Manhattan was the capital of the twentieth century and Harlem as the Mecca of the New Negro helped to make it so. In Black Manhattan (1930), James Weldon Johnson, poet and NAACP executive secretary, recounts Negro Harlem’s coming into being as a real estate speculation story. He makes it seem as though Negroes were eager to be bought out and leave the Tenderloin district as plans for Pennsylvania Station at the beginning of the twentieth century assured their displacement. Meanwhile, by 1905 Harlem, with its yacht club and opera house, had been overbuilt. Housing was going unrented, unsold. Negroes, in Johnson’s history, seized the chance to live in new apartment houses and to purchase handsome dwellings. As Negro Harlem spread, German Jews and Anglo-Saxons left: “They felt that Negroes as neighbours not only lowered the values of their property but also lowered their social status.” Negro Harlem spread quickly from its hub along West 135th Street and kept on expanding.

Migration made Harlem. Many “aliens” went back to Europe with the outbreak of World War I, Johnson observes. Most importantly, no immigration meant an interruption in the supply of labor in the North. Manufacturers sent recruitment agents south to persuade Negro workers to move, and they came north in their hundreds of thousands, Johnson says. What he does not say is that they were not only in search of better opportunities, they were also escaping the violence of the South.

Johnson makes distinctions among Negro migrants, arguing that New York got a population better prepared for city life than, say, Chicago did. But the effects of congestion on the existing housing stock, the comparatively low wages and high rents for Harlem’s Negro residents, the general youth of the newcomers—these factors are not a part of the story Johnson tells, still in the flush of the Negro Awakening. For Johnson, the history of the Negro people in New York—the deadly riot against them in 1900, the Silent Parade down Fifth Avenue to protest lynching in 1917—leads to scenes of triumph. Negro soldiers back from the war in 1919 paraded up Fifth Avenue, in the opposite direction of the lynching protest parade. Harlem was not a ghetto in Johnson’s view but a destination, an achievement, a secure, settled Negro area with an established community life.

He is proud of Harlem’s reputation in the 1920s as a place for laughing, singing, and dancing, with “lines of taxicabs and limousines standing under the sparkling lights.” It is famous for its colorful, exotic, sensuous life. “The people who live there are by nature a pleasure-loving people,” strolling, socializing, chattering. Even its dozens and dozens of churches are for dressing up and flirtation. The bourgeoisie and the underworld alike bask in Harlem’s “sense of humour and a love of gaiety.” Black Manhattan is cultural history, not sociology, a celebration of Harlem’s theaters, nightclubs, and low haunts. Johnson is enthusiastic about the cultural progress that Harlem represents: Negro artists as the makers of song and dance; Negro actors finding a place on the legitimate stage and movie screens; Negro musicians heard on the radio and in the “phonograph” industry.

“The most outstanding phase of the development of the Negro in the United States during the past decade has been the recent literary and artistic emergence of the individual creative artist,” Johnson writes, “and New York has been, almost exclusively, the place where that emergence has taken place.” While sacred songs, blues, jazz, and folklore were no longer “racial” but “wholly national,” because they had been so thoroughly absorbed, the rising feeling among Negro artists strikes Johnson as such a departure that it seems “like a sudden awakening, like an instantaneous change.” A new wave of poets and novelists had overthrown the plantation tradition and the stereotypes in subject matter that were also national in character. No more banjos, possums, or watermelon. The rural past had been exchanged for the urban future. “What they did was to attempt to express what the masses of their race were then feeling and thinking and wanting to hear. They attempted to make these masses articulate,” Johnson writes.

Marcus Garvey brought to the US his message of race pride, “Africa for the Africans: At Home and Abroad”; W.E.B. Du Bois poured the scorn of his revisionist insights and original concepts on America’s history; and in the aftermath of World War I the supposed rationalism of Western societies was dismissed as delusional. The overthrow of racial stereotypes involved the appropriation of some of them. Characteristics that had been viewed as evidence of the limitations of Negro culture in America were turned into virtues: the spiritual endowments of the Negro soul. Langston Hughes vowed that his generation would express their dark-skinned selves without apology.

