After two decades of regularly finding himself caught up in all sorts of seemingly extraneous side-passions (photocollages, operatic stage design, fax extravaganzas, homemade photocopier print runs, a controversial revisionist art-historical investigation, and a watercolor idyll), David Hockney, now age seventy-two, has finally taken to painting once again, doing so, over the past three or four years, with a vividness and a sheer productivity perhaps never before seen in his career. This recent body of work consists almost entirely of seasonal landscapes of the rolling hills, hedgerows, tree stands, valley wolds, and farm fields surrounding the somewhat déclassé onetime summer seaside resort of Bridlington, England, on the North Sea coast, where he now lives. Some are intimately scaled but many are among the largest, most ambitious canvases of his entire career.

The paintings have been widely exhibited—in London (at the Tate and the Royal Academy), in Los Angeles, a broad overview in a small museum in Germany this past summer—though not yet in New York, a situation that will be rectified in late October by a major show, his first there in ten years, slated to take up both the uptown and downtown spaces at PaceWildenstein.1 The buildup toward these shows has found Hockney busier than ever (he is still in the process of completing a dozen fresh canvases as I write), but not so busy that he hasn’t managed to become fascinated by yet another new (and virtually diametrically opposite) technology, one that he is pursuing with almost as much verve and fascination: drawing on his iPhone.

Hockney first became interested in iPhones about a year ago (he grabbed the one I happened to be using right out of my hands). He acquired one of his own and began using it as a high-powered reference tool, searching out paintings on the Web and cropping appropriate details as part of the occasional polemics or appreciations with which he is wont to shower his friends.

But soon he discovered one of those newfangled iPhone applications, entitled Brushes, which allows the user digitally to smear, or draw, or fingerpaint (it’s not yet entirely clear what the proper verb should be for this novel activity), to create highly sophisticated full-color images directly on the device’s screen, and then to archive or send them out by e-mail. Essentially, the Brushes application gives the user a full color-wheel spectrum, from which he can choose a specific color. He can then modify that color’s hue along a range of darker to lighter, and go on to fill in the entire backdrop of the screen in that color, or else fashion subsequent brushstrokes, variously narrower or thicker, and more or less transparent, according to need, by dragging his finger across the screen, progressively layering the emerging image with as many such daubings as he desires.2

Over the past six months, Hockney has fashioned literally hundreds, probably over a thousand, such images, often sending out four or five a day to a group of about a dozen friends, and not really caring what happens to them after that. (He assumes the friends pass them along through the digital ether.) These are, mind you, not second-generation digital copies of images that exist in some other medium: their digital expression constitutes the sole (albeit multiple) original of the image.

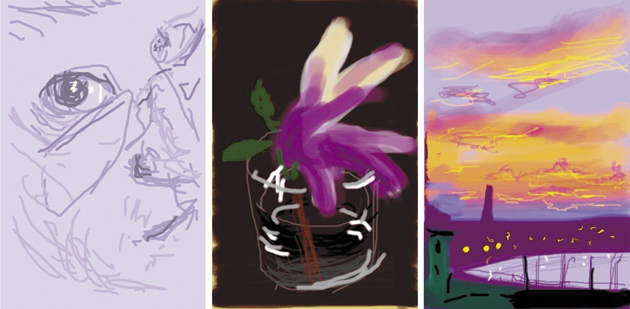

The flood of images has more or less resolved itself into three streams. To begin with, portraits, and mainly self-portraits at that—perhaps playing on the way that an iPhone’s blackened screen, when off, already functions as a sort of Claude Lorrain–style darkened glass, reflecting back a ghostly image of the user’s face. (Intriguingly, the reflected face in the blackened screen is approximately twice the size of the same face if one turns the iPhone around to snap a photographic self-portrait. “But that’s how it always is with photography,” Hockney points out. “It inevitably pushes the world away. That’s just one of its many problems.” Hockney’s drawings, as it were, bring the face back to full scale.)

