Epics, with their heroic memories, are necessarily composed in changing times. The Iliad and the Odyssey commemorate a Bronze Age culture that had collapsed half a millennium earlier; the poems themselves signal an entirely new, recognizably classical Greece. Vergil’s Aeneid, penned at the very beginning of the Roman Empire, focuses less on the founding of Rome than it does on the end of Troy. Götterdämmerung speaks for itself; tales of the gods’ twilight cannot be told until we are well into the night. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is a sustained elegy for the time when wilderness was the dominant condition of the world, and the crags, plants, and creatures in wild places were magical because the whole earth was magical—a Britain before motorways.

Ludovico Ariosto’s epic Orlando Furioso is no exception to this elegiac list; he composed his Italian vernacular version of the medieval Chanson de Roland well into the Italian Renaissance; it may have been the best-selling work of fiction in the sixteenth century. The first edition of Orlando Furioso was printed (still a relatively new phenomenon) in 1516, but Ariosto continued to work on the project for the rest of his life, adding, editing, and rewriting. His latest version, from 1532, extends over forty-six cantos of 72 to 192 eight-line stanzas; in one recent Italian edition this means precisely 750 pages of very fine print. Yet despite its monumental length, its heroic subjects, and its atmosphere of changing times, Orlando Furioso is anything but elegiac in its tone; it is the sixteenth-century version of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, a send-up with biting social commentary, outrageous adventures, over-the-top violence, a sexual merry-go-round, and humor at every level from the most refined to the most sophomoric. Most Renaissance jokes are as lame after five centuries as their modern equivalents will prove to be, but Ariosto can still make anyone laugh.

He was not the first Italian writer to parody chivalric romance; the Florentine poet Luigi Pulci had already sent up the Chanson de Roland in 1478 and 1483 with successive versions of his Morgante, which takes its title from a pagan giant converted by Roland to Christianity. Matteo Maria Boiardo followed a decade later with Orlando Innamorato (“Roland in Love,” first published in 1495), which he didn’t live to finish. Ariosto took on the task of finishing Boiardo’s story, which fits Roland into his real tale: the romance of the female warrior Bradamante and the Italian knight Ruggiero, a descendant of the Trojan hero Hector, the mythic ancestors of the house of d’Este.

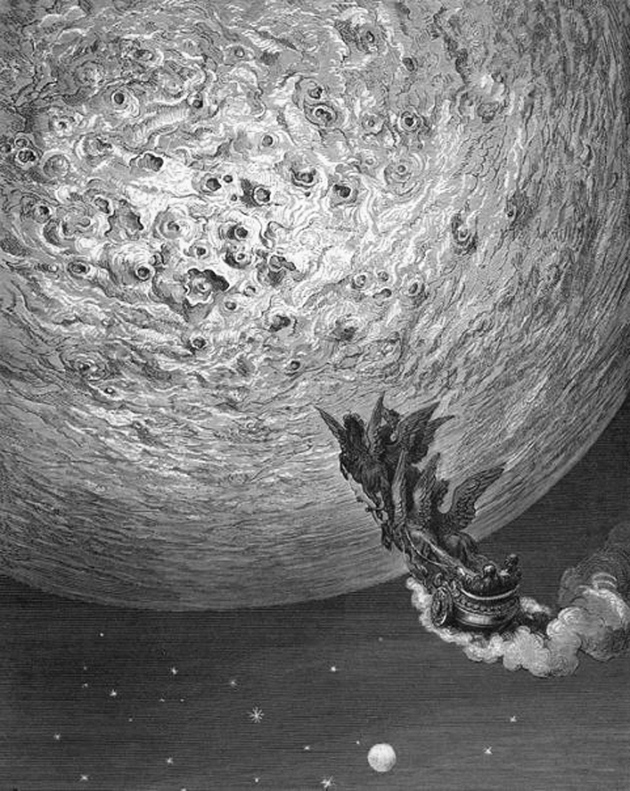

All these poems used ottava rima, the meter of ballads, eight-line stanzas rhymed according to a strict pattern (ABABABCC) and gathered in cantos. Ariosto, too, exults in fantastic creatures like Morgante, and uses a light touch with the heroic past, along with some appropriately modern details: the action, mostly set outside Paris, moves as far away for some episodes as Japan and the moon. Orlando’s beloved Angelica comes from a kingdom near Cathay, somewhere near Bishkek, Irkutsk, or Ulan Bator, and she is not the only exotic foreigner: the cast of Orlando Furioso is a triumph of diversity. Nearly everyone has an enchanted weapon or enchanted armor, some pieces handed down through Hector from the Trojan War. But Ariosto also knows all about guns.

