William Gaddis was nineteen in 1942, when he wrote to his mother, Edith Gaddis, saying that the “section man” in his Harvard English class had recommended a book to him:

I got it and turns out to be history of Communism and Socialism—Marxism—enough to make me actively ill—so don’t care about mark in this test but am going to tell him what I think of his lousy piggish socialism &c—sometimes I think he’s turned that way—he recommends many such books—so I’m going to tell him how stinking I think it is and not worry about an E.

One might think this simply callow, a snobbish reflex of class and family, but it does expose the bedrock on which Gaddis later built his idiosyncratic conservatism, just as it points to his unusually candid relationship with his mother.

His parents had separated when he was three and he didn’t see his father again for twenty years. William Gaddis Sr. worked on Wall Street and was mainly prized by his son for bequeathing him his name (“a family as fine and as noble as I feel the name of Gaddis to represent”). Edith Gaddis eventually became the chief purchasing agent of the New York Steam Corporation, a subsidiary of Consolidated Edison. She brought up her only child in her Manhattan apartment and a house in Massapequa on Long Island, and when he was away from home, at boarding school and Harvard, or traveling in the southwestern states and Central America, then in Europe, Gaddis wrote her frequent, often copious letters.

For the first two hundred pages of this book, his mother is his chief—almost his only—correspondent; not because he was short of friends, but because mothers are better than most people at saving their children’s letters. He relied on her to hunt down books for him in New York, be a sympathetic sounding board for his ideas, respond at speed to his requests for money, and be a dependable source of wise advice on everything. In return, he sent her lively commentaries on his life and its frequent changes of scenery.

Gaddis’s college education was interrupted by illness, and ultimately ended when he was suspended from Harvard after a drunken incident involving the Cambridge police. In 1943, he tried to enlist in the Merchant Marine, but was rejected because of albumin in his urine (this seems to have kept him out of the military draft too); otherwise the war hardly ever gets mentioned in his letters, and between girls, shows, and the Harvard Lampoon, of which he became president and editor, he appears to have been too busy to pay much attention to academic classes. After the suspension he never went back to Harvard. He found a job at The New Yorker in the fact-checking department, where he worked for a year before motoring south with a friend to Mexico City, hoping for an opening in journalism.

What he found instead was his vocation as a novelist, and a self-prescribed curriculum for a literary education more intense and driven than his Harvard studies. He asked his mother to send him his Bible and his copy of Worth Smith’s Miracle of the Ages: The Great Pyramid and to buy the abridged, one-volume version of Toynbee’s A Study of History, Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, and Frazer’s The Golden Bough, along with books by Fichte, Saint Anselm, Hesse, and Balzac. His novel, begun in earnest in the spring of 1947, was titled Blague, and he expected to finish it in a few weeks, but it expired on him sometime after he returned to New York in the early summer.

By the end of November that year, he was back in Central America, in Panama, where, under the influence of Toynbee’s grand synthesis of the rise and disintegration (one might say entropy) of successive civilizations, he started work on a new novel. “It is to concern vanity,” he told his mother. Ducdame would evolve over the next seven years into The Recognitions. Besides Toynbee (“that brilliant man has somehow the meaning of meaning, and never in a smart way, you know, like so many of the books now”), the two writers he most revered were T.S. Eliot and Evelyn Waugh. Both were converts, Eliot to High Anglicanism, Waugh to Catholicism, and Gaddis himself was religiously inclined. He was prone to indiscriminate superstition: he associated people with their Zodiac signs and forecasts and he took seriously the prophecies extracted from the Great Pyramid by Worth Smith. To Katherine Anne Porter (whom he’d never met) he wrote:

Reading the prophesies in the Great Pyramid, or Nostradamus, and in Ezekial and Revelation. And have been obsessed with the idea of Armageddon coming in 1949. That we will live to see Good & Evil defined in battle?… This thing (it is still just a thing) that I am trying to work on now ends with that; and so I have put myself under this insane press of time, that it must be done before, just before, this final violence comes.

Porter, understandably, made no reply.

Advertisement

He read the New Testament (“such a wonder”), and discovered Spengler and Ortega y Gasset. In his immediate surroundings of the Canal Zone, with the Jack Benny radio show playing from every window of the identical, gray frame-houses in Pedro Miguel, Gaddis found a suitable symbol for the barren end times of American civilization. As he told his mother:

Because I am an American, and my whole problem lies in American society; that is, in thinking it out, in understanding where that country has gone all wrong, and perhaps eventually being able to contribute something on the way to right it. About 90% of USA needs to be rescued from vulgarity, and it is the responsibility of them—us—all. Doubtless the most critical time in history.

