1.

It might sound odd to say this about something people deal with at least three times a day, but food in America has been more or less invisible, politically speaking, until very recently. At least until the early 1970s, when a bout of food price inflation and the appearance of books critical of industrial agriculture (by Wendell Berry, Francis Moore Lappé, and Barry Commoner, among others) threatened to propel the subject to the top of the national agenda, Americans have not had to think very hard about where their food comes from, or what it is doing to the planet, their bodies, and their society.

Most people count this a blessing. Americans spend a smaller percentage of their income on food than any people in history—slightly less than 10 percent—and a smaller amount of their time preparing it: a mere thirty-one minutes a day on average, including clean-up. The supermarkets brim with produce summoned from every corner of the globe, a steady stream of novel food products (17,000 new ones each year) crowds the middle aisles, and in the freezer case you can find “home meal replacements” in every conceivable ethnic stripe, demanding nothing more of the eater than opening the package and waiting for the microwave to chirp. Considered in the long sweep of human history, in which getting food dominated not just daily life but economic and political life as well, having to worry about food as little as we do, or did, seems almost a kind of dream.

The dream that the age-old “food problem” had been largely solved for most Americans was sustained by the tremendous postwar increases in the productivity of American farmers, made possible by cheap fossil fuel (the key ingredient in both chemical fertilizers and pesticides) and changes in agricultural policies. Asked by President Nixon to try to drive down the cost of food after it had spiked in the early 1970s, Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz shifted the historical focus of federal farm policy from supporting prices for farmers to boosting yields of a small handful of commodity crops (corn and soy especially) at any cost.

The administration’s cheap food policy worked almost too well: crop prices fell, forcing farmers to produce still more simply to break even. This led to a deep depression in the farm belt in the 1980s followed by a brutal wave of consolidation. Most importantly, the price of food came down, or at least the price of the kinds of foods that could be made from corn and soy: processed foods and sweetened beverages and feedlot meat. (Prices for fresh produce have increased since the 1980s.) Washington had succeeded in eliminating food as a political issue—an objective dear to most governments at least since the time of the French Revolution.

But although cheap food is good politics, it turns out there are significant costs—to the environment, to public health, to the public purse, even to the culture—and as these became impossible to ignore in recent years, food has come back into view. Beginning in the late 1980s, a series of food safety scandals opened people’s eyes to the way their food was being produced, each one drawing the curtain back a little further on a food system that had changed beyond recognition. When BSE, or mad cow disease, surfaced in England in 1986, Americans learned that cattle, which are herbivores, were routinely being fed the flesh of other cattle; the practice helped keep meat cheap but at the risk of a hideous brain-wasting disease.

The 1993 deaths of four children in Washington State who had eaten hamburgers from Jack in the Box were traced to meat contaminated with E.coli 0157:H7, a mutant strain of the common intestinal bacteria first identified in feedlot cattle in 1982. Since then, repeated outbreaks of food-borne illness linked to new antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria (campylobacter, salmonella, MRSA) have turned a bright light on the shortsighted practice of routinely administering antibiotics to food animals, not to treat disease but simply to speed their growth and allow them to withstand the filthy and stressful conditions in which they live.

In the wake of these food safety scandals, the conversation about food politics that briefly flourished in the 1970s was picked up again in a series of books, articles, and movies about the consequences of industrial food production.Beginning in 2001 with the publication of Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation, a surprise best-seller, and, the following year, Marion Nestle’s Food Politics, the food journalism of the last decade has succeeded in making clear and telling connections between the methods of industrial food production, agricultural policy, food-borne illness, childhood obesity, the decline of the family meal as an institution, and, notably, the decline of family income beginning in the 1970s.

Advertisement

Besides drawing women into the work force, falling wages made fast food both cheap to produce and a welcome, if not indispensible, option for pinched and harried families. The picture of the food economy Schlosser painted resembles an upside-down version of the social compact sometimes referred to as “Fordism”: instead of paying workers well enough to allow them to buy things like cars, as Henry Ford proposed to do, companies like Wal-Mart and McDonald’s pay their workers so poorly that they can afford only the cheap, low-quality food these companies sell, creating a kind of nonvirtuous circle driving down both wages and the quality of food. The advent of fast food (and cheap food in general) has, in effect, subsidized the decline of family incomes in America.

2.

