“Does the world ever speak?” My grandson—an impossibly inquisitive four-year-old—once stopped me in my tracks with that. Years later, I still wonder how best to have replied. The world can surely be interpreted. If not, then we would hardly have science, and a large share of poetry would also be in vain. But does the world offer statements to which we should listen? If we paid attention to all that surrounds us, could we learn where to place our trust and how to direct our actions? There was a time, argues Gabriel Pihas, when we believed that we could. We no longer do so now, though, for modernity is a cultural condition in which we humans monopolize the conversation. The gambits all issue from this source we call “imagination.” “Nature”—the great physical out there—at most can merely stonewall our bids to engage.

Pihas grounds this panoramic thesis in a pivotal location. He walks his readers around the city of Rome. He points to some of its outstanding monuments and paintings, traces the thinking behind their production, contrasts them, and proposes that over time a sequence is revealed. But while Pihas—a professor at St. Mary’s College of California and the academic director of the Rome Institute of Liberal Arts—provides a sort of philosophized vade mecum with his Nature and Imagination in Ancient and Early Modern Roman Art, he takes his sightseers on some daunting detours. We tangle with the theology of William of Ockham, the soliloquies of Hamlet, and Pascal’s thoughts about infinity. Here erudite, there trenchant, Pihas puts on a provocative performance, rising above the abject service that Routledge has delivered him. (Copyediting, it appears, is now beyond this firm’s budget.)

