It has been almost one year since Hosni Mubarak gave up power, and in the months since then, the future of a newly democratic Egypt has been uncertain. The political transition all but stalled this past summer, as tensions between Muslims and Copts erupted, street violence flared, and the various post-Mubarak political factions repeatedly disagreed on the form the new Egypt should have. This fall, the military council now ruling the country—the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF)—was itself drawn into violent conflict with protesters, leading to more than forty deaths in a single week. Many wondered, amid all this, if a democratically elected civilian government would ever take office.

In late November, as Egyptians finally went to the polling stations, the direction the country would most likely take was at last becoming clear. If the preliminary results of the parliamentary elections are any indication, most Egyptians want a country governed by the Islamists, whom Mubarak and his allies had aggressively tried to suppress. In the first of a three-stage election process, which began on November 28 and ends on January 10, the Islamist factions emerged with 69.6 percent of the votes. Only nine of Egypt’s twenty-seven governorates voted in the first stage on November 28, and there are several weeks to go until the rest cast their ballots—there are some 52 million registered voters in all—but since many of the remaining electoral districts are ones in which the Islamists are known to have a strong popular following, it seems likely that their lead will be maintained, if not strengthened.

That the country’s first free and fair elections will likely result in a parliament in which the Islamists have a dominant majority is casting doubt on the promise of the democratic state that many who took part in the revolution hoped to achieve. When youth protesters first took to Cairo’s Tahrir Square on January 25, they chanted their desire, among other things, for a state that promised social justice, unity, and equal rights for all. For eighteen days last winter, that model for a new and democratic Egypt seemed plausible; it was being lived in Tahrir. Copts and Muslims, women and men, youth and the elderly, secular and religious protested and prayed together and shared tents and meals. The Copts shielded the Muslims against possible attacks by thugs while they knelt down and prayed, and hundreds of the youth members of the Muslim Brotherhood surrounded the square as guardians for all, searching bags, checking IDs, and trying to ensure that informants or people hoping to disrupt the demonstrations would be swiftly escorted out.

In the aftermath of the first election results, many are wondering if the unity that came to typify the Tahrir protests is now a dream of the past. What is the fate of an Islamist-dominated Egypt? And what does it mean for the country’s liberal minorities—the Coptic Christian community, the moderate Muslim upper class, the remaining handful of Jews, and middle-class Muslims who in spite of their adherence to the rituals of Islam are committed to preserving the cosmopolitan Egypt they grew up in? The concerns of some of these groups are largely about the ways they will live. Will women be prevented from working? Will the veil become compulsory? Will public spaces be segregated to separate men from women? (Such measures are supported by the Salafist Al-Nour Party, which has so far received 18.5 percent of the vote.) For the Copts, who make up some 10 percent of the country’s 82 million people and who have faced increasing persecution since Mubarak stepped down on February 11, whether they will be left to freely practice their faith is an acute and daily concern.

Many people are also worried that tourism and the economy might suffer a ruinous blow if laws are passed to ban bathing suits and alcohol and to cover pharaonic monuments—as several Islamists have proposed in recent months. Although the Muslim Brotherhood in particular has so far expressed its commitment to building a democratic and moderate society, many fear that once the Islamists settle into power, their tune might change.

The likelihood of Egypt transforming from a moderate and open society to one resembling Saudi Arabia or Iran seems highly improbable, at least in the short or medium term. After 498 members of the 508-seat “lower parliament” are finally installed on January 14 (the remaining ten members will be appointed by the SCAF), there will be elections for the parliament’s “upper house.” This will be a consultative council of 270 seats—180 of which will be filled by elections, and 90 by members appointed by the SCAF, a clear sign of the continuing powers of the military. Once that entire structure is in place, the parliament’s immediate task will be to select a committee to draft the long-awaited new constitution.

