It’s a funny place, Jeddah. Nobody knows the half of what goes on.

—Hilary Mantel, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street

1.

On September 25, 2011, the aging ruler of Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah, gave a remarkable speech to the Majlis al-Shura, the formal advisory body to the Saudi monarchy in Riyadh. Beginning in 2013, the king said, women would be allowed to serve on the 150- member body; and beginning in 2015, they would also be permitted to vote and run for office in municipal council elections.

To most outside observers, these moves were hardly worth noting. In 2011, popular revolts were toppling autocratic regimes across the Middle East; even fellow monarchies like Morocco and Jordan were amending or changing their constitutions to show they would be more accountable to the people. By contrast, the Saudi king’s speech conceded no new authority to the Majlis al-Shura, an unelected body with limited powers of consultation only, and Saudis have shown little interest in the largely symbolic local councils, only half of whose members are elected. Moreover, Abdullah’s innovations, such as they were, would only happen in the future: the 2011 municipal elections, which took place a few days after the speech, were, as in the past, open to men only.

Yet in a country whose only written charter asserts the Koran as its basic law and in which women have few legal rights, let alone the right to vote, the announcement struck many as revolutionary. Liberal Saudis and women activists called the decision “historic,” citing it as further proof that their nearly ninety-year-old monarch was a “reformer.” For their part, members of the government rushed to reassure the country’s powerful ulama—the religious leadership, which adheres to the puritanical branch of Hanbali Islam known in the West as Wahhabism—that the new women members of the Shura would not mix with the men. The king himself, in making the announcement, carefully noted that “since the time of the Prophet, the Muslim woman has had valid opinions and [sound] advice that should not be regarded as marginal.” Even so, prominent Saudi clerics suggested that the decree did not have religious backing, and two days later, as if to assert their continuing writ, a court in Jeddah sentenced a woman to ten lashes for driving a car.

Thus the king’s revolutionary speech was also a deft maneuver to preserve the status quo. On the one hand, the monarch was appeasing one of the country’s most aggrieved constituencies—educated Saudi women—and openly acknowledging that the country’s political institutions must evolve. On the other hand, he left the Saudi system hardly more democratic than before, and by raising the ire of religious leaders, reinforced the divide between the two groups—liberals and Islamists—that pose the greatest threat to the monarchy. “In effect, nothing has changed,” Mohammad bin Fahad al-Qahtani, an economics professor and human rights activist, told me in Riyadh last May. (A few weeks after I spoke to him, al-Qahtani was put on trial for starting an unauthorized human rights organization and could face up to five years in prison.)

The same might equally be said of Saudi foreign policy. Mindful of the political awakening sweeping through the region, the king has shown a degree of support for uprisings elsewhere, from arming the rebels in Syria to reconciling with the new Islamist leadership in Egypt. Yet the only direct intervention by Saudi Arabia has come in neighboring Bahrain, where, in March 2011, a Saudi-led force was sent to stave off a popular revolt and prop up the Bahraini monarchy. Riyadh has also been using its influence in the Gulf Cooperation Council, the alliance of autocratic Persian Gulf states, to pull together support for the beleaguered royal houses of Morocco and Jordan. The White House has remained silent. The US does more trade—overwhelmingly in oil and weapons—with Saudi Arabia than any other country in the Middle East, including Israel, and depends on close Saudi cooperation in its counterterrorism efforts in Yemen.

Indeed there are few signs that the Saudi monarchy is even contemplating serious reforms. During a recent visit to several parts of the country, I spoke to academics, journalists, members of the Shia minority, and young bloggers, as well as clerics and government officials, and many were outspoken in criticizing the government; one journalist who had worked for official media told me, within minutes of our acquaintance, “I can’t wait for this regime to collapse!” But almost without exception, no one seemed to think that would happen anytime soon. I asked one prominent women’s rights activist why more Saudis weren’t agitating for a full written constitution—a moderate reform that could provide a more rigorous legal frame for continued Al Saud rule and that was discussed publicly during a brief opening after the September 11 attacks. She replied: “No one’s talking about it anymore. All the constitutional monarchists have been jailed.”