Like Morgante, which was composed for the amusement of Lorenzo de’ Medici and his friends, and Orlando Innamorato, composed for Ercole d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, Orlando Furioso was also written for an aristocratic sponsor: Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, Ercole’s son and younger brother of the reigning duke, Alfonso d’Este. As professional soldiers and feudal landholders, the d’Este males still ostensibly subscribed to an ideal of chivalry, but theirs was a chivalry faced with a series of challenges, from gunpowder artillery to the modern nation-state, that would soon make traditional knighthood hopelessly obsolete. Ariosto composed Orlando Furioso, after all, when Machiavelli was busy writing The Prince.

Alfonso d’Este was the first Italian military leader to use gunpowder artillery, in 1510, against Pope Julius II, who confronted Alfonso, his nominal and disobedient vassal, in full armor and an enormous fur hat. Orlando Furioso sings the praises of Alfonso’s cannon, but it is worth noting that Julius eventually won what is now known as the Ferrara Salt War, by resorting to a weapon still more powerful and more avant-garde than guns: economics. The Church had more money than Alfonso; furthermore, Julius was happy to excommunicate Alfonso until he finally saw the light in 1512.

Both Alfonso and Ippolito d’Este appreciated the fact that their court poet was fully attuned to the new Machiavellian ways of thinking, and to the eternal vagaries of human nature; for decades, therefore, they employed Ariosto as a diplomat in addition to his duties as poet laureate. Among northern Italian feudal courts—city-states ruled by warlords—Ferrara emerged from the Middle Ages as more progressive than most of its neighbors, perhaps because of its proximity to republican Venice (Ferrara sits alongside the Po River just before its delta opens out into the Venetian lagoon). Like Venice, Ferrara had a thriving Jewish community; its university had been quick to adopt the new curriculum of “humane studies” already in the fifteenth century, and like the nearby University of Padua it would quickly embrace the new sciences (hosting the likes of Leoniceno, Paracelsus, and Copernicus).

Advertisement

The bright red brick of the d’Este palace, sitting neatly behind its moat, is considerably less grim than the huge, dark brick façade of the ducal palace in Mantua, where Alfonso and Ippolito’s sister Isabella d’Este lived with her husband, Francesco Gonzaga. The Gonzaga palace has iron cages fixed to its walls high above the piazza in which prisoners could be exposed to the scorn of the elements and the public. Ferrara had its vicious intrigues, too, but Alfonso’s wife, Lucrezia Borgia, unlike haughty Isabella, was a kind soul. When Alfonso and Ippolito’s illegitimate half-brothers Giulio and Ferrante d’Este conspired against the duke and his brother in 1506, she managed to commute their capital sentence to imprisonment in a tower of the palace. Ferrante died in confinement in 1540, but Giulio was finally released in 1559 at the age of eighty-one. He had spent fifty-three years in captivity, and was a handsome old man who wandered the streets of Ferrara for the next two years in total freedom, still dressed in the same clothing as half a century before.

Ferrara was also a musical center. Poets since Petrarch routinely described their activity as “singing,” just as the Greek and Latin poets had done. We should probably take that description literally. Composers vied with one another to set Petrarch’s sonnets to music, and Ariosto, with his ottava rima, deliberately follows the tradition of the troubadours and their ballads. When he comes to the end of a canto (a term that meant “song”), he bids Ippolito to “hear,” not to “read,” what happens next.

David Slavitt’s translation is the first to appear for some time in rhymed English verse. The transition from Italian to English is not always easy to make: Italian, richer in vowels and inflected endings than English, is infinitely easier to rhyme, but English compensates in part for that difficulty by its wealth of vocabulary, often with alternatives from both Latin and Anglo-Saxon roots. At least since the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, who was himself an avid translator from Italian, English poets have composed in iambic pentameter, which tends to follow the natural rise and fall of colloquial speech, and is as close as English can get to Italian ottava rima. Typically, therefore, both Sir Philip Sidney and William Shakespeare borrowed the rhyming scheme of Petrarch’s sonnets, but did so in iambic pentameter. Slavitt, too, has chosen this time-honored, quintessentially English meter, while preserving the pattern of Ariosto’s rhyme and allowing himself the liberties that Ariosto takes with the basic form.

