###1.

Earlier this year, I visited the famous basilica of Saint-Denis, on the outskirts of Paris. I admired the magnificent tombs and funerary monuments of the kings and queens of France, including that of Charles Martel (“the hammer”), whose victory over the invading Muslim armies near Poitiers in 732 AD is traditionally held to have halted the Islamization of Europe.1 Stepping out of the basilica, I walked a hundred yards across the Place Victor Hugo to the main commercial street, which was thronged with local shoppers of Arab and African origin, including many women wearing the hijab. I caught myself thinking: So the Muslims have won the Battle of Poitiers after all! Won it not by force of arms, but by peaceful immigration and fertility.

Just down the road from the basilica of the kings, in the discreet backyard offices of the Tawhid association, I met Abdelaziz Eljaouhari, the son of Berber Moroccan immigrants and an eloquent Muslim political activist. He talked with fluent passion, in perfect French, about the misery of the impoverished housing projects around Paris—which, as we spoke, were again wracked by protests—and the chronic social discrimination against immigrants and their descendants. France’s so-called “Republican model,” he said furiously, means in practice “I speak French, am called Jean-Daniel, and have blue eyes and blond hair.” If you are called Abdelaziz, have a darker skin, and are Muslim to boot, the French Republic does not practice what it preaches. “What égalité is there for us?” he asked. “What liberté? What fraternité?” And then he delivered his personal message to Nicolas Sarkozy, the hard-line interior minister and leading right-wing candidate to succeed Jacques Chirac as French president, in words that I will never forget. “Moi,” said Abdelaziz Eljaouhari, in a ringing voice, “Moi, je suis la France!”

And, he might have added, l’Europe. For the profound alienation of many Muslims—especially the second and third generations of immigrant families, young men and women themselves born in Europe—is one of the most vexing problems facing the continent today. If things continue to go as badly as they are at the moment, this alienation, and the way it both feeds and is fed by the resentments of mainly white, Christian or post-Christian Europeans, could tear apart the civic fabric of Europe’s most established democracies. It has already catalyzed the rise of populist anti-immigrant parties, and contributed very directly to the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001 (hijackers such as Mohamed Atta were radicalized during their time in Europe), the Madrid bombings of March 11, 2004, the murder of the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh on November 2, 2004, the London bombings of July 7, 2005, and the planned attempt to blow up several passenger planes flying from Britain to the US, foiled by the British authorities on August 10, 2006.

Europe’s difficulties with its Muslims are also the subject of hysterical oversimplification, especially in the United States, where stereotypes of a spineless, anti-American, anti-Semitic “Eurabia,” increasingly in thrall to Arab/Islamic domination, seem to be gaining strength.2 As an inhabitant of Eurabia, I must insist on a few elementary distinctions. For a start, are we talking about Islam, Muslims, Islamists, Arabs, immigrants, darker-skinned people, or terrorists? These are seven different things.

Where I live—in Oxford, Eurabia—I come into contact with British Muslims almost every day. Their family origins lie in Pakistan, India, or Bangladesh. They are more peaceful, law-abiding, and industrious British citizens than many a true-born native Englishman of my acquaintance. As the authors of an excellent new study of Islam in France point out, most French Muslims are relatively well integrated into French society.3 Much of the discrimination Abdelaziz Eljaouhari complains about, which exists in different forms and degrees in most European countries, applies equally to non-Muslims of immigrant origin. It is, so to speak, indiscriminate discrimination against people with darker skins and foreign names or accents; plain, old-fashioned racism or xenophobia, rather than the more specific prejudice that is now tagged Islamophobia.

Across the continent of Europe, there are a number of very different, albeit overlapping, issues concerning Islam. The Russian Federation has more than 14 million people—at least 10 percent of its rapidly shrinking population—who may plausibly be identified as Muslim, but most Europeans don’t consider them as part of Europe’s problem.4 In the case of Turkey, by contrast, a country of nearly 70 million Muslims living in a secular state, Europeans hotly debate whether such a large, mainly Muslim country, which has not been considered part of Europe in most traditional cultural, historical, and geographical definitions, should become a member of the European Union. In the Balkans, there are centuries-old communities of European Muslims, more than seven million in all, including one largely Muslim country, Albania, another entity, Kosovo, which will sooner or later be a state with a Muslim majority, and Bosnia, a fragile state with a Muslim plurality, as well as significant minorities in Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro.

