1.

Can Republicans defeat Obama’s health care bill by persuading the courts that mandatory health insurance is unconstitutional? On December 13, 2010, Henry Hudson, a federal judge in Virginia, declared unconstitutional the central provision of the health care reform law. Judge Hudson reasoned that the law’s command that citizens purchase health care insurance extended beyond Congress’s authority to legislate. It has long been established that Congress may regulate citizens’ economic activities, such as entering into contracts, producing or purchasing goods and services, or shipping goods across state lines. But it is entirely unprecedented, Judge Hudson said, for Congress to regulate “inactivity”—a failure to buy insurance.

Obama dismissed the opinion as just “one ruling by one federal district court.” But to others, it came as a shock. Dahlia Lithwick, Slate’s legal affairs correspondent, said that before Judge Hudson’s decision, most experts thought the legal challenges would fail in the Supreme Court by a large margin, 8–1 or 7–2, but that after the ruling, the betting is that the Court will split 5–4, with Justice Anthony Kennedy likely casting the decisive vote.1

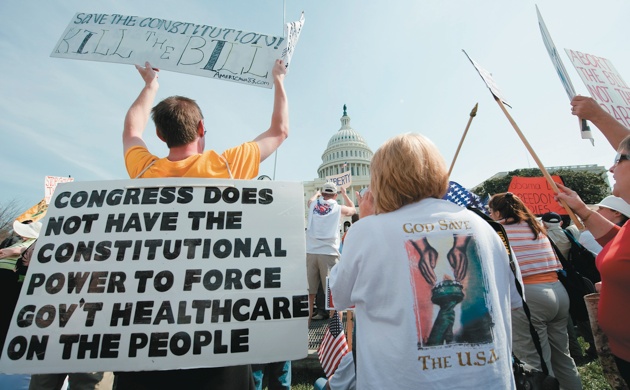

It is easy to see why commentators might expect the case to be closely divided. Health care reform has been nothing if not intensely partisan. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was passed without a single Republican vote, and Republicans in the House have already voted to repeal it. The fight over its enactment helped promote the rise of the Tea Party and the Republican victories in the midterm elections. Most of the state attorneys-general who have challenged the law’s constitutionality in court are Republicans. Several Democratic state attorneys-general have filed a brief supporting the law. So far, three judges have ruled on the merits of the challenges. Two, both appointed by Democratic presidents, upheld the act. Judge Hudson, the first to rule otherwise, is a Republican appointed by George W. Bush. Another Republican-appointed judge, Roger Vinson, has a similar case pending in Florida, and he is likely to side with Judge Hudson.1a

The roots of the ideological divide, moreover, run deep. The principal constitutional issue at stake—the extent of Congress’s authority to pass laws governing Americans’ lives—has separated conservatives and liberals since the beginning of the Republic. “States’ rights” was the South’s rallying cry in its effort to retain slavery before the Civil War, and to defend racial segregation from federal intervention thereafter. From the turn of the century through the early years of the New Deal, conservatives successfully invoked “states’ rights” to interpret Congress’s power over interstate commerce narrowly and thereby invalidate progressive federal laws designed to protect workers and consumers from big business. And the last two times that the Supreme Court struck down laws as reaching beyond Congress’s Commerce Clause power, in 1995 and 2000, the Court split 5–4, with Chief Justice William Rehnquist writing the majority decision, over dissents by Justices Stephen Breyer, David Souter, John Paul Stevens, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.2

As Judge Hudson sees it, the health care reform law poses an unprecedented question: Can Congress, under its power to regulate “commerce among the states,” regulate “inactivity” by compelling citizens who are not engaged in commerce to purchase insurance? If it is indeed a novel question, there may be plenty of room for political preconceptions to color legal analysis. And given the current makeup of the Supreme Court, that worries the law’s supporters.

But the concerns are overstated. In fact, defenders of the law have both the better argument and the force of history on their side. Judge Hudson’s decision reads as if it were written at the beginning of the twentieth rather than the twenty-first century. It rests on formalistic distinctions—between “activity” and “inactivity,” and between “taxing” and “regulating”—that recall jurisprudence the Supreme Court has long since abandoned, and abandoned for good reason. To uphold Judge Hudson’s decision would require the rewriting of several major and well-established tenets of constitutional law. Even this Supreme Court, as conservative a court as we have had in living memory, is unlikely to do that.

