1.

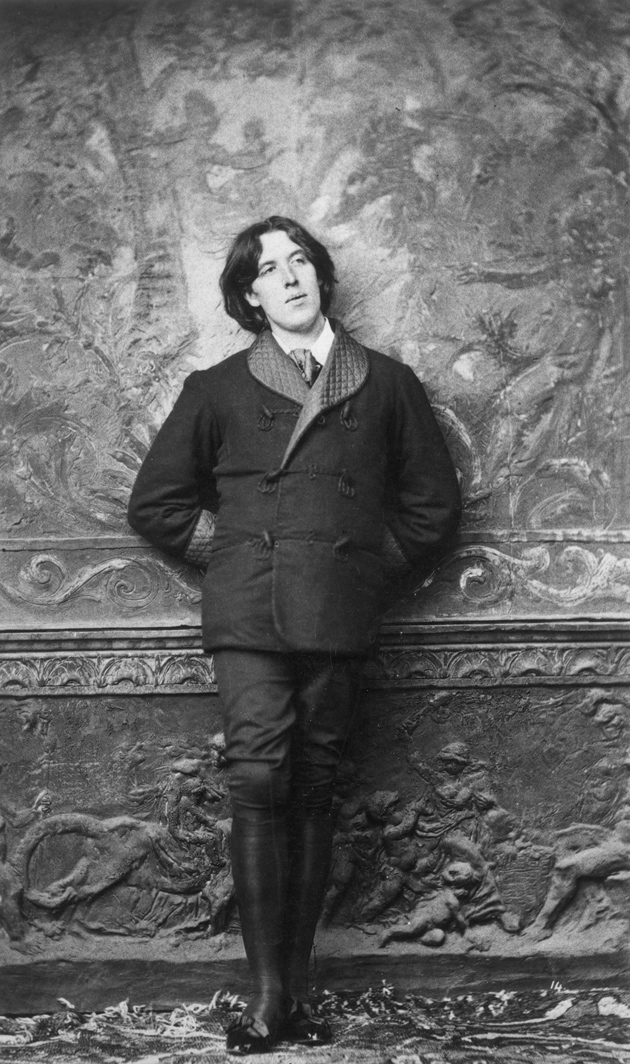

When asked what he intended to do after finishing at Oxford, the young Oscar Wilde—who was already well known not only for his outré persona (“I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china,” etc.), but for his brilliant achievements as a classics scholar—made it clear in which direction his ambitions lay. “God knows,” the twenty-three-year-old told his great friend David Hunter Blair, who had asked Wilde about his postgraduate plans, and who later fondly recalled the conversation in his 1939 memoir, In Victorian Days. “I won’t be a dried-up Oxford don, anyhow. I’ll be a poet, a writer, a dramatist. Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious.”

As we know, his prediction would be spectacularly fulfilled: like a character in one of the Greek tragedies he was able to translate so fluently as a student, his short life followed a spectacular trajectory from fame to infamy, from the heady triumphs of his post-Oxford days, when he was already famous enough to be lampooned by Gilbert and Sullivan in Patience, to the dreadful peripeteia of the trials and imprisonment. But to some of those who knew him at the time, Wilde’s emphatic rejection of the scholarly life must have come as something of a surprise.

He had, after all, shown a remarkable flair for the classics from the start. At the Portora Royal School, where he’d been sent in the autumn of 1864, just before his tenth birthday, he won the classical medal examination with his extempore translations from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon (the tragedy he loved above all others) and the Carpenter Prize for his superior performance on the examination on the Greek New Testament. Later, at Trinity College, Dublin, he took a first in his freshman classical exams and went on to win the Berkeley Gold Medal for his paper on a subject that was, perhaps, not without augury: the Fragmenta comicorum graecorum, “Fragments of the Greek Comics,” the great scholarly edition by the early-nineteenth-century German philologue Augustus Meineke. (According to his friend Robert Sherard, he occasionally pawned the medal when he needed money, but managed always to redeem it, keeping it until the end of his life.)

