The depression we’re in is essentially gratuitous: we don’t need to be suffering so much pain and destroying so many lives. We could end it both more easily and more quickly than anyone imagines—anyone, that is, except those who have actually studied the economics of depressed economies and the historical evidence on how policies work in such economies.

The truth is that recovery would be almost ridiculously easy to achieve: all we need is to reverse the austerity policies of the past couple of years and temporarily boost spending. Never mind all the talk of how we have a long-run problem that can’t have a short-run solution—this may sound sophisticated, but it isn’t. With a boost in spending, we could be back to more or less full employment faster than anyone imagines.

But don’t we have to worry about long-run budget deficits? Keynes wrote that “the boom, not the slump, is the time for austerity.” Now, as I argue in my forthcoming book*—and show later in the data discussed in this article—is the time for the government to spend more until the private sector is ready to carry the economy forward again. At that point, the US would be in a far better position to deal with deficits, entitlements, and the costs of financing them.

Meanwhile, the strong measures that would all go a long way toward lifting us out of this depression should include, among other policies, increased federal aid to state and local governments, which would restore the jobs of many public employees; a more aggressive approach by the Federal Reserve to quantitative easing (that is, purchasing bonds in an attempt to reduce long-term interest rates); and less timid efforts by the Obama administration to reduce homeowner debt.

But some readers will wonder, isn’t a recovery program along the lines I’ve described just out of the question as a political matter? And isn’t advocating such a program a waste of time? My answers to these two questions are: not necessarily, and definitely not. The chances of a real turn in policy, away from the austerity mania of the last few years and toward a renewed focus on job creation, are much better than conventional wisdom would have you believe. And recent experience also teaches us a crucial political lesson: it’s much better to stand up for what you believe, to make the case for what really should be done, than to try to seem moderate and reasonable by essentially accepting your opponents’ arguments. Compromise, if you must, on the policy—but never on the truth.

Let me start by talking about the possibility of a decisive change in policy direction.

Nothing Succeeds Like Success

Pundits are always making confident statements about what the American electorate wants and believes, and such presumed public views are often used to wave away any suggestion of major policy changes, at least from the left. America is a “center-right country,” we’re told, and that rules out any major initia- tives involving new government spending.

And to be fair, there are lines, both to the left and to the right, that policy probably can’t cross without inviting electoral disaster. George W. Bush discovered that when he tried to privatize Social Security after the 2004 election: the public hated the idea, and his attempted juggernaut on the issue quickly stalled. A comparably liberal-leaning proposal—say, a plan to introduce true “socialized medicine,” making the whole health care system a government program like the Veterans Health Administration—would presumably meet the same fate. But when it comes to the kind of policy measures I have advocated—measures that would mainly try to boost the economy rather than try to transform it—public opinion is surely less coherent and less decisive than everyday commentary would have you believe.

Pundits and, I’m sorry to say, White House political operatives like to tell elaborate tales about what is supposedly going on in voters’ minds. Back in 2011 The Washington Post’s Greg Sargent summarized the arguments Obama aides were using to justify a focus on spending cuts rather than job creation:

A big deal would reassure independents who fear the country is out of control; position Obama as the adult who made Washington work again; allow the President to tell Dems he put entitlements on sounder financial footing; and clear the decks to enact other priorities later.

Any political scientist who has actually studied electoral behavior will scoff at the idea that voters engage in anything like this sort of complicated reasoning. And political scientists in general have scorn for what Slate’s Matthew Yglesias calls the pundit’s fallacy, the belief on the part of all too many political commentators that their pet issues are, miraculously, the very same issues that matter most to the electorate.

Advertisement

Most real voters are busy with their jobs, their children, and their lives in general. They have neither the time nor the inclination to study policy issues closely, let alone engage in opinion-page-style parsing of political nuances. What they notice, and vote on, is whether the economy is getting better or worse; statistical analyses say that the rate of economic growth in the three quarters or so before the election is by far the most important determinant of electoral outcomes.