Cheap food has become an indispensable pillar of the modern economy. But it is no longer an invisible or uncontested one. One of the most interesting social movements to emerge in the last few years is the “food movement,” or perhaps I should say “movements,” since it is unified as yet by little more than the recognition that industrial food production is in need of reform because its social/environmental/public health/animal welfare/gastronomic costs are too high.

As that list suggests, the critics are coming at the issue from a great many different directions. Where many social movements tend to splinter as time goes on, breaking into various factions representing divergent concerns or tactics, the food movement starts out splintered. Among the many threads of advocacy that can be lumped together under that rubric we can include school lunch reform; the campaign for animal rights and welfare; the campaign against genetically modified crops; the rise of organic and locally produced food; efforts to combat obesity and type 2 diabetes; “food sovereignty” (the principle that nations should be allowed to decide their agricultural policies rather than submit to free trade regimes); farm bill reform; food safety regulation; farmland preservation; student organizing around food issues on campus; efforts to promote urban agriculture and ensure that communities have access to healthy food; initiatives to create gardens and cooking classes in schools; farm worker rights; nutrition labeling; feedlot pollution; and the various efforts to regulate food ingredients and marketing, especially to kids.

It’s a big, lumpy tent, and sometimes the various factions beneath it work at cross-purposes. For example, activists working to strengthen federal food safety regulations have recently run afoul of local food advocates, who fear that the burden of new regulation will cripple the current revival of small-farm agriculture. Joel Salatin, the Virginia meat producer and writer who has become a hero to the food movement, fulminates against food safety regulation on libertarian grounds in his Everything I Want to Do Is Illegal: War Stories From the Local Food Front. Hunger activists like Joel Berg, in All You Can Eat: How Hungry Is America?, criticize supporters of “sustainable” agriculture—i.e., producing food in ways that do not harm the environment—for advocating reforms that threaten to raise the cost of food to the poor. Animal rights advocates occasionally pick fights with sustainable meat producers (such as Joel Salatin), as Jonathan Safran Foer does in his recent vegetarian polemic, Eating Animals.

But there are indications that these various voices may be coming together in something that looks more and more like a coherent movement. Many in the animal welfare movement, from PETA to Peter Singer, have come to see that a smaller-scale, more humane animal agriculture is a goal worth fighting for, and surely more attainable than the abolition of meat eating. Stung by charges of elitism, activists for sustainable farming are starting to take seriously the problem of hunger and poverty. They’re promoting schemes and policies to make fresh local food more accessible to the poor, through programs that give vouchers redeemable at farmers’ markets to participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and food stamp recipients. Yet a few underlying tensions remain: the “hunger lobby” has traditionally supported farm subsidies in exchange for the farm lobby’s support of nutrition programs, a marriage of convenience dating to the 1960s that vastly complicates reform of the farm bill—a top priority for the food movement.

The sociologist Troy Duster reminds us of an all-important axiom about social movements: “No movement is as coherent and integrated as it seems from afar,” he says, “and no movement is as incoherent and fractured as it seems from up close.” Viewed from a middle distance, then, the food movement coalesces around the recognition that today’s food and farming economy is “unsustainable”—that it can’t go on in its current form much longer without courting a breakdown of some kind, whether environmental, economic, or both.

Advertisement

For some in the movement, the more urgent problem is environmental: the food system consumes more fossil fuel energy than we can count on in the future (about a fifth of the total American use of such energy) and emits more greenhouse gas than we can afford to emit, particularly since agriculture is the one human system that should be able to substantially rely on photosynthesis: solar energy. It will be difficult if not impossible to address the issue of climate change without reforming the food system. This is a conclusion that has only recently been embraced by the environmental movement, which historically has disdained all agriculture as a lapse from wilderness and a source of pollution.1 But in the last few years, several of the major environmental groups have come to appreciate that a diversified, sustainable agriculture—which can sequester large amounts of carbon in the soil—holds the potential not just to mitigate but actually to help solve environmental problems, including climate change. Today, environmental organizations like the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Environmental Working Group are taking up the cause of food system reform, lending their expertise and clout to the movement.

But perhaps the food movement’s strongest claim on public attention today is the fact that the American diet of highly processed food laced with added fats and sugars is responsible for the epidemic of chronic diseases that threatens to bankrupt the health care system. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that fully three quarters of US health care spending goes to treat chronic diseases, most of which are preventable and linked to diet: heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and at least a third of all cancers. The health care crisis probably cannot be addressed without addressing the catastrophe of the American diet, and that diet is the direct (even if unintended) result of the way that our agriculture and food industries have been organized.