He sounds young for his age (he was twenty-five) and rather priggish in his moralism, but these qualities served him well as a writer who would remain productively surprised and offended by ordinary American life.

In April 1948, he flew from Panama to Costa Rica, just in time to catch the last few days of the Costa Rican civil war, in which he volunteered on the side of the rebels under José Figueres. He lost his rifle, and helped build an airstrip for an incoming arms shipment from Guatemala. In Costa Rica and its “splendid people” he found an ideal counterweight to the vulgar and industrialized United States. “The country here is high and cool, and this city [San José] a model of order and organization.” In another unanswered letter to Katherine Anne Porter, he explained why Costa Rica so appealed to him:

The disinterestedness of all the people, the almost entire absence of grasping, of self-promotion…. Because CostaRica is still traditional—and largely I suppose due to the hold of the Church—and the family is still family, and it is splendid and interesting to see the hospitality that such a traditional society can afford, as to one rootless, which our (eastern) society cannot because it is rootless itself.

This is as much about Gaddis’s own loneliness and deracination as it is about Costa Rica—the country to which, fueled by Toynbee and Eliot and Waugh and Spengler and Ortega, he attributed all the conservative virtues. But “it would not do to stay in this good land,” he told his mother, and in May, barely a month after he arrived, he sailed for New York.

In November he was on the move again, carrying the growing manuscript of The Recognitions, aboard a small Polish passenger ship that stopped in Gibraltar (“a great pile of shale”), from where he made the long train journey to Madrid. In Franco’s Spain he saw the same characteristics of a “traditional” society that had endeared him to Costa Rica, though his difficulties with the language stopped him from looking very far or deep. Some of his observations have an annoying ring today. “There is always some hag who comes to clean up: no trouble in this country over emancipated women, one of Spain’s seductive qualities to the American Boy.”

Throughout Gaddis’s two-and-a-half-year spell in Europe, his most important relationships were with other Anglophones. A chance meeting on the beach at Palamós, a fishing village and resort north of Barcelona, led to a long and close friendship with the English painter John Napper and his wife Pauline. Napper (in 2001 his Guardian obituarist described him as “a large, gentle-mannered man, an expert on everything, with a twinkle of self-parody in his eye”) was five years older than Gaddis, to whom he presented a model existence: an artist independent of fashion, happily married on the second try, living in an ancient mill-house in the Sussex countryside.

Some details of Wyatt Gwyon, the painter in The Recognitions, echo the painting life of John Napper. (Gwyon, a minister’s son from New England, sets up as a painter in Paris, and after initially failing as an artist, begins successfully forging Dutch and Flemish old master paintings.) In Majorca, Gaddis introduced himself to Robert Graves, who would write a blurb for The Recognitions; and in Paris he began an extended love affair with Margaret Williams.

In letters to his mother, Gaddis liked to depict himself as someone repeatedly smitten by beautiful women. Ormonde de Kay, a friend from his Paris days, said in 1993 that Gaddis was “extremely active in the lady-pleasing department.” In December 1948, writing from Madrid, Gaddis asked his mother to find a copy of Norman Douglas’s South Wind and send it to Miss Williams at her New York address, in time for her to read it on the ship to Italy.

Advertisement

Soon the “loveliest lady on the continent” became the primary subject of his letters home. “There is, as you may have foreseen, may have hoped, the sudden gigantic gigantic consideration, of another person. That is Margaret.” He made, and recast, plans for their wedding, and all the while tried to enwrap his mother within the ambit of his love for Williams. “I must say first, again, how fortunate I am in both of you,” he wrote to his mother:

What she is going through is a hideous difficulty on every hand, a financially, psychologically, and the sense of time passing, but she is magnificent about it. And you. I suppose I’ve know this, but not until recently appreciated it so fully. And to have her letter saying this to me,—I just don’t know anything, what to say to you, what to say to your mother! I have been so touched by all that your mother says and does and her attitude…I do love her so much already, can you know that? I do honestly. And think she is magnificent and how lucky you are, and this I, and how exciting it is to have her adored, so quickly and genuinely, by everybody….

In the waterfall of pronouns, mother and fiancée merge ambiguously into one another. But Williams soon put the distance of the Atlantic between herself and Gaddis in his ardor. Five months later he wrote from Seville:

I ’phoned Margaret from Madrid on Sunday. And of course I cannot tell you, how wonderful it was to hear her, nor how sad eventually, the conversation. Oh I tell you, I tell you (you know) what a magnificent, and splendidly brave person she is. I know now that she is having, and has had consistently a ghastly time of the whole thing, paid and paid and paid.