The argument for translating poetry as poetry is simple: the poetic discipline is as much a part of the poem’s content as the story it tells. Thus Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf preserves the rules of Anglo-Saxon alliterative poetry intact and alters only the poem’s ancient, barely intelligible vocabulary. The work of translation becomes far more of a problem when poetic strictures are radically different between languages. This is the case with the poets of ancient Greece and Rome, and with the Bible. The Greeks and Romans used quantitative verse, based on patterns of long and short vowels. The natural stresses of words were less important than the nature of their vowel sounds, and rhyme was unimportant altogether.

This situation changed in the Middle Ages, when Latin and vernacular verse began to mark out meter through word accent rather than vowel quantity and the ends of poetic lines began to rhyme. Thus the rhymed, rhythmic heroic couplets that John Dryden used to translate Vergil’s Aeneid are just as alien to ancient versification as the looser varieties of blank verse that Richmond Lattimore, Robert Fagles, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Allen Mandelbaum have invented more recently to render the dactylic hexameters of Homer and Vergil.

With Dante, Petrarch, and Ariosto, however, Italian rhyme and meter hew fairly close to traditional English forms, not least because those forms were originally adapted to English by writers steeped in Italian poetry. The basic problem with verse translation, however, is maintaining its quality: to suggest poetry rather than doggerel. The line between these two categories is not always easy to draw, even in Shakespeare and Keats. Dryden’s Vergil is magnificent, in part because the poetic language is natural poetic language for Dryden’s time.

Advertisement

Verse translation became far more complicated for translators in the early twentieth century, in part because poets were experimenting with other forms and definitions of poetry, but also because of the efforts of two eminent English classicists. Matthew Arnold’s essay “On Translating Homer” (1861), written to skewer F.W. Newman’s verse translation of the Iliad, raised the standards for verse translation to dizzying new heights:

Between Cowper and Homer there is interposed the mist of Cowper’s elaborate Miltonic manner, entirely alien to the flowing rapidity of Homer; between Pope and Homer there is interposed the mist of Pope’s literary artificial manner, entirely alien to the plain naturalness of Homer’s manner; between Chapman and Homer there is interposed the mist of the fancifulness of the Elizabethan age, entirely alien to the plain directness of Homer’s thought and feeling; while between Mr. Newman and Homer is interposed a cloud of more than Egyptian thickness—namely, a manner, in Mr. Newman’s version, eminently ignoble, while Homer’s manner is eminently noble.

In 1883, A.E. Housman lambasted English versions of Aeschylus (and Aeschylus himself) by parodying them mercilessly in his “Fragment of a Greek Tragedy”:

CHORUS: O suitably-attired-in-leather-boots

Head of a traveller, wherefore seeking whom

Whence by what way how purposed art thou come

To this well-nightingaled vicinity?

My object in inquiring is to know.

But if you happen to be deaf and dumb

And do not understand a word I say,

Then wave your hand, to signify as much.

ALCMAEON: I journeyed hither by a Boeotian road.

CHORUS: Sailing on horseback, or with feet for oars?

From 1949 to her death in 1957, Dorothy Sayers, undaunted by the dons, attempted to put all of Dante’s Divine Comedy into English terza rima, doing a decent job of it, too, so much so that her version is still in print. It has begun, inevitably, to take on a patina of age, one of the reasons that translations keep coming, generation after generation:

The morn was young, and in his native sign

The Sun climbed with the stars whose glitterings

Attended on him when the Love Divine

First moved those happy, prime-created things:

So the sweet season and the new-born day

Filled me with hope and cheerful augurings

Of the bright beast so speckled and so gay;

Yet not so much but that I fell to quaking

At a fresh sight—a Lion in the way.

For a certain period, literary modernists (writing in Matthew Arnold’s most pontifical mode) insisted that metrical poetry was no longer possible in English, but poets continued to write in meter anyway, and readers continued to appreciate their efforts. Slavitt’s choice of verse recognizes the continuing power of verse. Furthermore, he comes to this project after having translated Greek and Roman classics (indeed, he has translated dozens of works); thus his own background, as reader and translator, incorporates Ariosto’s own literary roots. He has opted for what he describes as a loose translation in very loose iambic pentameter, with an emphasis on contemporary vocabulary, and no hesitation at expressing recognizably contemporary attitudes.

Slavitt has good reasons for his choices. For a work as long as Orlando Furioso, with its thousands of stanzas galloping along at an inexorable clip, Ariosto resorts to a host of poetic expedients, letting accentuation run counter to the meter’s natural rhythm, artificially lengthening or shortening words (tôr for togliere), stretching the rules of rhyme. Slavitt, therefore, is fully justified in taking huge, occasionally egregious, liberties with his own iambics—doing otherwise, he could argue, would lose the fast-and-loose quality of the original.