Johnson was older than the Harlem Renaissance writers and artists he welcomed, while elders such as Du Bois and the social historian Benjamin Brawley disapproved of this literature when it seemed to appeal to prurient interest in the low-down aspects of Negro life. However, when it comes to the visual arts, Johnson is reserved, as he also is about the Negro classical composers of his time. He acknowledges that Aaron Douglas of the “Harlem group” has won some recognition for his black-and-white drawings and as a book illustrator. Yet in spite of his “marked originality,” neither Douglas nor the new sculptors at work have, Johnson says, matched the accomplishments of Henry Ossawa Tanner and the Negro artists of the previous generation. Tanner, born before the Civil War, was still alive during the Harlem Renaissance.

Advertisement

Alain Locke, the philosopher sometimes referred to as the godfather of the Harlem Renaissance, edited The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), the anthology of poems, dramas, stories, and essays on Negro heritage, music, and art that was a herald of the new era. The Negro people had broken free and taken possession of their humanity. For Locke, the necessary militancy for self-assertion depended on discovery of the cultural past. While he is confident about music, poetry, and dance, he, like Johnson, is concerned that “there have been notably successful Negro artists, but no development of a school of Negro art.” The individual artist cannot be dictated to, “but from the point of view of our artistic talent in bulk…we ought and must have a school of Negro art, a local and racially representative tradition.”

African art could show that “the Negro is not a cultural foundling without his own inheritance.” The “portraitistic idiom” was not what young Negro artists should learn from; African art, which “is at its best in abstract decorative forms,” must teach them. Locke is thinking primarily of the sculpture that had captured the attention of contemporary European artists. “It is this aspect of the folk tradition, this slumbering gift of the folk temperament that most needs reachievement and re-expression,” even though African art, rigid, controlled, disciplined, and ruled by conventions, was the exact opposite of free and exuberant “Aframerican” art, in his view.1

When Johnson and Locke were writing, the Harlem Renaissance artists had not yet fully emerged. They’d scarcely had the time to. Interestingly enough, Locke changed his mind about the “portraitistic idiom” in the 1930s, when, as the artist and scholar David C. Driskell has informed us, representational art became associated with conservatism, as opposed to the Modernist aesthetic of European art. For Locke, the 1930s were a time when “American art was rediscovering the Negro.” There was a place for Aframerican artists and sympathetic depictions of their people in American Scene art and social realism and in the Public Works of Art Project and the Federal Art Project of the WPA.2

The Harlem Renaissance is supposed to have ended by the time the WPA and other New Deal programs went into effect. The stock market crash of 1929 discouraged thrill seekers from coming uptown, but for Langston Hughes in his first autobiography, The Big Sea (1940), the end of the “gay times of the New Negro era in Harlem” came with the funeral in 1931 of A’Lelia Walker, heiress and hostess, the “joy-goddess” of Harlem. “I had a swell time while it lasted. But I thought it wouldn’t last long…. For how could a large and enthusiastic number of people be crazy about Negroes forever?”

Johnson asked in Black Manhattan how long the Negro would be able to hold on to Harlem. In his autobiography, Along This Way (1933), the tourists may have stopped coming, but Harlem remained the capital of Negro race consciousness. The day Ralph Ellison arrived in New York in 1936 he ran into Hughes. Ellison considered himself a musician but studied sculpture for a short time with Richmond Barthé and stayed with him in Greenwich Village until he could get on his feet. He went back to Harlem and soon met Richard Wright. In 1938 Wright likened Negro writing of the past to servile petitioners. The folklore that addressed the Negro had not yet been caught in paint or stone, he added. Ellison, too, was then in his leftist phase and hurt Hughes’s feelings by criticizing The Big Sea in a review for what he saw as its lack of intellectual range. Their generation was making some of the same bold pronouncements that Hughes’s had.