Advertisement

Among the many enigmas about the increasingly elderly group of brothers who have ruled Saudi Arabia since 1953—the year in which their father, Abdul Aziz, the country’s modern founder, died—is how they have continually evaded the forces of change. Despite Saudi control of the largest petroleum reserves in the world, decades of rapid population growth have reduced per capita income to a fraction of that of smaller Persian Gulf neighbors. Even the people of Bahrain, a country with little oil that has roiled with unrest since early 2011, are wealthier. Having nearly doubled in twenty years to 28 million, the Saudi population includes over eight million registered foreign residents, many of them manual laborers or domestic workers. Illegal migrants, who enter on Hajj (pilgrimage) visas, or across the porous Yemeni border, may account for two million more.

With three quarters of its own citizens now under the age of thirty, Saudi Arabia faces many of the same social problems as Egypt and Yemen. By some estimates, nearly 40 percent of Saudis between the ages of twenty and twenty-four are unemployed, and quite apart from al-Qaeda, there is a long and troubled history of directionless young men drawn to radicalism. The country suffers from a housing crisis and chronic inflation, there have been recurring bouts of domestic terrorism, and the outskirts of Riyadh and Jeddah are plagued by poverty, drugs, and street violence—problems that are not acknowledged to exist in the Land of the Two Holy Mosques.

On top of this, Saudi Arabia also seems to possess several of the attributes that have led to broader revolt in neighboring countries. There is a restive and well-organized Shia minority in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, who have engaged in a series of street protests since early 2011.1 And young men and women all over the country are exceptionally well connected by new media: only Egypt ranks ahead in Facebook usage in the region; a higher proportion of Saudis now use Twitter and YouTube than almost any other nation in the world. This has made it easier to expose alleged corruption by members of the royal family, as one anonymous Twitter user, “Mujtahidd,” with apparent inside sources, has been doing, attracting more than 800,000 followers in the process. (A mujtahid is a scholar with independent authority to interpret Islamic law.)

In stark contrast to the country’s youthful population, the Al Saud dynasty often seems geriatric and disconnected. Though he has worn the crown for only seven years, Abdullah was crown prince for twenty-three years before he became king, and commander of the National Guard for nearly half a century. He has not been in good health; his medical visits to the United States often generate as much comment as his trips as head of state. Moreover, owing to Saudi Arabia’s unusual system of succession, there is little likelihood that a charismatic young reformer will soon ascend to the throne. The current monarch is supposed to designate a successor, or crown prince, from among his younger brothers—the remaining survivors of the founding king’s thirty-seven sons by more than twenty wives—before the monarchy passes to the third generation, many of whose members are already middle-aged.

In 2006, King Abdullah established an “allegiance council” made up of senior princes to ratify succession decisions, a step that also seems designed to reinforce conservatism. Two of Abdullah’s successive crown princes, themselves in their late seventies and mid-eighties, respectively, have died in the past year; the current crown prince, Abdullah’s half-brother Prince Salman, is a comparatively young seventy-six. Meanwhile, there are now some seven thousand princes in the ever-growing royal family, each getting some share of the mostly hidden national budget.

Faced with such intractable challenges, can the US-backed regime survive? Two new surveys of the country, both written since the Arab Spring by veteran American journalists, arrive at dramatically different answers. Karen Elliott House, a former managing editor of The Wall Street Journal, sees a country whose people are “seething” with discontent and whose leadership reminds her of the “dying decade of the Soviet Union.” In her book On Saudi Arabia: Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines—and Future, she envisions a potential “crash” when the crown passes to the third generation.

Covering much the same ground, however, Thomas W. Lippman, a former Washington Post reporter who has been traveling to Saudi Arabia for more than three decades, finds “scant evidence that any substantial portion of the Saudi population wants to replace the regime.” In Saudi Arabia on the Edge, he is generally bullish about a monarchy he regards as surprisingly adaptive and exceptionally well armed with cash. “For better or for worse,” he writes, “the outside world can assume that the House of Saud will stand—provided that oil revenue continues to flow into its coffers.”

Advertisement

2.

Contrary to its desert image, Saudi Arabia is a highly urbanized country in which five large metropolitan areas—Riyadh in the center, Jeddah, Mecca, and Medina in the west, and Dammam on the Persian Gulf—account for more than two thirds of the population. Riyadh, the Saudi capital, is a Houstonian sprawl of offices, malls, and SUV-clogged thoroughfares; it is possible to miss the Grand Mosque if you are not looking for it. More affluent districts are filled with American fast food chains, British department stores, and French hypermarkets. Scruffier neighborhoods, like Bathaa in Riyadh’s Old City, feature the usual array of outdoor market stalls, electronics stores, and long-distance call centers, many of them clearly catering to a large immigrant population from South Asia. Seen from a car window, there is little to distinguish it from large cities in many other countries.