Ariosto also maintains a certain authorial detachment toward his epic, a stance that Slavitt transposes into a contemporary sense as evident pleasure in one’s own cleverness. Ariosto himself was by profession a gentleman and a diplomat in a highly formal age. There is a decorous reticence to his authorial persona as well as sprezzatura, the Italian art of working hard to give the impression of ease. The attitude of Slavitt’s Ariosto is more overtly self-conscious than the elegant, contrapposto stance—i.e., the “counterpoised” attitude of ancient statues: one arm and one leg bent, the other straight, hips slanting in one direction, shoulders in the other—of a sixteenth-century Italian courtier, and hence Slavitt has made a translation of manner as well as substance; but his seemingly casual asides are anything but casual—the translation itself is a masterpiece of sprezzatura. Slavitt has been impeccably careful, but he has also had an extravagantly good time.

Here, as a measure of his diligence, is John Harington’s opening to Orlando Furioso, a translation commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I and published in 15911:

Of Dames, of Knights, of armes, of loves delight,

Of courtesies, of high attempts I speake,

Then when the Moores transported all their might

On Africke seas, the force of France to breake:

Incited by the youthfull heate and spight

Of Agramant their King, that vow’d to wreake

The death of King Trayano (lately slaine)

Upon the Romane Emperour Charlemaine.

I will no lesse Orlandos acts declare,

(A tale in prose ne verse yet sung or said)

Who fell bestraught with love, a hap most rare,

To one that erst was counted wise and stayd:

If my sweet Saint that causeth my like care,

My slender muse affoord some gracious ayd,

I make no doubt but I shall have the skill.

As much as I have promist to fulfill.

And here is Slavitt:

Of ladies, knights, of passions and of wars,

of courtliness, and of valiant deeds I sing

that took place in that era when the Moors

crossed the sea from Africa to bring

such troubles to France. I shall tell of the great stores

of rage in the heart of Agramant, the king

who swore revenge on Charlemagne who had

murdered King Troiano (Agramant’s dad).

Orlando, as well, I’ll celebrate, setting down

what has not yet been told in verse or prose—

how love drove him insane, who had been known

before as wise and prudent (like me, God knows,

until I, too, went half mad with my own

love-folly that makes it so hard to compose

in ottava rima. I pray I find the strength

to write this story in detail and at length).

The translation is more literal than it may look on its apparently colloquial surface. Here is the line-by-line content of Ariosto’s first stanza:

Of ladies, of knights, of arms and of love

Of chivalry I sing, of the audacious enterprises

That happened at the time the Moors crossed

The sea of Africa, and did so much harm in France

Following the rage and youthful furies

Of Agramant their king, who boasted

That he would avenge the death of Troiano

On Charlemagne the Roman emperor.

And here is Guido Waldman’s prose Ariosto of 1974:

I sing of knights and ladies, of love and arms, of courtly chivalry, of courageous deeds—all from the time when the Moors crossed the sea from Africa and wrought havoc in France.

For readers unfamiliar with Ariosto’s endless cast of characters, Slavitt’s “Agramant’s dad” supplies information that is normally in a footnote. The phrase sounds more informal in English than in Ariosto’s vernacular, which is not his own Ferrarese but Tuscan, the sixteenth century’s standard dialect. Tuscans today are far more likely to use the affectionate babbo rather than padre when talking about fathers; “dad” is the right equivalent—for today. In Ariosto’s day, “Signor Padre” and “Madonna Madre” were the norm.

As for the eruption of Ariosto’s own love life into the second stanza, Harington’s “sweet saint” is pure invention: Ariosto says “she” who “almost made me” as crazy as Orlando. Barbara Reynolds renders the lines clearly in her verse translation of 1973 (her Penguin edition, with her introduction, has been in print since 1975). Reynolds’s language is much more formal than Slavitt’s, and it is a tour de force in its own way:

Of ladies, cavaliers, of love and war,

Of courtesies and of brave deeds I sing,

in times of high endeavor where the Moor

Had crossed the sea from Africa to bring

Great harm to France, when Agamante swore

In wrath, being now the youthful Moorish king,

To avenge Troiano, who was lately slain,

Upon the Roman Emperor Charlemagne.

And of Orlando I will also tell

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme,

Of the mad frenzy that for love befell

One who so wise was held in former time,

If she who my poor talent by her spell

Has so reduced that I resemble him,

Will grant me now sufficient for my task;

The wit to reach the end is all I ask.