Advertisement

Since the revolution last winter, the subject of the constitution has proved to be divisive, pitting political factions against one another for eight months. The Islamists, confident of winning the elections, were demanding that the newly elected parliament be granted absolute authority to draft the constitution to its liking. The liberals for their part wanted a supraconstitutional declaration promising respect for religious minorities, as well as the broader vision of a democratic state. To each draft of such a document (proposals were made by both leaders of the Muslim Al-Azhar University and the interim deputy prime minister) the various factions have had objections. On December 7, the SCAF further complicated matters by announcing that it would appoint a council to oversee the drafting of the constitution in order to limit the influence of religious extremism. The de facto military rulers now seem intent on using the rising threat of Islamist rule as their excuse for remaining involved in the country’s affairs, and the future power of the army, which has large economic influence and holdings, remains a central question for Egyptian politics.

Under current rules, for example, the parliament will have limited powers. The military council that is now running the country will continue to have overriding authority, which it has used to curb media freedoms and arbitrarily subject civilians to military trials. It is expected that the parliamentary majority will try to put pressure on the military by passing legislation giving itself the absolute right to appoint a new government and to draft the constitution that will shape the country’s future (already this week the Brotherhood accused the military of trying to undermine the parliament’s authority and said they would boycott the advisory council being formed by them to oversee the drafting of the constitution). With the political balance of the new parliament favoring the Islamists, the liberals worry about the ideological direction Egypt might take. As such concerns have increased, many liberals have slowly shifted away from their previously staunch opposition both to the SCAF and to the remnants of the former regime—the felool.

The largest liberal coalition, El-Kotla or the Egyptian Bloc, includes many former MPs who had strong influence under the Mubarak regime. Liberals now view them as preferable to the Islamists. Members of the Egyptian Bloc are also now advocating the continued involvement of the SCAF in the country’s affairs so that it can guarantee that the basic tenets of the constitution remain untouched—namely, that Egypt remain a democratic, modern state, a commitment the SCAF has repeatedly made.

What will happen, then, when the new parliament begins its first session in March? Most likely we can expect continuing arguments over the extent of the parliament’s authority, the timetable for transition and the handing over of powers from the military, and what the new cabinet should look like. In the debate over the constitution many of the Islamists, in particular those of the Muslim Brotherhood, will probably try to exert influence not through outright demands that it be based on Islamic sharia law—already, Article 2 in the current constitution states that Islam is the religion of the state and the principle source of legislation is Islamic jurisprudence—but rather through a subtle play on words and syllables in the Arabic language that can convey double meanings. They will favor a constitution with provisions that provide leeway for later reinterpretation. There will no doubt be fanatical members of the ultra-orthodox Salafis who push for a constitution that asserts boldly and clearly that Egypt is an Islamic state—indeed, some Salafis are already supporting this—but it is doubtful that they will form an overriding majority.

The transitional parliament could be in power for what might be as little as a one-year term, while a regular term in the previous Egyptian parliament was five years. The two largest political factions in the so-called “lower house”—the Muslim Brotherhood (represented by its political arm, the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP)) and the Salafi Al-Nour Party—are well aware that within that term, their constituents will expect them to deliver on some of their promises. Among the failures of both the SCAF and the various interim cabinets in recent months have been their responses to the demands of the revolutionaries, which have resulted in large-scale protests calling for them to step down. Egyptians will expect that the parliament deliver some tangible and immediate results—a pressure that will be felt by the liberal MPs as well.

The Muslim Brotherhood has decades of organizational and administrative experience. Aside from its expansive nationwide networks, its services to the needy have included selling meat at wholesale prices, offering subsidized school supplies, helping with medical treatment, and providing handouts of fresh produce, sugar, cooking oil, and other items. These activities have won it popular followings. The Brotherhood has also long had leading and instrumental parts in the country’s various professional syndicates and labor unions. The doctors’, lawyers’, and engineers’ syndicates, for example, have historically been dominated and led by Brotherhood members. At the journalists’ syndicate, reporters say that some of the board members affiliated with the Brotherhood have provided the best and most efficient services to the syndicate’s members to date—health care plans, for example.

