1.

On April 17, 2013, as parents of children gunned down in the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School looked on, the Senate rejected a bill to close loopholes in the federal law that requires background checks of gun purchasers. Background checks, most of which take only minutes to complete, are designed to bar sales to several categories of persons, such as felons, fugitives, drug addicts, people adjudicated as mentally incompetent, and perpetrators of domestic violence. Current law requires federally licensed gun dealers to conduct such checks, but does not apply to so-called private sales, many of which take place at gun shows and via the Internet. This loophole accounts for about 40 percent of gun sales, and therefore radically undermines the effectiveness of the background check regime.

Polls report that 85 percent of Americans, and 81 percent of gun owners, favor universal background checks. One might think that in a working democracy, 51 percent support would be sufficient. But not in this democracy, and not on this issue. The provision fell six votes short of the sixty needed to overcome a Senate filibuster.

The measure that the Senate rejected was exceedingly modest. It was a watered-down compromise drafted by two senators with “A” ratings from the National Rifle Association—Joe Manchin, Democrat of West Virginia, and Pat Toomey, Republican of Pennsylvania. It included several provisions sought by gun rights advocates, including background check exemptions for private transactions between family and friends, and a prohibition on a national gun registry. The two other central features of President Barack Obama’s initial post–Sandy Hook gun control proposal had already been jettisoned—bans on sales of assault weapons and magazines holding more than ten rounds of ammunition.

Yet even the modest compromise forged by two NRA-approved senators could not survive. Some have blamed President Obama for not twisting enough arms, but as Elizabeth Drew has incisively explained, that charge greatly overstates a president’s ability to change a senator’s vote.1 And even if the five Democrats who voted against the proposal had fallen in line, the bill would still have failed.

As a result, more than four months after Adam Lanza killed twenty first-graders, six adults, and himself with a Bushmaster XM-15 assault rifle in Newtown, Connecticut, the national politics of gun control remains where it was—at a stalemate. A handful of states, most notably Connecticut, Colorado, New York, and Maryland, have enacted strict new gun regulations. (Another handful, however, have loosened their gun laws since Newtown, though in less significant ways.) But Congress has done exactly nothing.

Meanwhile, gun violence in the United States continues to far outpace that in other developed nations. Since 1960, more than 1.3 million Americans have died from firearms, either in suicides, homicides, or accidents. By this grim metric, we are unquestionably a world leader. The US firearms homicide rate is twenty times higher than the combined rate of the next twenty-two high-income developed nations. Between 2000 and 2008, there were more than 30,000 gun deaths a year in the US, for an average of more than eighty every single day. And in 2010 alone, emergency rooms treated more than 73,000 people for nonfatal gunshot injuries.2

We read with horror of terrorist attacks around the world, mostly in far-flung places that regularly endure suicide bombings, improvised explosive devices, and the like. We breathe a sigh of relief that we don’t have to live with such violence, while we spend billions of dollars annually to prevent such attacks occurring here. But every year, about twice as many people are killed in the United States by guns than die of terrorist attacks worldwide. Americans face a one in 3.5 million chance of being killed in a terrorist attack, but a one in 22,000 chance of being murdered.

These numbers are staggering, but they are also, of course, much more than just numbers. New York Times columnist Joe Nocera has sought to put human faces to these statistics in a daily blog, The Gun Report, that collects and reproduces, largely without comment, excerpts from the nation’s local media reporting on the gun deaths and injuries of the previous day. The blog makes for brutally sad reading, but it brings home the bleak reality of the gun violence that has become an all too routine feature of our daily lives. It may well be the single most effective example of pro–gun control advocacy being produced today. Here’s an example, taken at random from the April 26 blog:

A woman was shot and killed in front of her young child in Oakland, Calif., Wednesday night. The woman was reported shot at 8:43 p.m. just blocks from Oakland Children’s Hospital. Her 4-year-old son was found unharmed at her side. Two men in a car were witnessed fleeing the scene. It is Oakland’s fourth homicide this week.

—CBS San Francisco

A 10-year-old boy was shot and killed inside his Marengo, Ohio, home Thursday evening. The sheriff says the death is being investigated as an accidental shooting.

—10TV.com

A mother was accidentally shot by her teenage son at their Oakville, Mo., home Thursday evening. The 18-year-old picked up his father’s gun to clean it when it went off, hitting his mother in the leg. She is expected to survive. The victim’s sister-in-law said they are a big gun family.

