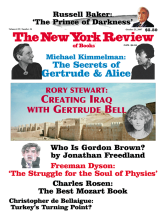

When the British needed a senior political officer in Basra during World War I, they appointed a forty-six-year-old woman who, apart from a few months as a Red Cross volunteer in France, had never been employed. She was a wealthy Oxford-educated amateur with no academic training in international affairs and no experience of government, policy, or management. Yet from 1916 to 1926, Gertrude Bell won the affection of Arab statesmen and the admiration of her superiors, founded a national museum, developed a deep knowledge of personalities and politics in the Middle East, and helped to design the constitution, select the leadership, and draw the borders of a new state. This country, created in 1920 from the three Ottoman provinces of Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul, which were conquered and occupied by the British during World War I, was given the status of a British mandate and called Iraq.

When I served as a British official in southern Iraq in 2003, I often heard Iraqis compare my female colleagues to “Gertrude Bell.” It was generally casual flattery and yet the example of Bell and her colleagues was unsettling. More than ten biographies have portrayed her as the ideal Arabist, political analyst, and administrator. Does she deserve this attention? Was she typical of her colleagues? What are the terms by which we can assess a policymaker eighty years after her death?

The British Mandate of Iraq had problems from its beginnings. A revolt in 1920 cost the British several hundred lives and an estimated £40 million and convinced them of the impossibility of direct colonial control. The monarchy, which they established under the Hashemite King Faisal—a foreigner and a Sunni with close links to the British—was unpopular with many Kurds, Shia, and nationalists. And even after Iraq joined the League of Nations in 1932, having developed some of the institutions of a modern state, it continued to be threatened by ethnic and sectarian divisions and religious and nationalist opposition. In 1958 the monarchy was brutally overthrown, in favor of military rule and then Baathist dictatorship.

Bell’s letters, now all available on-line in an archive prepared by the Newcastle University library, suggest that Bell’s strength lay not in her political success—she did not succeed in forming a sustainable, stable, unified Iraqi state—but in the clarity and imagination with which she explored failure. She wrote almost as soon as she arrived in Basra in 1916:

…We rushed into the business with our usual disregard for a comprehensive political scheme. We treated Mesop[otamia] as if it were an isolated unit, instead of which it is part of Arabia…. When people talk of our muddling through it throws me into a passion. Muddle through! why yes, so we do—wading through blood and tears that need never have been shed.

She places some blame on the pre-existing chaos, as did the Coalition Provisional Authority in 2003. In her “Review of the Civil Administration in Mesopotamia” in 1920, she notes that

if it took rather longer to open some of the Baghdad schools than expected, the delay may be attributed to the people themselves, who looted all the furniture and equipment of the schools and carried off the doors, windows and other portable fittings.

Eighty-five years later, when I was working in Amara, a city on the Tigris north of Basra, we had to replace the doors, windows, and furniture in 240 of the four hundred schools that had been looted in the province. Bell complains of the former Ottoman rulers as we did of the former Baathist leaders: the senior officials had all left, taking or destroying the most important administrative data. But she recognizes that much of this complexity and uncertainty is an inevitable element in any occupation.

By 1920, Bell had added to fluent Arabic and a decade of travels in the Middle East four uninterrupted years of experience in the British administration in Iraq. Yet she never pretends in her letters in that year to be able to predict, explain, or control events. She emphasizes the weaknesses of the previous Ottoman administration; the persistence of the tribal system; the divisions between urban and rural areas. She writes about the new state’s vulnerability to troublemakers from Syria and to new forms of nationalism and radical Islam such as the vision of a Sharia religious government, promoted by Shia clerics in their 1920 revolt.

Bell shows how RAF aerial bombardments and the cultural insensitivity of British soldiers exacerbated hatred. She portrays Iraqis who loathe foreign occupation yet worry about the alternative. She knows that the occupation is unsustainable and ineffective but she cannot contemplate total withdrawal. She recognizes that British colonial control is unworkable and that there must be an Arab government, but she finds the sacrifices and uncertainties hard to stomach. The situation, she concludes, is “strange and bewildering.”