Advertisement

It is the Brotherhood’s strengths in such different spheres of life—both in municipal welfare and as prominent business owners themselves—that give rise to hopes that it will be a positive force in Egypt. Essam el-Erian, deputy head of the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party and the group’s long-time spokesperson, told me this week: “We are ready for democracy and this parliament will work to rebuild this country for all Egyptians.” The party’s secretary-general, Mohamed el-Beltagy, said something similar, insisting that the parliament, and his party in particular, would serve as “the representative of the people”: “we have to respect one another and defend the rights of all Egyptians—of the entire nation and its people.”

The FJP seems to know that it has little choice but to act in a moderate and strategic manner. Issues of education, the economy, and rising inflation are of critical concern and need to be tackled immediately. In both their pre-election campaign rallies and recent press conferences, the Brotherhood leaders have promoted moderate positions. They have included among their supporters a variety of liberal and secular professionals. At the FJP’s first public rally before the elections in the working-class district of Bulac, a leading member of the liberal Egyptian Bloc coalition was among the invited speakers. It also has women and Copts among its members. Many of the hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood women I have encountered at its events work, and some hold full-time jobs. During the years immediately ahead, there is little reason for the party leaders to radically change their tone.

For Islamist factions, the coming parliamentary term offers an opportunity to widen their support and allay fears of Islamic domination. The FJP will doubtless take advantage of its plurality to show that it does not menace the rights of others. But among the MPs of the Salafi Al-Nour, it seems likely that there will be a divide; many Salafist members of parliament envision an Egypt on the model of Saudi Arabia.

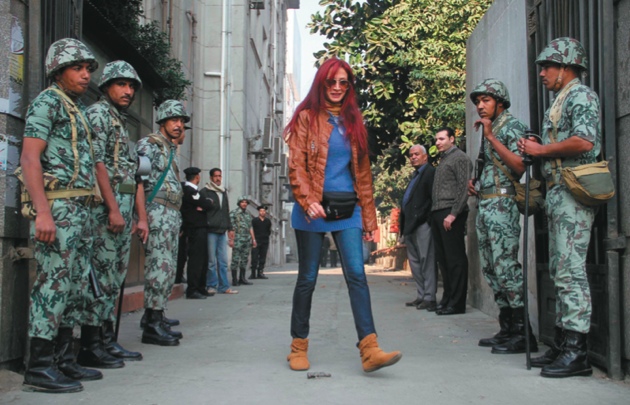

During the next year the laws regarding codes of dress or matters of faith and worship will probably remain unchanged. Transformations are more likely to take place in subtle ways. As the social and cultural landscape of the country is altered, the visibly orthodox Muslims will become freer in their movements. Under the Mubarak regime, the Salafis with their bushy beards and ankle-length galabiyas were very closely watched; many of them were virtually under house arrest. In the months since Mubarak was ousted, and certainly in the center of Cairo, there has been a visible rise in the number of bearded men and of women who are fully veiled. The men, in particular, say that they were persecuted for their beards under Mubarak’s regime, often keeping them trim if they grew them at all. Or as many told me, they simply stayed in their Islamist governorates or city suburbs, where the state’s informants kept them under watch. Now it is probable that the more liberal Muslims, and the country’s Copts, will feel increasingly out of place.

When I went out to vote on the morning of November 28, a topic of discussion as we stood in line for six hours waiting to cast our ballots was what our futures might hold if the Islamists took power. Many women, my mother and her cousins and friends included, shared stories of the past—how they used to take public transportation wearing short skirts or open V-neck tops. “The good old days,” they called them. But many women like my mother, and the others who stood in line in the well-to-do neighborhood of Zamalek, also understand that they are a minority in a country where 40 percent of the population is living on two dollars a day. For many, but certainly not all, such poor people, a sense of security and basic guarantees of survival are paramount. At polling stations in poorer districts of Cairo, like Imbaba, Shubra, and Ain Shams, people told me that they wanted “stability and a strong economy,” and that “ultimately it is in God’s hands.” During the campaign, liberals spoke of a secular state; Islamists, trying to speak for the masses, concentrated on the cost of food. It is on such promises of better conditions that the Islamists will be expected to deliver.