Advertisement

These Balkan Muslims are old Europeans and not immigrants to Europe. However, like the Turks, they do form part of the Muslim immigrant minorities in west European countries such as Germany, France, and Holland. Within a decade, most Balkan Muslims will probably be citizens of the European Union, either because their own states have joined the EU or because they have acquired citizenship in another EU member state. The shameful feebleness of western Europe’s response to Serbian and, to a lesser degree, Croatian persecution of Bosnian Muslims in the 1990s has fed into a broader sense of Muslim victimhood in Europe. That west Europeans (and the US) intervened militarily in Kosovo to prevent an attempted genocide of Muslim Albanians by Christian Serbs is less often remembered.

When people talk loosely about “Europe’s Muslim problem,” what they are usually thinking of is the more than 15 million Muslims from families of immigrant origin who now live in the west, north, and south European member states of the EU, as well as in Switzerland and Norway. (The numbers in the new central and east European EU member states, such as Poland, are tiny.) Although counting is complicated by the fact that the French Republic, being in theory blind to color, religion, and ethnic origins, does not keep realistic statistics, there are probably somewhere around five million Muslims in France—upward of 8 percent of the total population. There are perhaps four million—mainly Turks—in Germany, and nearly 1 million, more than 5 percent of the total population, in Holland.

Most of them live in cities, and generally in particular areas of cities, such as the administrative region around Saint-Denis, which contains some of the most notorious housing projects on the outskirts of Paris. An estimated one out of every four residents of Marseilles is Muslim. In his fascinating new book, Murder in Amsterdam, Ian Buruma cites an official statistic that in 1999 some 45 percent of the population of Amsterdam was of foreign origin, a figure projected to rise to 52 percent by 2015, with the majority of those people being Muslim. And Muslim immigrants generally have higher birth rates than the “native” European population. According to one estimate, more than 15 percent of the French population between sixteen and twenty-five years old is Muslim.5

So with further immigration, high relative birth rates, and the prospect of EU enlargement to the Balkans and perhaps Turkey, more and more citizens of the EU are going to be Muslim. In some urban neighborhoods of Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Holland they will make up anywhere between 20 and 90 percent of the population. Most of them will be young; far too many will be poor, ill-educated, underemployed, alienated—feeling at home neither in the place they live nor in the lands from which their parents came—and tempted by drugs, crime, or political and religious extremism.

If we, the—for want of a better word—traditional Europeans, manage to reverse the current trend, and enable people like Abdelaziz and his children to feel at home as new Muslim Europeans, they could be a source of cultural enrichment and economic dynamism, helping to compensate for the downward drag of Europe’s rapidly aging population. If we fail, we shall face many more explosions.

2.