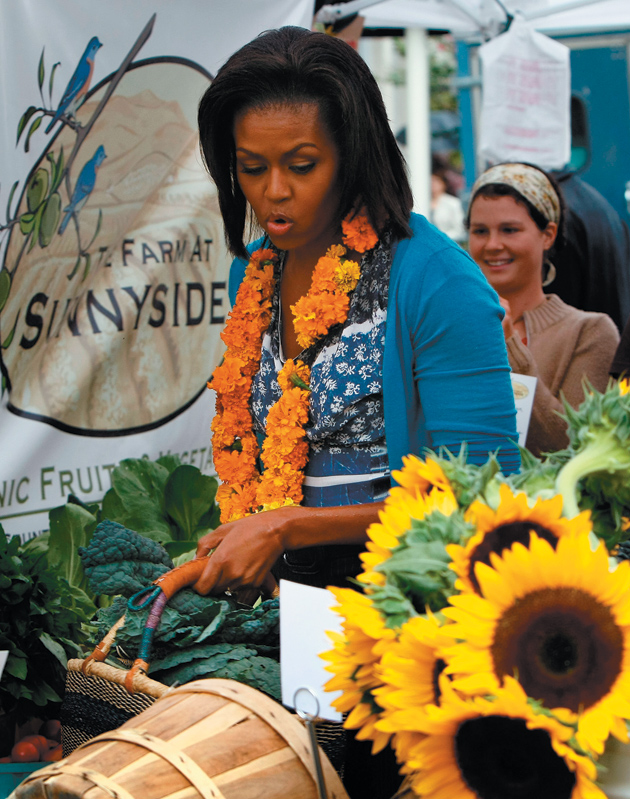

Michelle Obama’s recent foray into food politics, beginning with the organic garden she planted on the White House lawn last spring, suggests that the administration has made these connections. Her new “Let’s Move” campaign to combat childhood obesity might at first blush seem fairly anodyne, but in announcing the initiative in February, and in a surprisingly tough speech to the Grocery Manufacturers Association in March,2 the First Lady has effectively shifted the conversation about diet from the industry’s preferred ground of “personal responsibility” and exercise to a frank discussion of the way food is produced and marketed. “We need you not just to tweak around the edges,” she told the assembled food makers, “but to entirely rethink the products that you’re offering, the information that you provide about these products, and how you market those products to our children.”

Mrs. Obama explicitly rejected the conventional argument that the food industry is merely giving people the sugary, fatty, and salty foods they want, contending that the industry “doesn’t just respond to people’s natural inclinations—it also actually helps to shape them,” through the ways it creates products and markets them.

So far at least, Michelle Obama is the food movement’s most important ally in the administration, but there are signs of interest elsewhere. Under Commissioner Margaret Hamburg, the FDA has cracked down on deceptive food marketing and is said to be weighing a ban on the nontherapeutic use of antibiotics in factory farming. Attorney General Eric Holder recently avowed the Justice Department’s intention to pursue antitrust enforcement in agribusiness, one of the most highly concentrated sectors in the economy.3 At his side was Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, the former governor of Iowa, who has planted his own organic vegetable garden at the department and launched a new “Know Your Farmer, Know Your Food” initiative aimed at promoting local food systems as a way to both rebuild rural economies and improve access to healthy food.

Though Vilsack has so far left mostly undisturbed his department’s traditional deference to industrial agriculture, the new tone in Washington and the appointment of a handful of respected reformers (such as Tufts professor Kathleen Merrigan as deputy secretary of agriculture) has elicited a somewhat defensive, if not panicky, reaction from agribusiness. The Farm Bureau recently urged its members to go on the offensive against “food activists,” and a trade association representing pesticide makers called CropLife America wrote to Michelle Obama suggesting that her organic garden had unfairly maligned chemical agriculture and encouraging her to use “crop protection technologies”—i.e., pesticides.

The First Lady’s response is not known; however, the President subsequently rewarded CropLife by appointing one of its executives to a high-level trade post. This and other industry-friendly appointments suggest that while the administration may be sympathetic to elements of the food movement’s agenda, it isn’t about to take on agribusiness, at least not directly, at least until it senses at its back a much larger constituency for reform.

