that much of the charm of his small Paolo and Francesca, say, derives from Paolo’s cartoonishly stretched-out body, as he goes to kiss Francesca. But there is no larger, meaningful pattern to these absurdities. There are few of them, all told, in any event. And when, in his portraits, Ingres makes a woman’s arm or her fingers rubbery, the detail is not in itself what gives the picture its power. The exaggerations don’t even amount to a mannerism.

Further, one can believe that the female nudes, despite the amount of amazingly painted flesh on display, are somewhat dormant as artworks. An exception is an 1819 oil study for the woman in Roger and Angelica, where the entirely nude studio model takes her pose not in an actual space but against colors that enhance her skin. The bold simplifications of the study, especially when seen alongside the various finished versions of the inane Roger and Angelica, made the painting one of the delights of the show. Yet the work’s formal liveliness is an inadvertent byproduct of Ingres’s approach. We appreciate it the way we do certain pieces of folk art, because they remind us of something else.

What makes Ingres urgent and exciting is not when he creates a sex object touched with anatomical peculiarities but when he bumps up against, and feels he must master, someone with a distinct character. If his few male nudes, which were done at the onset of his career, have a greater erotic charge than his many female concubines, it may be because these images of studio models aren’t, like the harem scenes, about the contemplation of a piece of property but suggest an atmosphere of rivalry, heroism, and accomplishment. As shown in pictures by his teacher David, by the slightly younger Théodore Géricault, and by other artists who were roughly his contemporaries, Ingres worked in an age that was nothing if not a call for the enterprising and physically prepossessing young man to take center stage—an age with an enchanted idea of youthful male endeavor and fellowship.

Ingres’s pictures and his successful marriages strongly suggest that his own, personal concern in the matter wasn’t sexual. But the spirit of male virility, which David showed to be a crucial element equally in pictures of the Greek and Roman past and of the present, certainly carried Ingres along in the portraits he made in his early days in Rome, when he was around thirty years old. In these images of the dreamboat Granet, the bluff Moltedo, and the sensitive Cordier, where the subjects are placed against stormy skies and bits of the Roman scene, and they all wear wonderfully painted large white collars, Ingres, it seems, has taken the spirit of male mastery so common in artworks in the Napoleonic era and brought it down to earth. He has taken an era’s quest and given it complex human faces. And while he made breathtakingly beautiful portraits for decades after these Roman works, it is possible to believe that nothing he did thereafter has quite the same combination of sweetness, bright intensity, and passionate warmth.

This Issue

July 13, 2006

-

*

Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch,catalog of the exhibition edited by Gary Tinterow and Philip Conisbee (Abrams/Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999). ↩