—KMOV

If we are to break the logjam about gun violence in the United States, the first step is to pay attention to the mayhem that occurs around us. Every citizen should read Nocera’s blog. Tragedy grabs our attention temporarily when a mass shooting occurs in Newtown or at Virginia Tech, but the much broader tragedy is felt every day by victims of less spectacular but equally sad events. Real reform must take on this too often overlooked aspect of daily American life.

Advertisement

2.

The second step to a sane gun violence policy, however, is to recognize that there are legitimate competing interests on the other side of the ledger, and that many Americans value those interests particularly deeply. If proponents of gun control fail to understand or respect the opposing point of view, they may well undermine their own interests in achieving reform.

Guns breed hyperbole on both sides. The NRA has for years warned that any regulation is a step on the slippery slope to a wholesale ban—even after the Supreme Court announced in 2008 that the Constitution precludes outright bans on handguns and ordinary rifles, and even though only about 26 percent of Americans favor banning handguns.3

But liberals are also guilty of hyperbole. Consider, for example, Tom Diaz’s The Last Gun. Diaz effectively describes the substantial costs of gun violence in American life, and asks, justifiably, why we pay so much more attention to terrorism than to gun violence. But his diagnosis is unlikely to persuade anyone who does not already fall in his camp. He attributes the problem to “deliberate suppression of data regarding criminal use of firearms, gun trafficking, and the public health consequences of firearms”; “the almost universal failure of the American news media to report on…gun violence”; gun manufacturers’ marketing of increasingly lethal and militarized weapons; and “widespread acquiescence by elected officials to the gun lobby’s unrelenting legislative campaigns.”

But as Nocera’s Gun Report and any viewing of the evening news illustrate, the media regularly cover gun violence, and as Diaz himself demonstrates, the toll of death, injuries, and crime inflicted with guns is no secret. It’s true that gun manufacturers market their wares, but who would expect otherwise? Guns have become increasingly lethal, but most gun violence is caused by ordinary handguns, not militarized assault weapons. Diaz devotes almost an entire chapter to a detailed description of the very powerful Barrett 50-caliber antiarmor sniper rifle. But he then notes that this weapon has been involved in only about thirty-six criminal incidents nationwide over a twenty-three-year period, or less than two a year. Civilians may not have any legitimate need for such a rifle, but it is hardly the core of the problem.

Diaz’s chapter on the Supreme Court’s decision in Heller v. District of Columbia is similarly vulnerable. That decision essentially overturned a long-standing precedent holding that the Second Amendment protected only the states’ rights to maintain militias in which citizens bear arms, and held instead that the amendment protects an individual right to bear arms. Diaz barely discusses the Court’s reasoning, which concluded that there was historical evidence supporting an individual right. Instead, he dismisses the case as the result of a vast right-wing conspiracy, in which gun rights advocates concocted a test case, funded by a wealthy gun advocate, and supported by the NRA. As Diaz breathlessly sums up, the Heller case was

a snow job produced from the flakes of dabblers in history, created and underwritten by a wealthy philosopher-king from the throne of his Florida condominium, with a cast of thousands from right-wing front groups, the NRA, the gun lobby, the gun industry, and paid-for scholars.

While it is true that the NRA campaigned for many years to obtain constitutional recognition its vision, the same could be said of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s campaign to overturn the doctrine of “separate but equal.” The fact that citizens committed to certain ideals organize, educate, advocate, and file test cases to advance a particular view of the Constitution, and that such efforts cost money, is neither news nor grounds for criticism. It is simply constitutionalism at work.

Moreover, while the Court in Heller recognized a right to bear arms, it simultaneously acknowledged the government’s right to impose reasonable regulations. In particular, the Court noted, the Second Amendment allows the government to ban felons from possessing guns; exclude guns from places such as courthouses or schools; license gun sales; and prohibit altogether dangerous and unusual firearms. Thus, it is politics, not the Constitution, that is the real barrier to gun control these days. And that politics is not aided by expressions of disdain.

Advertisement

3.

Diaz’s dismissal of gun owners’ concerns is not atypical. In Gun Guys, Dan Baum collects a number of examples:

Newspaper editorialists called gun owners “a ridiculous minority of airheads,” “a handful of middle-age fat guys with popguns,” and “hicksville cowboys” with “macho” hang-ups. For Gene Weingarten of The Washington Post, gun guys were “bumpkins and yeehaws who like to think they are protecting their homes against imagined swarthy marauders desperate to steal their flea-bitten sofas from their rotting front porches.” Mark Morford of SF Gate called female shooters “bored, under-educated, bitter, terrified, badly dressed, pasty, hate-spewin’ suburban white women from lost Midwestern towns with names like Frankenmuth.”

