November 9 is one of those strange dates haunted by history. On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, signaling the collapse of the Soviet empire. The Nazis organized Kristallnacht on November 9, 1938, beginning their all-out campaign against Jews. On November 9, 1923, Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch was crushed in Munich, and on November 9, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and Germany was declared a republic. The date especially hovers over the history of Germany, but it marks great events in other countries as well: the Meiji Restoration in Japan, November 9, 1867; Bonaparte’s coup effectively ending the French Revolution, November 9, 1799; and the first sighting of land by the Pilgrims on the Mayflower, November 9, 1620.

On November 9, 2009, in the district court for the Southern District of New York, the Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers were scheduled to file a settlement to resolve their suit against Google for alleged breach of copyright in its program to digitize millions of books from research libraries and to make them available, for a fee, online. Not comparable to the fall of the Berlin Wall, you might say. True, but for several months, all eyes in the world of books—authors, publishers, librarians, and a great many readers—were trained on the court and its judge, Denny Chin, because this seemingly small-scale squabble over copyright looked likely to determine the digital future for all of us.

Google has by now digitized some ten million books. On what terms will it make those texts available to readers? That is the question before Judge Chin. If he construes the case narrowly, according to precedents in class-action suits, he could conclude that none of the parties had been slighted. That decision would remove all obstacles to Google’s attempt to transform its digitizing of texts into the largest library and book-selling business the world has ever known. If Judge Chin were to take a broad view of the case, the settlement could be modified in ways that would protect the public against potential abuses of Google’s monopolistic power.

That Google’s enterprise (Google Book Search, or GBS) threatened to become an overweening monopoly became clear when the Department of Justice filed a memorandum with the court warning about the likelihood of a violation of antitrust legislation. More than four hundred other memorandums and amicus briefs also provided warnings about mounting opposition to GBS. In the face of this opposition, Google and the plaintiffs petitioned the court to delay a hearing that was scheduled for October 17 so that they could rework the settlement. Judge Chin set November 9 as the deadline when the new version of the settlement would be unveiled.

The great event turned out to be a dud, however. At the last minute, Google and the plaintiffs asked Judge Chin to grant another extension. He gave them four more days, so the witching hour finally took place not on November 9 but on a less auspicious date, Friday the 13th.

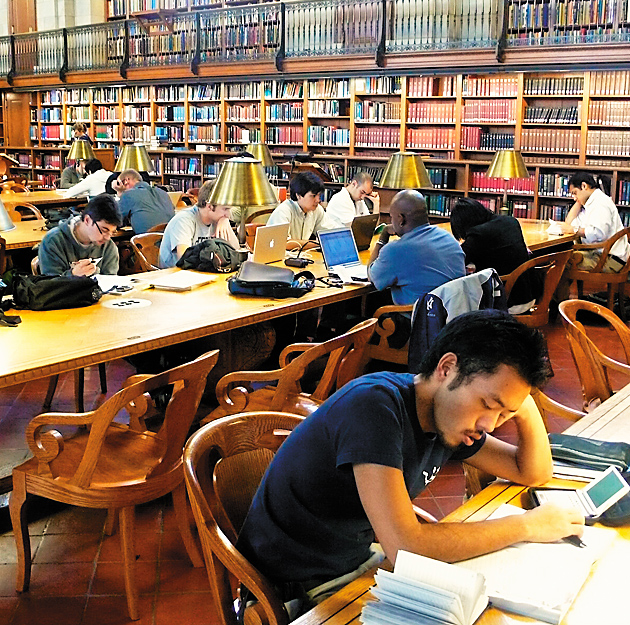

Why did the deadline look so monumental? The terms of the settlement will have a profound effect on the book industry for the foreseeable future. On the positive side, Google will make it possible for consumers to purchase access to millions of copyrighted books currently in print, and to read them on hand-held devices or computer screens, with payment going to authors and publishers as well as Google. Many millions more—books covered by copyright but out of print, at least seven million in all, including untold millions of “orphans” whose rightsholders have not been identified—will be available through subscriptions paid for by institutions such as universities. The database, along with books in the public domain that Google has already digitized, will constitute a gigantic digital library, and it will grow over time so that someday it could be larger than the Library of Congress (which now contains over 21 million catalogued books). By paying a moderate subscription fee, libraries, colleges, and educational institutions of all kinds could have instant access to a whole world of learning and literature.

But will the price be moderate? The negative arguments stress the danger that monopolies tend to charge monopoly prices. Equally important, they warn that Google’s dominance of access to books will reinforce its power over access to other kinds of information, raising concerns about privacy (Google may be able to aggregate data about your reading, e-mail, consumption, housing, travel, employment, and many other activities). The same dominance also raises questions about both competition (the class-action character of the suit could make it impossible for another entrepreneur to digitize orphan works, because only Google will be protected from litigation by rightsholders) and commitment to the public good. As a commercial enterprise, Google’s first duty is to provide a profit for its shareholders, and the settlement leaves no room for representation of libraries, readers, or the public in general.

