Imagine a festive dinner near Topeka during the fall of 1879 to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Kansas Territory, with Walt Whitman as a featured speaker. Partially paralyzed by a stroke and described as “reckless and vulgar” by The New York Times—Leaves of Grass was soon to be banned for indecency by the Boston district attorney—Whitman, who had just turned sixty, may well have wondered why he, instead of some respectable graybeard like Emerson, was invited. Was it because he had defended John Brown, the hero of free-soil Kansas? Or was it hoped that a visit might inspire something like his 1871 “Song of the Exposition,” in which Whitman admonished the Muse:

Migrate from Greece and Ionia,

Cross out please those immensely overpaid accounts,

That matter of Troy and Achilles’ wrath…

For know a better, fresher, busier sphere, a wide, untried domain awaits, demands you.

Like, say, Kansas.

Upon arrival Whitman was mortified to learn that he was indeed expected to deliver a poem at the gathering—he had written none. Hastily drafting a speech instead, he found the boisterous company of a group of college boys from nearby Lawrence so congenial that he missed the commemorative dinner altogether. He later published the speech anyway, a vapid prose poem in praise of the prairies, “that vast Something, stretching out on its own unbounded scale, unconfined…combining the real and ideal, and beautiful as dreams.”

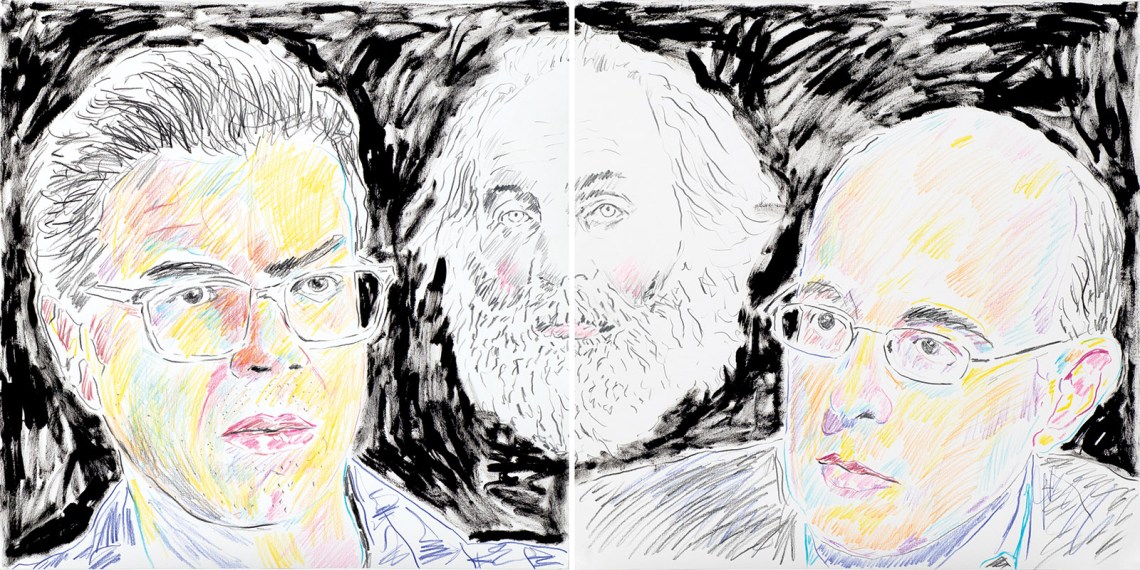

Ben Lerner’s most recent novel, The Topeka School (2019), is loosely based on his own coming of age as a poet in his hometown; he now lives and teaches in Brooklyn, where Whitman launched his career. The chiasmus—Whitman in Topeka, Lerner in Brooklyn—must have proved irresistible, even if, as Lerner ruefully notes in one of his poems, “I have almost none of the characteristics of the well-made man Walt Whitman enumerates.” And yet Whitman is everywhere in Lerner’s new book of poetry, The Lights, which gathers fifteen years of work and represents, among other things, a Whitmanian embrace of New York amid the ravages of the pandemic.

Lerner directly engages Whitman in “The Dark Threw Patches Down upon Me Also,” an impressive long poem with a title drawn from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” Best known for his boosterish optimism (“The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem,” he proclaimed in the preface to Leaves of Grass), Whitman can be more moving in the minor key, as when he confesses, in a section of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” that Lerner alludes to, that he “was wayward, vain, greedy, shallow, sly, cowardly, malignant,/The wolf, the snake, the hog, not wanting in me.”