And yet at ground level, everything is different. The SUVs are all driven by men, many of them foreigners: since women are forbidden to drive, it is standard for middle-class households to employ a driver; but it is frowned upon for women to be chauffeured by Saudis (or other Arabs) who are not their husbands or fathers. Though women can purchase the latest upscale Western fashions at almost any Saudi mall, they are expected to wear a black abaya at all times and may be harassed by the Committee to Prevent Vice and Promote Virtue, the country’s religious police, if their hair shows just outside their veils. And in downtown Riyadh, not far from one of the main shopping districts, is a square where public beheadings sometimes take place.

Lippman and House are both sensitive to these disconcerting contrasts. Yet the contradictory insights they draw suggest how hard it can be to get a handle on the Saudi regime. For example, looking at the proliferation of fatwas by different Saudi clerics on issues like gender mixing, Lippman sees a system in which “rules of behavior and appearance are not fully codified,” allowing the ruling family to use religion to tighten or loosen its grip as needed; while House thinks the monarchy has “largely lost control of an increasingly diffuse and divided Islam.”

Regarding Saudi women, however, House finds appalling evidence that some are subjected to “virtual slavery, in which wives and daughters can be physically, psychologically, and sexually abused at the whim of male family members, who are protected by an all-male criminal system and judiciary.”

Both authors lament the Saudi education system, which in the clutches of the religious establishment has produced what Lippman calls “a lost generation” of young Saudis. But Lippman argues that the king has embarked on an “education revolution”—purging school textbooks of “inflammatory material,” spending nearly $4 billion to establish a top-flight coed university north of Jeddah, and sending more than 100,000 young Saudis abroad to study; while House maintains that the government’s vast outlays have produced few results (Saudis still perform near the bottom of international tests) because the “religious-educational bureaucracy remains largely impervious to reform.” The two books concur that the Saudi government has made hardly any progress in weaning itself from oil. For House this shows how “unproductive,” “dysfunctional,” “brittle,” and “ossified” the economy has become. Yet Lippman observes that the steady flow of crude has allowed the regime not only to withstand the Arab Spring but also to “spend hundreds of billions of its revenue” preparing Saudis for a post-oil future.

Where does all this leave the Al Saud monarchy? Is continued rule by what House calls “more old men in their eighties” a symptom of imminent collapse or of exceptional longevity? Certainly, in Jeddah and Riyadh, it is not difficult to find young people who are acutely aware of the freedoms they are denied, and House is probably correct to see multiplying troubles ahead:

High birthrates, poor education, a male aversion to manual labor or service roles, social strictures against women working, low wages accepted by foreign labor, and deep structural rigidities in the economy, compounded by pervasive corruption, all have led to a decline in living standards…. Many of [the] young feel their future is being stolen from them.

And yet apart from the Shia in the Eastern Province, young Saudis have shown remarkably little interest in taking to the streets.2 Confronted with this paradox, House reverts to an unpersuasive account of the national character. Saudis, she insists, are “overwhelmingly passive” and “largely somnolent”; “pervasive social conformity” has made them “sullen”—a word she uses throughout her book—but unable to turn grievances to action.

But there is hardly anything passive about the country’s burgeoning political blogosphere, its growing population of young professionals with American degrees who are bridled by Saudi traditions, or even its leading clerics, some of whom not only issue opinions at odds with the regime but have themselves become powerful voices for reform. After spending years in jail, for example, former radical preacher Salman al-Awdah decries the inability of the leadership to connect with youth and tweets to nearly two million followers about the need for change.

In Jeddah, I met young artists and underground filmmakers who gather in private homes to discuss politics and screen movies in defiance of a general ban on cinemas. Even Buraydah—a deeply religious town in the center of the country that, according to House, is “so conservative that parents there protested the introduction of girls’ schools”—now has a local women’s organization that has taken on women’s rights issues, microcredit schemes, and legal advocacy.3 More important, then, is the matter of how the Saudi government has been able to prevent such social activism from turning against the regime itself.

3.

To a remarkable degree, Western assumptions about Saudi Arabia still begin and end with the Rub al-Khali, or the Empty Quarter, the vast barren expanse engulfing the lower third of the Arabian Peninsula that ranks as the largest sand desert in the world. It was on the fringes of the Empty Quarter that oil was discovered in the 1930s, and it was through experiences among the nomadic Bedu (Bedouins) here that twentieth-century explorers like Wilfred Thesiger introduced Arabia to Western audiences.