One way to interpret Michelle Obama’s deepening involvement in food issues is as an effort to build such a constituency, and in this she may well succeed. It’s a mistake to underestimate what a determined First Lady can accomplish. Lady Bird Johnson’s “highway beautification” campaign also seemed benign, but in the end it helped raise public consciousness about “the environment” (as it would soon come to be known) and put an end to the public’s tolerance for littering. And while Michelle Obama has explicitly limited her efforts to exhortation (“we can’t solve this problem by passing a bunch of laws in Washington,” she told the Grocery Manufacturers, no doubt much to their relief), her work is already creating a climate in which just such a “bunch of laws” might flourish: a handful of state legislatures, including California’s, are seriously considering levying new taxes on sugar in soft drinks, proposals considered hopelessly extreme less than a year ago.

The political ground is shifting, and the passage of health care reform may accelerate that movement. The bill itself contains a few provisions long promoted by the food movement (like calorie labeling on fast food menus), but more important could be the new political tendencies it sets in motion. If health insurers can no longer keep people with chronic diseases out of their patient pools, it stands to reason that the companies will develop a keener interest in preventing those diseases. They will then discover that they have a large stake in things like soda taxes and in precisely which kinds of calories the farm bill is subsidizing. As the insurance industry and the government take on more responsibility for the cost of treating expensive and largely preventable problems like obesity and type 2 diabetes, pressure for reform of the food system, and the American diet, can be expected to increase.

3.

It would be a mistake to conclude that the food movement’s agenda can be reduced to a set of laws, policies, and regulations, important as these may be. What is attracting so many people to the movement today (and young people in particular) is a much less conventional kind of politics, one that is about something more than food. The food movement is also about community, identity, pleasure, and, most notably, about carving out a new social and economic space removed from the influence of big corporations on the one side and government on the other. As the Diggers used to say during their San Francisco be-ins during the 1960s, food can serve as “an edible dynamic”—a means to a political end that is only nominally about food itself.

One can get a taste of this social space simply by hanging around a farmers’ market, an activity that a great many people enjoy today regardless of whether they’re in the market for a bunch of carrots or a head of lettuce. Farmers’ markets are thriving, more than five thousand strong, and there is a lot more going on in them than the exchange of money for food. Someone is collecting signatures on a petition. Someone else is playing music. Children are everywhere, sampling fresh produce, talking to farmers. Friends and acquaintances stop to chat. One sociologist calculated that people have ten times as many conversations at the farmers’ market than they do in the supermarket. Socially as well as sensually, the farmers’ market offers a remarkably rich and appealing environment. Someone buying food here may be acting not just as a consumer but also as a neighbor, a citizen, a parent, a cook. In many cities and towns, farmers’ markets have taken on (and not for the first time) the function of a lively new public square.

Though seldom articulated as such, the attempt to redefine, or escape, the traditional role of consumer has become an important aspiration of the food movement. In various ways it seeks to put the relationship between consumers and producers on a new, more neighborly footing, enriching the kinds of information exchanged in the transaction, and encouraging us to regard our food dollars as “votes” for a different kind of agriculture and, by implication, economy. The modern marketplace would have us decide what to buy strictly on the basis of price and self-interest; the food movement implicitly proposes that we enlarge our understanding of both those terms, suggesting that not just “good value” but ethical and political values should inform our buying decisions, and that we’ll get more satisfaction from our eating when they do.

That satisfaction helps to explain why many in the movement don’t greet the spectacle of large corporations adopting its goals, as some of them have begun to do, with unalloyed enthusiasm. Already Wal-Mart sells organic and local food, but this doesn’t greatly warm the hearts of food movement activists. One important impetus for the movement, or at least its locavore wing—those who are committed to eating as much locally produced food as possible—is the desire to get “beyond the barcode”—to create new economic and social structures outside of the mainstream consumer economy. Though not always articulated in these terms, the local food movement wants to decentralize the global economy, if not secede from it altogether, which is why in some communities, such as Great Barrington, Massachusetts, local currencies (the “BerkShare”) have popped up.

In fact it’s hard to say which comes first: the desire to promote local agriculture or the desire to promote local economies more generally by cutting ties, to whatever degree possible, to the national economic grid.4 This is at bottom a communitarian impulse, and it is one that is drawing support from the right as well as the left. Though the food movement has deep roots in the counterculture of the 1960s, its critique of corporate food and federal farm subsidies, as well as its emphasis on building community around food, has won it friends on the right. In his 2006 book Crunchy Cons, Rod Dreher identifies a strain of libertarian conservatism, often evangelical, that regards fast food as anathema to family values, and has seized on local food as a kind of culinary counterpart to home schooling.