After transferring to Magdalen College, Oxford, in the autumn of 1874, Wilde scored highest marks on his entrance exams, and finished by taking a prestigious double first in “Greats,” the relatively recent, classics-based curriculum officially known as literae humaniores. Always attentive to his image, he liked to imply that these successes came easily—“He liked to pose as a dilettante trifling with his books,” Hunter Blair recalled—but in fact put in “hours of assiduous and laborious reading, often into the small hours of the morning.” Whatever his taste for lilies and Sèvres, he was a “grind.”

Wilde’s activities immediately following his departure from Oxford suggest, if anything, a certain unwillingness to abandon the domain of “dried-up old dons.” While scrounging for ways to keep himself employed, he wrote his old friend George Macmillan, of the publishing family, offering to take on projects that would have daunted full-blown classics scholars twice his age: a new translation of Herodotus, a new edition of Euripides’ Madness of Hercules and Phoenician Maidens. He applied, unsuccessfully, for an archaeology scholarship; he had a hand in an 1880 production of Agamemnon that was attended by Browning and Tennyson.

Because he did indeed end up traveling down the path he announced to David Hunter Blair, we can never know what the mature work produced by this “classical” Wilde might have been like—the Wilde who could easily have gone on to do a D.Phil. in classics, Wilde the don, Wilde the important and perhaps revolutionary late-nineteenth-century scholar of Greek literature and society. Of that Wilde, the extant record affords us only a few tantalizing glimpses: a university prize essay, an unsigned review article, journeyman’s pieces that nonetheless reveal a characteristic bravura. This partial view has occasionally been enlarged over the years by the publication of fascinating bits of juvenilia (“Hellenism,” a fragmentary set of notes about Spartan civilization, was published only in 1979). Now we have The Women of Homer, a substantial although unfinished paper on Homer’s female characters that reminds us once more how strongly Wilde’s classical training underpinned the sensibility that would make him so famous.

2.

Wilde’s copy of the Nichomachean Ethics, dated 1877, contains this suggestive gloss on the text: “Man makes his end for himself out of himself: no end is imposed by external considerations, he must realize his true nature, must be what nature orders, so must discover what his nature is.” At the time he was beginning his studies, the tradition of secondary and university instruction in the classics did not necessarily encourage a profound examination of what one’s “true nature” might be. A great premium was placed on proficiency in the languages: students were expected to be able to translate passages from the classical languages into English—and from English into Greek and Latin prose and verse. While still at Trinity, Wilde was asked on one exam to translate a fragment of a text about Odysseus into Elizabethan prose, and then was required to translate selections from Wordsworth, Shakespeare, and Matthew Arnold into Greek.1

Advertisement

Luckily, Wilde, whose linguistic abilities were certainly formidable—years later, a former Portora schoolmate recalled his ability to “grasp the nuances of the various phases of the Greek Middle Voice and of the vagaries of Greek conditional clauses”—was to fall into the hands of the right professors. His Trinity master was the Reverend J.P. Mahaffy, a distinguished classicist who had a special interest in later Greek antiquity, and who was, too, a celebrated wit—a quality that must have appealed to his young student. (Informed that the current tenant of an academic post he coveted was ill, Mahaffy replied, “Nothing trivial, I hope?”)

In an 1874 book called Social Life in Greece, Mahaffy argued for a vision of the Greeks and their civilization as something more than a mausoleum of culture, “mere treasure-houses of roots and forms to be sought out by comparative grammarians.” Among other things, he showed a refreshing willingness to dust off contemporary attitudes toward one Hellenic institution that would have had a special if secret resonance for Wilde: homosexuality. “There is no field of enquiry,” Mahaffy wrote in Social Life in Greece, “where we are so dogmatic in our social prejudices, and so determined by the special circumstances of our age and country.”

Mahaffy’s advocacy of a living engagement with the civilization of the Mediterranean—still somewhat of a novelty at the time—would land the young Wilde in trouble. In the spring of 1877 he accompanied his former professor on a trip to Italy and Greece; after returning to Oxford several weeks late in the term, Wilde was “rusticated”—forced to leave university for the duration of term. The irony of being temporarily expelled from his classics curriculum for having immersed himself in the Greek world was not lost on the future master of the epigram, who observed that he “was sent down from Oxford for being the first undergraduate to visit Olympia.”