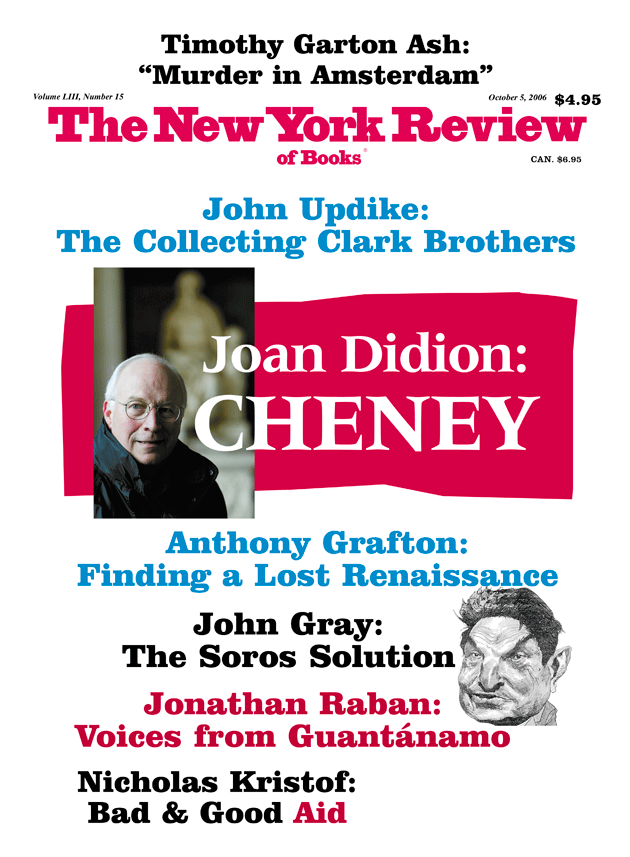

Ian Buruma—half-Dutch, half-British, and wholly cosmopolitan—has had the excellent idea of returning to his native Holland to explore the causes and implications of the murder on November 2, 2004, of Theo van Gogh, a filmmaker and provocative critic of Muslim culture, by a twenty-six-year-old Moroccan Dutchman named Mohammed Bouyeri. Arriving on a bicycle, Bouyeri shot van Gogh several times on a public street, then pulled out a machete and cut his throat—“as though slashing a tire,” according to one witness. He used another knife to pin to van Gogh’s chest a long, rambling note, calling for a holy war against all unbelievers and the deaths of a number of people he abhorred, starting with the Somali-born Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali, to whom the note was addressed. Van Gogh and Ms. Ali had together made the short film Submission, which dramatizes the oppression of women in some Muslim families by projecting quotations from the Koran onto the half-naked bodies of young women, as they intone personal stories of abuse. Bouyeri’s murder note concluded:

I know for sure that you, Oh America, will go down

I know for sure that you, Oh Europe, will go down

I know for sure that you, Oh Netherlands, will go down

I know for sure that you, Oh Hirsi Ali, will go down

I know for sure that you, Oh unbelieving fundamentalist, will go down

One question that preoccupies Buruma in Murder in Amsterdam, a characteristically vivid and astute combination of essay and reportage, is: Whatever happened to the tolerant, civilized country that I remember from my childhood? (He left Holland in 1975, at the age of twenty-three.) What’s become of the land of Spinoza and Johan Huizinga, who claimed in an essay of 1934 that if the Dutch ever became extremist, theirs would be a moderate extremism? Van Gogh’s murder was, Buruma writes, “the end of a sweet dream of tolerance and light in the most progressive little enclave of Europe.” Yet part of his answer seems to be that the reality always differed from the myth of Dutch tolerance—if one looks, for example, at wartime and postwar attitudes toward the Jews. And he quotes a remarkable statement by Frits Bolkestein, a leading Dutch politician and former European commissioner: “One must never underestimate the degree of hatred that Dutch people feel for Moroccan and Turkish immigrants.” Not “Muslims,” note, but immigrants from particular places.

Advertisement

Now Buruma revisits the verdant suburbs of his childhood (the words “verdant” and “leafy” recur), talking to intellectuals and those he ironically calls Friends of Theo, hearing their accounts of how the Dutch model of multiculturalism, with separate “pillars” for each culture, broke down. Too many immigrants were allowed in too fast, and they were not sufficiently integrated into Dutch society, linguistically, culturally, or socially. The parents were brought to Holland to work as what the Germans call Gastarbeiter, guest workers, but their children are mainly left unemployed.

As for Dutch attitudes toward Islam, Buruma suggests that people like the anti-immigrant populist politician Pim Fortuyn were so angry with the Muslim reintroduction of religion into public discourse because they had just “painfully wrested themselves free from the strictures of their own religions,” meaning Catholic or Protestant Christianity. Not to mention Muslim attitudes toward homosexuals—Fortuyn was gay—and women. Questioned about his hostility to Islam, Fortuyn said “I have no desire to have to go through the emancipation of women and homosexuals all over again.” Like van Gogh, Fortuyn was also murdered, Dutch-style, by a man arriving on a bicycle, though his assassin was not a Muslim. Van Gogh was fascinated by Fortuyn; in fact, Buruma writes, the filmmaker was making a “Hitchcockian thriller” about Fortuyn’s assassination when he was himself killed by Bouyeri.

