Winslow Homer, an artist of conceptual originality and high-wire technical audacity, once described the historical component of one of his paintings, of a fortified harbor at night, as the “stern facts.” During his long and varied career, Homer (who died in 1910 at the age of seventy-four) painted some of the most familiar images in all of American art. Many people today would recognize his incomparable sporting pictures of leaping trout and drowning deer, or his heroic seascapes of hard-bitten fisherfolk and intrepid rescuers in violent storms. His dazzling watercolors of the tropics have had a recent vogue—brushy, highly colored vignettes of palms and poinsettias, with an unerring feel for the possibilities of the medium that recalls the masters of Japanese painting, which recent research suggests he was familiar with. There is often an element of risk in Homer’s paintings, either in the subject depicted or in the medium adopted, as in the do-or-die decisions of watercolor.

Danger is at the heart of a pungent and enigmatic picture like The Gulf Stream (1899), which portrays a bare-chested African-American man adrift in a rudderless boat with a broken mast, amid a choppy sea seething with menacing, open-jawed sharks, and with a threatening waterspout on the horizon. An over-the-top painting like this retains its magnetic hold on viewers, even as scholars continue to debate its elusive meanings. Does the picture have something to say about the embattled status of blacks around the time of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), as some scholars have suggested, or is it simply a naturalistic picture of a fisherman in deep trouble?1 When asked by a baffled prospective buyer for an explanation of The Gulf Stream, Homer, who was famously taciturn, replied, “I regret very much that I have painted a picture that requires description.”

But it was as a painter of historical events that Homer first made his mark, and specifically as a recorder of the “stern facts” of the American Civil War. Sent to the front by Harper’s magazine during the fall of 1861, he was embedded, as we would now say, with Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. At a time when photographers, like those hired by Mathew Brady, required long minutes for their exposures and hence “still” subjects, artists like Homer were counted on to convey the movement and suspense of the battlefield.

Homer was thirty-one when he first traveled to Virginia, and almost as new to the job as the young recruits he sketched. He had moved to New York two years earlier, in 1859, after completing an apprenticeship with a lithographer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father, an importer of hardware, had hoped for a more prestigious education for his sons when he installed them in a house near the Harvard campus. Charles Homer “wiggled through Harvard,” as he put it, but his younger brother Winslow, encouraged, one assumes, by their mother, a skilled watercolorist, “wanted to draw.” He described his monotonous apprenticeship, designing covers for sheet music and the like, as “slavery,” and escaped to the more lucrative markets for illustrators in New York, while also taking classes at the National Academy of Design.

Homer’s real college, as many commentators have noted, was the war. One can see in the drawings and prints that resulted from his first stint at the front with what stunning speed—faster, it might be said, than the hapless General McClellan—he grasped the new realities of the conflict. He dispensed with the hackneyed imagery of theatrical battle charges, drawn from Meissonier and other purveyors of the Napoleonic campaigns, and zeroed in, instead, on the lethal machinery of modern warfare: the rifle of the youthful Sharpshooter (1863), for example, in his first documented oil painting.