The Oxford that punished the unrepentant Wilde had, in fact, been shaking off the old ways, transformed by the energetic reforms of Benjamin Jowett, Regius Professor of Greek, Master of Balliol, and translator of Plato. It was Jowett who insisted that Greats include important currents in contemporary thought (as a young man he had been devoted to Kant); who saw, indeed, the classics as a natural conduit for modern liberal thought. Instrumental in shifting the emphasis of the curriculum from Roman to Greek authors, he made Plato central to it; not coincidentally, the philosopher’s dialectical method was embodied in the intimate one-on-one tutorial system (which occasionally fomented Platonic passions of a less intellectual variety).2

The special Platonic emphasis at Oxford was clearly what animated Wilde’s later, admiring characterization of the curriculum as one in which

one can be, simultaneously, brilliant and unreasonable, speculative and well-informed, creative as well as critical, and write with all the passion of youth about the truths which belong to the august serenity of old age.

Here, perhaps, is the root of the characteristically Wildean taste for entwining ostensibly incompatible qualities. His work encompassed, sometimes uneasily, what he saw as his “Gothic” and “Greek” sides, veering between a grandiose Romanticism and an astringent Classicism, the fusty nineteenth-century melodrama of most of his theater and the crisp modernism of his critical thought.

Mahaffy and Jowett weren’t the only Hellenists advocating a profoundly engaged approach to the classics during the latter half of the nineteenth century. During Wilde’s time at Oxford the literary critic and poet John Addington Symonds was publishing his two-volume Studies of the Greek Poets (1873, 1876). While their earnestness and dogged effort at comprehensiveness may have been exhaustingly typical of mid-Victorian criticism, these volumes were particularly celebrated (or derided) for their unusually passionate, personal, and florid style: a style that hinted at a more than purely academic degree of investment in the subject, and suggested, once again, that the Greeks could have more than a “dry as dust” meaning for the present day. Symonds, like Mahaffy, urged his readers to visit the Mediterranean sites in order to be able to feel the still-living connection to ancient civilizations. In 1874 he published a three-volume collection of travel pieces, Sketches and Studies in Italy and Greece.

Advertisement

One secret reason for Symonds’s engagement is by now well known. Like certain others of the “Oxford Hellenists” of the mid-nineteenth century—including Walter Pater, another figure whose work Wilde would admire extravagantly—Symonds was a secret homosexual who sought, through readings of the Greek classics, to find both expression for and justification of his own sexual nature. Indeed, Symonds later wrote in his memoirs that he had virtually discovered his sexuality through a reading of Plato’s Phaedrus and Symposium: the night he read their “panegyric of paiderastic love” was “one of the most important of my life.” In time, he would go on to write explicitly about Greek homosexuality in A Problem in Greek Ethics, a text that was circulated privately for ten years before its eventual publication, in 1883, and is now seen as a foundational document of modern homosexual studies.

However flowery his style and whatever lip service he paid to conventional condemnation of “paiderastia,” there were those who were able to read between the lines of Symonds’s work—especially the lines of the final chapter of the second volume of Studies of the Greek Poets, with its controversial defense of Greek rather than Judeo-Christian morals, which he dismissed as “theistic fancies liable to change.” (Phyllis Grosskurth’s 1964 biography of Symonds retells an amusing anecdote about a “shocked compositor” who, after setting the type of Symonds’s book, wrote an outraged letter to the author.) The critic and sometime watercolorist Richard St John Tyrwhitt fulminated against Symonds’s book in a lengthy article that appeared in The Contemporary Review, warning that Studies of the Greek Poets advocated “the total denial of any moral restraint on any human impulses.” As a result of the controversy surrounding the second volume of his study, Symonds reluctantly withdrew his candidacy for the Poetry Chair at Oxford.

Small wonder that Wilde’s friend Frank Harris later recalled that Symonds’s Studies of the Greek Poets was “perpetually” to be seen in Wilde’s hands. And all the more interesting, too, that when during the summer holiday of 1876 the ambitious undergraduate turned his hand to reviewing Symonds’s latest volume—the text now published as The Women of Homer—the chapter to which he directed his critical attention was not the scandalous final one, with its implicit defense of male homosexuality. Instead, Wilde wrote about a chapter in which Symonds treated a subject that was all too clearly a delicate one for the author, an unhappily married homosexual, as well as to his eager young reader, another secret homosexual who would marry one day: women.