In “The Dark Threw Patches,” Lerner describes the 1879 dinner scene in Kansas, as recounted in Specimen Days, Whitman’s sprawling, collage-like autobiography:

My favorite part of the book:

he’s in Topeka and is supposed to read

a poem to twenty thousand people, instead

decides to write a speech he fails to give

because he’s having a great time at dinner,

so he just puts the speech in the book where we

can read it at our leisure, makes you wonder

if he actually sent the letter he included

written to a dead soldier’s mother. Whitman:

poetry replaced by oratory addressed

to the future, the sensorial commons

abandoned for a private meal.1

The flexible blank verse allows quick shifts from the colloquial (“having a great time,” “makes you wonder”) to the near professorial (“the sensorial commons/abandoned for a private meal”). Coleridge’s conversation poems come to mind, but a more direct inspiration is John Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror.” One section of Lerner’s poem, an unpacking of Bastien-LePage’s painting of Joan of Arc at the Metropolitan Museum, is something of an homage to Ashbery’s poem. “She reaches her left arm out, maybe for support/in the swoon of being called,” Lerner writes. And Ashbery:

As Parmigianino did it, the right hand

Bigger than the head, thrust at the viewer

And swerving easily away, as though to protect

What it advertises.

In his superb 2014 novel 10:04, a Sebaldian hybrid of autobiography and fiction, Lerner (or his fictional stand-in) is awarded a residency at the artists’ retreat in Marfa, Texas. The only book he takes along, since he plans to teach it in the fall, is the Library of America edition of Whitman, “its paper so thin you could use it to roll cigarettes.” He composes a long poem, “a weird meditative lyric in which I was sometimes Whitman,” fragments of which are reproduced in the novel. This is the same poem we can now read in its entirety in The Lights.

A major pleasure of reading Lerner is this kind of cross-reference. It can also be a challenge. If 10:04 is read first, it offers a clarifying context for the otherwise somewhat oblique “The Dark Threw Patches,” where Marfa is never mentioned by name, leaving the reader to puzzle over lines like “I am an alien here with a residency.” But what brings “The Dark Threw Patches” to life is partly this obliquity, “tell[ing] it slant,” in Emily Dickinson’s phrase. The reader may or may not recognize, from various details, the moment when Lerner’s voice merges briefly with that of the unnamed Washington Roebling, the engineer who oversaw the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, or that Roebling and one of the two “Cranes” mentioned (the unnamed Hart) lived in the same apartment building some fifty years apart.

Advertisement

Similarly, I found I needed more context for the opening lines of a poem addressed to the Russian revolutionary Victor Serge:

The light that changes

The light that goes out

When you pass under it

The unsafe intersection

And the ghost bike.

Then I read Lerner’s fine essay in these pages on Serge, described as a lover of light, which helped me get my bearings in the poem.2 Other poems remained closed to me, as when Lerner asks, without a question mark, “Is recumbency necessary to facilitate analytic revelry,” or when he writes, perhaps facetiously, “At least the white poets might be trying to escape, using/the interplanetary to scale/down difference under the sign of encounter.”

In his first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station (2011), with its title drawn from Ashbery, Lerner describes the experience of reading the poet’s early work: “Ashbery’s flowing sentences always felt as if they were making sense, but when you looked up from the page, it was impossible to say what sense had been made.” As Lerner writes in a passage in The Lights, “I think you need either meaning or a sense that it has fled, especially when you look up.” It can sometimes seem that there is more verbal pressure in Lerner’s novels, in which there is an imperative to make basic sense, than in his poetry, where it can feel as though the meaning has gone a little too far astray.

Perhaps for that reason, some of the strongest work in The Lights is an array of prose poems. “The Voice,” for example, is built around a cascade of his father’s sayings, such as “Sometimes you have to kill the bee…. Sometimes you have to press the flower.” Growing up, Lerner believed these were proverbs that connected him “to Ukraine and Judaism, personal and collective histories.” In fact, his father, who also wrote poetry, invented them, thus creating what Lerner calls “a toy folk tradition.” A toy folk tradition, Lerner implies, might be a workable definition for poetry. His wife begins to coin deft proverbs of her own: “Seven days from now is not a future.”

Fatherhood and family are major themes in The Lights. His two daughters demand to know, since he claims to be a poet, whether he has met Amanda Gorman. When they ask why his poems don’t rhyme, he ends the poem, dutifully, with a childlike couplet: “Though it wasn’t a game or song/they played and sang along.” In another poem, the girls collect a firefly near the Camperdown elm in Prospect Park, celebrated in a poem by another of Lerner’s inspirations, Marianne Moore, and one of the girls asks “if it makes honey/That glows in the dark.”