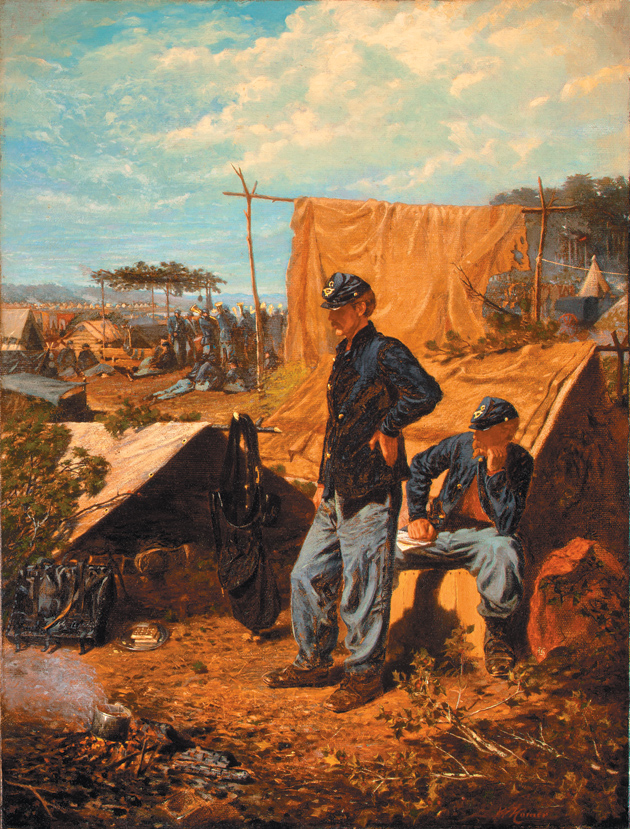

But it was the human face of the war that Homer most insisted on. Among the first oil paintings that he exhibited in New York was Home, Sweet Home (circa 1863), which depicts soldiers listening to a band in the distance. The engaging painting draws from journalistic conventions. There is a great deal of information about camp life in the matter of tents and saddlebags, a muted harmony of complementary blue and orange expanses, and little in the way of visual ambiguity. One may be surprised that the picture was singled out by approving critics for its lack of “clap-trap” and “sentimentality.” What could be more sentimental than pensive soldiers listening yearningly to a band playing “Home, Sweet Home”? But there’s an astringent wit to the picture in the contrast between the current “home” of the soldiers—low tents and a small pot over a fire with a piece of hardtack on the side—and the emotions presumably summoned up by the distant music.

Homer was among the first artists to recognize that an adequate account of the war was incomplete without the inclusion of its African-American participants. With characteristic speed, he moved from portraying racist caricatures readymade in the popular press—woolly-headed banjo players and bug-eyed dancing cooks—to rendering powerful studies showing the human dignity of the black soldiers. In a pioneering book on these images, called Winslow Homer’s Images of Blacks: The Civil War and Reconstruction Years (1988), written in conjunction with Karen C.C. Dalton, the Duke historian Peter H. Wood singled out a painting of 1865–1866 in what he called Homer’s “evolution”:

Advertisement

If any one image epitomizes Homer’s Civil War evolution and his increasing willingness to place substantial black figures at the center of his work, it is a little-known painting of a slave woman that was discovered in a New Jersey attic in the early 1960s, nearly a century after its completion.

The painting in the attic, as subsequent research brought to light, was titled Near Andersonville.

The visual format of Near Andersonville, although Wood does not say so, is remarkably similar to Home, Sweet Home. In both pictures, a standing figure in three-quarter view, with head covered, takes up the center of the painting. Framed by the trappings of a makeshift and uninviting home, this central figure seems to be thinking about what a group of uniformed soldiers, in the upper-left distance, are up to. Both pictures have a dominant brown tonality, relieved by bits of red on the human figures, and by the partially clouded blue of the sky.

In his new book, Wood asks us to look closely at every detail of Near Andersonville: the young slave woman, dressed in a patterned red turban and white apron, standing on the threshold of a simple brown wooden building; the plump brown gourds and empty bucket that lie on the ground and the wooden shelves on either side of her. Her hands—one on her hip and one hanging down—are positioned like the hands of the standing soldier in Home, Sweet Home. Just as the gold insignia on the soldier’s hat is level with the metallic glint of the band instruments, the woman’s red turban is level with a red Confederate flag carried by a guard escorting Union prisoners.

These complex paintings of Homer’s first major phase seem to establish something analogous to the split screen of movies and television, or the thought bubbles of comic strips. We can guess the mixed reactions of the soldier listening to the distant band playing “Home, Sweet Home.” But what, we wonder, is the relation of the pensive slave woman to the Union captives being led away to the death camp at Andersonville in southwest Georgia, a prison so notorious for its hideous overcrowding, disgusting sanitation, and appalling death rate (nearly a third of the roughly 41,000 men imprisoned there died in captivity) that its commanding officer, Captain Henry Wirz, was the only Confederate official executed for war crimes after the war? Peter Wood tries to provide answers in Near Andersonville: Winslow Homer’s Civil War, comprised of three lectures about the painting, initially delivered at Harvard.