The objections to health care reform are ultimately founded not on a genuine concern about preserving state prerogative, but on a libertarian opposition to compelling individuals to act for the collective good, no matter who imposes the obligation. The Constitution recognizes no such right, however, so the opponents have opportunistically invoked “states’ rights.” But their arguments fail under either heading. With the help of the filibuster, the opponents of health care reform came close to defeating it politically. The legal case should not be a close call.

2.

The provision that Judge Hudson struck down requires all Americans, unless exempted on religious or other grounds, to purchase health care insurance. (Most Americans are already covered through their employment or Medicare or Medicaid, so for them this law would have no impact.) Those who do not obtain insurance must pay a penalty in the form of a special tax.

Advertisement

The individual mandate is aimed at so-called “free riders”—people who fail to get insurance, and then cannot pay the cost of their own health care when they need it. Under our current system, in which hospitals must treat people regardless of ability to pay or insurance coverage, hospitals are able to recover only about 10 percent of the cost of treating uninsured individuals. That cost is ultimately borne by the rest of us. The federal government picks up much of the tab, and hospitals and insurers pass on the rest to their paying customers in higher fees. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that in 2008 the uninsured shifted $43 billion of health care costs to others.

Without the individual mandate, the health care law’s more popular reforms—such as the bar on insurance companies denying coverage because of “preexisting conditions”—would actually make the insurance crisis worse. Knowing that insurers could not deny coverage or charge more for preexisting conditions, people could wait to buy insurance until they were sick. But then more and more of the people insured would be the sickest, defeating the very purpose of insurance—to spread the risk by creating a pool of funds that can be drawn on for payments. Premiums would skyrocket, meaning that even fewer people could afford insurance, and that would in turn induce still more people to opt out. As Wake Forest University Professor Mark Hall testified in Congress, “a health insurance market could never survive or even form if people could buy their insurance on the way to the hospital.”

This is not just an academic prediction. When in 1994 Kentucky enacted similar reforms regarding preexisting conditions, but without an individual mandate, insurance costs rose so steeply that they became untenable, and insurers pulled out of the market altogether. Kentucky was forced to repeal the reform. Initiatives in New York and New Jersey faced similar problems. In Massachusetts, by contrast, where health insurance reform was coupled with an individual mandate, the system has worked; since 2006, insurance premiums there have fallen 40 percent, while the national average has increased 14 percent.

Judge Hudson acknowledged, as do the law’s challengers, that Congress has power to regulate any economic activity that, in the aggregate, affects interstate commerce—no matter how minimal the activity’s effects are standing alone. But the decision not to buy health insurance, Hudson reasoned, is not “activity” at all. It is “inactivity.” Rather than setting rules for those who choose to engage in interstate commerce, the individual mandate compels a citizen who has chosen not to engage in commerce to do so by purchasing a product he does not want. If Congress can regulate such “inactivity,” Hudson warned, there would be no limit to its powers, contravening the bedrock principle that the Constitution granted the federal government only limited powers.

Judge Hudson’s reasoning is not without precedent—but the precedents that his rationale reflects have all been overturned. In the early twentieth century, the Supreme Court ruled that the Commerce Clause authorized Congress to regulate only “interstate” business, not “local” business; only “commerce,” not production, manufacturing, farming, or mining. The Court also ruled that Congress could regulate only conduct that “directly” affects interstate commerce, not conduct that “indirectly” affects interstate commerce. Like Judge Hudson, the Supreme Court warned that unless it enforced these formal categorical constraints, there would be no limit to Congress’s power. Thus, for example, in 1936, the Court struck down a federal law that established minimum wages and maximum hours for coal miners, reasoning that mining was local, not interstate; entailed production, not commerce; and had only “indirect” effects on interstate commerce.3 Using this approach, the Court invalidated many of the laws enacted during the early days of the New Deal.

Around 1937, however, the Court reversed course. It recognized what economists (and the Court’s dissenters) had long argued, and what the Depression had driven home—that in a modern-day, interdependent national economy, local production necessarily affects interstate commerce, and there is no meaningful distinction between “direct” and “indirect” effects. In the local, agrarian economy of the Constitution’s framers, it might have made sense to draw such distinctions, but in an industrialized (and now postindustrialized) America, the local and the national economies are inextricably interlinked.

As a result, Congress’s power to regulate “interstate commerce” became, in effect, the power to regulate “commerce” generally. The Court rejected as empty formalisms the distinctions it had previously drawn, between local and interstate, between production and commerce, and between “direct” and “indirect” effects. Since 1937, the Supreme Court has found only two laws to be beyond Congress’s Commerce Clause power. Both laws governed noneconomic activity—simple possession of a gun in a school zone and assaults against women, respectively—and were unconnected to any broader regulation of commerce.4 But the Court has repeatedly made clear that Congress can regulate any economic activity, and even noneconomic activity where doing so is “an essential part of a larger regulation of economic activity.”