The responses of people like Fortuyn and van Gogh are the more accessible part of this story for us non-Muslim Europeans, or more generally Westerners. What we really need to understand is the other part: the experience of the Muslim immigrants and their descendants. Was the killer Mohammed Bouyeri a lone madman or the symptom of a larger malaise? The answer is not reassuring. Bouyeri comes from what I call the Inbetween People: those who feel at home neither in the European countries where they live nor in the countries from which their parents came. They inhabit “dish cities,” connected to the lands of their parents’ birth by satellite dishes bringing in Moroccan or Turkish television channels, by the Internet, and by mobile phones. Unlike most Muslim immigrants to the US, many of them physically go “home” every summer, to Morocco, Algeria, Turkey, or other countries in Europe’s near abroad, sometimes for months at a time. In their European homes, the second generation often speaks the local language—Dutch, French, English—with their brothers or sisters and the native language—Berber, Arabic, Turkish—with their parents: “50–50,” as one Berber-Moroccan Dutchman tells Buruma. Buruma asks which soccer team this man would support. Morocco! Which passport would he rather have? Dutch!

Almost all the young people I met in the riot-prone housing projects around Paris told similar stories of a life between: of idyllic summers spent at their grandparents’ farms in Algeria and Tunisia; of divided loyalties, crystallized by the question “Which soccer team do you support?” “Algeria!” those of Algerian descent told me—and a 2001 match between Algeria and France famously degenerated into a nasty riot. But when the Algerian-French Zinedine Zidane led the French team in the World Cup, they supported France.6 “In Morocco I’m an émigré, in France, I’m an immigré,” said Abdelaziz Eljaouhari.

Culturally, they are split personalities. And the disorientation is not just cultural. Buruma meets a psychiatrist specializing in the mental problems of immigrants. Apparently women, and the first generation of immigrant men, tend to suffer from depression; second-generation men, from schizophrenia. According to his research, a second-generation Moroccan male is ten times more likely to be schizophrenic than a native Dutchman from a similar economic background.

Mohammed Bouyeri was one of those second-generation Berber-Moroccan Dutchmen, torn this way and that. He attended a Dutch high school named after the painter Piet Mondrian, spoke Dutch, drank alcohol, smoked dope, had an affair with a half-Dutch, half-Tunisian girl. He was attracted to Western girls, but furious when his sister found a boyfriend, Abdu. Sex before marriage was fine for himself, but not for her. The traditionally all-important family honor was thought to be irreparably stained in the eyes of his Moroccan Muslim community by a daughter or sister having sex before marriage. Bouyeri attacked Abdu with a knife and went to jail for a spell. His mother died of breast cancer. Mohammed turned his back on what he now increasingly saw as decadent European ways. He grew a beard, took to wearing a Moroccan djellaba and prayer hat, and came under the influence of a radical Takfiri preacher from Syria. He posted Islamist tracts on the Web and watched videos of foreign infidels in the Middle East having their throats cut by holy warriors. According to a Dutch source cited by Buruma, Bouyeri’s friend Nouredine passed his wedding night with his bride on a mattress in the future assassin’s apartment, watching infidels being slaughtered.

On November 1, 2004, Mohammed Bouyeri spent a quiet evening with friends. They went out for a stroll, listening to Koranic prayers through headphones attached to digital music players. Mohammed remarked how beautiful the night sky looked. Next morning he rose at 5:30 AM, prayed to Allah, and then bicycled off to butcher van Gogh. He apparently intended to get killed himself in the ensuing gunfight with police.

