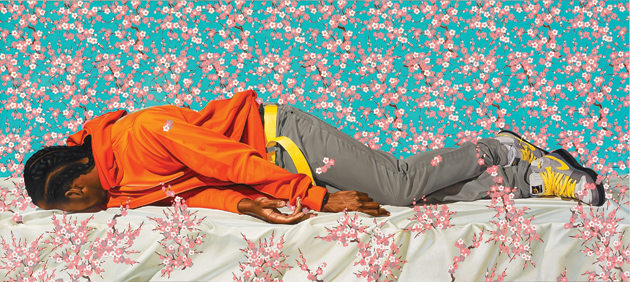

Kehinde Wiley Studio, Inc.

Kehinde Wiley: The Virgin Martyr St. Cecilia, 101.5 x 226.5 inches, 2008; from Kehinde Wiley, a monograph of Wiley’s paintings of contemporary African-Americans in heroic poses, just published by Rizzoli. Two exhibitions of his work are on view in New York City this spring: ‘Kehinde Wiley/The World Stage: Israel,’ at the Jewish Museum, March 9–July 29, 2012; and ‘An Economy of Grace,’ at the Sean Kelly Gallery, May 6–June 16, 2012.

In “Speaking in Tongues,” her stunning essay on Barack Obama and black identity, Zadie Smith remembers how convinced she was when a student at Cambridge by the concept of a unified black voice. Then the idea faded somehow into the injunction to “keep it real,” an instruction she found like being in a prison cell:

It made Blackness a quality each individual black person was constantly in danger of losing. And almost anything could trigger the loss of one’s Blackness: attending certain universities, an impressive variety of jobs, a fondness for opera, a white girlfriend, an interest in golf. And of course, any change in the voice.

It’s absurd, looking back, she says, because black reality has diversified. We’re “black ballet dancers and black truck drivers and black presidents…and we all sing from our own hymn sheet.”1

But recently, when I asked her—in connection with the Trayvon Martin case—if she still felt that way about the hymn sheet, Smith said maybe it wasn’t possible, because there was so much hostility toward black people in the US. In England, she had thought more about class than race. In the US, she discovered that someone else can rush in and define you when you least expect it, making your being black part of an idea of blackness far outside yourself.

An armed Latino’s suspicion that a tall, thin black youth in a hoodie in a gated community at night must be an intruder up to no good closes for me discussion about a post-racial society. Private citizens can now get on a warlike footing with crime, even if the images of the criminal in their heads are racist. Trayvon Martin’s moment of instruction—as Henry Louis Gates Jr. calls the recognition scene when the black youth realizes that he or she is different, and that the white world sees black people as different, no matter how blacks feel inside—has a history, one that yanks everybody back a step.

It would seem that although black people are in the mainstream, black history still isn’t, because certain basic things about the history of being black in America—American history—have to be explained again and again. At the end of the Civil War, vast numbers of black men were on the roads looking for work, for sold-off family, for peace. In the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, black men who could not prove employment or residence in a town that they happened to be passing through were imprisoned and put to work. Vagrancy laws were a form of social control, much like the war on drugs that Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow (2010)—such an important book—forcefully argues is today’s extension of America’s overseer-style management of black men. Drug laws have always been aimed at minorities.

In another brilliant work that tells us how directly the past has formed us, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern America (2010), Khalil Gibran Muhammad looks at the interpretation white social scientists have made of crime statistics since the 1890s that, as he says, stigmatized crime as black and masked white crime as individual failure. Crime was linked to blacks as a racial group, but not to whites. “Blackness was refashioned through crime statistics. It became a more stable racial category in opposition to whiteness through racial criminalization.” Black criminality justified prejudice. Because it was thought that blacks could not be socialized, they were largely excluded from the social reform programs that in the 1920s were making immigrant groups American. Irish, Italian, and Polish immigrants, meanwhile, shed their criminal identities as groups, but blacks didn’t.

Black America has fought back at certain times by embracing stereotypes and turning what have been regarded as cultural defects into cultural virtues. And white America has been riveted. The Jazz Age was, in part, a reaction to the slaughter of World War I. Many whites wanted to be primitive, to be an intuitive, emotional, musical, sexually uninhibited black, as opposed to a mechanistic and rational white. Sherwood Anderson’s Dark Laughter (1926) ends with the black maids laughing at the cuckolded white boss. Similarly, the black urban thug of the 1950s became the existential Beat hero of the nihilistic atomic age celebrated by Norman Mailer in his essay “The White Negro.” The riots of the 1960s politicized the hipster: the street criminal became the political prisoner; the black who would not fight for his country became the black militant with ties to international revolution.