During the civil rights era, another upsurge in mass consciousness, a new cool generation was promising itself that it would not make the mistakes of its elders. James Baldwin hardly mentioned the Harlem Renaissance in his writing, though Countee Cullen had been his French teacher in junior high school. Harold Cruse, looking back in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967), lamented that apart from Du Bois, who concluded that all art was propaganda, Negro intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance had failed to understand cultural revolution as a political demand. Moreover, they had allowed cultural paternalism, whether in the form of Fifth Avenue philanthropy or Marxist theory, to distract them from the nationalist goals that Cruse argued should be what Negro intellectuals concern themselves with. “After all, who shall describe Beauty?” Du Bois asked.

Advertisement

Who? The artists themselves, replies the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.” The painting and sculpture that Johnson and Locke hoped for and that Wright missed are on abundant, vibrant display, together with several graphic works, a great number of photographs, and a double-sided screen showing dance on film. It can’t be an exhibition dedicated to a school of Negro art, or even a tradition of it, because there isn’t just one. If anything, the exhibition liberates the individual African American artist. It says how eclectic the past is in its artistic practices and styles. It is a history lesson, one that reminds us that we are as far from the beginnings of Modernism as Modernism was from the Romantic era.

Then, too, the protests of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition in response to the 1969 Met exhibition “Harlem on My Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968” had a lasting effect. The exhibition, which included photographs, photomurals, and documentation, seemed unmediated, insufficiently explained. Moreover, it offered no separate work by African American artists. (Blown-up reproductions of Van der Zee and Gordon Parks photographs were incorporated into the wall decoration.) However, exhibitions that followed in the 1970s and 1980s, such as “Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America” at the Studio Museum of Harlem in 1987, were intended to draw attention to African American artists of the past, to give visibility to work that had not been widely viewed. After Paul Gilroy’s cultural study The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (1993), there was more interest in “hybridity” than “ethnic absolutism” as the aesthetic journey of a diasporic people. “Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance,” an exhibition first mounted at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1997, explored the global significance of the visual, literary, and musical works of the period.

“The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” brings a similar but sharper perspective to the participants in the Negro Awakening and their international reach. “The New Negro artistic and literary community, while predominantly African American, was never either exclusively Black or American,” Denise Murrell writes in the fascinating catalog of the show. (As a curator, Murrell contributed to Le Modèle noir de Géricault à Matisse, the catalog of the unforgettable 2019 exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay. She also contributed as the curator to Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, the catalog of an exhibition at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery that same year. That exhibition, unlike the Paris show, focused on the female figure.) In addition to Murrell’s exhaustive introduction, which places the diverse works on view at the Met in a historical setting, the catalog features essays on different and sometimes unexpected aspects of the New Negro movement, such as gambling imagery, Harlem’s relation to the Dutch Caribbean, its influence on artists from the Antilles, the parades, the importance of the gay sensibility to what was then going on, and a survey of past exhibitions about the Harlem Renaissance.