Some of the election results were not unexpected. The Muslim Brotherhood has long been known to be the country’s largest and most organized movement, with widespread networks and growing popular support. As it offered increasing numbers of Egyptians social services where the government had failed, it came to be considered the greatest threat to the Mubarak regime. The deposed leader had often warned that if he left power, the Muslim Brotherhood would rise.

Indeed, in the 2005 parliamentary elections, Muslim Brotherhood members—forced as an outlawed political group to run as independent candidates—won the largest bloc of seats, eighty-eight, in opposition to the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), which won 311 seats. The ballots, moreover, were significantly rigged in the NDP’s favor. What is surprising, then, is not that—with a voter turnout of 52 percent—the Brotherhood won 47.6 percent of the votes in November, and seems likely to win more in the remaining elections. What was unexpected was that the ultra-orthodox Islamist Salafis, newcomers to electoral politics, won 18.5 percent of the votes. (The moderate Islamist Al-Wasat Party took 2.4 percent, and the liberal parties and coalitions collectively just 20.5 percent, 7.1 percent of the vote going to the nationalist liberal Al-Wafd and 10.7 percent to the Egyptian Bloc.)

The success of the Salafis—mainly represented by the Al-Nour Party, which was formed after the revolution—seems partly owing to recent miscalculations of the Brotherhood, which has repeatedly been absent from Friday protests and demonstrations that had the support of most other political groups, even the Salafis. The Brotherhood boycotted the May 27 “Day of Rage,” or “Second Revolution,” angering many of the million people who took part. Over the months, the Brotherhood leaders also changed and changed again their positions on a variety of issues—including the status of Copts and the end goal of an Islamic state—earning them the reputation, as I often heard said, of “never speaking the entire truth.” In conversations with voters in poor neighborhoods during the November 28–29 vote, I frequently heard: “The Brotherhood can’t fully be trusted; they don’t stick to their words. The Salafis are pure.”

Perhaps their biggest mistake came on November 18, when tens of thousands of Egyptians—responding to a call by the Brotherhood—returned to Tahrir Square to protest a government draft document that seemed, among other things, to give the ruling SCAF control over the writing of the new constitution. The demonstration went off peacefully, and when darkness eventually fell, the Brotherhood packed up and left, satisfied with the show of force.

In the early hours of the following morning, riot police stormed the square, forcefully clearing it of the remaining protesters, mainly activists and revolutionary coalitions. In the days that followed, clashes between the police and protesters escalated, with the state’s various security forces unleashing a kind of violence that had rarely been seen since the revolution. Tear gas was fired in toxic amounts, poisoning many and killing some; specially trained forces seemed to be targeting protesters’ eyes. In the course of a single day, five young men lost sight in one eye, and one man—Ahmed Harara—was blinded (he had lost his first eye on January 28).

Egyptians were outraged at the level of violence—forty-two people were killed—and at the SCAF’s refusal to take responsibility, withdraw the state’s security forces, and issue an apology. Many liberal parties suspended their campaigns, and some called for the elections to be postponed. The interim cabinet resigned in response to the violent attacks, and the presidential candidate Mohamed Elbaradei offered to forgo his presidential ambitions and instead serve as temporary prime minister to deal with the crisis. The country’s highest Islamic authority, the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar University, succeeded in brokering a truce on the streets so that elections could go forward.

Throughout it all, the Muslim Brotherhood was conspicuously absent, cau- tious about taking sides. On TV programs and talk shows, the liberal candidates went to great lengths to explain why it was not moral to continue their election campaigns while people were dying in Tahrir. The Brotherhood leaders, for their part, insisted that elections take place soon; they knew they were far ahead of the other parties and coalitions. They had been waiting for this moment for eighty years; they weren’t prepared to let it slip away.

