“Hell no?” asked Rush Limbaugh in his August 14 broadcast. “Damn no! We’re the party of Damn no! We’re the party of Hell no! We’re the party that’s going to save the United States of America!”

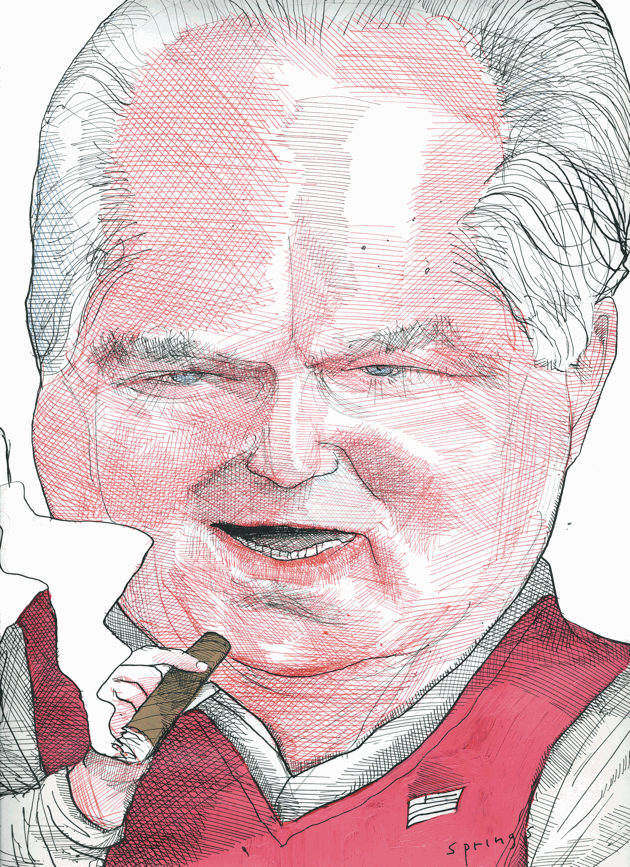

Limbaugh was revising the congressional minority leader John Boehner’s “Hell No!” rejection speech against national health care reform. Naturally he took Boehner’s slang a step further into cussing. A sign of solidarity, you might say, but also a stroke of one-upmanship, and in both respects a characteristic message from the virtual leader and most admired celebrity of the Republican Party; his talk show reaches between 14 and 30 million listeners, more than any other radio broadcast.

Superficial observers for two decades have treated Limbaugh as a cutup, a frat boy, a brawler with a barroom gift for getting people to listen. The facts are otherwise and have never been hidden. Rush Limbaugh III is a member of a highly respected family of Cape Girardeau, a small town in the border state of Missouri. He comes from a line of distinguished lawyers, including his brother David and two judges in the last two generations: Stephen Limbaugh Sr., a federal judge in St. Louis, and Stephen Limbaugh Jr. (the cousin of Rush), who in 2008 was sworn in as his father retired from the same US district court. A military link on the Limbaugh family website goes further back. It names at least six ancestors who served in the Civil War, all of them on the Confederate side. These data are a reminder that the supposed division between the “chattering class” and ordinary Americans may be a mask for a phenomenon both larger and more specific: the southernization of American politics. It shows more plainly now than at any moment since Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign.

Limbaugh seldom speaks overtly about race. Disgust with the federal government is his preferred device for letting the subject in: the Nanny State, the Mammy State, Obamacare, Yo Mamma Care. Limbaugh, who coined the third of these phrases, has not had to say the second and fourth to keep them playing around the listener’s ear. In the background too, in any given hour, he is working up a grotesque idea of the “Democrat Party.” The party as he presents it is composed of superannuated aristocrats, pretentious arrivistes, and a ragtag swarm of dependents; the model here is the nineteenth-century imagery of carpetbaggers and their lately freed camp followers. The Rebel germ in Limbaugh was never appeased by healing afterthoughts about the Union government that came south and overstayed its welcome. In a throwaway riff last summer, for no good reason except irritation, he deplored an hour he was forced to spend listening to federal officials celebrate the subsidy, design, and construction of a new federal courthouse in Cape Girardeau, the Limbaugh Building, named after his grandfather, Rush Limbaugh Sr. It might seem an honor but it was a government project all the same.