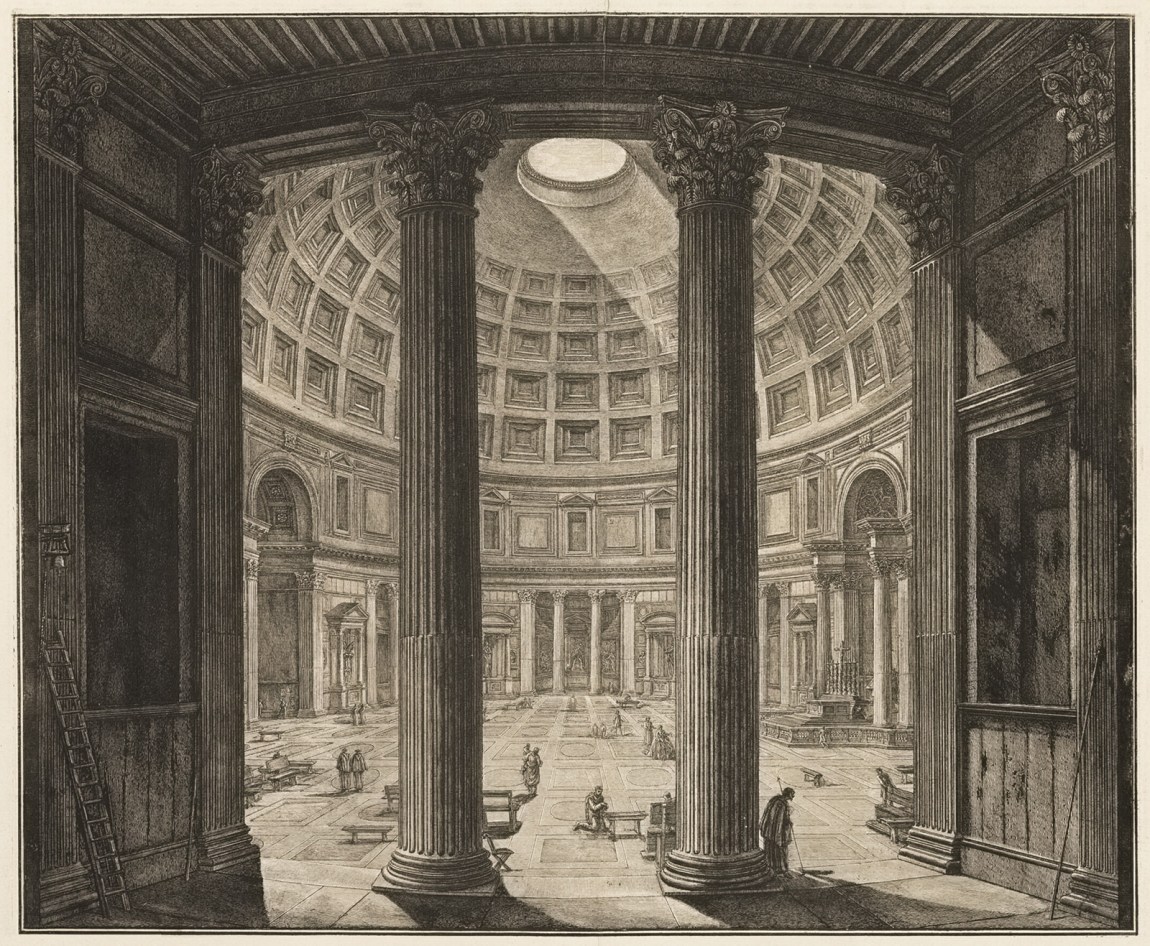

Pihas’s itinerary begins just outside his institute’s doors in central Rome, with a juxtaposition of the Pantheon and the nearby Church of the Gesù. The eight-columned façade of the former and its lofty rotunda, dome, and topmost opening to the skies were erected after Hadrian became emperor in 117 CE, although such a building was first conceived when the imperial system entrenched itself more than a century before. This central temple could affirm the ruler’s authority because it invited down, by way of the oculus, direct, unmediated sunlight into a ritual enclosure in which he might be seated. Descending through a ceiling studded with gilded stars, the shining shaft would confer on him the blessing of the “cosmos”—that term, for Pihas, being crucial. The ancient Greeks and Romans, he explains, used it to point not as we do now to a dizzying vastness, but rather to a harmony underpinning everything above and below us, an order that was in itself divine and moreover within the reach of our understanding.

The entire temple was its representation, the floating hemispherical heaven of the dome complementing the rectilinear earthliness of the portico, with its emphatically physical, load-bearing columns. Thus the world was lent a voice with which to say yes to a pagan regime. That Christians subsequently co-opted the building for their own forms of worship is testimony to the strong retentive sway of that sense of concord. Examining the vegetal and pastoral symbolisms of Rome’s older churches, Pihas argues that nature—humanity’s encompassing environment—would remain for over a millennium God’s chief display board, for all that Jesus had insisted he was “not of the world.”

Walk a few blocks from the Pantheon, however, to enter the Jesuits’ mother church and, looking up, you face an alternate vision of heaven. The illusionistic paintings completed by Giovanni Battista Gaulli on the ceiling of the Gesù in the 1680s appear to blast through its solid architecture, revealing a radiant realm of cloud-surfing seraphim and saints to whom the physical force of gravity no longer applies. The frescoes present light streaming down not from the sun but from a central cross surmounting the letters IHS, a trigraph signifying the savior. For this temple’s purposes, the divine has become at once too dazzling and too abstract to be embodied in natural phenomena. And its proclamation of the power of God, and of a religious order appointed to serve him, is equally a brandishing of the power of fiction. Pihas gasps at the sleight of hand with which “the painted name of Jesus” is seen to generate a “painted light” casting a “painted shadow on the ceiling where the light is obstructed by the painted clouds!”

Gaulli was a disciple-cum-associate of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, which leads Pihas to consider that artist’s multimedia transformations of other seventeenth-century Roman church interiors. Their common purpose, he argues, was to demonstrate “art’s independence from material reality.” Bernini’s seductive showmanship saluted a deity who was truly “not of the world,” and in this purpose, if in little else, it converged with the radically abstract architecture of his rival Francesco Borromini. For the latter, with his reeling, swooping form-language, intended to instill “a restless aspiration of eye and imagination” that swept the ground away from under the worshiper’s feet. A destabilization of this sort (here Pascal’s terror at the “silence of these infinite spaces” is also instanced) could jolt the seventeenth-century mind into confronting an invisible, supernatural transcendence.

Advertisement

As for palpable nature—a system deemed by the era’s incoming physics to operate mechanically—that was now to be treated as a resource for human use. It was without intention. In a coda to his argument, Pihas notes how Piranesi and Hubert Robert interpreted the city of Rome itself as an instance of this incoherence: a giddy jumble of vainglorious projects and weed-strewn ruins, an effective renaturing of all cultural endeavor. By the eighteenth century the intelligible cosmic order on which the ancients set their sights had been utterly upturned.