The lectures give, first, a dramatic account of the discovery of “The Picture in the Attic”; second, a vivid account of Homer’s experience as a correspondent “Behind Enemy Lines,” in which Wood speculates, in passing and with scant evidence, that Homer, a deeply private man who never married, might have suffered from post-traumatic stress2; and, third, an extended and at times emotionally overwrought interpretation of “The Woman in the Sunlight.”

The first two lectures are well researched and lively to read. In “The Picture in the Attic,” Wood, somewhat in the manner of the popular television series Antiques Roadshow, tries to resolve the mysteries surrounding the picture’s provenance. His research eventually led him to identify a young woman called Louise Kellogg as the first owner of the painting. Kellogg, Wood has discovered, joined the corps of idealistic young teachers known as “Gideon’s Band,” who traveled to the South after the war to teach the children of freed slaves. Kellogg worked near the South Carolina coast where, Wood speculates, she may have encountered Homer’s younger brother, Arthur, who patrolled the area on a naval vessel. Kellogg, about whom very little is known, died of tuberculosis soon after acquiring the painting, which then passed into the hands of successive generations of her family.

Wood goes on to offer a fresh perspective on Homer’s upbringing, especially with regard to the militant abolitionism of midcentury Cambridge. We learn that Homer’s father attended Lyman Beecher’s school, and “would have met” his children Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, both of whom became prominent abolitionists. We are reminded that Homer depicted, in his early illustrations, many of the key events leading up to the Civil War, such as Frederick Douglass being dragged from the stage in Boston and the caning of Senator Charles Sumner by a Southern representative in the Senate chamber. Wood argues that the atmosphere of Harper’s, with its corps of pro-Union illustrators such as Thomas Nast, would have encouraged a view of American painting as carrying “veiled” political commentary.

Advertisement

In his culminating section, Wood tries to combine what he has learned about the provenance of the painting and Homer’s early career to advance a fresh interpretation of Near Andersonville. The Union captives in the background, Wood believes, are victims of General George Stoneman’s disastrous raid of July 1864. General William Tecumseh Sherman, frustrated in his attempts to seize Atlanta, had sent Stoneman on a mission to destroy Confederate supply lines south of the city; Stoneman had proposed an additional mission, to free Union captives at Andersonville. The bungled raid led to an ironic result, as many more Union captives, including Stoneman himself, were led off to prison. The picture may also allude, in Wood’s view, to controversial efforts to arrange an exchange of prisoners, which had broken down on an issue involving race. Confederate negotiators refused to include African-American prisoners in such exchanges, regarding them as runaways rather than soldiers. All these things, Wood suggests, might be on the pensive slave woman’s mind in Near Andersonville.

In Winslow Homer’s Images of Blacks, Wood and Dalton adopted a way of interpreting the picture that might be described as allegorical, where concrete objects refer to abstract ideas. The boards intersecting in an oblique angle at the woman’s feet had, in the authors’ view, a specific allegorical significance: “Homer’s woman stands at a crucial fork, as symbolized by the diverging boards in front of her.” Similarly, the gourds, according to Wood and Dalton, “signify her hope of freedom,” since escaping slaves were instructed to follow the Big Dipper, also called “the Drinking Gourd,” toward the North and freedom.

In his new book, Wood enumerates many more emblems of freedom. The woman’s turban, he suggests, “hints at what is known as the Phrygian freedom cap,” a symbol of liberty that “appeared on virtually every silver coin of the United States.” With the woman’s dark dress, Homer “may wish to suggest the front-buttoned ‘Garibaldi blouse’ with its distinctive sleeves.” The reader can’t help but notice that the turban doesn’t really look much like a Phrygian freedom cap, and who in the world would think of Garibaldi when contemplating the woman’s white apron?

Two other suggestions are advanced with more conviction, though again with shaky evidence. The “diverging boards” at the woman’s feet are now identified as “planks,” while the threshold on which she stands is renamed a “platform.” In ten pages of analysis concerning the contested presidential election of 1864, when Lincoln’s campaign stalled in parallel with Sherman’s march toward Atlanta, Wood argues that this painting is actually meant to invoke the party “platforms” and their various “planks” in the campaign, and specifically their relation to the future of black people in America. Hardly have we digested this complicated visual and verbal pun when Wood announces his discovery, based on certain otherwise “inexplicable” wrinkles in her apron, that the woman is pregnant, possibly “carrying her master’s child (perhaps even the child of her own father).” The gourds represent her absent children, and so on.