Baum rightly concludes, “It was impossible to imagine getting away with such cruel dismissals of, say, blacks or gays, yet among a certain set, backhanding gun owners was good sport, even righteous.”

Rather than offering up yet another book about gun policy, Baum sets out to understand what motivates so many Americans to be “gun guys.” Baum himself learned to love guns when, as a small, young, and not particularly athletic summer camper, he found refuge in his skill at shooting. But he doesn’t otherwise fit the assumed mold: he’s a New Jersey Democrat from a Jewish family in which no one else ever owned a gun, a former staff writer for The New Yorker, and a believer in “unions, gay rights, progressive taxation, the United Nations, public works, permissive immigration, single-payer health care, [and] reproductive choice.”

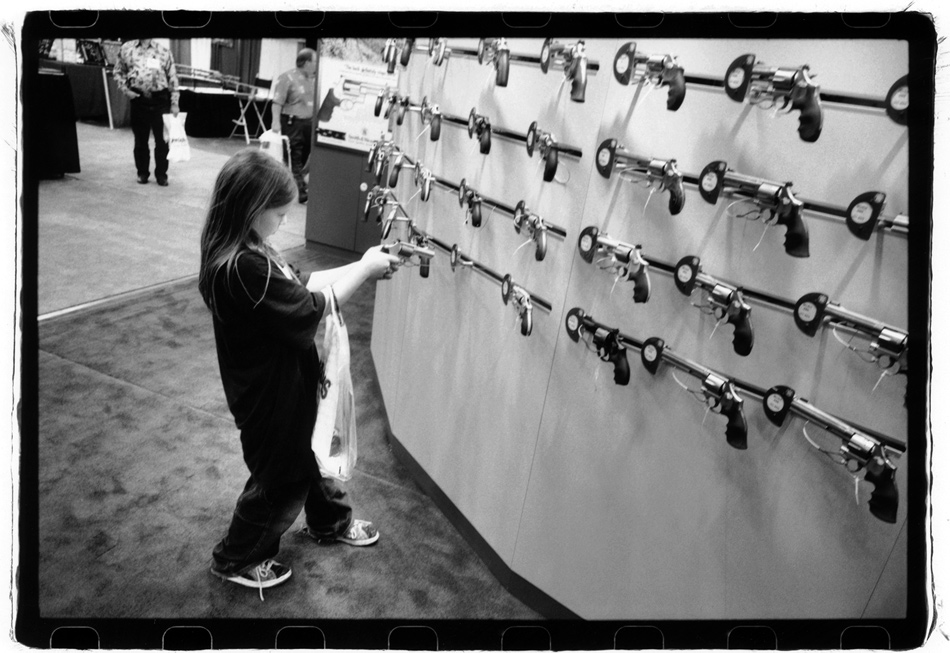

For his journey through gun country, he dons an NRA cap and gets a license to carry his gun in public. As he travels, he is guided by the “Gun Store Finder” app on his iPod. It leads him, as often as not, to boarded-up gun shops, reflecting the reality that gun ownership in America is dropping significantly. In the 1970s, almost half of American households owned a gun, but by 2012, that share had dropped to 34 percent.4

But there are still plenty of gun owners out there, and they come in all shapes and sizes. One in four Democrats has a gun in his home, while 60 percent of Republicans do. In an effort to understand gun owners, Baum interviews and portrays, among others: the founder of Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership; an attractive athletic couple who compete in “run and gun” submachine gun competitions; an enthusiastic machine gun collector; an African-American who buys a gun and becomes a self-defense trainer after he’s robbed at gunpoint; and a former aerospace machinist who now runs a multimillion-dollar company building high-quality assault weapons.

Through visiting with these and other gun owners, Baum identifies a range of reasons underlying the passion for guns. Some are attracted to the gun as an elegant machine, many of which still work perfectly more than one hundred years after their manufacture. Others enjoy the feeling of hyper-alertness that carrying a gun entails. As Baum describes it, wearing a gun heightens one’s senses:

Everything around me appeared brilliantly sharp, the colors extra rich, the contrasts shockingly stark. I could hear footsteps on the pavement two blocks away.