Advertisement

Ironically, the season of extreme black rhetoric in the 1970s coincided with the doubling of the size of the black middle class. New laws mandating equal employment opportunities brought rapid results for blacks. Yet blacks entering the middle class were still disadvantaged compared to middle-class whites. This was why many black critics found unconvincing William Julius Wilson’s thesis in The Declining Significance of Race (1978)—that in the modern industrial system a black person’s economic position shaped his or her life to a greater extent than did race—because it did not adequately address institutional racism, systemic inequality. In the 1970s, most black families needed two incomes to be middle-class. More black women had entered the middle class than black men, because secretarial and clerical work, though considered white-collar jobs, were also thought of as occupations for women. A black man had to have more education and be in a higher occupation in order to earn an income comparable to a white man.

In 1980, the top one hundred black businesses employed no more than nine thousand people. Since Reconstruction blacks had been ruthlessly excluded from mainstream business life. Ida B. Wells, whose Memphis newspaper, Free Speech, had been burned down in 1892, showed that lynching victims were often black men whose businesses whites wanted to take over. Of the 130 black banks founded since Emancipation, one remained by the Depression. During World War II, the largest white insurance company had more black customers than the forty-four black insurance companies combined. White intimidation, the discriminatory practices of white financial institutions as well as the inability to penetrate white markets, would cause most black businesses to fail. Those that survived were what sociologists called “defensive enterprises,” which catered to personal needs—barbers, cleaners, tailors, restaurateurs, grocers—and set up in places where whites didn’t want to operate. The only significant black manufacturers in America were those of skin lighteners, hair straighteners, and coffins.2

Since state and federal government programs were the primary source of middle-class growth for blacks in the 1960s and 1970s, Reagan-era cuts in government spending hit this segment of the black middle class hardest. Blacks made progress in the 1960s because it was the time of “the affluent society.” Blacks were not in direct competition with whites for jobs. However, the recessions of the 1970s and 1980s brought furious opposition among whites to race-biased government policies.

The conservative backlash said that blacks ought to stop blaming white society for the predominance of single-parent households in black America headed by women, the sort of argument that made the social analyses in Andrew Hacker’s Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal (1992) something of a relief. Hacker noted that if a neighborhood became more than 10 percent black, then white flight ensued. Residential segregation determined the quality of the resources black people could get from grammar school to retirement. Many black people greeted former university presidents William G. Bowen and Derek Bok’s The Shape of the River (1998) with elation. Their exhaustive survey of the long-term consequences of affirmative action supported race-sensitive recruitment in higher education, because American society needed black professionals. Moreover, they found that far from being ill equipped to compete in the open market, the beneficiaries of affirmative action were highly successful.

A subgenre of black autobiography emerged that documented the transition from one class to another: these books described the alienation of the black professional in the high-pressure workplace or the loneliness of the black scholarship student at the elite white school, as in Lorene Carey’s Black Ice (1992), a beautiful memoir of her quest for self-acceptance at St. Paul’s, in New Hampshire. In these works, the class voyagers see themselves as the equivalent of being culturally bilingual. Then, too, the debate between separatism and assimilation was going away. To join the system was enough of a challenge to that system. The old war cries that American society had to be remade in order to become equitable faded. Not only was the revolution not going to be televised, it was no longer coming.

Black nationalists in the 1960s and 1970s had been fierce in their judgments of those deemed Uncle Toms, so much so that black neoconservatives still saw themselves as the victims of a totalitarian black identity imposed by black radicals; they, the neoconservatives, were the brave new dissenters, the individualists. The old debate about separatism and integration was transformed into a discussion between pessimists, those who believed blacks would remain outsiders, and optimists/opportunists, those who believed in moving up by working from within. Insiders like Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice supposedly vindicated faith in color-blind success in America. In 2003, Forbes magazine proclaimed Oprah Winfrey the country’s first black woman billionaire. The cultural moment seemed fixated on narratives of ascent. But most of the black middle class was still a lower middle class, living paycheck to paycheck, without substantial assets.