All these themes are common paradoxes and compromises of foreign occupation, hauntingly familiar in Iraq today but rarely so crisply expressed. Instead, in 2003, we steeped ourselves in “lessons learned” and absorbed the abstract doctrines taught by Western governments for dealing with “post-conflict” situations: management, counterinsurgency, and economics. Our reports referred to “capacity-building,” “hearts and minds,” “civil society,” “truth and reconciliation,” “governance,” and “micro-credit.” Our mission statements postulated dizzying relationships between free markets and peace, terrorism and human rights, elections and growth. These opaque words obscured the gap between our aspirations and our power, concealed the necessity for compromises with lesser evils, conflated problems with solutions, and disguised our failure.

Advertisement

Bell’s writing is both more lively and more honest. She is open in her use of paradox and irony, her expression of unpleasant truths. She acknowledges impotence and comedy, without denying her moral responsibility. She admits the uncertainty and difficulty of trying to make policy in such an environment. This is almost never dressed up in jargon or platitude. To take a few examples from her letters in 1920:

…There’s no getting out of the conclusion that we have made an immense failure here. The system must have been far more at fault than anything that I or anyone else suspected. It will have to be fundamentally changed and what that may mean exactly I don’t know.

No one knows exactly what they do want, least of all themselves, except that they don’t want us.

[The politician] Saiyid Talib…is the ablest man in the country. He is also, it must be remembered, entirely unscrupulous, but his interests and ours are the same….

…We are largely suffering from circumstances over which we couldn’t have had any control. The wild drive of discontented nationalism…and of discontented Islam…might have proved too much for us however far-seeing we had been; but that doesn’t excuse us for having been blind.

[In talking to an Arab nationalist leader] I said complete independence was what we ultimately wished to give. “My lady” he answered—we were speaking Arabic—“complete independence is never given; it is always taken.”

Such comments—which may seem simple to an outsider—are difficult to articulate within an active mission and under the orders of a strong bureaucracy. Bell’s political reports avoid economic or legal or political theory and instead focus on identifying and describing the most powerful, effective, and representative Iraqi figure in specific districts, from the sheikhs on the Tigris to the ayatollahs in Najaf. Although Bell was prejudiced in favor of aristocratic tribal warriors, she was conscious that Arab notions of leadership did not correspond with her own. Thus Bell acknowledges Ibn Saud—the founder of Saudi Arabia—as the greatest leader in contemporary Arabia while conceding that

his deliberate movements, his slow sweet smile and the contemplative glance of his heavy-lidded eyes… do not accord with Western conception of a vigorous personality….

Her views had been refined by her travels as a lone European in remote areas, dining and sleeping in tents, during which she had observed sheikhs in their majlis, or “meeting-place,” receiving beggars, petitioners, and sycophants, judging recalcitrant tribesmen, commanding in battle, and settling vendettas.

Nor was she constrained by the stifling hierarchies of a modern bureaucracy. Bell, who ranked as a major, corresponded regularly and directly with Winston Churchill in the cabinet; Arthur Hirschel, the senior official at the India Office; Victor Chairol, the foreign editor of the Times; and Aurel Stein at the British Museum; and she had known all of them for twenty years. Many of her colleagues, including T.E. Lawrence, who came from a much more modest background than Bell, had similar access. And because of paralyzing bureaucratic rivalry in London and the distraction of the First World War (compared to the western front, the Middle East was called “a side-show of a side-show”), she and her immediate colleagues were able to champion policies in Iraq with very little interference from their theoretical superiors in the Foreign Office, the India Office, the War Office, or the Colonial Office.