Advertisement

On this theory, the Supreme Court has upheld federal laws that restricted farmers’ ability to grow wheat for their own consumption and that made it a crime to grow marijuana for personal medicinal use, even though in both instances the people concerned sought to stay out of the market altogether.5 The Court reasoned that even such personal consumption affects interstate commerce in the aggregate by altering supply and demand, and that therefore leaving it unregulated would undercut Congress’s broader regulatory scheme.

Under these precedents, a citizen’s decision to forgo insurance, like the farmer’s decision to forgo the wheat market and grow wheat at home, easily falls within Congress’s Commerce Clause power. When aggregated, those decisions will shift billions of dollars of costs each year from the uninsured to taxpayers and the insured. As a practical matter, there is no opting out of the health care market, since everyone eventually needs medical treatment, and very few can afford to pay their way when the time comes. (Those who refuse all medical treatment for religious scruples are an exception, but they are exempt from the mandate.) That one might affix the label “inactivity” to a decision to shift one’s own costs to others does not negate the fact that such economic decisions have substantial effects on the insurance market, and that their regulation is “an essential part of a larger regulation of economic activity.”

3.

Another part of the Constitution, the “Necessary and Proper Clause,” provides even more well-established support for Congress’s action. That catch-all provision authorizes Congress to enact laws that, while not expressly authorized by the Constitution’s specific enumerated powers, are “necessary and proper” to the exercise of those powers. In one of the Court’s most important decisions, McCulloch v. Maryland, written by Chief Justice John Marshall nearly two hundred years ago, the Court unanimously ruled that this provision must be given a broad reading, permitting any laws that are “convenient” or “rationally related” to the furtherance of an express power.6 In that case, the Court upheld Congress’s creation of a national bank, even though the authority to do so is nowhere expressly provided, because a national bank was rationally related to the exercise of Congress’s other powers, including the power to coin money and tax and spend. By the same token, because the individual mandate is rationally related to Congress’s conceded power to regulate health insurance, it is “necessary and proper.”

The wide reach of the Necessary and Proper Clause was reaffirmed just last year when, in a 7–2 decision joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Kennedy and Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court upheld a federal law authorizing civil commitment of federal prisoners who are sexual predators, even though no provision expressly authorizes Congress to do so.7 The Court explained that as long as there is some initial link to an explicitly enumerated power in the Constitution, the Necessary and Proper Clause authorizes actions many steps removed from that power. Thus, the Court reasoned, Congress may pass criminal laws “rationally related” to any of its other enumerated powers. It may then build prisons to house those convicted, enact rules to govern prisoners, and provide civil commitment to protect the community from those leaving federal prison—even though the Constitution expressly authorizes none of these actions.

If the Necessary and Proper Clause supports such an extended string of implied powers, there can be little dispute that it authorizes the individual mandate. Congress undoubtedly has the authority to regulate health insurance under the Commerce Clause, so the individual mandate is “necessary and proper” as long as it is “rationally related” or “convenient” to that larger project. It clearly passes that test, as it is integral to avoiding a very large increase in health insurance premiums. Judge Hudson concluded, however, that because in his view the mandate was not permissible under the Commerce Clause, it could not be authorized by the Necessary and Proper Clause. That approach renders the latter clause meaningless, and directly contravenes McCulloch v. Maryland.

Finally, the individual mandate is also sustainable under Congress’s independent power to tax. President Obama insisted on a Sunday talk show that the mandate was not a tax, but the Court has long ruled that the validity of a law turns not on what label is attached to it, but on what it does. The individual mandate collects revenue from individuals as part of their income tax. It is expected to generate $4 billion annually, which will help the federal government defray the health care costs the uninsured fail to pay.

Judge Hudson deemed the law to be a penalty, not a tax, citing a 1922 decision that invalidated a federal tax on child labor on this ground.8 But that case, which dates from the same pre–New Deal era when the Court was narrowly construing Congress’s Commerce Clause powers, rested on another formalist distinction, since rejected, between laws that collect revenues and laws that regulate behavior. As with the pre–New Deal Commerce Clause distinctions, the Court has since abandoned this distinction, recognizing that taxes inevitably have regulatory effects by increasing the cost of the activity that is taxed. Thus, according to modern constitutional jurisprudence, a tax law is valid if it raises revenue and its regulations are reasonably related to the exercise of the taxing power.