Advertisement

Black colleges had created the old black professional class, a middle class flattered to be seen as an upper class, because truly upper-class blacks, such as Lena Horne’s family, were so few. Traditionally, blacks already someplace tended to resent other blacks trying to crowd in. As St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton reported in Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945), blacks in Chicago who considered themselves “Old Settlers” blamed the devastating white riot against blacks in 1919 on new black arrivals from the South, saying that they destroyed the social balance between the races. Before the mass migration of blacks from the South, the thinking went, there had been plenty of jobs and little prejudice, because blacks had known how to behave. They didn’t “make apes out of themselves,” as one Old Settler civil engineer put it, still annoyed by the no-accounts almost a quarter of a century later.

Drake and Cayton pointed out that membership in the upper- or middle-class Negro world wasn’t determined entirely by income or occupation. Family ties and especially education counted, as did the symbols or markers of middle-class identity: clothes and manners. “Middle-class organizations put the accent on ‘front,’ respectability, civic responsibility of a sort, and conventionalized recreation.” It was the pretensions of the black upper strata that E. Franklin Frazier savaged in his famously ill-tempered essay, Black Bourgeoisie (1957). The black upper class, he reminded everyone, was really only an upper middle class and considerably poorer in relation to the white upper middle class.

Frazier would not have been the only one frustrated by what he saw as the complacence of the black middle class at a critical moment in US history. Because of widespread discrimination in hiring practices, the black middle class hardly increased after the war, though the black GI Bill generation had come of age. It was the America of David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950), his suburbs full of conformists, and Frazier was no less scornful of the materialism on the black side of town. He accused middle-class blacks of not wanting integration because they feared loss of their position. Drake and Cayton had made a similar charge against middle-class blacks in their study, an important work, but of its period, in that “race leader” is identified as a middle-class occupation. The NAACP’s rank and file was drawn from the black professional class, the self-employed who couldn’t be threatened by white bosses, a black middle-class tradition Frazier does not describe.

For Frazier, the black middle class was an escapist elite and never mind that Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King Jr., and Andrew Young grew up in the black middle class or that the elderly black women in the Cottagers, an exclusive Oaks Bluffs club on Martha’s Vineyard, were for the most part staunch supporters of civil rights. All through the 1960s and 1970s, middle-class life in America was mocked. That is an American tradition in itself. Imamu Baraka was stringent in his satire of middle-class blacks, but America went on measuring its social progress in upward mobility, in access to the middle class, and black people kept on wanting to move up.

Interestingly enough, not everyone considered black entry into the middle class the same thing as victory for integration. That was a miscalculation on the part of black neoconservatives, who would be exasperated with Obama because he looked like them on paper but refused to repudiate the lessons of the civil rights era. Black America did not get a conservatism comparable to white political conservatism until the Fairmont Conference in 1980, which brought Clarence Thomas and Thomas Sowell to prominence as critics of civil rights “orthodoxy.” Black neoconservatives received much attention for attacking the prestige of the civil rights movement, but it didn’t work, because ever since the National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, in 1972, convened by Baraka, among others, the benefits of blacks thinking of themselves as a voting bloc, the unified black voice, were obvious in those cities and congressional districts where to do so meant political gain.

Gangster rap and mellower styles of hip-hop have been with us for so long that we can forget the part the rap aesthetic has played in reconciling the black revolutionary imperative with the materialism of American society. The hero of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) says over and over that he is just trying to “get paid,” and hip-hop made “bling” cool not just in the ghetto but in middle-class America as well. Hip-hop crossed racial and class boundaries, its transgressive postures speaking to almost any young man in its orbit. What it told young black men was that success could be a kind of militancy and that it did not mean you had to act white or give up any of your yo dog whassup. Black students took their rap soundtrack with them to Harvard Law School. Blackness was portable. You could take your roots with you, just as Gertrude Stein had hoped.

During the first decade of the twenty-first century one of four black men was or had been in prison, yet blacks were also seen in occupations they hadn’t held before—stockbrokers, corporate attorneys, investment fund managers, CEOs of white companies. Black America was represented at all levels of US society, however thin the numbers at the top. They could object to the assumption that success implied that they were traitors, as the Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy described the anxiety in Sellout: The Politics of Racial Betrayal (2008).

One of the magical elements of President Obama’s rise was that no one had predicted it, in spite of Edward Brooke of Massachusetts and Douglas Wilder of Virginia, who had demonstrated that a culturally assimilated black candidate could appeal to white middle-class voters. Obama’s victory was celebrated in the streets as a promise of American democracy fulfilled, and the triumphalism among the black professional class was astonishing. But this was history, a culmination, a turning point. Everyone could see the painful drama of succession as Reverend Jackson gazed on the president-elect. Since then, a new black elite has been trying to tell us—and themselves—where they stand in relation to black history. There are now so many of them that to be a middle-class black does not seem as elitist as it used to be. The black elite of one generation gets replaced by the black elite of another, the later one defined by different criteria, including a greater sense of freedom.