What this says—a lesson that the Obama team unfortunately failed to learn until very late in the game—is that the economic strategy that works best politically isn’t the strategy that finds approval with focus groups, let alone with the editorial page of The Washington Post; it’s the strategy that actually delivers results. Whoever is sitting in the White House next year will best serve his own political interests by doing the right thing from an economic point of view, which means doing whatever it takes to end the depression we’re in. If expansionary fiscal and monetary policies coupled with debt relief are the way to get this economy moving, then those policies will be politically smart as well as in the national interest.

But is there any chance of actually getting them enacted as legislation?

Political Possibilities

It’s not at all clear what the political landscape will look like after the election. But there do seem to be three main possibilities: President Obama is reelected and Democrats also regain control of Congress; Mitt Romney wins the presidential election and Republicans add a Senate majority to their control of the House; the president is reelected but faces at least one hostile house of Congress. What can be done in each of these cases?

The first case—Obama triumphant—obviously makes it easiest to imagine America doing what it takes to restore full employment. In effect, the Obama administration would get an opportunity at a do-over, taking the strong steps it failed to take in 2009. Since Obama is unlikely to have a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, taking these strong steps would require making use of reconciliation, the procedure that the Democrats used to pass health care reform and that Bush used to pass both of his tax cuts. So be it. If nervous advisers warn about the political fallout, Obama should remember the hard-learned lesson of his first term: the best economic strategy from a political point of view is the one that delivers tangible progress.

A Romney victory would naturally create a very different situation; if Romney adhered to Republican orthodoxy, he would of course reject any government action along the lines I’ve advocated. It’s not clear, however, whether Romney believes any of the things he is currently saying. His two chief economic advisers, Harvard’s N. Gregory Mankiw and Columbia’s Glenn Hubbard, are committed Republicans but also quite Keynesian in their views about macroeconomics. Indeed, early in the crisis Mankiw argued for a sharp rise in the Fed’s target for inflation, a proposal that was and is anathema to most of his party. His proposal caused the predictable uproar, and he went silent on the issue. But we can at least hope that Romney’s inner circle holds views that are much more realistic than anything the candidate says in his speeches, and that once in office he would rip off his mask, revealing his true pragmatic, Keynesian nature.

Of course, a great nation should not have to depend on the hope that a politician is in fact a complete fraud who doesn’t believe any of the things he claims to believe. And such a hope is certainly not a reason to vote for that politician. Still, making the case for job creation may not be a wasted effort, even if Republicans take it all this November.

Finally, what about the fairly likely case in which Obama is returned to office but a Democratic Congress is not? What should Obama do, and what are the prospects for action? My answer is that the president, other Democrats, and every Keynesian-minded economist with a public profile should make the case for job creation forcefully and often, and keep pressure on those in Congress who are blocking job-creation efforts.

This is not the way the Obama administration operated for its first two and a half years. We now have a number of reports on the internal decision-making processes of the administration from 2009 to 2011, and they all suggest that the president’s political advisers urged him never to ask for things he might not get, on the grounds that it might make him look weak. Moreover, economic advisers like Christina Romer who urged more spending on job creation were overruled on the grounds that the public didn’t believe in such measures and was worried about the deficit.

Advertisement

The result of this caution was, however, that as even the president bought into deficit obsession and calls for austerity, the whole national discourse shifted away from job creation. Meanwhile, the economy remained weak—and the public had no reason not to blame the president, since he wasn’t staking out a position clearly different from that of the GOP.

In September 2011 the White House finally changed tack, offering a job-creation proposal that fell far short of what was needed, but was nonetheless much bigger than expected. There was no chance that the plan would actually pass the Republican-led House of Representatives, and Noam Scheiber of The New Republic tells us that White House political operatives “began to worry that the size of the package would be a liability and urged the wonks to scale it back.” This time, however, Obama sided with the economists—and in the process proved that the political operatives didn’t know their own business. Public reaction was generally favorable, while Republicans were put on the spot for their obstruction.