His mischief can be more acrid. Over the bass guitar blues that opens his show, on September 7 Limbaugh could be heard singing a softer song. What was this? Well, President Obama at a Labor Day rally had performed a riff of his own. “Some powerful interests who had been dominating the agenda in Washington for a very long time,” Obama said, are “not always happy with me. They talk about me like a dog.” The peculiar lapse and the provocation it offered were not lost on Limbaugh; with malicious cheer he trotted out the lyrics sung in 1952 by Patti Page: “How much is that doggie in the window?” A mindless improvisation, yet it touched a nerve—exposing to the glare of public notice Obama’s synthetic folksiness (often signaled by excessive reliance on the word “folks”).

Obama had transgressed an invisible boundary in that Labor Day speech, and the hunter Limbaugh was bound to go after him. The president who talked of being treated like a dog had lately returned from a week in Martha’s Vineyard. Before that, as Limbaugh recalled, we saw Michelle Obama’s vacation in Spain with half a dozen friends and the mandatory entourage of sixty Secret Service agents. Between the two junkets came a fast visit to the oil-spill coast of Louisiana, “the Redneck Riviera.” It was about this time that he started calling her Michelle Antoinette Obama.

Granted, Limbaugh went after Bill Clinton as relentlessly. Still, no careful listener can doubt that race is an element in the new tone of presumptive insolence. It is also true that the Obama administration—foolishly, if they weren’t prepared for a fight—called out Limbaugh by name early on. “You can’t just listen to Rush Limbaugh and get things done,” Obama told the Republican congressional leadership a few days after taking office when he floated his dream of a bipartisan majority to pass large reforms. The confident dismissal of a dangerous enemy came at a time of unexamined faith in himself. It now seems plain that between February and April 2009, Obama believed that his election had disclosed not a beginning but the completion of a change in American manners. Everything Limbaugh has done in the past two years depended on a different reading of that triumph and a hunch about the weakness of character and experience that underlay it.

Advertisement

When, in one of his first acts as president, Obama announced the closing of Guantánamo and seemed to be passively waiting for a plan to emerge, Limbaugh saw an opening. He lives to destroy and to have a good time. His favorite target is the beautiful intention that has nothing underneath it—no plan, no powerful backers, no swell of popular support. How many such liberal ideas did Obama vaguely share with the American people in the first six months of his presidency? When the health care negotiations dragged into summer 2009, Limbaugh turned the President’s left flank and executed the first of the maneuvers that may end by gaining a Republican majority in 2010. The occasion was the President’s comment, at the end of a press conference ostensibly devoted to health care, on the arrest of Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Obama said nobody could doubt that the Cambridge police had “acted stupidly.”

A sympathetic viewer might have worried then: How many portfolios does he think he holds? Limbaugh went much further. He blew up the questionable line and made it a seven-day story. Why does Obama want to get in on the action everywhere? This man is in every corner and every moment of your lives, and if you think it’s bad already (a growl, a shuffle of papers), just wait till Obamacare is passed. He’ll be telling you which doctor to go to. He’ll be telling you what to eat. He’ll be telling you to exercise and exactly how much each day. He thinks he knows more about crime in the streets than a cop on the beat.

Like all demagogues, Limbaugh knows the value of repetition. His work in the spring and summer of 2009 was to teach the Republican Party to repeat the word “No.” They must execute an across-the-board refusal and nullification of Obama’s initiatives. He wanted the President to fail, and said so. Admonished that such a sentiment was unpatriotic, he backed and filled and said, no, it wasn’t that he wanted the country to suffer. Obama had to fail if the country was going to succeed. Limbaugh does not apologize and he doesn’t explain, and his incitements have left a deeper mark than they did in 1995 when he blamed the government for the terrorist bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