This policy discussion was far more wide-ranging than the narrow establishment consensus of 2003, in which an American-led coalition pursued a poorly defined liberal democracy and ignored alternative possibilities: partition, military rule, Sharia government, reunification, or radical nationalism. Instead, Bell and her contemporaries disagreed creatively and passionately about the shape of the new state. Ibn Saud challenged its national borders, stating that the very concept of Iraq made no sense to his nomadic subjects. Bell’s colleagues, A.T. Wilson, T.E. Lawrence, and H. St. John Philby championed, respectively, with persistent and pungent conviction, a colony, an independent Arab empire, and a republic in Iraq, and resigned rather than accept a policy with which they disagreed.

Others toyed with the idea of reestablishing an Islamic caliphate; serious thought was given to an independent Assyrian Christian homeland. Bell suggested bringing in an Ottoman prince to rule Iraq and considered a proposal for an autonomous Shia region under Sharia law. They were not shy about expressing disagreement. Mark Sykes, the MP who negotiated the Sykes-Picot agreement with France to determine control of former Ottoman territory in the Middle East, described Bell as a “silly chattering windbag of conceited, gushing flat-chested, man-woman, globe-trotting, rump-wagging, blethering ass.”

Advertisement

Bell’s colleagues had many flaws. They were capable of unforgivable brutality. Colonel Gerard Leachman, one of Bell’s most prominent colleagues in the civil administration in Iraq after World War I, advocated a strategy of punitive raids that disgusted T.E. Lawrence. Winston Churchill favored using gas to attack rebellious tribesmen and launched a policy of control through aerial bombardment. Bell’s boss A.T. Wilson, who was civil commissioner in Baghdad from 1918 to 1920, may have been an impressive figure; he saved money on home leave by doing a double shift as a stoker, shoveling coal sixteen hours a day from Bombay to Marseilles and cycling the last nine hundred miles home. But he was also a sun-baked imperialist who lacked sympathy for Iraqis and the imagination to encompass their aspirations. The writings of Bell’s second boss, Percy Cox, who replaced Wilson in 1920 as first high commissioner of the newly created mandate, could be unpleasantly racist.

Bell shared many of their prejudices. As Toby Dodge’s Inventing Iraq carefully demonstrates, she and they exaggerated the despotism and corruption of Ottoman rule and blindly abolished positive aspects of Ottoman taxation and administration; at the same time their romantic admiration for tribal sheikhs encouraged the British to strengthen the sheikhs’ authority over their tribesmen at the expense of the cities and central government.1

Bell’s biographers, however, have generally ignored her intriguing combination of creativity, honesty, intelligence, and wrongheaded idiocy in favor of celebrating her as a female genius. This is in part because of her colorful life. Gertrude Bell’s father was one of the richest men in Britain. Born in 1868 and raised in Yorkshire, she won the equivalent of a first-class degree at Oxford University and learned Arabic, Persian, and Hebrew. Until she was thirty she occupied herself traveling, designing a garden, translating Persian poetry, and dining with the greatest figures in late Victorian London.

In 1899 she began serious alpine climbing in Switzerland, summiting seven “virgin” peaks in the Englehorner range, one of which is still named after her, and enduring fifty-three hours on a rope in a blizzard and extreme frostbite in her unsuccessful ascent of the northeast face of the Finsteraarhorn. She made a useful contribution to the dating of Byzantine churches, produced a detailed survey of the Abbasid castle of Ukhadair, in Iraq, and wrote a popular travel book. She fell in love with a married military hero. In 1913, she toured the Arabian peninsula, becoming one of few foreigners to survive the Nejd desert and the hostile Arabian tribes and to enter the remote city of Hail, in north-central Saudi Arabia.

This was a striking resume. It may have prepared her better for work in Iraq than a master’s degree in international relations and a career in a risk-averse bureaucracy such as the State Department or the Department of Defense. But it was not evidence of genius. Her translation of the Persian poet Hafiz is ponderous and prissy. Her expedition to the remote city of Hail yielded no significant anthropological or topographical data. Lady Ann Blunt had ridden to Hail forty years before Bell. And such adventures were not exceptional among her colleagues in Iraq, many of whom were archaeologists, scholars, or amateur spies and all of whom had undertaken long solo journeys in remote regions.