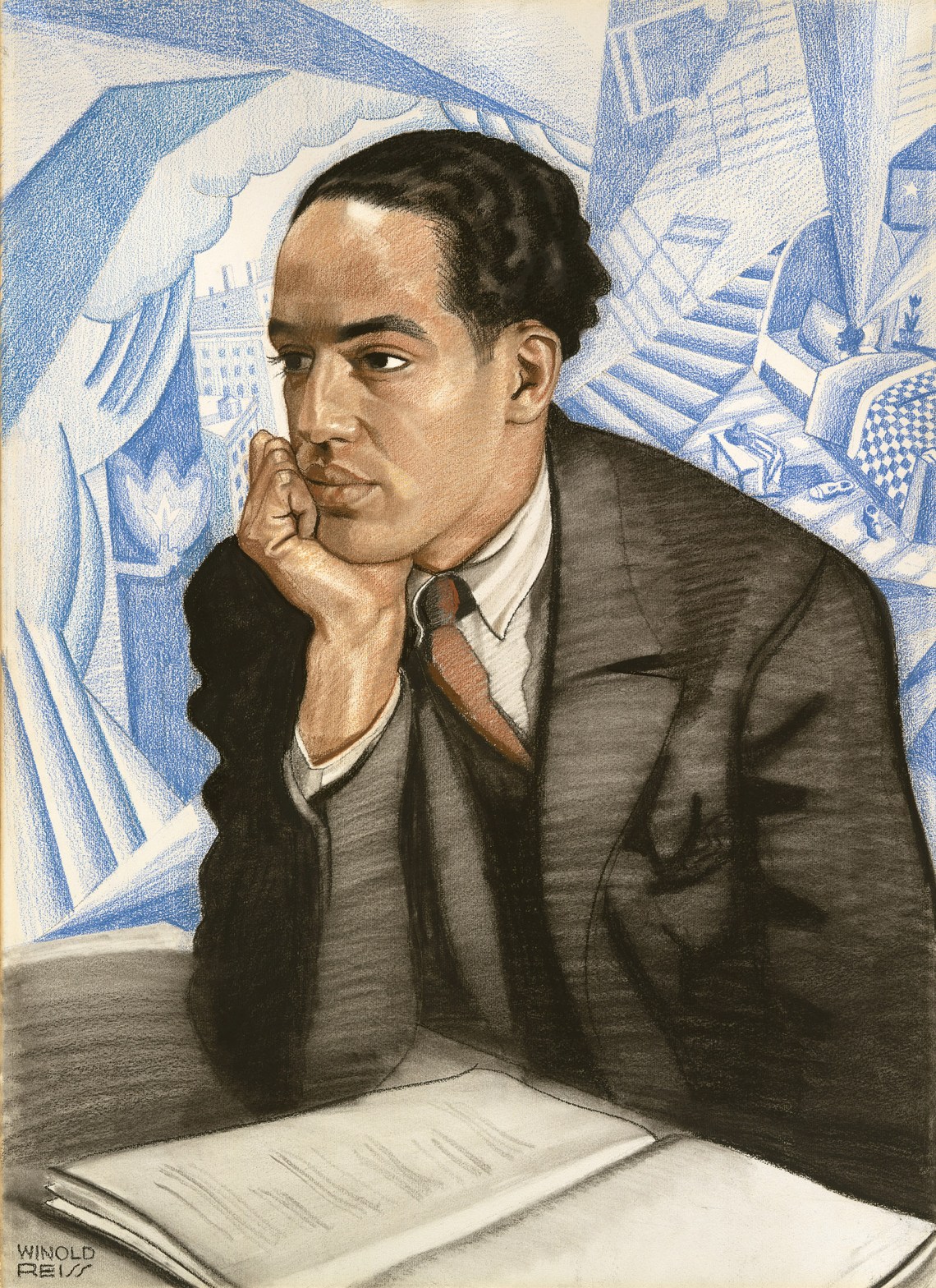

The show opens with portraits of key figures of the period. Among them are the splendid, delicate likenesses of Alain Locke and Langston Hughes done in 1925 by Winold Reiss. (There is also a plaster head of Hughes done by the Cuban artist Teodoro Ramos Blanco sometime in the 1930s.) Given the scope of the exhibition, it isn’t a surprise to come across works on paper by Picasso (Minotaur and Woman, 1937; “Negro, negro, negro…,” Portrait of Aimé Césaire, Laureate, 1949); paintings by Matisse (Aïcha and Lorette, 1917; Dame à la robe blanche, 1946; L’Asie, 1946), along with a drawing (Madagascar, 1943) and an etching (Martiniquaise, 1946); Miguel Covarrubias’s lovely Black Woman Wearing a Blue Hat and Dress (1927); and Jacob Epstein’s 1928 head of Paul Robeson.

The unfamiliar and unknown get to be seen. For instance, the Dutch painter Nola Hatterman’s striking portrait of the handsome sports figure Louis Richard Drenthe from 1930. Kees van Dongen (White Feathers, 1910–1912) is mentioned in The New Negro as one of the European painters influenced by African art. Jan Adriaan Donker Duyvis, born in Indonesia, introduces many viewers to a Surinamese author in his pastel-on-paper portrait of Anton de Kom. In Ballet Dancers in the Attic Rotunda, Paris Opéra (1942), the French artist Yves Brayer captures in broad strokes the fellow feeling of three dancers resting. And how many visitors to the Met will know Edvard Munch’s Abdul Karim with a Green Scarf (1916)? Munch met Karim when he was sketching a traveling circus in Oslo, made several portraits of him, and hired him to be his studio assistant.