Congress plainly can tax for the purpose of providing health insurance. It does so already, through Medicare and Medicaid. Had it simply expanded these programs to provide universal care, there would be no question that its actions would be permissible under the taxing power. Similarly, it indisputably could have granted tax credits to those who purchase health care, and withheld them from those who do not. Imposing the tax directly on free riders is no less an exercise of the taxing power.

Judge Hudson’s concerns that upholding the law would lead to unlimited federal power are wildly exaggerated. A decision to sustain the individual mandate would not mean that Congress could require all Americans to exercise or eat only healthy food, as some have suggested. The individual mandate regulates an economic decision that is in turn an essential part of a comprehensive economic regulation of the interstate business of insurance. And health care is a unique commodity, in that virtually everyone will eventually need it; along with taxes and death, a trip to the doctor is one of life’s inevitabilities. Thus, to say that Congress can require an individual to purchase insurance or pay a tax does not signal the end of all meaningful limits on federal power.

In short, Congress had ample authority to enact the individual mandate. Absent a return to a constitutional jurisprudence that has been rejected for more than seventy years, and, even more radically, an upending of Chief Justice Marshall’s long-accepted view of the Necessary and Proper Clause, the individual mandate is plainly constitutional.

4.

Near the end of his decision, Judge Hudson writes: “At its core, this dispute is not simply about regulating the business of insurance—or crafting a scheme of universal health insurance coverage—it’s about an individual’s right to choose to participate.” Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, who brought the suit, echoed that point the day the decision came down, insisting that “this lawsuit is not about health care. It’s about liberty.” But that is exactly what the case is not about. A decision that Congress lacks the power to enact the individual mandate says nothing about individual rights or liberty. It speaks only to whether the power to require citizens to participate in health insurance, a power that states indisputably hold, also extends to the federal government. The framers sought to give Congress the power to address problems of national or “interstate” scope, problems that could not adequately be left to the states. The national health insurance crisis is precisely such a problem. The legal question in the case is about which governmental entities have the power to regulate; not whether individuals have a liberty or right to refuse to purchase health care insurance altogether.

But Judge Hudson and Ken Cuccinelli’s misstatements are nonetheless telling. Opposition to health care reform is ultimately not rooted in a conception of state versus federal power. It’s founded instead on an individualistic, libertarian objection to a governmental program that imposes a collective solution to a social problem. While Judge Hudson’s reliance on a distinction between activity and inactivity makes little sense from the standpoint of federal versus state power, it intuitively appeals to the libertarian’s desire to be left alone. But nothing in the Constitution even remotely guarantees a right to be a free rider and to shift the costs of one’s health care to others. So rather than directly claim such a right, the law’s opponents resort to states’ rights.

In this respect, Judge Hudson and the Virginia attorney-general are situated squarely within a tradition—but it’s an ugly tradition. Proponents of slavery and segregation, and opponents of progressive labor and consumer laws, similarly invoked states’ rights not because they cared about the rights of states, but as an instrumental legal cover for what they really sought to defend—the rights to own slaves, to subordinate African-Americans, and to exploit workers and consumers.

Here, too, opponents of health care reform are not really seeking to vindicate the power of states to regulate health care. Rather, they are counting on the fact that if they succeed with this legal gambit, the powerful interests arrayed against health care reform—the insurance industry, doctors, and drug companies—will easily overwhelm any efforts at meaningful reform in most states. Unless the Supreme Court is willing to rewrite hundreds of years of jurisprudence, however, they will not succeed.

—January 27, 2011

This Issue

February 24, 2011

-

1

It is not certain that Judge Hudson’s decision will reach the Supreme Court. He found that Virginia had standing to sue because its legislature had enacted a law giving citizens the right not to buy health insurance, as part of a national campaign by health care reform opponents to create obstacles in the states. It is far from clear that a state can manufacture a dispute by enacting such a law, so it is possible that the case could be thrown out on appeal for failing to present a concrete controversy. However, at some point the health care law will plainly be subject to a constitutional challenge, at a minimum by any individual who objects to being required to purchase health insurance or pay the tax. So whether in this case or some other, the courts will eventually have to address the law’s constitutionality. ↩

-

2

United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000); United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995). ↩

-

3

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238 (1936). ↩

-

4

See cases cited in note 2. ↩

-

5

Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005); Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111 (1942). ↩

-

6

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (Wheat.) 316 (1819). ↩

-

7

United States v. Comstock, 130 S. Ct. 1949 (2010). ↩

-

8

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U.S. 20 (1922). ↩