From this basis emerged the story that has been taken for granted until today: spurred by the Standard Oil Company of California, a former subsidiary of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, the US government entered into an unshakable alliance with the House of Saud, a powerful tribal dynasty from the Najd (Central Arabia) heartland whose hegemony could be traced back to the eighteenth century. They started by building the US-owned Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco) in Dhahran, near Dammam on the Persian Gulf, which provided for the orderly exploitation of the world’s greatest fuel supply. (The Saudi government acquired part-ownership of Aramco in the 1970s and took full control in 1980.) And then they used Aramco itself to transform what House describes as an “impoverished and backward” land into an advanced nation with almost miraculous speed: Americans provided the skills and bureaucratic expertise; Saudi oil provided the cash; and the Al Saud—backed by the zealous followers of the Islamic reformer Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792)—gave cultural and religious legitimacy to the whole enterprise.

However, very little of this story turns out to be true. The Al Saud did not consolidate power until the third decade of the twentieth century; and important parts of Saudi society were highly developed (and not necessarily under Wahhabi control) at the time oil was discovered. In the Hijaz region on the western coast, there was a tradition of civil association going back for centuries. Before the Saudi conquest, the cosmopolitan Red Sea port of Jeddah had sizable populations of Indians and Europeans who together with powerful local merchants traded in spices and other goods; and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina had large corporations that drew revenues from Hajj services. In the 1920s and 1930s, these and other cities in the Hijaz had political parties, elected councils, and a flourishing press.

For its part, Aramco was far from a benign instrument of enlightened development, as the political scientist and historian Robert Vitalis has shown in devastating detail.4 Brutally exploiting the local population, it produced a workers’ movement in the 1940s and 1950s that at moments threatened to destabilize the country. Indeed, in the early years of oil, the structure of the monarchy itself was open to debate: at the beginning of the 1960s, King Saud, who had succeeded Abdul Aziz in 1953, briefly installed a reform cabinet that included several commoners and set out to establish some form of representative government.

The reasons Saudi Arabia became the authoritarian US client state we know today—rather than the more pluralistic society this early experience might have foretold—is the subject of Sarah Yizraeli’s revelatory new study, Politics and Society in Saudi Arabia: The Crucial Years of Development, 1960–1982. A senior research fellow and Arabist at Tel Aviv University, Yizraeli has managed to penetrate Saudi society from afar in ways that have eluded journalists and scholars with more direct access. Although she is apparently barred from entering Saudi Arabia as an Israeli citizen, she has long had a following among specialists for her mastery of obscure Saudi and international source material. Significantly, she focuses not on the much-studied decades since 1979, during which an Islamist awakening pushed the regime to reassert its Wahhabi credentials and impose sweeping restrictions on cultural life, but on the largely neglected preceding era.

Intricate in its accumulation of detail and nuance, the story Yizraeli tells is nevertheless stark in its conclusions. During the 1960s and 1970s, exploiting its unprecedented oil wealth, Saudi Arabia was able to build with great speed a technologically advanced, economically self-sufficient welfare state. Far from a project driven by the US and Aramco, however, this radical transformation was masterminded by the royal family itself (above all by King Faisal, who after a power struggle succeeded Saud in 1964) and expressly designed to strengthen its rule and neutralize any pressure for political reform.

Described by Yizraeli as “defensive change,” this strategy involved creating a vast central administration that could co-opt competing factions of society even as it broke down traditional tribal loyalties. Crucial to the state were the assertion of the monarchy’s Islamic roots and the consequent need to separate economic development from political and religious institutions, which could not be tampered with; and the embrace of an ideal of broad consensus that served to isolate and marginalize proponents of more radical reforms.

Equally provocative is Yizraeli’s careful dissection of US policy beginning in the 1960s. Up to the early years of the Johnson administration, she observes, the State Department assumed that economic and social development was supposed to produce representative government, and put constant pressure on the Al Saud to open up the political system. “So consistently did the American Ambassadors to Saudi Arabia…highlight the issue of political and social reform,” Yizraeli writes, that at a meeting with then US Ambassador Hermann Eilts, Faisal “once responded by exclaiming: ‘Does the US want Saudi Arabia to become another Berkeley campus?’” But all this came to an abrupt end in the mid-1960s, when Washington began to take a paramount interest in curbing the spread of Nasserism and promoting the US-led industrialization that Faisal championed: “Stop pushing the Saudis on internal reform,” Secretary of State Dean Rusk advised Eilts, “the king knows what is in his own best interest.”