Early on, however, Hockney became much more interested in bunches of cut flowers and plants ranged in brick pots, ceramic vases, and glass jars. These became the occasion for his extensive investigations into the types of effects possible in this new medium. “Although the actual drawing, when I do it, goes quite quickly,” he explains, “some days it might be preceded by hours and hours of thinking through just how one might achieve a certain play of light, texture, or color.” Indeed, the range of results is dazzlingly various, colorful, and instantaneously evocative.

Increasingly, over the past several months, it is the summer dawn, rising over the seabay outside his bedroom window, that has been capturing Hockney’s attention. “I’ve always wanted to be able to paint the dawn,” Hockney explains.

Advertisement

After all, what clearer, more luminous light are we ever afforded? Especially here where the light comes rising over the sea, just the opposite of my old California haunts. But in the old days one never could, because, of course, ordinarily it would be too dark to see the paints; or else, if you turned on a light so as to be able to see them, you’d lose the subtle gathering tones of the coming sun. But with an iPhone, I don’t even have to get out of bed, I just reach for the device, turn it on, start mixing and matching the colors, laying in the evolving scene.

He has now accomplished dozens of such sequential studies, sending them out in real time, so that his friends in America wake to their own account of the Bridlington dawn—two, five, sometimes as many as eight successive versions, sent out minutes apart, one after the next.

I’ve noticed that most users of the Brushes application tend to trace out their brushstrokes with their pointer finger. (The screen measures changes in electrical charge, and can be operated only with a conductive object—like a finger—rather than a pen-like stylus.) As I discovered on a recent visit, Hockney limits his contact with the screen exclusively to the pad of his thumb. “The thing is,” Hockney explains, “if you are using your pointer or other fingers, you actually have to be working from your elbow. Only the thumb has the opposable joint which allows you to move over the screen with maximum speed and agility, and the screen is exactly the right size, you can easily reach every corner with your thumb.” He goes on to note how people used to worry that computers would one day render us “all thumbs,” but it’s incredible the dexterity, the expressive range, lodged in “these not-so-simple thumbs of ours.”

Hockney, who has carried small notebooks in his pockets since his student days, along with pencils, crayons, pastel sticks, ink pens, and watercolor bottles—and smudged clean-up rags—is used to working small, but he delights in the simplicity of this new medium:

It’s always there in my pocket, there’s no thrashing about, scrambling for the right color. One can set to work immediately, there’s this wonderful impromptu quality, this freshness, to the activity; and when it’s over, best of all, there’s no mess, no clean-up. You just turn off the machine. Or, even better, you hit Send, and your little cohort of friends around the world gets to experience a similar immediacy. There’s something, finally, very intimate about the whole process.

I asked Hockney whether he’d mind my sharing some of these images with a wider audience across a printed medium, and he said, not really, he more or less assumed that the pictures would one by one find their way into the world. “Though it is worth noting,” he adds, lighting one of his perennial cigarettes, “that the images always look better on the screen than on the page. After all, this is a medium of pure light, not ink or pigment, if anything more akin to a stained glass window than an illustration on paper.” He continues:

It’s all part of the urge toward figuration. You look out at the world and you’re called to make gestures in response. And that’s a primordial calling: goes all the way back to the cave painters. May even have preceded language. People are always asking me about my ancestors, and I say, Well there must have been a cave painter back there somewhere. Him scratching away on his cave wall, me dragging my thumb over this iPhone’s screen. All part of the same passion.

He laughs, stubs out his cigarette, snaps off the iPhone, and heads back over to a vast set of painted canvases arrayed against the far wall of his hangarlike studio: a view of a forest road lined with felled trees, a gridded combine of fifteen canvases, three high and five long. He daubs a long paintbrush with fresh creamy glops of paint, and begins working from his shoulder. “People from the village,” he says, craning back over that shoulder, “come up to me and tease me, ‘We hear you’ve started drawing on your telephone.’ And I tell them, ‘Well, no, actually, it’s just that occasionally I speak on my sketch pad.'”

This Issue

October 22, 2009