Since he struck that defiant pose, Limbaugh’s reputation has risen higher again than might have seemed possible. He created and is still the leading practitioner of the talk-radio culture that instructs the Tea Party. According to an October 14 story by Kate Zernike in The New York Times, there are 138 Tea Party candidates running for office in the House and Senate this year. If as many as thirty of them win, they will make a substantial force in national politics, and all are obedient to an easily iterated string of maxims: drastic reduction of federal taxes; mandatory cuts in government spending; increased funding for the armed forces. Unlike Newt Gingrich, who led the Republican victory of 1994, Limbaugh does not have to pass legislation or run for reelection and he is not answerable to an ethics committee. His estimated worth—largely from his salary and bonuses—is around a billion dollars, and his sponsors are not about to give him up.

The far-right Republicans and unhappy independents who are led by talk radio are generally known as “angry.” Limbaugh makes them angrier even as he offers a story to focus their rage and resentment. Rage about what? The loss of “the America we grew up in.” Of course, only people over sixty grew up in a country much less chaotic than American society today; but the myth of the Fifties has been going strong since the Seventies, in TV shows like Happy Days and movies like Back to the Future. The Fifties, when America stood its ground in the cold war, are linked in this imagining to the Eighties, when Ronald Reagan won the cold war. The myth of Reagan as a transcendent embodiment of uniquely American virtues has outlived the facts of his presidency.

Yet Limbaugh, unlike Glenn Beck and Sean Hannity, does very little trafficking in myth. His ground note is the booming old-school pledge-of-allegiance voice, reminiscent of Paul Harvey and George Putnam, but that starting point is a misleading clue to his temperament and procedure. Where Beck reads and quotes from the Drudge Report and crank secondary literature, Limbaugh always has spread before him the latest from Reuters, AP, Politico, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and a good many other direct sources. He treats them with a reassuring bustle, as of a man about serious business: “Lots to do!” Behind the compulsion is a complex nature—boisterous, insinuating, self-righteous, almost infantile in his self-love. Lots to do! What Limbaugh’s appreciators see in him and dote on is a quality both greedy and innocent.

Advertisement

Limbaugh and Beck are tastes as opposite as John Philip Sousa and Burt Bacharach. Limbaugh cannot bear to share the stage with anyone. Beck, on radio, is hard to imagine without the two sidekicks who giggle and do the trash talk and sometimes pull him into line. (On television, on the other hand, he performs solo with a blackboard, and draws diagrams of history, sociology, anthropology, and political theory to prove the imminence of the totalitarian threat within America today.) When Beck is not on his knees (“Pray for me. Pray for our country”), he is standing on tiptoe reciting a history lesson. The high jinks and clowning that normally lead off the radio show would not be out of place in a college dorm; and as in that milieu and format, a female voice of any kind would feel out of place. Beck’s voice in his religious interludes shifts from the usual silken tenor to something weak and trembly. The common trait in all his poses and voices is excess of drama. There are too many veerings to keep track of, and an awkward kind of sympathy draws you in.

“What you are about to hear,” says a grave announcer at the start of each half-hour of Beck’s radio show, “is the fusion of entertainment and enlightenment.” There follows a mash-up of disturbing splinters of speeches and music—Ronald Reagan saying that America is “the last stand on earth” and another voice saying “We will be heard.” The last sentence is an echo of William Lloyd Garrison’s opening issue of The Liberator: “I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—and I will be heard.” The echo is probably conscious, for Beck’s version of extreme libertarianism relies at every point on the antithesis of freedom and slavery, and he pictures himself as a liberator of the slaves of our time: modest men and women, the freeholders and small holders of the old republican pamphlet literature, whose private property is being absorbed into the sprawling eminent domain of a new “collectivism” spearheaded by Barack Obama.