The political officers in Iraq in 1916 are best perceived not as romantic originals but as conscious servants of an imperial tradition. If Bell turned naturally to archaeology in Baghdad, it was because for a century the scholar-soldier British residents in Baghdad had been pioneers in major fields of archaeology. J.E. Taylor uncovered Sumerian civilization, Henry Rawlinson was the first to decipher cuneiform, and A.H. Layard surveyed Nineveh. If she and her colleagues undertook long hazardous journeys of exploration, wrote books, and expected to be rewarded with fame, promotion, and medals from the Royal Geographical Society or from the king, that was how Alexander Burnes, the British political officer in Afghanistan, had been rewarded on his return from Bokhara in 1832.

Yet it was also a tradition falling apart in the aftermath of World War I. In Desert Queen, Bell’s biographer Janet Wallach portrays her childhood as a repressive Victorian cliché (“she was reminded to…sit up straight, hold her knife and fork properly and speak to adults only when spoken to”). Bell’s grandfather, however, was a friend of Darwin and Huxley, her stepmother wrote brutal plays about working-class suffering, and Bell herself, a strident atheist, had absorbed 150 years of radical and revolutionary writing, which exposed the hypocrisy and injustice of colonialism. The family money came from the British steel industry; by Bell’s time, however, it was collapsing like much of British manufacturing in the face of foreign competition. She worked with a government that could not afford new colonies, a public that was not interested in them, and intellectuals who despised them.

H.V.F. Winstone’s 1978 biography, Gertrude Bell: The Lady of Iraq, is slight on Bell’s emotions and relationships. It is, however, the most assured portrait of Bell in the setting of her age. Whereas his subsequent book about Bell’s colleague Colonel Gerard Leachman is thin and ill-considered,2 his account of Bell is detailed, erudite, and thoughtful. Georgina Howell’s much more recent biography, Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations, ignores the historical background and the good academic writing on British policymaking in the Middle East after 1915 in favor of hagiography. She implies unconvincingly that Bell may have undertaken secret operations to relieve the British forces who were besieged by the Ottomans in the Iraqi city of Kut in 1916. She claims on the most flimsy evidence that Bell successfully disguised herself as an Arab beggar, led troops into battle, and endured torture. She proclaims:

One fact remains indisputable…. Gertrude Bell left behind her a benevolent and effective Iraqi government, functioning without institutionalized corruption and intent on equality and peace…. As long as Faisal lived, Iraq was a place where all its people could carry on their daily lives without fear or suffering….

The administration of Faisal, the Hashemite king of Iraq, installed in 1921 with Bell’s support, was, in reality, corrupt, inadequate, and violent, and Faisal was not beyond assassinating his opponents such as the moderate politician Taufiq al-Khalid in 1924.

Howell’s biography, however, gives the most intimate insight into the slow evolution of the relationship between Bell and the married Colonel Charles Doughty-Wylie. It is not clear where she finds the details of their first encounter in the bedroom (one hopes she did not invent them):

Unpinning her hair, she heard him knocking softly at the door, and let him in. They stood, his arms around her, her heart beating fast, then sat a little uncomfortably on the bed…. They lay down. Folded in his arms, Gertrude told him that she was a virgin [she was forty-two]. His warmth and attentive sympathy were boundless, but when he kissed her and moved closer, she stiffened, panicked, whispered “No.”

Howell is an imaginative analyst of the lovers’ correspondence. She highlights the uncertain fervor, timid evasions, and sentimental restraint in the colonel’s replies. Such detailed description of their relationship underscores the pathos of its end. In 1915, having written two letters discouraging both his wife and Bell from committing suicide, Doughty-Wylie rallies faltering troops and, armed only with a walking stick, leads them up the beaches of Gallipoli, winning a Victoria Cross and dying at the moment of victory.