Bouyeri’s story has striking similarities with those of some of the London and Madrid bombers, and members of the Hamburg cell of al-Qaeda who were central to the September 11, 2001, attacks on New York. There’s the same initial embrace and then angry rejection of modern European secular culture, whether in its Dutch, German, Spanish, or British variant, with its common temptations of sexual license, drugs, drink, and racy entertainment; the pain of being torn between two home countries, neither of which is fully home; the influence of a radical imam, and of Islamist material from the Internet, audiotapes, or videocassettes and DVDs; a sense of global Muslim victimhood, exacerbated by horror stories from Bosnia, Chechnya, Palestine, Afghanistan, and Iraq; the groupthink of a small circle of friends, stiffening one’s resolve; and the tranquil confidence with which many of these young men seem to have approached martyrdom. Such suicide killers are obviously not representative of the great majority of Muslims living peacefully in Europe; but they are, without question, extreme and exceptional symptoms of a much broader alienation of the children of Muslim immigrants to Europe. Their sickness of mind and heart reveals, in an extreme form, the pathology of the Inbetween People.

3.

Buruma devotes a chapter to Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Submission, the film she made with Theo van Gogh showing the mistreatment of Muslim women. Ali’s own story has been told in countless profiles and interviews. In fact, she is irresistible copy for journalists, being a tall, strikingly beautiful, exotic, brave, outspoken woman with a remarkable life story, now living under permanent threat of being slaughtered like van Gogh. Among the many awards listed on the back cover of her new book of essays, The Caged Virgin, next to the Moral Courage Award, the International Network of Liberal Women Freedom Prize, Dutchman [sic] of the Year 2004, the Coq d’Honneur 2004, and the Danish Freedom Prize, is Glamour magazine’s Hero of the Month Award. That’s how we like our heroes—glamorous. It’s no disrespect to Ms. Ali to suggest that if she had been short, squat, and squinting, her story and views might not be so closely attended to.

While both books under review were at the press, a further scandal erupted around her. The hard-line Dutch immigration minister, Rita Verdonk, revoked Ms. Ali’s Dutch citizenship, after a Dutch television report had “revealed” that she had given false details when applying for asylum in the Netherlands in 1992. (In fact, Ali had already told the story herself many times; when Buruma suggested to her that she was, in a phrase often used by the British tabloid press, a bogus asylum-seeker, she replied, “Yes, a very bogus asylum-seeker.”) The minister’s harsh decision provoked a storm of protest in the Dutch parliament, where Ayaan Hirsi Ali was a representative of Verdonk’s own party. Verdonk was compelled to revoke her revocation, and the coalition forming the Dutch government fell apart as a result. But the damage had been done. Ali announced her resignation from the Dutch parliament and her intention to move to the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

Having read many interviews with her, and spent an evening in London talking to her both onstage and off, I have enormous respect for her courage, her sincerity, and her clarity. This does not mean one must agree with all her views. The Caged Virgin is subtitled, in its American edition, “An Emancipation Proclamation for Women and Islam.” It would be more accurate to call it a manifesto for the emancipation of women from Islam. She tells horrifying, true stories of the oppression and abuse of young women in some Muslim immigrant families in Europe, based on her experience first as an interpreter and then as a politician. Some of these young women are forced to marry people they don’t want to marry—she uses the term “arranged rape.” Others are abused by husbands, fathers, or uncles. If they try to leave, or take up with a boyfriend, they are intimidated, beaten, and even murdered in “honor killings.” Ali writes that there were eleven such killings of Muslim girls in just two police districts of Holland in the space of seven months in 2004 and 2005.

Young girls from countries like Somalia are submitted to what is euphemistically called “female circumcision”—a procedure she describes as involving “the cutting away of the girl’s clitoris, the outer and inner labia, as well as the scraping of the walls of her vagina with a sharp object—a fragment of glass, a razor blade, or a potato knife, and then the binding together of her legs, so that the walls of the vagina can grow together.” Ali rightly describes this not as “female circumcision” but as “genital mutilation.” (She herself was subjected to this horrifying procedure, at the behest of her Somali grandmother.) And she writes a moving and very practical text entitled “Ten Tips for Muslim Women Who Want to Leave”—preparing them for the shock, pain, and possible danger of leaving a Muslim family.