Does anyone really believe that Near Andersonville was meant to be interpreted in this rebus-like fashion? Wood ascribes the initial neglect of the painting, when it first entered the collection of the Newark Museum in 1966, to two causes that might seem to be self- canceling: race riots in the Newark streets and the “cloistered” isolation of art historians from political issues. Potential viewers were either too consumed by racial conflict or too oblivious to it to “make sense of this troublesome picture” in their midst.

During the intervening three decades, as other images of African-Americans in Homer’s pictures—the wondrous Dressing for the Carnival (1877), for example, or the resting teamsters in the incisive Bright Side (1865)—have received a great deal of attention, it must be puzzling to Wood that Near Andersonville remains on the sideline in discussions of the artist. It wasn’t included in the huge retrospective of Homer’s work at the National Gallery and other prominent museums in 1995, nor was it mentioned in the exhibition catalog.3

Of course, there’s a simpler reason to explain the neglect of Near Andersonville. Despite its simple charm and respectful attitude toward its central figure, it simply isn’t one of Winslow Homer’s strongest paintings. Even if we accept all the emblems of liberty that Wood has forced, like so much stuffing, into our understanding of the picture—the Phrygian caps and Garibaldi blouses—and even if we agree that “the woman in the sunlight” may remind us of “similar images that portray a strong but illiterate woman of color, standing in a doorway in present-day Afghanistan or Sudan, wearing a different head scarf, and eyeing distant soldiers”—even then we might feel that the picture itself is just a little too straightforward, too obvious in its narrative (a slave woman sorrowfully beholds a defeat of her liberators), to compel our most exacting attention. Its visual interest is modest; stylistically, it seems to owe more to Millet and his poignant peasant “types” than to a fresh engagement with American realities.

And if we admire Homer as he wished to be admired, for his avoidance of claptrap and sentimentality, we may fear that Wood has done him a disservice, by reintroducing sentimentality into his discussion of the picture. We miss the ironic edge. “At last all of us—American historians, art scholars, and the public at large—are finally in a position to appreciate more fully this remarkable woman.” Perhaps. But at the end of Wood’s paean to Near Andersonville, the reader may feel that a wash of sentiment has threatened to submerge the “stern facts.”

This Issue

March 24, 2011

-

1

In The Rape of the Masters: How Political Correctness Sabotages Art (Encounter, 2004), Richard Kimball takes Albert Boime to task for claiming, in an influential article of 1989, that The Gulf Stream is “an allegory of the black man’s victimization at the end of the nineteenth century.” He also mentions Peter Wood’s essay “Waiting in Limbo: A Reconsideration of Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream” (1981) as an earlier attempt to enlist Homer as a sympathetic commentator on African-American experience. Kimball, against such allegorical interpretations, maintains that Homer painted sharks circling around a derelict boat because “he thought it would make for a dramatic motif. It’s that simple.” ↩

-

2

Homer’s mother reported that he returned after two months at the front “so changed that his best friends did not know him.” On the basis of this remark and a few paintings of wounded veterans, Wood speculates that “her artistic son may have papered over what we now call posttraumatic stress. Some have explained Homer, the private bachelor of later years, as a taciturn Yankee or a closeted homosexual. I think it makes equal sense to suggest that shadows of combat remained a lasting part of Homer’s life.” ↩

-

3

Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. and Franklin Kelly, Winslow Homer (National Gallery of Art (Yale University Press, 1995). See also the articles by Lucretia Giese (with an extended study of The Bright Side) and David Park Curry (on Dressing for the Carnival) in Winslow Homer: A Symposium, edited by Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. (National Gallery of Art/University Press of New England, 1990). These writers are wary of ascribing the broad humanist themes to Homer’s paintings that Wood finds in them. Giese reminds us that “Homer’s position on racial issues is not known,” while Curry notes that “Homer did not see his black subjects as individuals. They are types.” Cikovsky’s discussion of Homer as a painter of lethal machinery and ironic distance has helped inform the ideas in this essay. ↩