Advertisement

An extensive argument about the pros and cons could turn Judge Chin’s courtroom into a forum where the full range of literary questions would be dramatized by debate. No courtroom drama took place on November 13, because nothing happened other than the filing of the revised settlement (call it GBS 2.0 to distinguish it from the original version of the settlement, GBS 1.0). But the filing was important in itself, because it marked the denouement of years of hard bargaining over who would control a large stretch of the digital landscape that is just now coming into view.

To be sure, GBS 2.0 will certainly be challenged by groups and individuals who claim they were not fairly represented in the classes of authors and publishers. The case may take years to work its way through the courts. Meanwhile, Google will go on digitizing; and as the legal situation evolves, it may devise further revisions of the settlement (GBS 3.0, GBS 4.0, etc.). The public will have to study all the new versions of the settlement in order to stay informed about the rules of the game while the game is being played. Who ultimately wins is not simply a matter of competition among potential entrepreneurs but an issue of enormous importance to everyone who cares about books, even though the public is reduced to the role of spectator.

As the first step toward a resolution, the filing on November 13 suggested just how far Google is willing to go in modifying the original settlement. Google’s spokesman hailed the revised version as providing all the benefits and none of the defects that one could expect. According to Dan Clancy, Google Books engineering director,

Google is still very excited about this agreement…. We look forward to continuing to work with rightsholders from around the world to fulfill our longstanding mission of increasing access to all the world’s books.

But the arguments in favor of the reworked settlement came from Google and the plaintiffs who will become its collaborators if their deal is approved. To get a sense of the counterarguments, one can survey the memorandums and amicus briefs that were filed with the court before November 9.* The protests that came from Europe are the most revealing. Although they concentrate on issues of special importance to foreigners—above all, the incompatibility of American class-action suits with protection for copyright holders who are not Americans—they show how the settlement was seen from a distant perspective.

The governments of France and Germany sent memorandums urging the court to reject the settlement “in its entirety” or at least insofar as it applied to their own citizens. Far from seeing any potential public good in it, they condemned it for creating an “unchecked, concentrated power” over the digitization of a vast amount of literature (this according to the French memorandum) and for doing so (according to the Germans) by a “commercially driven” agreement negotiated “in secrecy…behind closed doors by three interested parties, the Authors Guild, the Association of American Publishers and Google, Inc.”

In contrast to the commercial character of Google’s enterprise, both governments stressed the higher values represented by their national literatures. The French began their memorandum by invoking Pascal, Descartes, Molière, Racine, and other writers through Camus and Sartre, while the Germans summoned up the line that led from Goethe and Schiller to Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass. Each country cited the number of its Nobel Prize winners in literature (France sixteen, Germany twelve), and each buttressed its case by other evidence of high-mindedness. The Germans insisted on Gutenberg and his contribution to “the spread of science and culture.” The French cited the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen from 1789 and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 in order to uphold the principle of “free access to information” threatened by Google’s “de facto monopoly.”

It is an odd spectacle: foreign governments defending a European notion of culture against the capitalistic inroads of an American company, and submitting their case to Judge Denny Chin of the Southern District Court of New York. What Judge Chin, who grew up in Hell’s Kitchen in a family of poor Chinese immigrants (and won a scholarship to Princeton University) made of it all is difficult to say. He did not tip his hand on November 13, nor did he say when a hearing would take place.

In playing the cultural card, the French emphasized the unique character of the book, “a product unlike other products”—its power to capture creativity, to enrich civilization, and to promote diversity, which, they claimed, would be compromised by Google’s commitment to commercialization. The Germans spoke in the name of “the land of poets and thinkers,” but they laid most stress on the right of privacy, which, they argued, Google could threaten by keeping data on who reads what. Both governments then listed a series of subsidiary arguments, which were nearly the same, word for word—unsurprisingly, as they engaged the same legal counsel:

Advertisement

- The settlement gives Google a virtual monopoly over orphan works, even though it has no claim to their copyrights.

- Its opt-out provision, which means that authors will be deemed to have accepted the settlement unless they notify Google to the contrary, violates the rights inherent in authorship.

- It contains a most-favored- nation clause—i.e., a provision that prevents a potential competitor from obtaining better terms than Google in any new commercial uses of the digitized books. The terms of such future enterprises will be determined by a Books Rights Registry composed exclusively of representatives of the authors and publishers. The Registry will keep track of copyrights and cooperate with Google in setting prices.