Ali performs a great service in drawing our attention to these horrors, which are the dark underside of a supposedly tolerant “multiculturalism.” However, some Muslim women object to the way in which she blames their oppression on the religion of Islam, rather than on the specific national, regional, and tribal cultures from which they come. (Ali herself acknowledges that genital mutilation is not prescribed in the Koran.) Buruma reports a televised meeting she had with women in a Dutch shelter for abused housewives and battered daughters, several of whom objected strongly to the film Submission. “You’re just insulting us,” one cried. “My faith is what strengthened me.” According to Buruma, she dismissed their objections with a lofty wave of her hand.

Submission was always meant to be a provocation. Muslim culture, Ali writes, needs something like Monty Python’s The Life of Brian, directed by an Arabic Theo van Gogh, with a Mohammed figure in the main lead. (This sentence was probably written before van Gogh’s murder; the Dutch edition of this book appeared in 2004.) She recalls that a decisive moment in her own experience was reading a book called The Atheist Manifesto. She also drew inspiration from John Stuart Mill’s essay “On the Subjection of Women.” “I ask that we do question the fundamental principles” of Islam, she says. And on the last page of her book she concludes that “the first victims of Mohammed are the minds of Muslims themselves. They are imprisoned in the fear of hell and so also fear the very natural pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness.”

Having in her youth been tempted by Islamist fundamentalism, under the influence of an inspiring schoolteacher, Ayaan Hirsi Ali is now a brave, outspoken, slightly simplistic Enlightenment fundamentalist. In a pattern familiar to historians of political intellectuals, she has gone from one extreme to the other, with an emotional energy perfectly summed up by Shakespeare: “As the heresies that men do leave/are hated most of those they did deceive.” This is precisely why she is a heroine to many secular European intellectuals, who are themselves Enlightenment fundamentalists. They believe that not just Islam but all religion is insulting to the intelligence and crippling to the human spirit. Most of them believe that a Europe based entirely on secular humanism would be a better Europe. Maybe they are right. (Some of my best friends are Enlightenment fundamentalists.) Maybe they are wrong. But let’s not pretend this is anything other than a frontal challenge to Islam. In his crazed diatribe, Mohammed Bouyeri was not altogether mistaken to identify as his generic European enemy the “unbelieving fundamentalist.”

Now every man and woman in Europe must self-evidently be free to advance such atheist or agnostic views, without fear of persecution, intimidation, or censorship. I regard it as a profound shame for Holland and Europe that we Europeans could not keep among us someone like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, whose intention was to fight for a better Holland and a better Europe. But I do not believe that she is showing the way forward for most Muslims in Europe, at least not for many years to come. A policy based on the expectation that millions of Muslims will so suddenly abandon the faith of their fathers and mothers is simply not realistic. If the message they hear from us is that the necessary condition for being European is to abandon their religion, then they will choose not to be European. For secular Europeans to demand that Muslims adopt their faith—secular humanism—would be almost as intolerant as the Islamist jihadist demand that we should adopt theirs. But, the Enlightenment fundamentalist will protest, our faith is based on reason! Well, they reply, ours is based on truth!

4.

The very Dutch stories of Theo van Gogh, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Mohammed Bouyeri fill only a small corner of the vast, complex tapestry of Europe and Islam. If we ask “what is to be done?” the answer is: many different things in different places. We must be foxes, not hedgehogs, to recall Isaiah Berlin’s famous use of a fragment of Archilochus: “The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Against the strident hedgehogs of Fox News we must continue to insist that this is not all just one big War on Terror, to be won by the Good Guys eliminating the Bad Guys.