And early this year, with the debate having shifted perceptibly toward a renewed focus on jobs, Republicans were on the defensive. As a result, the Obama administration was able to get a significant fraction of what it wanted—an extension of the payroll tax credit, not an ideal stimulus but nonetheless a measure that puts cash in workers’ pockets, and maintenance for a shorter period of extended unemployment benefits—without making any major concessions.

In short, the experience of Obama’s first term suggests that not talking about jobs simply because you don’t think you can pass job-creation legislation doesn’t work even as a political strategy. On the other hand, hammering on the need for job creation can be good politics, and it can put enough pressure on the other side to bring about better policy too.

Or to put it more simply, there is no reason not to tell the truth about this depression.

A Moral Imperative

It has been more than four years since the US economy first entered recession—and although the recession may have ended, the depression has not. Unemployment may be trending down a bit in the United States (though it’s rising in Europe), but it remains at levels that would have been inconceivable not long ago—and are unconscionable now. Tens of millions of our fellow citizens are suffering vast hardship, the future prospects of today’s young people are being eroded with each passing month—and all of it is unnecessary.

For the fact is that we have both the knowledge and the tools to get out of this depression. Indeed, by applying time-honored economic principles whose validity has only been reinforced by recent events, we could be back to more or less full employment very fast, probably in less than two years. All that is blocking recovery is a lack of intellectual clarity and political will.

But one question remains. I have argued that in a deeply depressed economy, in which the interest rates that the monetary authorities can control are near zero, we need more, not less, government spending. A burst of federal spending is what ended the Great Depression, and we desperately need something similar today.

Yet how do we know that more government spending would actually promote growth and employment? After all, many politicians fiercely reject that idea, insisting that the government can’t create jobs; some economists are willing to say the same thing. So is it just a question of going with the people who seem to be part of your political tribe?

Well, it shouldn’t be. Tribal allegiance should have no more to do with your views about macroeconomics than with your views on, say, the theory of evolution or climate change. The question of how the economy works should be settled on the basis of evidence, not prejudice. And one of the few benefits of this depression has been a surge in evidence-based economic research into the effects of changes in government spending. What does that evidence say?

Before I can answer that question, I have to talk briefly about the pitfalls one needs to avoid.

The Trouble with Correlation

You might think that the way to assess the effects of government spending on the economy is simply to look at the correlation between spending levels and other things like growth and employment. The truth is that even people who should know better sometimes fall into the trap of equating correlation with causation. But let me try to disabuse you of the notion that this is a useful procedure by talking about a related question: the effects of tax rates on economic performance.

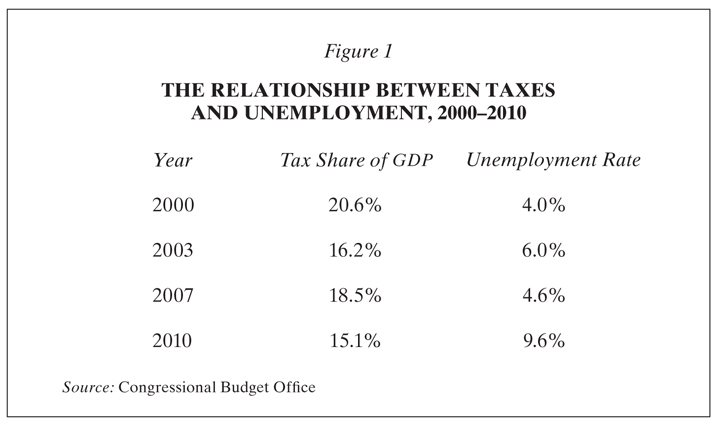

It’s an article of faith on the American right that low taxes are the key to economic success. But suppose we look at the relationship between taxes—specifically, the share of GDP collected in federal taxes—and unemployment over the past dozen years. What we find is that years with high tax shares were years of low unemployment, and vice versa (see Figure 1). Clearly, isn’t the way to reduce unemployment to raise taxes?