The black poor are not the ones who are trying to redefine black America. In Distintegration: The Splintering of Black America (2010), Eugene Robinson, a writer for The Washington Post, argues that the pre–civil rights one-nation black America doesn’t exist anymore and that blacks have little in common apart from symbols left over from their civil rights history. Robinson takes it as a given that the blacks of the “mainstream” are now middle class:

Because of desegregation and disintegration, the black middle class is not only bigger and wealthier but also liberated from the separate but unequal nation called black America that existed before the triumph of civil rights. The black Mainstream is now woven into the fabric of America, not just economically but culturally as well.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 2010 that the median income of blacks had fallen from $32,584 to $29,328, compared to the national median income of $49,777. While 43.7 percent of whites were categorized as middle-class, the percentage of the black population that was middle-class was 38.4 percent. Almost 29 percent of the black population was called working-class and 23.5 percent was described as living in poverty.

Robinson renames the black classes: the Emergent, meaning African immigrants who now outperform Asian students at the university level; the Abandoned, or the underclass, as they have been called, blacks trapped by low income in neighborhoods and schools where it is impossible to project a decent future; the Mainstream, who may work in integrated settings but still lead socially all-black lives; and the Transcendent, “a small but growing cohort with the kind of power, wealth, and influence that previous generations of African Americans could never have imagined.”

Robinson hopes that the Transcendent class will provide leaders, much as Du Bois had called on his Talented Tenth over a century ago, but Robinson’s expectations contradict his own evidence that blacks don’t feel race solidarity the way they used to. He cites a 2007 Pew poll that said 61 percent of blacks don’t believe that the black poor and the black middle class share common values.

To judge from Touré’s confident Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness? What It Means to be Black Now, the Transcendent are keen to inform America that what it means to be black has changed for them. Touré, a Rolling Stone and MSNBC contributor, CNN popular culture correspondent, and apostle of the hip-hop aesthetic, contends that there are now as many ways to be black as there are black individuals. Touré was born in 1971. His generation may have missed the heroic civil rights era, but he claims they are at ease in the decentralized world of new media and competitive branding. They are liberated by Obama’s example; “authentic” and “inauthentic” no longer apply:

The definitions and boundaries of Blackness are expanding in forty million directions—or really, into infinity. It does not mean that we are leaving Blackness behind, it means we’re leaving behind the vision of Blackness as something narrowly definable and we’re embracing every conception of Blackness as legitimate. Let me be clear: Post-Black does not mean “post-racial.” Post-racial posits that race does not exist or that we’re somehow beyond race and suggests colorblindness: It’s a bankrupt concept that reflects a naive understanding of race in America. Post-Black means we are like Obama: rooted in but not restricted by Blackness.

Touré interviews 105 black people, mostly men, some older than he, and most from Robinson’s Transcendent sphere: politicians such as former Congressman Harold Ford Jr. of Tennessee; rap stars like Chuck D of Public Enemy; writers, including Greg Tate, Nelson George, and Malcolm Gladwell; academics such as Henry Louis Gates Jr., Cornel West, and Patricia Williams; and artists like Kara Walker, Glenn Ligon, and Kehinde Wiley, among others. The majority of his interviewees are “identity liberals,” legatees of Zora Neale Hurston’s refusal to see her work as being always in the service of mournful racial uplift.

They recall the “nigger wake-up call,” Touré’s sensationalistic term for Gates’s moment of instruction. Several of these stories involve the police. Most have to do with coming up against the matter-of-fact power of whiteness. For example, Derek Conrad Murray, an art history professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, remembers when his father, a hospital administrator, moved the family to an exclusive suburb of Seattle in the early 1980s. His intensely Catholic family was the only black family that attended mass at a large church in the area. One Sunday, a mentally unstable parishioner stood and yelled, “You niggers should get out of here!” Murray said his father chased the man into the street and nearly choked him to death. The shock to the family was such that nobody ever went to church or prayed again. Murray became an atheist.