- It gives Google the power to censor its database by excluding up to 15 percent of the digitized works.

Its guidelines for pricing will promote Google’s commercial interests, not the good of the public, through the use of algorithms created by Google according to Google’s secret methods.

It favors secrecy in general, hiding audit procedures, preventing the public from attending meetings in which Google and the Registry will discuss library matters, and even requiring Google, the authors, and publishers to destroy all documents relevant to their agreement on the settlement.

Above all, the French and Germans condemned the settlement for sanctioning the “uncontrolled, autocratic concentration of power in a single corporate entity,” which threatened the “free exchange of ideas through literature.” To drive the point home, they both noted that Google has taken in more revenue than many countries—$22 billion in 2008.

The same points were made in a hearing before the European Commission on September 7 by the three most important international library associations: the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA), the European Bureau of Library, Information and Documentation Associates (EBLIDA), and the Ligue des Bibliothèques Européennes de Recherche (LIBER). In nearly identical testimony, all three stressed the danger that “a large proportion of the world’s heritage of books in digital format will be under the control of a single corporate entity.”

It was Google’s sheer power that gave them pause. They summoned up the prospect of a digital library of 30 million books that would cost $750 million, and they concluded that Google would exercise something close to hegemony in the book world. Therefore, they appealed to the European Commission to defend the interests of the public by preventing Google from abusing its power.

Some of these associations submitted similar statements to the New York court. So did hundreds of other groups and individuals. After reading through them, one has the impression of a sense of alarm gathering force and rising to the surface of a collective consciousness. As November 9 approached, it did indeed promise to be a day of destiny, when we would begin to see into our digital future and to face the forces that might determine it.

Where was the Department of Justice in the pre-November debate? It, too, submitted a memorandum for the court’s consideration. After months of investigating potential violations of antitrust law, the DOJ pointed to two serious difficulties: the possibility of horizontal agreements among authors and publishers to restrict price competition and the further restriction of competition by Google’s de facto exclusive rights to the digital distribution of orphan works. Competitors would be denied access to millions of orphans, the memorandum argued, because they would not enjoy the immunity from suits for copyright infringement that the settlement reserves to Google. Moreover, the settlement’s equivalent of a most-favored-nation clause would prevent all competitors from obtaining better terms than Google’s even if they could put together an attractive database. Instead of expatiating in the European manner on the danger to the world’s literary heritage, the DOJ warned about something concrete: the “risk of market foreclosure.”

What to do? Far from sounding hostile to Google Book Search, the DOJ acknowledged its potential to promote the public good and announced, “The United States does not want the opportunity or momentum to be lost.” The memorandum could therefore be read as a prescription for a way to save the settlement. It concentrated on the most hotly debated provisions—those concerning the approximately seven million out-of-print but in-copyright books, especially orphans—and it suggested the following changes:

- Require rightsholders of out-of-print books to participate in the settlement by opting in instead of operating from the assumption that they had agreed to participate unless they opted out. The shift to an opt-out default would remove Google’s control of books whose rightsholders cannot be identified or do not come forward.

- Do not distribute the profits from the sale of orphan books to the parties of the settlement (Google and the authors and publishers) but rather use the money to fund a thorough search for the unknown rightsholders, and extend the search for a long period of time.

Appoint guardians to protect the interests of orphan rightsholders by serving on the registry.

Find some mechanism by which potential competitors to Google could gain access to orphan works without exposure to suits for infringement of copyright. Presumably this would require legislation by Congress.

Prevent Google from using out-of-print works in new commercial products without the owner’s permission.

The DOJ said it would continue to investigate the potential violation of antitrust laws, and it concluded with an unambiguous imperative: “This Court should reject the Proposed Settlement in its current form….” But its recommendations for an improved settlement did not go far—not nearly as far as those suggested by the governments of France and Germany and many other critics. The DOJ said nothing about the need for monitoring prices, protecting privacy, preventing censorship, providing representation of the public on the registry, and requiring full disclosure of Google’s secret data. If the DOJ encouraged Judge Chin to take a broad view of the settlement, it did not open the door wide.

The revised settlement, or GBS 2.0, released on November 13, reads as if Google and the plaintiffs took most of their cues from the DOJ’s memorandum. In a clear concession to the DOJ’s criticisms, GBS 2.0 provides that the Registry will include a court-appointed guardian to represent the rightsholders of unclaimed books. But it does not switch to an opt-out provision for such rightsholders—that is, according to GBS 2.0, any owner of a copyright of an out-of-print book would be deemed to accept the settlement unless he or she rejected it. Because millions of books, primarily orphans, fall into this category where the rightsholders are difficult to identify, Google alone would enjoy immunity from prosecution by any rightsholders who might turn up—and the exposure to litigation, which could easily reach $150,000 per title, would be enough to prevent any competitor from entering the field. Instead of providing a solution to the problem of orphan works, GBS 2.0 leaves Google in command of their commercialization, pending eventual legislation by Congress.