Even those of us who very much disagree with tax-cut mania don’t believe this. Why not? Because we’re surely looking at spurious correlation here. For example, unemployment was relatively low in 2007 because the economy was still buoyed by the housing boom—and the combination of a strong economy and large capital gains boosted federal revenues, making taxes look high. By 2010 the boom had gone bust, taking both the economy and tax receipts with it. Measured tax levels were a consequence of other things, not an independent variable driving the economy.

Similar problems bedevil any attempt to use historical correlations to assess the effects of government spending. If economics were a laboratory science, we could solve the problem by performing controlled experiments. But it isn’t. Econometrics—a specialized branch of statistics that’s supposed to help deal with such situations—offers a variety of techniques for “identifying” actual causal relationships. The truth, however, is that even economists are rarely persuaded by fancy econometric analyses, especially when the issue at hand is so politically charged. What, then, can be done?

The answer in much recent work has been to look for “natural experiments”—situations in which we can be pretty sure that changes in government spending are neither responding to economic developments nor being driven by forces that are also moving the economy through other channels. Where do such natural experiments come from? Sadly, they mainly come from disasters—wars or the threat of wars, and fiscal crises that force governments to slash spending regardless of the state of the economy.

Disasters, Guns, and Money

As I wrote, since the crisis began there has been a boom in research into the effects of fiscal policy on output and employment. This body of research is growing fast, and much of it is too technical to be summarized in this article. But here are a few highlights.

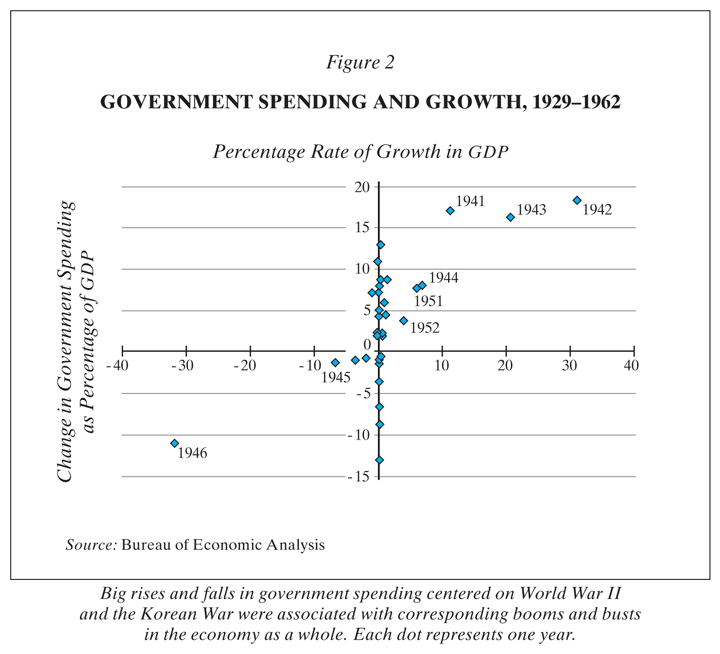

First, Stanford’s Robert Hall has looked at the effects of large changes in US government purchases—which is all about wars, specifically World War II and the Korean War. Figure 2 on this page compares changes in US military spending with changes in real GDP—both measured as a percentage of the preceding year’s GDP—over the period from 1929 to 1962 (there’s not much action after that). Each dot represents one year; I’ve labeled the points corresponding to the big buildup during World War II and the big demobilization just afterward. Obviously, there were big moves in years when nothing much was happening to military spending, notably the slump from 1929 to 1933 and the recovery from 1933 to 1936. But every year in which there was a big spending increase was also a year of strong growth, and the reduction in military spending after World War II was a year of sharp output decline.