For many, the gun is a means of self-defense. Some thrill to the feeling of power their guns provide; hunters relish the chase and the kill. For still others, as Baum himself found at summer camp, guns are a kind of primitive equalizer, neutralizing natural differences in strength, stamina, intelligence, and the like. Baum quotes a 150-year old advertisement by Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company: “God made all men, but Samuel Colt made them equal.” And for some, such as nineteenth-century Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, the gun is a critical check against government abuse, “the palladium of the liberties of a republic; since it offers a strong moral check against the usurpation and arbitrary power of rulers.”5

Baum depicts these people and their different motives with genuine empathy, for after all, he shares their feelings for guns. But he is more mystified by the broader conservativism that so many of them espouse. As Nate Silver recently reported:

Whether someone owns a gun is a more powerful predictor of a person’s political party than her gender, whether she identifies as gay or lesbian, whether she is Hispanic, whether she lives in the South, or a number of other demographic characteristics.6

Gun rights play an important part in libertarianism, of course; they are a concrete (if largely symbolic) manifestation of the individual’s right to stand up to tyrannical government. But Baum’s interviews also suggest that “gun guys” are driven to conservatism at least in part by their sense that liberals are not only insensitive to, but affirmatively disrespectful of, their interests:

What was also coming through again and again was that gun guys felt insulted. They had something they liked to do—own and shoot guns—and because of it they suffered, they believed, a continuous assault on their hobby, their lifestyle, and their dignity…. At precisely the moment they were sensing their numbers shrinking, gun guys were experiencing what they perceived as a nonstop attack on their very worth as human beings.

Some of the Democratic Party’s best strategists have acknowledged just this concern. In 2013, Bill Clinton warned a closed-door group of top Democratic donors not to dismiss gun owners, saying: “Do not patronize the passionate supporters of your opponents by looking down your nose at them.”7 Democratic strategists James Carville and Paul Begala similarly wrote in 2006 that by disrespecting gun rights, “Democrats risk inflaming and alienating millions of voters who might otherwise be open to voting Democratic.”

Many blame the NRA for the stalemate on federal gun policy, but Baum suggests the issue runs much deeper. The NRA has four million members, but so does the National Wildlife Federation, rarely thought of as wielding outsized influence on Capitol Hill. And while the NRA donates to many political candidates, its donations are often relatively small. As Baum writes, “NRA contributions to congressional candidates were about half that of the pipe-fitters’ union—and when was the last time politicians cowered before the pipe fitters?” He concludes: “It was more comforting, I suppose, to imagine the enemy as a goliath who played dirty than to face the reality: that gun laws were loose because that was the way most Americans wanted them.”

But what are we to make of the fact that even a modest expansion of background checks, supported by 90 percent of the American public, has thus far failed? The outcome may reflect the vastly different degrees of intensity with which proponents of gun rights and gun control hold their respective preferences. The fact that the right to bear arms is tangibly embodied in a prized personal possession, associated in many owners’ minds with self-defense, power, patriotism, and equality, means that gun owners will be more motivated to act on their preferences, to lobby their representatives, and to make the gun issue dispositive in the voting booth. By contrast, it is the rare citizen, Michael Bloomberg notwithstanding, who makes gun control his make-or-break issue.

4.

This doesn’t mean that liberals should shy away from the problem of gun violence. The 1.3 million gun deaths since 1960 demand our attention and action; reducing gun violence is a moral imperative. But if any meaningful reform is to be achieved, it must be done in league with, not in opposition to, many of those who own guns and feel strongly about their right to do so. The way forward requires identifying reforms that would be both effective and respectful of gun owners’ legitimate concerns.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Heller should make consensus easier to achieve. By precluding bans on ordinary guns and rifles, it should reassure gun owners that the slippery slope they have feared is not at hand. And by acknowledging the propriety of reasonable regulation, the Court left the door open to a range of gun reforms short of outright bans. So what should be done?

First, we should abandon efforts to ban assault weapons. Each year murders with all kinds of rifles, including assault weapons, make up only about 3 percent of all homicides in the US. A 2003 study in Jersey City, New Jersey, found that large-capacity magazines figured in less than 5 percent of shootings. The vast majority of gun injuries and deaths are attributable to ordinary handguns. If pushing for an assault weapon ban will do little to address gun violence but will harden gun owners’ resistance to other reforms, is it really worth the cost?

Second, the effort to close background check loopholes should be revived. Universal background checks are eminently sensible, and are reportedly favored by a very large majority of gun owners and nonowners alike. There can be little objection to keeping guns out of the hands of people who are demonstrably more likely to misuse them, such as convicted felons and perpetrators of domestic abuse. Since the present federal background check regime was instituted in 1994, more than two million applications to purchase firearms have been blocked, and many other people have undoubtedly been deterred. More ineligible gun purchasers would be thwarted if the background checks applied not only to federally registered gun stores, as is now the case, but also to the gun shows that account for many gun purchases. Background checks are not a complete solution, of course. Many crimes are committed by people who passed background checks, or who stole their guns. But the fact that the checks are not foolproof does not mean that they are not a sensible reform.