Charles Henry Alston’s painting Girl in a Red Dress (1934) has been frequently reproduced. One of the intense pleasures of the exhibition is the sense of meeting works in person, so to speak. Some artists are represented by a single work, and it is unfair to rush through the names: Germaine Casse’s Rade de Pointe à Pitre (1920), Suzanna Ogunjami’s Full-Blown Magnolia (1935), William Artis’s Woman with Kerchief (1939), Ernest Crichlow’s ambiguous painting Anyone’s Date (1940), Margaret Taylor Goss-Burroughs’s lithograph Friends (1942). Maybe this exhibition is trying to give them their due. Elizabeth Catlett’s Head of a Woman (Woman) (1942–1944), executed before she moved to Mexico, suggests the impact of Picasso on her social realism. The number of women artists in the exhibition raises the question of why there is nothing in it by Loïs Mailou Jones, one of the few women, if not the only woman, in past Harlem Renaissance shows.

We know Beauford Delaney through his friendships with Baldwin and Henry Miller. He eschewed rigidity of form, as illustrated in his hallucinatory male nude seated on a bed, Dark Rapture (1941). Richard Bruce Nugent, naughty barefoot boy of the Harlem Renaissance, has made the cut with three drawings, a self-portrait and two from his 1930 Salome series. Four paintings by Malvin Gray Johnson, all dated around 1934, reflect a Cubist influence: Elks Marching, Jenkins Band, Harmony, and one of his best-known works, Self-Portrait. His lover, the muralist Earle Richardson, committed suicide less than a year after Johnson’s untimely death in 1934. The male nude was one of Richmond Barthé’s strongest subjects as a sculptor. His realism concentrates on masculinity as grace of movement in his bronze nudes of the Senegalese dancer Féral Benga (1935) and a Cuban boxer called Chocolate (1942).

Harlem Renaissance artists were for the most part trained, and somehow many of them traveled in order to look at art. The dream of France is most touchingly indicated by Hale Woodruff’s landscape Twilight (circa 1926), done when he was still trying to study in Indianapolis, where he probably had few opportunities to see Impressionist works.

Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, the New Objectivity—African American artists saw a great deal in Europe. But David Driskell said that the work of Aaron Douglas was unrelated to any school and was best characterized as “geometric symbolism.” Albert Barnes had shown Douglas his collection of African art. Douglas’s compositions—The Creation (1935), Noah Built the Ark (1935), Let My People Go (circa 1935–1939), The Judgment Day (1939), Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction (1934), and Building More Stately Mansions (1944)—are “spatially flat,” the human forms rendered as silhouettes, stylized and angular, like jazz itself. He was a star of the Harlem Renaissance and is a climactic moment in the Met exhibition. Driskell regrets that Douglas’s most original work was his murals and illustrations, while his easel paintings, such as his prim Miss Zora Neale Hurston (1926), are mostly in the realistic style. Edwin Harleston painted a portrait of Aaron Douglas in the naturalist style in 1930.

Douglas’s peer Palmer Hayden can be unreliable in his imagery. While in the traditional still life Fétiche et Fleurs (1932) he places a Gabonese Fang head atop a piece of Kuba textile on the table next to flowers, signaling the influence of African art that Locke called for, The Janitor Who Paints (circa 1937) is perhaps misleading in its naiveté. The janitor in profile on the right bent over his work wears a beret, the broom and duster of his day job hang on the wall behind him, and on the brighter left side of the painting is a smiling woman holding a child, maybe his family. However, Mary Schmidt Campbell tells us that “an X-ray scanning of the painting performed by the National Museum of American Art shows quite another point of view of the aspiring janitor.” He is “a grinning monkey with fleshy lips and a head that has been distorted into a bulletlike shape.” Mother and child are minstrel figures, and there is a portrait of Lincoln on the wall. Hayden painted it over in 1939. His mysterious Nous quatre à Paris (circa 1930), showing four men interrupted at cards in a pool hall and looking around suspiciously, troubled some of his peers because their thick lips straddled a line between old caricature and African mask. Hayden conformed to the need for an unconditionally positive outlook in his later work, as in the collage-like Beale Street Blues (1943).