This clearly suggests that increasing government spending does indeed create growth and hence jobs. The next question is, how much bang is there per buck? The data on US military spending are slightly disappointing in that respect, suggesting that a dollar of spending actually generates only about fifty cents of growth. But if you know anything about wartime history, you realize that this may not be a good guide to what would happen if we increased spending now. After all, during World War II private-sector spending was deliberately suppressed by rationing and restrictions on private construction; during the Korean War, the government tried to avoid inflationary pressures by sharply raising taxes. So it’s likely that an increase in spending now would yield bigger gains.

How much bigger? To answer that question, it would be helpful to find natural experiments telling us about the effects of government spending under conditions more like those we face today. Unfortunately, there aren’t any such experiments as good and clear-cut as World War II. Still, there are some useful ways to get at the issue.

One is to go deeper into the past. As the economic historians Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke point out, during the 1930s European nations entered, one by one, into an arms race, under conditions of high unemployment and near-zero interest rates resembling those prevailing now. In work with their students, they have used the admittedly scrappy data from that era to estimate the impact that spending changes driven by that arms race had on output, and have come up with a much bigger bang for the buck (or, more accurately, the lira, mark, franc, and so on).

Another option is to compare regions within the United States. Emi Nakamura and Jon Steinsson of Columbia University point out that some US states have long had much bigger defense industries than others—for example, California has had a large concentration of defense contractors, whereas Illinois has not. Meanwhile, defense spending at the national level has fluctuated a lot, rising sharply under Reagan, then falling after the end of the cold war. At the national level, the effects of these changes are obscured by other factors, especially monetary policy: the Fed raised rates sharply in the early 1980s, just as the Reagan buildup was occurring, and cut them sharply in the early 1990s. But you can still get a good sense of the impact of government spending by looking at the differential effect across states; Nakamura and Steinsson estimate, on the basis of this differential, that a dollar of spending actually raises output by around $1.50.

So looking at the effects of wars—including the arms races that precede wars and the military downsizing that follows them—tells us a great deal about the effects of government spending. But are wars the only way to get at this question?

When it comes to big increases in government spending, the answer, unfortunately, is yes. Big spending programs rarely happen except in response to war or the threat thereof. However, big spending cuts sometimes happen for a different reason: because national policymakers are worried about large budget deficits and/or debts, and slash spending in an attempt to get their finances under control. So austerity, as well as war, gives us information on the effects of fiscal policy.

It’s important, by the way, to look at the policy changes, not just at actual spending. Like taxes, spending in modern economies varies with the state of the economy, in ways that can produce spurious correlations; for example, US spending on unemployment benefits has soared in recent years, even as the economy weakened, but the causation runs from unemployment to spending rather than the other way around. Assessing the effects of austerity therefore requires painstaking examination of the actual legislation used to implement that austerity.

Fortunately, researchers at the International Monetary Fund have done the legwork, identifying no fewer than 173 cases of fiscal austerity in advanced countries over the period between 1978 and 2009. And what they found was that austerity policies were followed by economic contraction and higher unemployment.

There’s much, much more evidence, but I hope this brief overview gives a sense of what we know and how we know it. I hope in particular that when you read me or Joseph Stiglitz or Christina Romer saying that cutting spending in the face of this depression will make it worse, and that temporary increases in spending could help us recover, you won’t think, “Well, that’s just his/her opinion.” As Romer asserted in a recent speech about research into fiscal policy:

The evidence is stronger than it has ever been that fiscal policy matters—that fiscal stimulus helps the economy add jobs, and that reducing the budget deficit lowers growth at least in the near term. And yet, this evidence does not seem to be getting through to the legislative process.

That’s what we need to change.

This Issue

May 24, 2012

‘Brimming with Sheer Cheek’

The Rapture of the Silents

-

*

End This Depression Now! (Norton, 2012). ↩