Buruma rightly emphasizes the cultural diversity of Muslim immigrants: Berbers from the Rif mountains are not quite like Moroccans from the lowlands; Turks have different patterns of adaptation from Somalians, let alone Pakistanis in Britain. In the nineteenth century, European imperialists studied the ethnography of their colonies. In the twenty-first century, we need a new ethnography of our own cities. Since European countries tend to have concentrations of immigrants from their former colonies, the new ethnography can even draw on the old. At the same time, the British, French, Dutch, and German ways of integration—or nonintegration—vary enormously, with contrasting strengths and weaknesses. What works for, say, Pakistani Kashmiris in Bradford may not work for Berber Moroccans in Amsterdam, and vice versa.

We have to decide what is essential in our European way of life and what is negotiable. For example, I regard it as both morally indefensible and politically foolish for the French state to insist that grown women may not wear the hijab in any official institution—a source of additional grievance to French Muslims, as I heard repeatedly from women in the housing projects near Saint-Denis. It seems to me as objectionable that the French Republic forbids adult women to wear the hijab as it is that the Islamic Republic of Iran compels them to wear the hijab, and on the same principle: in a free and modern society, grown men and women should be able to wear what they want.7 More practically, France surely has enough difficulties in its relations with its Muslim population without creating this additional one for itself.

On the other hand, freedom of expression is essential. It is now threatened by people like Mohammed Bouyeri, whose message to people like Ayaan Hirsi Ali is “if you say that, I will kill you.” Indeed, Buruma tells us that Bouyeri explained to the court that divine law did not permit him “to live in this country or in any country where free speech is allowed.” (In which case, why not go back to Morocco?) But free speech is also threatened by the appeasement policies of frightened European governments, which attempt to introduce censorship in the name of intercommunal harmony. A worrying example was the British government’s original proposal for a law against incitement to religious hatred. This is a version of multiculturalism which goes, “You respect my taboo and I’ll respect yours.” But if you put together all the taboos of all the cultures in the world, you’re not left with much you can speak freely about.

Skilled police and intelligence work to catch would-be terrorists before they act (as the British police and security services appear to have done on August 10 this year) is essential not just to save the lives of potential victims. It’s also vital because every terrorist atrocity committed in the name of Allah hastens the downward spiral of mutual distrust between Muslim and non-Muslim Europeans. One young Moroccan-Dutch woman tells Buruma that before the September 11 attacks on New York, “I was just Nora. Then, all of a sudden, I was a Muslim.” Heading off this danger will also mean closer surveillance of the militant Islamist imams whom we repeatedly find radicalizing disaffected young European Muslim men.

From another angle, European economies need to create more jobs and make sure Muslims have a fair crack at getting them. A recent Pew poll found that the top concern among Muslims in Britain, France, Germany, and Spain was unemployment. In view of the historic sluggishness of job creation in Europe, fierce competition from low-cost skilled labor in Asia, and the reflexes of xenophobic discrimination in many European countries, this is easier said than done. Housing conditions are another major source of grievance. However, to try to remedy that through public expenditure will strain already stretched budgets; if it is seen to be done at the expense of the “native” population living nearby, it could also translate into more votes for populist anti-immigrant parties.

Europe’s problem with its Muslims of immigrant origin, the pathology of the Inbetween People, would exist even if there were an independent, flourishing Palestinian state, and if the United States, Britain, and some other European countries had not invaded Iraq. But there’s no doubt that the Palestinian issue and the Iraq war have fed into European Muslims’ sense of global victimhood. This is made amply clear by the personal stories of the Madrid and London bombers. In a recent poll for Britain’s Channel 4 television, nearly a third of young British Muslim respondents agreed with the suggestion that “the July bombings [of London] were justified because of British support for the war on terror.”8 Establishing a workable Palestinian state and withdrawing Western troops from Iraq would, at the very least, remove two additional sources of grievance. An attack on another Muslim country, such as Iran, would exacerbate it.