3.

The Women of Homer now takes its place as the earliest of several youthful classical writings that amply display a precocious intellectual and critical aplomb. A disjointed mass of notes and paragraphs that Wilde produced in about 1877 was edited a century later into a misleadingly finished-looking “essay” called “Hellenism.” However unoriginal this account of Spartan culture often is, it sometimes betrays a shrewd and crisply unsentimental appreciation of the Greeks and their qualities—such shrewdness and lack of sentimentality being the very qualities that mark the “Greek” facets of Wilde’s own work. Not the least interesting of its assertions is that the Greek city-states’ “selfish feeling of exclusive patriotism, this worship of the πόλις [polis, city-state] as opposed to the πάτρια [patria, homeland]”—the quality with which the nineteenth-century admirers of Rome typically reproached the squabbling Greeks—was, in fact, the key to the Greek cultural achievement. It was this “selfishness” that, as Wilde saw it, saved the Greeks “from the mediocre sameness of thought and feeling which seems always to exist in the cities of great empires.”

In an 1879 essay called “Historical Criticism in Antiquity,” composed for the Chancellor’s Essay Prize, Wilde strikingly rejected the prevailing Victorian appreciation of the classical texts as exemplars of “serenity and balance,”3 advocating instead what today we would call the decadent strain in Greek culture—what he celebrated as “that refined effeminacy, that overstrained gracefulness of attitude” to be found in the later poets and sculptors. Mahaffy’s insistence on the living relevance of the Greeks bore fruit in this essay: Wilde goes on to observe, provocatively but shrewdly, that the late nineteenth century, like the late fifth and the fourth centuries BC, was an age of “style” (in implicit opposition to the lofty “substance” of an earlier era).

To the severity and gravitas of the high classical tradition, of which Sophocles has always been the supreme representative in dramatic literature, Wilde prefers Euripides, as he does the Hellenistic sculptors and other poets and artists who “prefer music to meaning and melody to reality.” Here we detect the first stirrings of an argument about aesthetics and society, the provocative elevation of “style” over “substance,” that would find its final form in mature works such as “The Decay of Lying,” “The Truth of Masks,” and Wilde’s critical writings.

At virtually the same moment that he composed the Chancellor’s Essay, Wilde contributed to the Athenaeum a long, unsigned review of Sir Richard Jebb’s entries on Greek history and literature in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The twenty-five-year-old blithely took the professor of Greek at Glasgow to task for either denigrating, or omitting altogether from his article, authors or texts that were unconcerned with “serenity and balance.” Among the former was the notoriously effeminate tragedian Agathon, whom Wilde celebrates as “the aesthetic poet of the Periclean age.” Among the latter was a bizarre Hellenistic poem called Pharmaceutria, an idyll about a love- maddened witch that, Wilde asserts, “for fiery colour and splendid concentration of passion is only equalled by the ‘Attis’ of Catullus.” The admiring reference to the Roman poem—a lengthy work about a handsome acolyte of the goddess Cybele who castrates himself in a transport of religious fervor—is itself worthy of note. Barely out of university, the young Wilde’s taste for extreme gestures, in literature as in life, was plain.

The authority and highly defined taste, the willingness to attack established scholars and to propose startlingly original interpretations, that distinguish “Hellenism,” the Chancellor’s Essay, and the Britannica article of 1879 are evident in The Women of Homer, which Wilde began when he was not quite twenty-two. It is remarkable, not least, for standing in refreshing contrast to the platitudinous moonings of Symonds himself, who is unable to see the preeminent female characters in Homer—Helen, Penelope, and the maiden Nausicaa—as anything but cartoon figures representing conventional types of femininity.

As a product of the “Aesthetic” era, Symonds is good on certain features of Helen. (He gets just right the curious and striking way in which Homer’s Helen “is not touched by the passion she inspires, or by the wreck of empires ruined in her cause.”) But while he is capable of appreciating the Iliad’s Helen as the abstract symbol of beauty’s sheer force in the world—his evident preoccupation—he has no feel whatever for the subtler Helen of the Odyssey, of whom he states, with disastrous obtuseness, that “the character of Helen loses much of its charm and becomes more conventional.”