Archibald Motley, also of Douglas’s generation, lived in Chicago, not Harlem. Because there is more of his work in the exhibition, we get a more vivid sense of his development than we do of most of the other artists. We can follow him from the realism of Self-Portrait (1920), Portrait of the Artist’s Father (circa 1922), and Uncle Bob (1928) to the carefully rendered details of costume and skin tone in The Octoroon Girl (1925) and Brown Girl after the Bath (1931). Yet what Motley is best known for are his formally inventive genre scenes: Café, Paris (1929), Jockey Club (1929), Dans la rue (1929), and Blues (1929). Nightlife (1943) shows how crowded his scenes are, how controlled his variations on a single hue, how detailed and seductive to the eye.

The Harlem Renaissance artists understood what Locke meant about the importance of African art. The San Francisco sculptor Sargent Johnson wanted to reveal the beauty of the Negro to the Negro and fashioned copper masks from West African prototypes. The folkloric in the Philadelphia artist Horace Pippin’s The Artist’s Wife (1936) or Self-Portrait II (1944) and in the Harlem-born photographer and painter Roy DeCarava’s Pickets (1946) tends toward the abstract, or is a substitute for it. Jacob Lawrence was still a teenager when he took classes at the Harlem Community Art Center in 1937, whose principal was the artist Augusta Savage. Lawrence’s Pool Parlor (1942) and The Photographer (1942) have that then-new folk element, while Savage’s realistic bronze head, Gamin (1929), and her symbolist ensemble Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp) (1939) could be said to convey the aspirations of Negro youth.

William H. Johnson, also of Douglas’s generation, lived in Europe and North Africa from 1926 until 1938. He moved to Denmark after the war, until madness toward the end of his life sent him to a New York hospital. He transformed his Expressionist technique through the use of unrestricted colors and simplicity of form into a folk art that seemed to grow from African American soil: Man in a Vest (1939–1940), a now famous image, Street Life, Harlem (circa 1939–1940), Jitterbugs II (circa 1941), Jitterbugs V (circa 1941–1942), or Moon Over Harlem (1943–1944), to name a few examples. There was a time when the abstract was seen as an escape from the burdens of social commentary, a choice that would make African American artists as free as any other American artists, but it is noticeable how predominant the representational is throughout the exhibition, how absent the purely abstract. It ends with the Met-owned multipanel The Block (1971) by Romare Bearden, done in different media, which shows a varied, self-contained ghetto street life already receding into the historical. None of Bearden’s earlier work is included. In the 1950s he fell out with the goals of the Harlem Renaissance but later changed his mind.

Three of Winold Reiss’s portraits from the 1920s have to do with education: one is of two public school teachers, the other of a college graduate depicted with two children—the future. And then there is Du Bois himself. Samuel Joseph Brown Jr.’s Smoking My Pipe (1934), Mrs. Simmons (circa 1936), Girl in Blue Dress (1936), and Self-Portrait (circa 1941) speak to a feeling about representing the race as well as the class of the subjects. John N. Robinson’s Mr. and Mrs. Barton (1942) depicts more modest people, but certainly the Jamaican-born sculptor Ronald Moody’s portrait Dr. Harold A. Moody (1946) and Archibald Motley’s Portrait of a Cultured Lady (Edna Powell Gayle) (1948) carry an atmosphere of recognizing Negro achievement.

Laura Wheeler Waring made a portrait of James Weldon Johnson in 1943, five years after his death, which may account for the tiny aspiring figures looking heavenward in the background. She did covers for The Crisis but was eclipsed in memory by Aaron Douglas’s radical cover illustrations in the 1920s. The exhibition includes Waring’s Girl in Pink Dress (circa 1927), Girl with Pomegranate (1940), Girl in Green Cap (1943), and her full-length portrait Marian Anderson (1944), which brings to mind the singer’s humble confession in her autobiography that when on tour she ironed her own gowns. “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” brings Waring the attention she has not enjoyed since her solo exhibition at Howard University in 1948.