The Tea Party rally on August 28 at the Lincoln Memorial, largely organized by Beck, coincided freakishly with the date of Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington of forty-seven years before. Beck seems not to have realized as much when he set the schedule, but he came to regard the coincidence as a mark of divine favor. “This is an awakening,” he said on his show the day before the rally. The event in later years would be “indelibly marked” on the memories of children whose parents had the imagination to come along. He also promised all who would come: “You’re going to see the spirit of God unleashed.” The portrayal of us, here, now, at the critical juncture of all the past and all the future, is the indispensable trope of Beck’s most solemn self-presentations. It is easy to see how such a view could deliver comfort to people who have no strong religious beliefs to support them otherwise.

The rally was covered by the mainstream media, which gave a fair general impression of the crowd: more old than young, more rich than poor, and much more white than black. The impression may widen a little if one recounts the list of sponsors shared by Beck, Limbaugh, and Sean Hannity, who between them take up the 9 AM to 6 PM prime hours of Fox radio, and who deliver most of their ads in their own voices. Among the products are Goldline (for buying gold), Ancestry.com (for tracing your family several generations back), GoToMeeting.com (for office partners to confer without leaving home), and an offer to “refinance credit card debt in an age of government bailouts.” At intervals one also hears of the “Total Transformation Program” for children, which “works for every behavior problem imaginable.” The help with credit card debt is perhaps the most revealing of these: it is a short ad and repeated often.

All three programs speak directly about the coming elections, and Hannity for the last four months has been counting down the days. But most of the recent talking points, especially for Limbaugh’s broadcast, are drawn from the unemployment figures. Having exploited Obama’s middle name for some lazy months in 2009 before leaving it to the smaller fry of the right, Limbaugh, on a show in September, suddenly broke out: “Screw this ‘Hussein’ business! It’s Barack Hoover Obama. Look at these numbers, folks.” He feeds on bad news. Reeling off the figures, he points out that the government is “massaging these numbers…every week,” omitting people who have been out of work so long that they’ve stopped looking. When you see the numbers, he said on a recent show, “You want to laugh. And then you say to yourself, it wouldn’t be cool to laugh, and then you’re overcome but you still want to laugh.” A glimpse, there, of a sadistic streak that underlies his verbal energy. Commiseration is a forbidden weakness in the Limbaugh code, but here he was caught in a bind: laugh and you appear heartless, fail to laugh and you are one more pity-stricken liberal.

The implied equations are as follows: compassion = pretended unselfishness = hypocrisy = ambivalence. Obama’s wavering on such issues as the torture photos, the decision to pull out of Afghanistan while sending more troops to Afghanistan, the single-payer system for health insurance, what to say about big bonuses for the top guns at Goldman Sachs, the alternate cold and warm relations with Benjamin Netanyahu—all these have painted an embarrassing picture that can almost be trusted to make its own point. The opposite equations run something like this: freedom = individualism = conviction = manliness. Hence Limbaugh’s confidence in saying, only half in jest: “I don’t know how a real man—I mean, a real man—could even be a liberal, much less vote for one.”

Glenn Beck tells his listeners several times a week that Obama is leading the country into socialism and that his aggrandizement mimics that of Stalin and Hitler. To the unqualified convictions and foursquare knowledge of the excited amateur, he adds a charlatan’s unconcern whether you believe his present assertion so long as you hang around to hear his next. Limbaugh is less experimental and less doctrinal. He is redundant, resourceful, and overwhelming, mixes truth and falsehood at pleasure, but is finally all of a piece: a successor to the right-wing ideology of McCarthy, Goldwater, Reagan, and Buckley (the last of whom praised and recruited him early on).

Beck, by contrast, is an alarmingly incoherent personality. You feel that his surface sloppiness is not an accident; that he could spin away and crash at any moment. One of his favorite rhetorical gambits is: “I don’t know, this may be wrong, I’m just testing here, all this is strange to me, too. When I say I don’t know, I really mean I don’t know. I am asking you to help me.” He is endlessly confessional—regretting, for example, in an early October broadcast that “a wall” always goes up between himself and his listeners when “something important is happening in my life that I haven’t told you about.”