Third, stricter gun safety regulations should be pursued. Far too many gun tragedies occur because children or criminals gain access to guns that were left loaded and/or unsecured. In May, for example, a five-year-old boy in Kentucky accidentally shot and killed his two-year-old sister with a gun his parents had given him as a birthday present and had stored loaded and unlocked. Safe storage laws, requiring that guns be locked and inaccessible to children, have been found to reduce the incidence of gun accidents. Moreover, safety can now be built into the design of guns, essentially making them operate, like password-protected computers, only for those authorized to use them.

Background checks and safety requirements do not disrespect gun owners. They simply acknowledge that some people are not to be trusted with guns, and that it is important to do what we can to keep guns away from them. But if we are to get gun owners’ support for such reforms, we need to make clear that they are not designed to start a cascade toward confiscation or outright bans. And one way to facilitate that would be to acknowledge more openly and respectfully gun owners’ legitimate concerns.

Finally, any effort to address gun violence must also look beyond gun regulation, to the root causes of the violence. As noted above, the vast majority of gun deaths are caused by handguns. The Constitution forbids banning ordinary guns, and Americans do not support such bans anyway. And with 270 million guns already in private hands, it is too late for a meaningful ban in any event. Accordingly, if we want to do something about gun violence, we must move beyond guns themselves, to address the problem at its roots.

Gun violence is not evenly distributed throughout the nation. Young black males die of gun homicide at a rate eight times that of young white males, and the problem is concentrated among the urban poor. In 1995, the national homicide rate was about 10 per 100,000; the rate for Boston gang members was 1,539 per 100,000. The problem in the inner city will not be solved by gun laws alone, but by efforts to respond to systemic poverty, unemployment, gangs, broken families, failed public education, and drugs. Dealing effectively with these causes would reduce gun violence without in any way affecting gun rights, and so should trigger no objections from the NRA. Indeed, if the NRA and gun owners want to preserve their rights and reduce gun violence, they should affirmatively support such initiatives.

Decriminalizing drugs, for example, would likely do more to reduce violence than banning guns. As Prohibition showed, when criminal law bans widely used commodities, a black market arises, and private violence ensues. Better public education, after-school programs, job training, and employment opportunities would also likely reduce gun violence by affording children born into despair a realistic way out. And reducing mass incarceration, which has drastic collateral consequences for the children and families of the incarcerated, would also help.

None of these reforms is easy. A few states have made incremental progress toward decriminalization of marijuana, but drug decriminalization remains politically untouchable in most states and at the federal level. Investing in poor communities is costly. And mass incarceration, because its harms are suffered largely by underprivileged minorities, generates little public outcry.

The public is horrified, at least briefly, by catastrophes like the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Because such a shooting could happen anywhere, everyone can imagine it in his own backyard. But in truth, mass shootings are an infinitesimal part of the problem. Gun violence is concentrated in economically devastated neighborhoods in cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and Los Angeles. And precisely because the problem is focused in these locales, the majority can and does ignore it. Closing background check loopholes and mandating gun safety are sensible and desirable reforms. But if we really want to do something about gun violence, we must go beyond such measures and invest real resources where the problem is most acute.

This Issue

June 20, 2013

What Is a Warhol?

Cool, Yet Warm

-

1

Elizabeth Drew, “Obama and the Myth of Arm-Twisting,” NYRblog, April 26, 2013. ↩

-

2

Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research, “The Case for Gun Policy Reforms in America,” October 2012. ↩

-

3

“Record-Low 26% in US Favor Handgun Ban,” October 26, 2011, at www .gallup.com/poll/150341/record-low-favor-handgun-ban.aspx. ↩

-

4

Sabrina Tavernise and Robert Gebeloff, “Share of Homes With Guns Shows 4-Decade Decline,” The New York Times, March 9, 2013. ↩

-

5

Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution, Vol. 3, section 1890 (1833). ↩

-

6

Nate Silver, “Party Identity in a Gun Cabinet,” FiveThirtyEight blog, December 18, 2012. ↩

-

7

Byron Tau, “Bill Clinton to Democrats: Don’t Trivialize Gun Culture,” Politico, January 19, 2013. ↩