In The Topeka School Lerner leads his family in protests against Trump’s immigration policies, just as in The Lights he invokes the protests in Brooklyn after the murder of George Floyd. As a politically engaged writer, he admires Serge, a poet who took sides, and is distrustful of Whitman’s embrace of North and South in “a war you love all sides of.” He mentions that the causes of the war seem to have meant nothing to Whitman, who “almost never/mentions race, save to note there are plenty/of Black soldiers.” Lerner is also disturbed by the way Whitman aestheticizes, even eroticizes, the agonies of the young men he ministers to in Washington’s makeshift hospitals during the war: “It seems to be pleasurable/for him when the moon makes radiant patches/for a death-stricken boy to moan in.”

If Lerner is tough on Whitman—“I’ve been worse than unfair,” he admits—the conclusion of the poem is conciliatory, as he concedes that Leaves of Grass “is among the greatest poems” and only fails for the reason all poems fail: “Because it wants to become real.” He assumes a Whitmanian stance by the East River, channeling an ecstatic perspective in the beautiful closing lines of the poem:

And yet: look out from the platform, see

mysterious red lights move across the bridge

in a Brooklyn I may or may not return to,

phenomena no science can explain,

wheeled vehicles rushing through the dark

with their windows down, streaming music.

Four years after his botched star turn in Kansas, Whitman was invited to another unlikely gathering. At the behest of a junior lecturer at an obscure college in upstate New York, five distinguished writers gathered on a June weekend in 1883 for what was billed as “a public conversation about the future of America.” It seemed an opportune time for such a discussion. A financial meltdown had followed the ugly “Compromise of 1877” in the Electoral College, which ended the racially progressive policies of Reconstruction in exchange for Republican control of the White House. Amid such national turmoil, why not gather a representative group of writers—those unacknowledged legislators of the world, in Shelley’s phrase—to suggest some workable direction forward?

Advertisement

Hartford neighbors Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe arrived together by train at the whistle-stop of Auburn, between Albany and Buffalo, where they were joined by Frederick Douglass, Herman Melville, and Whitman for what later came to be known as the Auburn Conference. After college administrators weighed in, two other writers were included in the panel discussions: the Lost Cause advocate and former Confederate general Forrest Taylor, son of Zachary, and the popular romance novelist Lucy Comstock. Among the spectators was the unknown poet Emily Dickinson, who pressed her oblique poems on anyone who might read them, including Melville.

The Auburn Conference is pure fantasy, of course—Lucy Comstock and Forrest Taylor never existed, and the conference itself never occurred. It’s all spun from the imagination of the versatile novelist and Grammy Award–winning music critic Tom Piazza, a principal writer for the television series Treme. The concept of a debate-based novel is as old as Plato’s Symposium, which Piazza alludes to. Günter Grass’s The Meeting at Telgte (in which seventeenth-century poets and intellectuals argue about the future of Germany while the Thirty Years’ War rages) is a more recent example and shares Piazza’s implicit parallel between a fraught period in the past and our own. When the organizer of the symposium remarks, “I have come to the conclusion that the entire nation is insane,” it’s easy to imagine Piazza feeling the same way today.

The Auburn Conference verges on satire, and satirists trade in exaggeration and stereotypes. In Piazza’s telling, Melville is depressed. Whitman chases boys—remember those distracting college kids in Kansas. Twain is a drunk. Stowe is a scold. Dickinson is a shy control freak. (“Over the long years, she had become the private virtuoso of a species of control which had, finally, come to control her.”) Only Douglass, noble and forthright throughout, is spared such indignities. Piazza takes liberties with the historical record. Scholars have looked in vain for evidence that Douglass was familiar with Melville’s Benito Cereno (1855), a fictionalized account of a rebellion aboard a slave ship off the coast of Chile.3 Piazza’s Douglass calls the novella Melville’s masterpiece, marveling at the writer’s “insight into the mechanism of deception and treachery” essential for preserving the institution of slavery, and “the way in which the mechanism makes prisoners of all concerned.”

Likewise, Piazza imagines Dickinson, who would never have traveled to a gathering like the Auburn Conference, actually reading Leaves of Grass instead of dismissing it with her well-known remark, in answer to a question from her literary friend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, that she was “told it was disgraceful.” (Higginson himself wrote disdainfully, “It is no discredit to Walt Whitman that he wrote Leaves of Grass, only that he did not burn it afterwards.”) Asked in Piazza’s novel whether she likes the poems, she replies, “There is quite a lot of wind blowing these leaves around.” A poet she does admire, in Piazza’s account, is Gerard Manley Hopkins, though the poem she remembers, “The Windhover,” wasn’t published until 1914, long after her death.