Wallach’s biography, first published in 1996, suffers from clustered adjectives and ponderous clichés on historical themes. But she is the most scrupulous and patient chronicler of Bell’s daily life in Iraq. She describes Bell as an independent, wealthy celebrity, used to dealing on equal terms with cabinet ministers, experiencing claustrophobia and indignity not merely because of her treatment by colleagues in Iraq but by the routine of a military camp. Shattered by the death of her lover, Doughty-Wylie, nearing fifty, and wracked by fever in the heat of an Iraqi summer, it is hardly surprising that she broke down in tears, in the mess hall when served bully beef for the fourteenth day in a row.

Both Georgina Howell and Janet Wallach celebrate Bell’s unusual prominence in the male worlds of Oxford, climbing, exploration, and the Colonial Service. It is, therefore, surprising that neither adequately examines Bell’s decision to become the secretary of the women’s Anti-Suffrage League, campaigning against giving women the vote. How could a successful woman who so confidently appointed Iraqi politicians think herself unqualified to vote in a British election? Yet this example of an intelligent policymaker so entirely misjudging other women, herself, and the inevitable direction of history raises questions about Bell’s judgment in general.

As T.E. Lawrence harshly but accurately observed, “She was not a good judge of men or situations,” and was always “the slave” of whoever had immediate influence over her. She tended to adjust her views to fit with those whom she served, whether it was Wilson or Cox. Her political instincts were uncertain: she underestimated the threat of insurgency, for example, and encouraged the British military commanders to go on holiday on the eve of the uprising in 1920. She conveniently forgot the advice of many who opposed bringing in an alien king, and brushed aside Basra’s request for autonomy. Even her decision not to cover her head, though encouraging for Iraqi women, weakened her politically, since she was unable to talk with the senior Shia clerics, who would not meet an unveiled woman.

Our assumption that she made a good impression on her Arab interlocutors is difficult to substantiate since most Arabs did not themselves keep diaries and we have to rely on compliments made to and then reported by Bell and her friends. According to Howell she cultivated the most aristocratic sheikhs, but H. St. John Philby writes that Ibn Saud

certainly did not like her…and many a Najdi audience has been tickled to uproarious merriment by his mimicking of her shrill voice and feminine patter: “Abdul-Aziz! Abdul Aziz! Look at this, and what do you think of that?”

Finally, she must take some responsibility as the architect of an unstable Iraq in the middle of an unstable Middle East. Bell’s task was, of course, very difficult. There was no possibility outside the fantasies of the India Office for a great British Empire in the Middle East; nor for a new Ottoman Empire; nor probably for a vast independent pan-Arab state or caliphate. She had to consider the threats and interests of France, Iran, Turkey, what became Saudi Arabia, and Bolshevik Russia. Borders, therefore, needed to be drawn and it would have been difficult to avoid later problems between Iraq, Kuwait, and Iran wherever she had placed them. Her support for the alien Sunni king Faisal was not obviously misguided. An Iraqi Sunni or Shia leader might have faced equal challenges unifying the country; and although the monarchy was brutally toppled, this may not reflect something intrinsically republican in Iraq. In Jordan, Faisal’s brother’s kingdom continues to survive.

If there was no ideal solution, however, there were still clear mistakes. Bell should never have acquiesced in the inclusion of the Kurdish-dominated province of Mosul in Iraq. Rivalry between the Sunnis and Kurds was inevitable but the decision to include the Kurds was determined by British, not Iraqi, interests and in particular by oil; and it has proved of little benefit to either Iraq or the Kurds, 90 percent or more of whom want independence. It continues, moreover, to threaten the integrity of the state. Nor, probably, should she have acquiesced in making Iraq a British mandate: for this status was neither powerful enough to bring the benefits nor weak enough to avoid the opprobrium of colonialism. It conveyed responsibility without power. A good political officer should be sensitive to local opinions and aspirations, firm in political principles, farsighted, rational, and persuasive. By all these standards, Bell was a less talented political officer than T.E. Lawrence and a dozen of her contemporaries.