Like a revivalist preacher, in some moods (he is in fact a Mormon convert), he profits by not pretending to be better than he is. Thinking back on his sins—alcoholism, lying, infirmness of purpose in the first thirty-five years of his life—and his subsequent redemption, Beck cannot help also thinking of the peril in which our country stands: “hanging by a thread.” He implies without stating an identity between himself and his country. This enables him to emit (as if by a heroic effort to remove an obstruction) irregular bursts of choked-up sentiment. He wants to seem at such moments the realest person the listener has ever met. He has been down there among the ooze and sweat and odors, and he lets you know it.

When he goes awry Beck may exert his strongest enchantment. He suffers from macular degeneration and has said on the air that he may soon go blind. He has recently mentioned, too, a loss of feeling in his limbs. This knowledge lent a surpassing strangeness to an ad he delivered on a broadcast in September. The sponsor was a brand of “survival food”: condensed and preserved nutrition kits intended to be squirreled away against a time of plague, poison, mass terror, or nuclear war. In a binge-fantasia that ran over the allotted time for a break, Beck gave his pitch for the food. He used it himself and his listeners might be well advised to buy some. Then he imagined the actual occasion of its use. He, Glenn Beck, stood sentinel over his family and goods in a sealed-off shelter. Someone knocks at the door but, no, he can’t let them have his food. Fortunately, he does have his shotgun—an apparent pitch to the gun lobby—but no, it won’t work because “I can’t see the gun. I’m blind!” So the investment in Food Insurance ends up at the mercy of his neighbors and others frantic to steal it. End of commercial.

At such times Beck seems to perform as if under a plexiglass canopy. Perhaps no one is listening? But the occasional careering out of control also suggests an outlet for anarchy. Both Limbaugh and Beck recognize this as part of their appeal. They serve an instinct utterly suppressed or denied by the self-control of a public man like Obama. Yet a curious fact about both talkers is that their criticisms are almost entirely occupied with domestic politics. The choice is the more notable in Limbaugh since his father was a combat pilot in World War II, and his manner is said to be closely modeled on the way his father talked back to the TV news.

Limbaugh takes on trust the greatness and rightness of American military ventures, but he scarcely talks about them. Indeed, since the election of Barack Obama there has been remarkably little comment on America’s current wars by any of the Fox hosts. True, Hannity holds regular Freedom Concerts in honor of all who served and especially wounded veterans, but that is an exception. Why? Have they spoken with second-level people in the military and been told to lay off for now? Impotence at arms could turn into a useful accusation against Obama in 2012, and it will certainly tell more sharply if it comes as something new. At the same time, they have clearly chosen not to be cheerleaders for what they know are unpopular wars. The rewards are surer for targeting the anxieties of voters who fear the loss of their jobs. Beck in his latest causerie, Broke, appears to face the contradiction that his Fox compatriots dodge, between a demand to pay off our national debt and the wish for military supremacy: fewer wars are compatible with bigger victories, he suspects; but from now on, “we will not rebuild the rubble we reduce you to.”

In the month before the election, when Limbaugh emerged as a tribune of the unemployed, he gloated over the numbers of those out of work, then still going up. The misfortune would be blamed on Obama. Nor would any of the Democrat remedies work: Obama had appointed “more anti-capitalist people to his administration in the guise of consumer protectionists,” but he was too inexperienced to see that regulators only make things worse. Everybody knows what happens, said Limbaugh, when we have legislative gridlock. It is the best thing in the world for business. Capitalism thrives because government is not in the way, and “businesses love predictability” (including the predictability of legislative deadlock). The antigovernment dogma taken to this extreme is something new in Limbaugh. It is pandering to the Tea Party, which he did as much as anyone to instigate. And the rank and file of the movement are conscious of their debt to him. Limbaugh to a recent caller from California: “You said you’re a Tea Party in Berkeley?” Caller: “Well, there’s not many of us…. We can use one teacup to share and just pass it around.”