Touré comments that these stories are not just about whites attempting to break black spirit, they are also about black resiliency. Touré’s subjects sometimes remember a harrowing racial experience and then declare that the lesson they took away was their determination to be as free personally as possible. They claim for themselves the unencumbered psychological freedom that several young black politicians appropriate for themselves in Gwen Ifill’s The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama (2009). Everyone knows that having a black president means something. People are knocking themselves out to explain just what. But it’s too soon.

The black people who seem most free in Touré’s book are the visual artists. Indeed, “post-blackness” was a term coined in the late 1990s by Thelma Golden, director of the Studio Museum of Harlem, and the conceptual artist Glenn Ligon to describe “the liberating value in tossing off the immense burden of race-wide representation, the idea that everything they do must speak to or for or about the entire race.” Black culture is a subject matter, but the new black artists don’t treat it as “specific to them.” It is not autobiographical. It is an interest, not a weapon.

While it is obviously true that Kehinde Wiley, one of the hottest artists in New York, is very different from the black artists Jacob Lawrence or Romare Bearden in his attitude toward his subjects, Wiley still draws on black history, black images. Similarly, Touré’s short stories in The Portable Promised Land (2002) and his novel, Soul City (2004), are allegories written in a black jive that has lost none of its connection to the past and depends on it for meaning. Many critics have made the point that white America has no trouble taking black culture on board while leaving black people out in the cold.

Touré urges black people to claim the freedom of the artist. This message from James Baldwin’s fiction is hardly new. Touré has little to say about the “new Jim Crow” that has put so many poor young blacks in prison. For him, blackness is above all about style. Touré’s interviewees stress the importance of not internalizing society’s messages about blackness, a dictum that goes back to Marcus Garvey. What’s new is not knowing whether racism is behind the hassles that come up in daily life for a black person. Nelson George: “Now, if they show you their ass somehow then you have to decide whether this is racism or it’s because they’re assholes.”

Touré asserts that much of black America did not share white America’s outrage at the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001: “A spoiled country getting the comeuppance it deserved.” Many whites may also have felt this “emotional distance,” just as many blacks were, indeed, grief-stricken. But then Touré moves quickly on to his main point: the end of ambivalence about being American for blacks like him. “We are American. And we are so American that rejecting this country means rejecting part of ourselves.”

Historically, Pan-Africanism has been a component of American black nationalism, but Touré makes it clear that his generation isn’t looking to Africa as their source of black identity, a major generational difference:

Black Americans and Africans are speaking different languages when it comes to race because of histories on different sides of slavery and the Atlantic…. We are, like jazz, rock ’n roll, and hiphop, a child of Africa molded by distinctly American longings, joys, and pains as well as uniquely shaped by being in America.

Touré’s parents grew up under segregation in the projects in Brooklyn, “with laws and society arrayed to attempt to keep them boxed in to niggerdom.” But Touré’s parents reared their family in a middle-class suburb of Boston. Touré went to private school, where he played tennis and was not the only black kid in his classes. “I grew up in an integrated world without racist laws holding me back.” Now Touré lives in a hip, mixed section of Brooklyn, has married outside the faith, as he puts it, and is socially relaxed enough that when his toddler dived into a piece of watermelon he trusted that his white friends were laughing because children do cute things, not because a pickaninny displayed the response to watermelon that they as whites had been conditioned to expect.

Touré represents the anti-essentialist idea of blackness, a discourse of privilege, far from the race feeling that said if it happens to one of us, it happens to all of us. But I remember what it is like, wanting to break away from categories not of your own devising. I told myself that I would not become one of those old heads who says, In my day…. Still, I find myself thinking back to my youth, when not long after King was killed my sister tried to tell me about a cousin of my mother’s who was lynched in 1930. I didn’t want to hear it. I fled. I got away from that contagious form of blackness, the historical truth.

Then a few years later, I read J. Saunders Redding’s On Being Negro in America (1951), a book from Elizabeth Hardwick’s shelves. Redding, by then a prim professor, remembered that when he was at Atlanta University in 1930, he armed himself after a classmate, Dennis Hubert, was lynched because he’d been seen talking to a white girl. The name of my mother’s cousin rushed toward my eyes. I phoned home. My mother had been six years old when it happened. She recalled that her mother was wearing a blue dress. She left the house suddenly….

-

1

Zadie Smith, “Speaking in Tongues,” The New York Review, February 26, 2009, based on a lecture given at the New York Public Library in December 2008, and collected in Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays (Penguin, 2009). ↩

-

2

See Bart Landry’s The New Black Middle Class (University of California Press, 1987). ↩