Here Symonds is referring to Helen’s appearance in Book 4, in which Odysseus’ young son, Telemachus, comes calling on Helen’s husband, the Spartan king Menelaus, in order to obtain news of his long-lost father. It would, in fact, be hard to find a more unforgettable and less conventional scene in all of Homer. As Helen and Menelaus regale the awestruck youngster with tales of the war, ostensibly to share memories of Odysseus with the son who never knew him, their exchange suggests, with brilliant subtlety, that this marriage is still riven with tensions long after the wayward Helen has returned home with her husband. Symonds ignores all of this—and, bizarrely, makes nothing of the fact that Helen has drugged her guests’ wine with a kind of tranquilizer before the storytelling begins: not at all what you’d call “conventional.”

His reading of Penelope, the long-suffering heroine of the Odyssey, is similarly trivializing. For him, the “central point” of Odysseus’ wife is “intense love of her home, an almost cat-like attachment to the house.” In her famously clever ruse—the nightly unraveling of the shroud she claims to be weaving for her father-in-law—he sees not an impressive canniness but only a pat “parable” about those “who in their weakness do and undo daily what they would fain never do at all.” For him, Penelope is “far less fascinating than Helen.”

Symonds waxes ecstatic only about Nausicaa, the virginal princess who so memorably, and with such aplomb, rescues the shipwrecked Odysseus when he washes up on her island home—“the most perfect maiden, the purest, freshest, lightest-hearted girl of Greek romance.” In this appreciation, as in so many of his interpretations of Homer’s women, Symonds seems trapped by a mid-Victorian fantasy that says more about his own anxieties about women—about his desire, perhaps, to encase them in manageable caricatures—than it does about the literary characters in question.

Wilde’s reaction to Symonds’s text reveals the same astringent rigor that characterizes his attack on Jebb. He begins with an impatient scholarly complaint, criticizing Symonds’s failure to include all the relevant texts in his discussion of Helen (not least, the speech by the classical sophist Isocrates known as the “Encomium of Helen”). What makes Wilde’s essay really fascinating, though, are the flashes of his own distinctively sharp and original interpretative acumen.

In his discussion of Helen, Symonds had argued that a lost trilogy about her by Sophocles would have presented her as “a woman whose character deserved the most profound analysis”—an assumption wholly in keeping with the contemporary assessment of that playwright as the master of character. To this Wilde retorts, startlingly but with some justice, that “profound analysis” is not necessarily to be expected of the great Athenian dramatist in the case of Antigone: “I hardly think that the drawing of Antigone in the play of that name justifies the expression ‘profound analysis.'” And he is right: the Theban princess, while a powerful figure, is not a subtle one. The Women of Homer offers a number of such bracing zingers.

By far the most arresting observation that Wilde makes in his response to Symonds’s catalog of Homeric women is one concerning Penelope, the character about whom Symonds shows himself to be the least perceptive. Wilde remarks on what he calls an “extremely subtle psychological point” that Homer makes about her personality, one that “shows that Homer had accurately studied the nature of women.” Rather than being the placid homebody that Symonds insists she is, Penelope, Wilde understands, is in fact strangely liberated by her famous dilemma: the interminable courtship of her by the suitors during Odysseus’ absence awakens and sharpens in her the very qualities that make her an ideal mate for her husband. (Symonds simply finds her acts of cunning irritating: “provocative of anger.”) Those twenty years without Odysseus may have been lonely, but by the same token they place Penelope squarely at center stage. “Though his return was the consummation,” Wilde writes, with a psychological insight that would be remarkable in someone much older and more experienced than an undergraduate in his early twenties, “yet it was in some way the breaking up of her life; for her occupation was gone.”

Homer, if not Symonds, clearly recognizes this, giving Penelope a number of scenes that show that she is in many ways ambivalent about the suitors—whose attentions, the poet hints, she unconsciously enjoys. In Book 19, for instance, Odysseus’ queen famously takes the mysterious beggar—actually Odysseus in disguise—into her confidence, telling him about a dream she has had in which a mountain eagle attacks twenty tame geese she has lovingly kept: there is no question that the geese are meant to represent the suitors, and the eagle, Odysseus.