Playing fast and loose with the historical record is fine if the imaginative payoff is commensurate. But just as I sometimes longed for the prosaic virtues of clarity and explanation when reading Lerner, I sometimes wished for more poetic—more creatively inventive—verve in Piazza’s novel. He might have given his characters, especially Dickinson and Stowe, more freedom, more flair, instead of playing them for laughs. There is something a little wooden in the way he cobbles together his controversies. Not everyone can write a fully embodied historical novel like Ragtime, but Piazza’s book often feels schematic, more a showcase for abstract debates than a world of genuine characters.

The heart of Piazza’s book is a showdown between Whitman and Melville about the prospects for America. With “the full-throated bray of a roustabout,” Whitman recites one of his ecstatic catalogs, claiming to be “a Southerner soon as a Northerner, a planter nonchalant and hospitable,” as well as a Yankee. Like Lerner, Piazza is uneasy with this seeming embrace of the slaveholding South.

When Whitman praises America as “the land of the new man, and the new woman,” Melville counters with a passage from his epic poem Clarel, in which he holds up the idea of a “new world” to ridicule. “There has never been, nor will there ever be a ‘new man,’” he concludes, “only new ways of stating the same age-old agonies.” Missing from Whitman’s generic lists of planters and traders, Melville claims, are “complex individuals.” Whitman responds, “I don’t write poems about the end of the human race…. I stand on my own feet! I sing myself!” To which Melville retorts, “You sing nothing else!”

One feels that Piazza’s sympathy is with Melville here, and that his Melville isn’t talking just about the 1880s when he notes the many symptoms of imperfect union, including Black people “re-enslaved despite the promise of emancipation” and factory owners reluctant to pay higher wages. “And then what of the demagogue, waiting to inflame the sense of grievance among these parties?”

With that warning, we have time-traveled to the dystopian age of Trump. And yet Piazza—like Lerner in his evocation of the lights over Brooklyn—ends his book with a glimmer of hope, drawn from the “Gilder” chapter in Moby-Dick, in which Starbuck contemplates the “dreamy quietude” of the gentle waves while dangers lurk in the depths below. “Tell me not of thy teeth-tiered sharks,” Starbuck says, “and thy kidnapping cannibal ways. Let faith oust fact; let fancy oust memory; I look deep down and do believe.” Here is the conclusion of Piazza’s junior lecturer, and presumably Piazza’s conclusion as well: “Surely there was a way forward. Whitman, Twain, Melville, Douglass, Stowe…I have their voices in my ear, and I cannot get rid of them. I still believe in America. God help me—I still believe in America.”

Ultimately, Piazza is asking some of the same kinds of questions as Lerner. Why do we go back to writers like Whitman or Melville or Victor Serge in search of answers to our own puzzling times? “Wozu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit?” as Hölderlin said. What are poets for in destitute times? Both Piazza and Lerner try to speak directly to, and even at times to impersonate, the writers who matter to them. For both of them, Whitman, our national bard, is at times a sounding board, at times a whipping boy, and at times an inspiration.

We live in a time when the nineteenth century is rapidly fading into an oblivion to match what the eighteenth century, with its wigs and hooped petticoats, meant to the generation of Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Langston Hughes. Summoning our classic writers can be refreshing in our own cultural climate, when we often assume that writers of the past have more to learn from us than we from them. “Someone said: ‘The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than they did,’” T.S. Eliot wrote. “Precisely, and they are that which we know.”

-

1

In Specimen Days, Whitman places the Kansas celebration in Topeka, and biographers have perpetuated the error. Whitman did visit Topeka, but the dinner occurred at Bismarck Grove, near Lawrence, where Whitman was staying. See Robert R. Hubach, “Walt Whitman in Kansas,” Kansas Historical Society, Vol. 10, No. 2 (May 1941). ↩

-

2

Ben Lerner, “The Faces of Victor Serge,” The New York Review, January 19, 2023. ↩

-

3

See Robert K. Wallace, Douglass and Melville: Anchored Together in Neighborly Style (Spinner, 2005). Wallace notes that the two writers were both in New Bedford in 1840, a confluence also noted by Piazza, and explores evidence for their “mutual awareness between 1840 and 1855.” ↩