The historian Carter G. Woodson in A Century of Negro Migration (1918) noted that the Negro middle class in the South began to flee the violence there in the 1890s, a decade or so before the first mass migrations began. Ida B. Wells had already documented in The Red Record (1895) how terror was used to suppress the nascent southern Negro middle class. The phrase frequently used these days, “the politics of respectability,” fails to take into account that this middle class acted as a vanguard, militantly pursuing what the majority American culture did not want its members to have: the confidence of self-won success. From this perspective, the elements of protest, pride, and defiance in the Victorian-seeming Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s small sculptures In Memory of Mary Turner as a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence (1919) and Maquette for “Ethiopia Awakening” (1921) are fully restored, even if they do not seem as African-inspired as the catalog would have it. She stands between Tanner and the Harlem Renaissance generation.

Civil rights organizations and publications and philanthropic foundations supported African American visual artists before the Harlem Renaissance, but the William E. Harmon Foundation’s annual exhibitions and awards in New York held a special place as a showcase for the talents of New Negro artists. After the foundation discontinued the awards program in 1933, colleges and universities such as Howard, Clark, Talladega, the Hampton Institute, Atlanta University, and the Tuskegee Institute became even more important as repositories for art by African Americans, centers of conservation and preservation.3 (Much has survived in family hands.) This historical responsibility was why people were distressed by the news that financially troubled Fisk University had quietly sold in 2010, along with a Rockwell Kent painting, Florine Stettheimer’s painting of a segregated beach, Asbury Park South (1920).4 It was seen as a violation of the terms of the Alfred Stieglitz collection given by Georgia O’Keeffe. In 2012 Fisk reached an agreement to share the collection with the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Historically Black Colleges and Universities were the only places where the work of certain African American artists could be seen, particularly the murals that were important commissions. No doubt this is why the Met exhibition includes work finished long after the Harlem Renaissance had officially ended. “There is continuity in Negro life,” an older, wiser Ellison said.

Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts found a sad, sad place in her book Harlem Is Nowhere (2011), but as David Adjaye’s new Studio Museum in Harlem nears completion, the real estate market resented and dreaded by the Harlemites whom Rhodes-Pitts interviewed has made Harlem less and less a metaphor, a world within a world, a “metonym of tribalized (read Black) urban space,” as Greg Tate called it.5 Cultural memory has become portable in the meantime. There isn’t a Negro school of art, but the subjects of the exhibition—with the exception of a faceless redhead in Yves Brayer’s trio of ballet dancers and three blonde students among the throng in the devotional painter Allan Rohan Crite’s School’s Out (1936)—are all people of color (as if a person could be discolored, Thoreau said). Color remains a unifying principle, a theme. The photographs in “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” are interspersed between the paintings; they are everywhere, by many, but those by James van der Zee exude the qualities of the secure, settled place of established community life that gave James Weldon Johnson hope. They just glow.

This Issue

May 9, 2024

Tom’s Men

Israel: The Way Out

-

1

See Jeffrey C. Stewart, The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke (Oxford University Press, 2018); Martha Jane Nadell, Enter the New Negroes: Images of Race in American Culture (Harvard University Press, 2004); and George Hutchinson, The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (Harvard University Press, 1995). ↩

-

2

David C. Driskell, Two Centuries of Black American Art (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976). ↩

-

3

See Gary A. Reynolds and Beryl J. Wright, Against the Odds: African American Artists and the Harmon Foundation (Newark Museum, 1989), Richard J. Powell and Jock Reynolds, To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (Studio Museum in Harlem/Addison Gallery/MIT Press, 1999). ↩

-

4

Susan Mulcahy, “A Prized Stettheimer Painting, Sold Under the Radar by a University,” The New York Times, July 26, 2016. ↩

-

5

Thelma Golden, harlemworld: Metropolis as Metaphor (Studio Museum in Harlem, 2004). See also Afro-Atlantic Histories, edited by Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo (DelMonico/Museu de Arte de São Paulo, 2021), and Afro-Modern: Journeys Through the Black Atlantic, edited by Tanya Barson and Peter Gorschlüter (London: Tate Publishing, 2010). ↩