Wilde bewails the failure of Symonds and so many other contemporary critics to recognize this conflicted aspect of Penelope’s character:

It is entirely misunderstood, however, by Mr Symonds and, indeed, by all other writers I have read. It shows us how great was her longing, how terrible the anguish of her soul, and it makes her final recognition of [Odysseus] doubly impressive.

The private desire behind the public repudiation, the anguished dissolution triggered by a long-awaited “consummation”: Wilde’s ability to discern, beneath the attitudes imposed on women by society, the sharp and surprising contours of unexpected emotions is what would make The Importance of Being Earnest the most original and most artistically successful of his works.

“Entirely misunderstood…by all other writers I have read.” The breathtaking self-assurance of this pronouncement suggests why Wilde’s long-forgotten text is intriguing, for reasons other than the glimpse it gives us of the road not taken by a significant cultural figure. The confrontation between Wilde and Symonds is, in the end, a confrontation between two eras. In Wilde’s dismissal of Symonds and the rest, you can already hear not only the voice of the mature writer, blithely dismissing the intellectual and social conventions of his age, but the voice of an as yet unborn criticism, one particularly willing to question prevailing assumptions about style, canons, and gender. Like the best of his mature work, this juvenile piece seems to leapfrog forward from the late-nineteenth to the late-twentieth century.

4.

Not the least of the twentieth-century phenomena that Wilde so uncannily anticipated was the cult of celebrity; and indeed, soon after deciding against a career as a classicist, he was making his first serious effort at courting international fame. During his 1882 tour of America, he was already showing a shrewd understanding of the uses to which that most Greek of literary forms, the epigram, might be put in the age of the telegram and the newspaper. (“His sayings are telegraphed all over the world,” the Pall Mall Gazette bemusedly reported of Wilde’s American visit.) If he invoked the Greeks at all in his American interviews it was to compliment a local poet:

Whitman is a great writer…. There is more of the Greek residing in him than in any modern poet. His poetry is Homeric in its large pure delight of men and woman, and in the joy the writer has and shows through it all in the sunshine and breeze of outdoor life.4

But as we know, it was in Wilde himself more than anyone that the Greek spirit resided. If no one today seriously wishes that Wilde had become an Oxford classics don, it’s at least in part because his own “Greekness”—the deep understanding of the rhetorical uses of style, the taste for piquant syllogism, the ever-evolving aversion to sentimentality (which reached its apogee in Earnest), and, in the end, the tragic understanding of the meaning of suffering—made itself felt so strongly in the work he produced as a poet, writer, and dramatist.

There is, however, one unwritten text that we might legitimately covet. Reading The Women of Homer, it’s almost impossible not to wish that we might instead possess a review of the chapter in Studies of the Greek Poets that was likely to have had greater personal meaning for him than did Symonds’s musings on Homer’s women. I refer of course to the scandalous final chapter, with Symonds’s coded defense of illicit desire and rejection of conventional morality—the very subjects and positions that Wilde himself would take up so sensationally, to his credit and to his cost. But then, you could say that the whole of Oscar Wilde’s life and work soon after he laid aside the unfinished essay—everything he did after abandoning Oxford for London, philology for fame—was a commentary on that unmentioned and unmentionable chapter of Symonds.

This Issue

November 11, 2010

-

1

This and other tidbits about the writer’s intellectual formation are retailed in Thomas Wright’s admiring intellectual biography of Wilde, Built of Books: How Reading Defined the Life of Oscar Wilde, a highly useful survey of what Wilde was reading at every stage of his life, to which my discussion of Wilde’s schooling is indebted. ↩

-

2

See Linda Dowling’s intriguing study Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford (Cornell University Press, 1994). ↩

-

3

So E.R. Dodds, characterizing the “orthodox Victorian assumption,” cited in Richard Ellmann’s Oscar Wilde: A Life (Knopf, 1984), p. 108. ↩

-

4

A generous and welcome sampling of Wilde’s American interviews can now be found in Oscar Wilde in America: The Interviews, edited by Matthew Hofer and Gary Scharnhorst (University of Illinois Press, 2010). ↩