This book, then, advances a revolutionary mode of art history. We are not as we once were: that is this mode’s first instinct. Looking at the sequence of artifacts, we recognize that in the culture at large, there has been a lurch—a fall, perhaps amounting to a trauma, or alternately an ascent, an upward gearchange. We are deaf to the harmonies to which ancient emperor-worshipers were once attuned; by the same token, we have lost their political blinders. Pihas feels it only proper to keep the seesaw swinging, noting that the latter-day “alienation” from nature might also have “liberating” aspects, yet his closing lines are downbeat. His sightseer is “left somewhat lonely among Rome’s disordered heaps.”

The before-and-after thesis compressed into this walking tour has elsewhere been expanded. Thus at one point Pihas compares the Pantheon’s heaven-and-earth symbolism to that of a cong, an ancient Chinese ritual vessel that likewise combined the circular with the rectangular. David Summers enfolded such comparisons within a global study of cultural practices in his treatise Real Spaces: World Art History and the Rise of Western Modernism (2003). Placement had been paramount, Summers argued, when premodern agents made art. Ancient cultures, with their emphases on orientation, omen-reading, and the study of the stars submitted themselves to a located and concrete “world at hand.” It was only in the Europe of recent centuries that a decentered and infinite space was conceived, opening up the virtual realms in which we nowadays drift.

The antecedent to both Summers and Pihas is Hegel with his Lectures on the Philosophy of Art (1823), a take on the trajectory of humanity in which Geist—“spirit” or “mind”—plays a part similar to “imagination” in the present text, eventually shaking itself free from the materiality to which at first it was bound. All three writers identify the art of painting as that revolution’s catalyst. Summarizing Hegel, Pihas argues that from the Renaissance onward painting urged us to become “lost in the fiction of three-dimensional space on a flat picture plane” and to “transform the world outside us into our projection.” The leading agitator was Michelangelo, with his frescoes that paradoxically thrust forth lunging bodies within the Sistine Chapel’s concave bays, figures with amplified musculatures meant to flaunt “human autonomy and its departure from mere nature.” The chapel is in effect Pihas’s Bastille. History turned its corner right here. Now, tourist, you see why to understand it you had to come to Rome.

Hegel’s story about Geist is hard to shake off: Pihas keeps looking back that way. Yet two centuries later, he navigates an altered sea of time. In the philosopher’s Berlin lectures, history’s current appears unidirectional and inexorable, flowing ever toward spiritualization. In 2023 we allow a little more for squalls and crosswinds—for contingency, in other words. Pihas’s tracing of zigzag threads of causation convolutes his tale but makes it more piquant. One of his more unexpected moves is to relate the mindset behind Michelangelo’s frescoes of the creation to the “voluntarism” expounded by schoolmen such as Ockham in the early 1300s. God’s power to do whatever he wills, this doctrine proposed, must precede the specific creative acts on which he has chosen to embark. Thus he could have made another world than this, and thus the physical conditions in which we find ourselves lack the necessity that is the mark of the divine. This hairline crack in a medieval cloister will develop, in Pihas’s vision, into the major severance from nature that concerns him.

This is not a deterministic narrative, Pihas insists, for such dislocations could arise at other moments. In another wriggling detour he identifies one such juncture occurring when the practice of sculpture in ancient Greece slid from its Classical into its Hellenistic phase, forsaking the assumption that figures were defined by their actions in the world (“We are what we do”) for images of stalled self-consciousness—individuals asking “How can I play my due role?,” the question that troubled Hamlet.

Advertisement

Pihas may not be a determinist, but he is incipiently a moralist. Developing this analysis, he issues strictures on the “inauthenticity” and “tackiness” that lie in wait once art is divorced from nature. It is surely in keeping with this that his tour of Rome’s sights turns its back on the Vittorio Emanuele monument, that grandiose wedding cake set down at the city’s heart to celebrate Italy’s nineteenth-century reunification. Nor does it focus on anything more recent. Having defined modernity by its exclusive reliance on the imagination, Pihas can yet berate it as an “unimaginative age.”

How should we judge these judgments? Those of us who make things may have mixed feelings about revolution-hinged art history. The past is all to some extent strange, but ought that strangeness be partitioned into a before and an after? The past—any past—might also become kin to us, if we could get close enough to the onetime acts of making, whether these be the frescoes of Gaulli or Paleolithic cave paintings. Faithfulness and justice to those fellow makers might be better served by a straightforward chronicle: This person made this, that person made that, and thus things went on. How much drearier, however, that would be to read!