Slavitt’s verse sounds wild and crazy by comparison. The real question, in the end, is how we are to take Ariosto himself. How outrageous is he? And how much is he, in his sobriety and/or his outrageousness, a creature of sixteenth-century Ferrara, and how much is his epic, like Thucydides’ History, “an acquisition for all time”?

In many ways Ariosto is just like Euripides, a writer who appears at the end of a tradition, unable to resist sending that tradition up by bringing on dragons, wild creatures, exotic foreigners, and wild twists of plot, and yet at the same time as sincerely devoted to his craft, and his Muse, as Sophocles or Tasso. Often Ariosto’s Italian has the wry neatness that Reynolds captures so well, especially in her concluding couplets, and sometimes he takes Slavitt’s mad chances with structure and decorum. One thing is certain, however. This new Orlando Furioso, however provocative if may be on its surface, is thoroughly under control.

All told, then, it is bound to succeed in its stated effort both to attract and to stimulate discussion among student readers. Slavitt has translated a little over half the latest version of Ariosto’s epic, more than enough to provide the flavor of sixteenth-century chivalry for readers of the twenty-first.

Those Renaissance knights and ladies knew a thing or two, and so did their author. Seldom (outside Monty Python and the Holy Grail) have the contradictions of knighthood been laid so bare, from the useless violence of constant jousting to the confusing mores of aristocratic society: the cult of virginity is praised to the heavens, but that fact stops few of Ariosto’s knights and ladies from sporting vigorously. With two women warriors, Bradamante and Marfisa, the episodes of gender- bending are many and various, most of them also extremely funny, with the confusions resolved gently in private rather than in a Homeric festival of mockery.

Ariosto’s conventions do not allow the genial resolution of the Monty Python musical Spamalot, when Sir Lancelot leaps out of the chivalric closet and claims his fey prince in a burst of 1980s disco music, but the characters in Orlando Furioso clearly know all the ins and outs of eros; these were the years not only of Machiavelli, but also of I modi, the series of sexy prints executed in 1524 by Giulio Romano, engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, and published with obscene sonnets by Pietro Aretino. Orlando Furioso must be the only epic, moreover, in which the hero appears for most of its considerable length stark raving naked—definitely not in heroic nudity.

Ariosto’s afterlife ranges from Handel operas to Sicilian puppet shows, many of whose characters are drawn from Orlando Furioso, but perhaps the most poignant legacy comes from the island of Crete, a Venetian possession from 1206 to 1667. Here, in about 1600, the nobleman Vintzentzos Kornaros—in Venice he was known as Vincenzo Cornaro—wrote the poem Erotokritos, at 5,125 lines by far the longest work of poetry to emerge from the “Cretan Renaissance.” By the sixteenth century, the island’s Venetian conquerors had long since become entirely assimilated to Byzantine culture while still retaining close ties to Italy, and the Greek population had adopted Italian influences in everything from their pronunciation to their aesthetic tastes.

Cretan icons of the period are a combustible combination of Byzantine Orthodox tradition and the innovations of the Italian Renaissance; indeed, one Cretan icon painter, Domenikos Theotokopoulos, would move to Venice and then on to Spain, where he developed a unique, greatly beloved style as “El Greco.” Kornaros, like El Greco, belonged to two worlds: he was entirely assimilated into Greek culture, but he also retained Venetian tastes and Venetian attitudes (he and his brother founded a literary academy in Candia, today’s Iraklion, the capital of Crete). His poem is written in the contemporary Greek meter of Byzantine “political verse”: rhymed couplets in iambic heptameter.

The poem may always have been accompanied by music, and particularly by the stringed instrument known as the lyra—what sixteenth-century Italians called the viola da braccio. Certainly it has been passed down for centuries as song, and Cretans still know its most dramatic passages by heart.2 Erotokritos is much more somber in tone than Orlando Furioso—Crete was a rugged place, and still is—and its central romance, between the princess of Athens, Aretousa, and Erotokritos, son of the captain of the royal guard, crosses boundaries of class as only a Venetian republican could do in 1600. Like all true epics, Erotokritos is a song of changing times; two generations after its composition, the Venetians had been driven from Crete by the Ottoman Turks.

This Issue

December 23, 2010

-

1

Harington also developed a flush toilet. Thomas Crapper only applied that invention on an industrial scale. ↩

-

2

There are several versions available on YouTube; for the late Nikos Xilouris, a Cretan musician who died of cancer at the age of forty-three in 1980, Erotokritos, passed down by Greeks under Ottoman rule, recalled his own experience of Nazi occupation and then the dictatorship of the colonels who ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974. ↩