It makes sense that food and farming should become a locus of attention for Americans disenchanted with consumer capitalism. Food is the place in daily life where corporatization can be most vividly felt: think about the homogenization of taste and experience represented by fast food. By the same token, food offers us one of the shortest, most appealing paths out of the corporate labyrinth, and into the sheer diversity of local flavors, varieties, and characters on offer at the farmers’ market.

Put another way, the food movement has set out to foster new forms of civil society. But instead of proposing that space as a counterweight to an overbearing state, as is usually the case, the food movement poses it against the dominance of corporations and their tendency to insinuate themselves into any aspect of our lives from which they can profit. As Wendell Berry writes, the corporations

will grow, deliver, and cook your food for you and (just like your mother) beg you to eat it. That they do not yet offer to insert it, prechewed, into your mouth is only because they have found no profitable way to do so.

The corporatization of something as basic and intimate as eating is, for many of us today, a good place to draw the line.

The Italian-born organization Slow Food, founded in 1986 as a protest against the arrival of McDonald’s in Rome, represents perhaps the purest expression of these politics. The organization, which now has 100,000 members in 132 countries, began by dedicating itself to “a firm defense of quiet material pleasure” but has lately waded into deeper political and economic waters. Slow Food’s founder and president, Carlo Petrini, a former leftist journalist, has much to say about how people’s daily food choices can rehabilitate the act of consumption, making it something more creative and progressive. In his new book Terra Madre: Forging a New Global Network of Sustainable Food Communities, Petrini urges eaters and food producers to join together in “food communities” outside of the usual distribution channels, which typically communicate little information beyond price and often exploit food producers. A farmers’ market is one manifestation of such a community, but Petrini is no mere locavore. Rather, he would have us practice on a global scale something like “local” economics, with its stress on neighborliness, as when, to cite one of his examples, eaters in the affluent West support nomad fisher folk in Mauritania by creating a market for their bottarga, or dried mullet roe. In helping to keep alive such a food tradition and way of life, the eater becomes something more than a consumer; she becomes what Petrini likes to call a “coproducer.”

Ever the Italian, Petrini puts pleasure at the center of his politics, which might explain why Slow Food is not always taken as seriously as it deserves to be. For why shouldn’t pleasure figure in the politics of the food movement? Good food is potentially one of the most democratic pleasures a society can offer, and is one of those subjects, like sports, that people can talk about across lines of class, ethnicity, and race.

The fact that the most humane and most environmentally sustainable choices frequently turn out to be the most delicious choices (as chefs such as Alice Waters and Dan Barber have pointed out) is fortuitous to say the least; it is also a welcome challenge to the more dismal choices typically posed by environmentalism, which most of the time is asking us to give up things we like. As Alice Waters has often said, it was not politics or ecology that brought her to organic agriculture, but rather the desire to recover a certain taste—one she had experienced as an exchange student in France. Of course democratizing such tastes, which under current policies tend to be more expensive, is the hard part, and must eventually lead the movement back to more conventional politics lest it be tagged as elitist.

But the movement’s interest in such seemingly mundane matters as taste and the other textures of everyday life is also one of its great strengths. Part of the movement’s critique of industrial food is that, with the rise of fast food and the collapse of everyday cooking, it has damaged family life and community by undermining the institution of the shared meal. Sad as it may be to bowl alone, eating alone can be sadder still, not least because it is eroding the civility on which our political culture depends.

That is the argument made by Janet Flammang, a political scientist, in a provocative new book called The Taste for Civilization: Food, Politics, and Civil Society. “Significant social and political costs have resulted from fast food and convenience foods,” she writes, “grazing and snacking instead of sitting down for leisurely meals, watching television during mealtimes instead of conversing”—40 percent of Americans watch television during meals—“viewing food as fuel rather than sustenance, discarding family recipes and foodways, and denying that eating has social and political dimensions.” The cultural contradictions of capitalism—its tendency to undermine the stabilizing social forms it depends on—are on vivid display at the modern American dinner table.