On the night of November 24, members of the Brotherhood reappeared in the square with the intention of clearing it—along with the embattled Mohamed Mahmoud Street—of the remaining protesters. “They did everything they could to get people to go home,” a friend told me. “They would assess the type of person you are, and speak to you in a way that they thought would persuade you. They were willing to go to any lengths to make sure that people left that night.”

It is widely believed that the Brotherhood leaders had made a deal with the SCAF. They would clear the main demonstration site and calm the protesters, and the SCAF in return would hold the elections on time. Many blamed the Brotherhood for how long the clashes lasted and how many lives were lost. In Tahrir on November 25 the Islamist researcher and political analyst Ibrahim El Houdaiby told a group of us: “It would have taken a completely different direction had the Brotherhood come out last weekend and put their weight behind the people.” Even Islamists and some preachers and veiled women spoke of their disappointment with the Brotherhood; they hoped that it wouldn’t win the polls of the following week.

Still, the liberal parties were not able to find much support from the underclass, whether in poor urban districts or rural Egypt. They could not penetrate the decades-old informal networks that have long been dominated by family and tribal alliances, religious affiliations, or agents of the former regime. Even if they had succeeded, the most prominent of the liberal coalitions, the Egyptian Bloc, was headed by the Free Egyptians Party, founded by the telecom tycoon Naguib Sawiris, whose popularity plummeted in June when he tweeted a cartoon of Mickey and Minnie Mouse wearing Muslim gowns and headdresses—Mickey with a bushy beard, and Minnie in a face veil. “Mickey and Minnie after…,” he wrote.

In the weeks following, a full-scale campaign was launched against him by Islamists, urging people to boycott his businesses. In a matter of weeks, 304,000 subscribers left his telecom provider, Mobinil, for local competitors; his company suffered losses of 96 percent for the third quarter of 2011. Even among some liberal Egyptians, Sawiris’s tweet was seen as going too far: “We are a largely Muslim country, Sawiris has to remember and respect that.” In response to the cartoon, a Coptic friend posted on Facebook a message that “the revolution was about unity, not such attacks.”

Amid all this, the Salafi Al-Nour Party has preached in favor of its puritan form of Islam, and a state governed by its principles—one with the same religious restrictions as Saudi Arabia—as the answer to the country’s social and economic woes. The Salafists swiftly followed the lead of the Muslim Brotherhood, providing free and subsidized goods and services to the poor, and focusing their campaign messages on the price of food and cost of living. We don’t know how much the party’s appeal was hurt or enhanced by the fact that its campaign posters didn’t feature pictures of its female candidates, and instead had an image of a rose above their printed names. At a political rally in a public square in Alexandria, it covered a statue of a mermaid with a cloth. But it appealed to Egyptians who spoke the language of the street and believed, among other things, that ultimately, the future of Egypt is in “the hands of Allah.”

In the days since the initial election results were released, the liberals have been discussing how to regroup and prepare for the weeks and voting rounds ahead. Many liberal Muslims and Copts are talking about what the future might hold, including immigration. The Islamist parties, for their part, are anxious not to be grouped together. The FJP has firmly stated that it will not enter an alliance with the Salafis, who themselves have said they will not walk in the shadow of the Brotherhood. (Before the elections, the two groups had agreed on a code of proper behavior during them, but they have not entered into a political alliance.)

In months to come, Egypt’s first freely elected parliament will probably be as fragmented as the political landscape that preceded it. During what will be a period of immense pressure, the Muslim Brotherhood will most likely emerge as a mediator and perhaps the ally of the parliament’s liberal coalition. The military, for its part, will undoubtedly continue to have a hand in the country’s affairs, whether overtly through a provision of the constitution, or through tactical pacts with factions in parliament. Having waited since 1928 for this moment, the Brotherhood can be expected to wait another few years before attempting to make any drastic or fundamental changes in the social and cultural life of the Egyptian state.

—December 15, 2011

This Issue

January 12, 2012

Do the Classics Have a Future?

Convenience

Republicans for Revolution