Bell’s most significant legacy is her magisterial government White Paper “Review of the Civil Administration in Mesopotamia”—comparable in its historical context to General Petraeus’s recent report to Congress—which was applauded by both houses of Parliament when presented to a skeptical government in 1920. She surveys with Augustan detachment the expenditures of the departments of agriculture and irrigation and the murder of her friends. She draws comparisons with the Indian land registry in 1834 and digresses into devil-worshiping, Armenian massacres, and jokes about “Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt.” She summarizes in Gibbonian rhetoric the flaws in British policy and also cites some remarkable achievements: a railway system with 27,000 staff members, district hospitals, schools for girls, and a police force. Her view is frequently unsettling. She supports imperfect solutions pursued in defiance of liberal values and human rights: compromises with warlords, punitive raids, and tribal justice. But her culture, her audience, and her background make her aspire, despite the political pressures of that moment, to tell the truth.

In this combination of ideological confidence, erudition, and concentrated rhetoric, Bell and her colleagues resemble Elizabethan courtiers. Like Edmund Spenser, John Harrington, and the Earl of Essex in Ireland in 1598–1599, however, they were ultimately unsuccessful colonists. In 1920, Sunni nationalists, Shia ayatollahs, and tribal sheikhs rose against the British. Their revolution, although suppressed, revealed to the British public as much as to Iraqis that there could be no sustainable British colony in Iraq. T.E. Lawrence was typically the first to acknowledge this:

We say we are in [Iraq] to develop it for the benefit of the world…. How long will we permit millions of pounds, thousands of imperial troops and tens of thousands of Arabs to be sacrificed on behalf of a form of colonial administration which can benefit nobody but the administrators?

Bell’s response on September 19, 1920, was more regretful but just as definite:

The agitation has succeeded. No one…would have thought of giving the Arabs such a free hand as we shall now give them—as a result of the rebellions! Whether it will be to their ultimate advantage, whether it won’t rather retard than advance the growth and development of the modern state which is what the ardent younger nationalists are out for—secondary schools, universities, technical colleges and all complete—is another question.

Some suggest today that the US failure in Iraq is due simply to lack of planning; to specific policy errors—debaathification, looting, the abolition of the army, and lack of troops; and to the absence of a trained cadre of Arabists and professional nation-builders. They should consider Bell and her colleagues, such as Colonel Leachman or Bertram Thomas, a political officer on the Euphrates. All three were fluent and highly experienced Arabists, won medals from the Royal Geographical Society for their Arabian journeys, and were greatly admired for their political work. Thomas was driven from his office in Shatra by a tribal mob. Colonel Leachman, who was famed for being able to kill a tribesman dead in his own tent without a hand lifted against him, was shot in the back in Fallujah. Bell’s defeat was slower but more comprehensive. Of the kingdom she created, with its Sunni monarch and Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish subjects, there is today no king, no Sunni government, and something close to civil war. Perhaps soon there will be no country.

Bell is thus both the model of a policymaker and an example of the inescapable frailty and ineptitude on the part of Western powers in the face of all that is chaotic and uncertain in the fashion for “nation-building.” Despite the prejudices of her culture and the contortions of her bureaucratic environment, she was highly intelligent, articulate, and courageous. Her colleagues were talented, creative, well informed, and determined to succeed. They had an imperial confidence. They were not unduly constrained by the press or by their own bureaucracies. They were dealing with a simpler Iraq: a smaller, more rural population at a time when Arab nationalism and political Islam were yet to develop their modern strength and appeal.

But their task was still impossible. Iraqis refused to permit foreign political officers to play at founding their new nation. T.E. Lawrence was right to demand the withdrawal of every British soldier and no stronger link between Britain and Iraq than existed between Britain and Canada. For the same reason, more language training and contact with the tribes, more troops and better counterinsurgency tactics—in short a more considered imperial approach—are equally unlikely to allow the US today to build a state in Iraq, in southern Afghanistan, or Iran. If Bell is a heroine, it is not as a visionary but as a witness to the absurdity and horror of building nations for peoples with other loyalties, models, and priorities.

This Issue

October 25, 2007