In the relationship with Islam as a religion, it makes sense to encourage those versions of Islam that are compatible with the fundamentals of a modern, liberal, and democratic Europe. That they can be found is the promise of Islamic reformers such as Tariq Ramadan—another controversial figure, deeply distrusted by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the French left, and the American right, but an inspiration to many young European Muslims. Ramadan insists that Islam, properly interpreted, need not conflict with a democratic Europe. Where the Eurabianists imply that “more Muslim Europeans means more terrorists,” Ramadan suggests that the more Muslim Europeans there are, the less likely they are to become terrorists. Muslim Europeans, that is, in the sense of people who believe—unlike Mohammed Bouyeri, Theo van Gogh, and, I suspect, Ayaan Hirsi Ali—that you can be both a good Muslim and a good European.9

Ultimately, this is a challenge as much for European societies as for European governments. Much of the discrimination in France, for example, is the result of decisions by individual employers, who are going against the grain of public policy and the law of the land. It’s the personal attitudes and behavior of hundreds of millions of non-Muslim Europeans, in countless small, everyday interactions, that will determine whether their Muslim fellow citizens begin to feel at home in Europe or not. Together, of course, with the personal choices of millions of individual Muslims, and the example given by their spiritual and political leaders.

Is it likely that Europeans will rise to this challenge? I fear not. Is it still possible? Yes. But it’s already five minutes to midnight—and we are drinking in the last chance saloon.

—September 6, 2006

This Issue

October 5, 2006

-

1

732 is the date generally given, but two French scholars argue that it actually occurred in 733; see J.H. Roy and J. Deviosse, La Bataille de Poitiers—Octobre 733 (Paris: Gallimard, 1966). ↩

-

2

Originally the title of an obscure journal, the term “Eurabia” seems to have been popularized by a writer called Bat Ye’or. The jacket copy of her Eurabia: The Euro-Arab Axis (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2005) summarizes its thesis: “This book is about the transformation of Europe into ‘Eurabia,’ a cultural and political appendage of the Arab/Muslim world. Eurabia is fundamentally anti-Christian, anti-Western, anti-American, and antisemitic.” Much of Ms. Ye’or’s argument, which has a strong element of conspiracy theory, is built around the alleged secret guiding influence of an organization called the Euro-Arab Dialogue (EAD). ↩

-

3

Jonathan Laurence and Justin Vaisse, Integrating Islam: Political and Religious Challenges in Contemporary France (Brookings Institution, 2006). ↩

-

4

Estimates of their number vary wildly, from as low as 3 million to as high as 30 million. In 2003, when advancing Russia’s case for being a member of the Or- ganization of the Islamic Conference, Vladimir Putin named a suspiciously round number of 20 million. See the authoritative discussion by Edward W. Walker in Eurasian Geography and Economics, Vol. 46, No. 4 (2005), pp. 247–271. I am most grateful to John Dunlop for this reference. ↩

-

5

See the very useful article by Timothy M. Savage, “Europe and Islam: Crescent Waxing, Cultures Clashing,” The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Summer 2004), pp. 25–50. ↩

-

6

Until the closing minutes of the World Cup final, I hoped that Zidane’s brilliant and disciplined performance as captain of the French team would provide an inspiring example for millions of French Muslims. Then his vicious but exquisitely executed headbutt of the white, presumably Catholic, Italian defender Marco Materazzi suggested a different kind of inspiration for European Muslims. Popular culture subsequently gave the story an unexpected twist, as a catchy and amusing song, ironically celebrating Zidane’s headbutt (coup de boule), became an instant hit in France. It can be heard at www.koreus.com/media/ zidane-coup-boule-mix.html. ↩

-

7

Note that I refer specifically to adult women. There is an argument that teenage girls might actually feel liberated by the ban on wearing the hijab in schools from what they themselves feel to be oppressive parental, communal, or religious authority. But what, then, of the rights of teenage girls who would freely choose to wear a headscarf? ↩

-

8

For this and more detail on the alienation of the younger generation of British Muslims, see my column in The Guardian, August 10, 2006. ↩

-

9

This brief summary of Ramadan’s position draws on presentations I have heard him make as a visiting fellow at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, where he will now be a research fellow for the next two academic years, attached both to the European Studies Centre and to the Middle East Centre. ↩