How broad an influence may this be taken to imply? According to Scott Rasmussen and Douglas Schoen in Mad as Hell: How the Tea Party Movement Is Fundamentally Remaking Our Two Party System,1 20 to 25 percent of voters now identify themselves as members of the Tea Party movement. Between them, the Fox hosts and the movement have also produced a formidable lumpen literature of politics and patriotic doctrine. Sarah Palin’s memoir Going Rogue 2 sold 700,000 copies in less than a week. Among the smaller movement best sellers are Mark Levin’s Liberty and Tyranny,3 with its defense of constitutional “prudence” as the author understands it, and an argument against the welfare state and “enviro-statism”; and David Limbaugh’s Crimes Against Liberty,4 an almost-explicit draft of charges of impeachment against Barack Obama (where the crimes include illegal taxation, unlimited aggrandizement of the presidency, speaking out abroad against America, and “betraying Israel”).

More idiosyncratic Fox hosts such as Bill O’Reilly and Michael Savage have contributed books of their own to the educational mission, and Limbaugh has credited Angelo Codevilla’s polemic The Ruling Class: How They Corrupted America and What We Can Do About It 5 for prompting a change in his tactics. Where he had once described Obama as an unregenerate “radical,” in the Sixties mode, Limbaugh now portrays him as a member of a phony gentry raised by affirmative action to become the nominal leader of a self-serving “elite.” These books are popular, they reduce complex issues to memorable slogans, and they are having an effect. Recent books by nonconservative and antifanatical entertainers like Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert have also sold well, yet it may be doubted that they serve as antidotes. You can learn from the comedians why the wrong ideas are funny, but you cannot learn why the wrong ideas are wrong.

Mixed in with the dogma is an uneasy proportion of sense. On October 6, Limbaugh railed against President Obama’s loose talk of the harmlessness of letting the Bush tax cuts expire. He read from an AP story that summarized Obama as reassuring a business group that “the wealthy aren’t holding off buying flat-screen TVs and other big-ticket purchases for lack of a tax cut.” To the President’s belief that the well-off wouldn’t simply “take our ball and go home” if the Bush tax cuts were allowed to expire, Limbaugh answered: “They’ve already taken their ball and gone home!” And they are staying at home, he added, to see if their money will be free for a while longer. And by the way: flat-screen TVs are made in China.

Looking back, one feels it was an astonishing negligence for the Obama White House to embark on a campaign for national health care without a solid strategy for fighting the tenacious opposition it could expect at the hands of Fox radio and TV. Month by month the jeering hosts ate away Obama’s popularity and cast doubt on his plans. His response was to go on TV talk shows himself, and out to multiple town meeting Q-and-As, but the format there was inferior, the effect diffuse, the audience always uncertain of the connection between the President’s words and his final policy. Also, by appearing to compete as a talker against the very people he scorned to recognize, Obama may have squandered some part of the luster of his office. You can get in the ring with your opponent or you can dismiss him from a dignified height. You can’t do both.

“Obamacare must be repealed.” That will be the cry of a significant section of the new Congress. “People talk about making things too simplistic,” said Limbaugh on September 23. “No, we make the complex understandable.” On the same day he gave a reason why Blue Dog Democrats were the enemy, too: “We’re not pussyfooting around here. They got a (D) next to their name, it’s history.” The stance of total hostility is unscrupulous, and if it became the norm, it could never lead back to a civilized politics. But the speaker of those words showed a desire for his party to win because politics is built up from the work of parties. It is not clear that President Obama has yet felt the same conviction.

For now, it is the impassioned radio and TV talkers who lead the Republican Party. “What you are about to hear is the fusion of entertainment and enlightenment.” But they have another message in lyrics sung with a yell by Martina McBride, which Hannity plays to open every half-hour:

Let the weak be strong, let the right be wrong

Roll the stone away, let the guilty pay, it’s Independence Day.

The plot of the song casts a garish light on the words of that refrain. A daughter is telling how her mother heroically murdered an abusive husband by burning down their house, with him in it, on the Fourth of July. The state, in this vision of things, is the abusive father, and its power to hurt the mother and daughter must now be destroyed.

Barack Obama grew up thinking government the most natural thing in the world. These are people who think government unnatural. Whatever may happen in November, their theory is coming closer to a test.

—October 28, 2010

This Issue

November 25, 2010