Thus King Faisal, the robust defender of Al Saud absolutism who by the early 1970s had thousands of political prisoners in his jails, quickly became seen in Washington as the ruler who “modernized the kingdom.” In effect, the US endorsed a state-building strategy that brought American companies such as Chevron, Bechtel, and Lockheed Martin billions of dollars of contracts and investments while giving the monarchy and the religious establishment an ever-growing hold on Saudi society. This was a fateful decision. It fostered years of disregard for human rights and an abysmal record of stirring up violent jihadism, and both continue to this day.

When I met the current US ambassador to Saudi Arabia, James B. Smith, in Riyadh last May, he couldn’t have been clearer about the US–Saudi relationship: the three pillars, he said, are oil security, stability, and counterterrorism; pressure on human rights and political change were unproductive. Instead, Washington is actively embracing the mainstream of Saudi youth who, however dissatisfied they may be with their leaders, are now seeking to study in the US as part of King Abdullah’s ambitious scholarship program.

Certainly, sending young Saudis to American colleges should over time have a liberalizing effect on Saudi society. But it also fits with a series of innovations—including the private Red Sea beach clubs where Saudis can wear Western attire, the causeway to neighboring Bahrain, where they can freely indulge in alcohol (and other pleasures), or even the proliferation of gated communities in the Saudi capital itself, where they can live beyond the purview of the religious police—by which the regime can cultivate the most progressive parts of society.

As Asaad Al-Shamlan, a political scientist in Riyadh, explained, what Western eyes may regard as mere hypocrisy might be better understood as an intentional strategy to alleviate social pressures. By granting Saudis a “right to exit” the system, he said, the regime has “effectively derailed momentum for reform.” In this view, by inviting women into the Majlis al-Shura in his 2011 speech, King Abdullah may simply have been opening another escape valve in the established order.

Perhaps as a result, the few dedicated oppositionists one encounters in Jeddah and Riyadh have until now seemed less like the vanguard of a broader movement than as outliers, rejectionists who have fallen through the cracks of an all-encompassing system. (Not coincidentally, they are often punished with travel bans that deny them Al-Shamlan’s “right to exit.”) Indeed, far more young Saudis appear to be concerned about violent upheavals in neighboring countries than about the repressive order at home. In a 2012 survey of Arab youth in twelve countries, a disproportionate number of young Saudis—55 percent, more than in any other country—identified “civil unrest” as the “biggest obstacle facing the region” against only 37 percent who said it was “lack of democracy.”5

If this is the case, then the continued viability of the Saudi regime will depend little on the particular strengths or weaknesses of the current ruler and his immediate successors. Far more important may be the question of whether the overall approach of defensive change—by now deeply embedded in all areas of Saudi society and backed by a vast state bureaucracy as well as an entrenched religious establishment—can continue to persuade a majority of Saudis to support or at least tolerate a repressive government in which they have almost no say.

For decades, the parched kingdom has flourished on the promise that its leaders could turn oil into water and provide the comforts and escapes of advanced Western society without giving up the country’s ultra-traditional religion and culture. With continued oil and US backing, it may continue to do so for years to come. But as soon as Saudis start to believe that the promise is no longer being kept—that the oil revenues that drive the whole operation can no longer sustain domestic needs, a shift that some analysts believe could take place in the middle of this decade—then the future for the Al Saud may be precarious indeed.

—December 12, 2012

Research for this article was supported by the International Reporting Project in Washington, D.C.

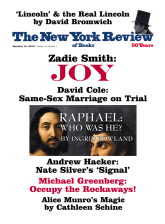

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right

-

1

A full account of the Shia uprising can be found in Toby Matthiesen’s coming book Sectarian Gulf: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Spring That Wasn’t (Stanford University Press, 2013), an early draft of which was kindly shared with the author. ↩

-

2

When a “Day of Rage” protest was announced for Riyadh in the spring of 2011, a single protester showed up. See Madawi Al-Rasheed, “No Saudi Spring: Anatomy of a Failed Revolution,” Boston Review, March/April 2012. ↩

-

3

See Caroline Montagu, “Civil Society and the Voluntary Sector in Saudi Arabia,” The Middle East Journal, Winter 2010, p. 67. ↩

-

4

America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (Stanford University Press, 2007). ↩

-

5

After the Spring: Arab Youth Survey 2012 (ASDA’A Burson-Marsteller, Dubai). ↩