In a challenge to second-wave feminists who urged women to get out of the kitchen, Flammang suggests that by denigrating “foodwork”—everything involved in putting meals on the family table—we have unthinkingly wrecked one of the nurseries of democracy: the family meal. It is at “the temporary democracy of the table” that children learn the art of conversation and acquire the habits of civility—sharing, listening, taking turns, navigating differences, arguing without offending—and it is these habits that are lost when we eat alone and on the run. “Civility is not needed when one is by oneself.”5

These arguments resonated during the Senate debate over health care reform, when The New York Times reported that the private Senate dining room, where senators of both parties used to break bread together, stood empty. Flammang attributes some of the loss of civility in Washington to the aftermatch of the 1994 Republican Revolution, when Newt Gingrich, the new Speaker of the House, urged his freshman legislators not to move their families to Washington. Members now returned to their districts every weekend, sacrificing opportunities for socializing across party lines and, in the process, the “reservoirs of good will replenished at dinner parties.” It is much harder to vilify someone with whom you have shared a meal.

Flammang makes a convincing case for the centrality of food work and shared meals, much along the lines laid down by Carlo Petrini and Alice Waters, but with more historical perspective and theoretical rigor. A scholar of the women’s movement, she suggests that “American women are having second thoughts” about having left the kitchen.6 However, the answer is not for them simply to return to it, at least not alone, but rather “for everyone—men, women, and children—to go back to the kitchen, as in preindustrial days, and for the workplace to lessen its time demands on people.” Flammang points out that the historical priority of the American labor movement has been to fight for money, while the European labor movement has fought for time, which she suggests may have been the wiser choice.

At the very least this is a debate worth having, and it begins by taking food issues much more seriously than we have taken them. Flammang suggests that the invisibility of these issues until recently owes to the identification of food work with women and the (related) fact that eating, by its very nature, falls on the wrong side of the mind–body dualism. “Food is apprehended through the senses of touch, smell and taste,” she points out,

which rank lower on the hierarchy of senses than sight and hearing, which are typically thought to give rise to knowledge. In most of philosophy, religion, and literature, food is associated with body, animal, female, and appetite—things civilized men have sought to overcome with reason and knowledge.

Much to our loss. But food is invisible no longer and, in light of the mounting costs we’ve incurred by ignoring it, it is likely to demand much more of our attention in the future, as eaters, parents, and citizens. It is only a matter of time before politicians seize on the power of the food issue, which besides being increasingly urgent is also almost primal, indeed is in some deep sense proto- political. For where do all politics begin if not in the high chair?—at that fateful moment when mother, or father, raises a spoonful of food to the lips of the baby who clamps shut her mouth, shakes her head no, and for the very first time in life awakens to and asserts her sovereign power.

This Issue

June 10, 2010

-

1

Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth made scant mention of food or agriculture, but in his recent follow-up book, Our Choice: A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis (2009), he devotes a long chapter to the subject of our food choices and their bearing on climate. ↩

-

2

Ms. Obama’s speech can be read at [www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-first-lady-a-grocery-manufacturers-association-conference](http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-first-lady-a-grocery-manufacturers-association-conference). ↩

-

3

Speaking in March at an Iowa “listening session” about agribusiness concentration, Holder said, “long periods of reckless deregulation have restricted competition” in agriculture. Indeed: four companies (JBS/Swift, Tyson, Cargill, and National Beef Packers) slaughter 85 percent of US beef cattle; two companies (Monsanto and DuPont) sell more than 50 percent of US corn seed; one company (Dean Foods) controls 40 percent of the US milk supply. ↩

-

4

For an interesting case study about a depressed Vermont mining town that turned to local food and agriculture to revitalize itself, see Ben Hewitt, The Town That Food Saved: How One Community Found Vitality in Local Food (Rodale, 2009). ↩

-

5

See David M. Herszenhorn, “In Senate Health Care Vote, New Partisan Vitriol,” The New York Times, December 23, 2009: “Senator Max Baucus, Democrat of Montana and chairman of the Finance Committee, said the political—and often personal—divisions that now characterize the Senate were epitomized by the empty tables in the senators’ private dining room, a place where members of both parties used to break bread. ‘Nobody goes there anymore,’ Mr. Baucus said. ‘When I was here 10, 15, 30 years ago, that the place you would go to talk to senators, let your hair down, just kind of compare notes, no spouses allowed, no staff, nobody. It is now empty.'” ↩

-

6

The stirrings of a new “radical homemakers” movement lends some support to the assertion. See Shannon Hayes’s Radical Homemakers: Reclaiming Domesticity from a Consumer Culture (Left to Write Press, 2010). ↩