As to revenue from the sale of orphan books, GBS 2.0 complies with the DOJ’s insistence that the money not go to Google and the plaintiffs. Instead it will be spent in efforts to search for the unidentified rightsholders; and after being held for ten years, the funds will be distributed to charities determined by court order.

GBS 2.0 also follows the DOJ’s recommendation to abandon the most-favored-nation clause. Google’s competitors would be able to license out-of-print books in retail enterprises —that is, in selling individual works to consumers—although Google would maintain exclusive control of the institutional subscriptions to its gigantic database.

How the price of those subscriptions will be set remains unclear. GBS 2.0 has some language explaining the way its pricing algorithm will work, but it contains no effective mechanism to prevent price gouging, no provision for an antitrust consent decree that would empower a public authority to monitor prices, and no way to protect the public from excessive pricing should Google be taken over in the future by rapacious speculators.

GBS 2.0 does not therefore differ in essentials from GBS 1.0. It largely ignores the objections of foreign governments, except in one crucial respect: it partly meets the objections by narrowing the scope of GBS to books published in the United States and to countries with similar legal systems—that is, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. Google will not display books published in countries like France and Germany, and it will give them representation on the Registry to protect their interests. Just what proportion of unclaimed works will now be excluded from the settlement by this concession remains to be clarified.

Will these concessions be enough to mollify Google’s critics outside the Department of Justice who are not parties to the settlement? Probably not, judging from a statement issued on November 13 by the Open Book Alliance, whose members include Microsoft, Amazon, and Yahoo:

By performing surgical nip and tuck, Google, the AAP [Association of American Publishers], and the AG [Authors Guild] are attempting to distract people from their continued efforts to establish a monopoly over digital content access and distribution; usurp Congress’s role in setting copyright policy; lock writers into their unsought registry, stripping them of their individual contract rights; put library budgets and patron privacy at risk; and establish a dangerous precedent by abusing the class action process.

What then is the outlook for the future? No one can predict the fate of the settlement as it bounces from court to court; but if the public good should be taken into consideration, one can imagine two general solutions to the problems posed by GBS, one maximal, one minimal.

The most ambitious solution would transform Google’s digital database into a truly public library. That, of course, would require an act of Congress, one that would make a decisive break with the American habit of determining public issues by private lawsuit. The legislation would have to settle ancillary problems—how to adjust copyright, deal with orphan books, and compensate Google for its investment in digitizing—but it would have the advantage of clearing up a messy legal landscape and of giving the American people what they deserve: a national digital library equal to the needs of the twenty-first century. But it is not clear how Google would react to such a buyout.

If state intervention is deemed to go too far against the American grain, a minimal solution could be devised for the private sector. Congress would have to intervene with legislation to protect the digitization of orphan works from lawsuits, but it would not need to appropriate funds. Instead, funding could come from a coalition of foundations. The digitizing, open-access distribution, and preservation of orphan works could be done by a nonprofit organization such as the Internet Archive, a nonprofit group that was built as a digital library of texts, images, and archived Web pages. In order to avoid conflict with interests in the current commercial market, the database would include only books in the public domain and orphan works. Its time span would increase as copyrights expired, and it could include an opt-in provision for rightsholders of books that are in copyright but out of print.

The work need not be done in haste. At the rate of a million books a year, we would have a great library, free and accessible to everyone, within a decade. And the job would be done right, with none of the missing pages, botched images, faulty editions, omitted artwork, censoring, and misconceived cataloging that mar Google’s enterprise. Bibliographers—who appear to play little or no part in Google’s enterprise—would direct operations along with computer engineers. Librarians would cooperate with both in order to assure the preservation of the books, another weak point in GBS, because Google is not committed to maintaining its corpus, and digitized texts easily degrade or become inaccessible.

This digitizing process could be subsidized as part of the Obama administration’s economic stimulus, and the overall cost, spread out over ten to twenty years, would be manageable, perhaps $750 million in all. Meanwhile, Google and anyone else would be free to exploit the commercial sector. The national digital library could be composed from the holdings of the Library of Congress alone or, failing that, from research libraries that have not opened all their collections to Google.

Perhaps other solutions could be devised. If the court did not resolve the Google Book Search problem on November 13, at least it had the potential to concentrate minds and stimulate public debate. We are agreed that something must be done to improve the nation’s health. Why not do something to enrich its culture?

—November 18, 2009

This Issue

December 17, 2009

-

*

The texts of the documents can be consulted at dockets.justia.com/docket/court-nysdce/case_no-1:2005cv08136/case_id-273913. ↩