Yet he did not budge from his European perch. The novel was going well, and Spain was again living up to its early promise of being a better, kinder society than was to be found elsewhere. As he told the Nappers:

And the welcome back. People I hadn’t seen in almost two years, and almost all of them servants or bar tenders &c, but glowing welcome, […] It is wonderful, and heart-breaking, this lavishness with nothing, and such friendship isolates me in embarrassment even more, somehow, than London’s civilised indulgence or Paris’s hard, dull, dreary, absurd, pretentious, stupid, tiresome, indifference.

Eventually, at the end of April 1951, he sailed for New York. From his cabin he wrote to John Napper, mentioning a Spanish girl he’d met in Seville, along with a throwaway remark about Margaret Williams: “thinking now that after two to four months in America to re-cross this sea, with either a wife or the Encyclopaedia Britannica in tow.” Although a snapshot dated June 1951 shows Gaddis and Williams together in a country garden, there is no further reference to her in the letters.

It’s hardly a surprise to find that the author of weighty, bitter comedies about the disintegration of social and personal life in America experienced serial disintegrations of his own, but one notes the pattern set by his affair with Williams, and remembers how Ormonde de Kay described his first marriage: “He was a good uxorious fellow. Until they broke up.” Gaddis, by his own account, was always the deserted party who had tried to hold things together as the relationship worsened. Writing in 1993 to his daughter Sarah (whom he could address as a fellow warrior in the marital and literary trenches, since her own first marriage had ended, and she had published her first—and so far only—novel, Swallow Hard), he sent a disillusioned report on his own career as husband and writer:

I know you are discouraged…. As you know I’ve been there myself—right from our start really from just the time you were born, living till then with and for this Great Book I was writing, had written, saw it drop like a shot & started a new life “raising a family”; 2 years writing a long play & saw it as hopeless; 7 years writing another Great Book & saw it drop like a shot…& another marriage with it….

Even as he wrote this, his relationship with his last companion, Muriel Oxenberg Murphy, was speeding to its expiration date, and his last novel, A Frolic of His Own, was heading for publication and the National Book Award.

Gaddis arrived in New York with a pile of pages that by March 1952 had grown to “almost 100,000 words,” or “just barely more than half finished.” For the winter of 1952–1953 he holed up in a borrowed farmhouse outside Montgomery, New York, emerging in the spring with a completed novel of around 500,000 words. By then, he had also signed a contract with Harcourt, Brace, and collected an advance of $1,000, which enabled him to work full-time on revising his enormous manuscript, and ditch his part-time job with the US Information Service, writing propaganda pieces for the magazine America Illustrated. That winter of hectic composition shows. For all its life, inventiveness, and seriousness of intent, The Recognitions is riddled with clumsy sentences to which an author in less haste would have mailed rejection slips. As Homer may sometimes nod, Gaddis can take disquietingly long naps.

One catches glimpses in the letters of the social life that Gaddis was leading in Manhattan when he wasn’t writing. It is surprising (at least it surprises me) to learn that this late high modernist, this fervent disciple of Eliot and Waugh, was not far from the center of another avant-garde, the Greenwich Village Beats. Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Alan Ansen (a Harvard contemporary who’d spent a year as secretary to W.H. Auden) were close friends. Kerouac put Gaddis in The Subterraneans as Harold Sand (“a young novelist looking like Leslie Howard who’d just had a manuscript accepted and so acquired a strange grace in my eyes”). Gaddis spent the winter of 1953–1954 in Ansen’s Long Island house while Ansen was abroad. (“A house that is just the definition of a suburban house,” he told the Nappers. “But there is a vast and very select collexion of books, and a battery of records and machines to play them, and by now I’m almost mad enough to be at home only in an empty house….”)

As the manuscript (there was only one copy) traveled back and forth between Gaddis and his publishers, he grew increasingly frustrated. “Day after day passes in impatient unemployment while I wait for them to finish whatever editorial reading they appear to find necessary,” he wrote to the Nappers in August 1953. By January 1954, the novel had become the “same damned book, same parade of megalomania,” “this thing,” “this piece of present lunacy.” To another friend, “This ‘work’ bores me infinitely, a lousy long boring pretentious adolescent parade of attempts at experience.” In September 1954, it was a “half million word anagram,” and it was in this familiarly glum, pre-publication mood that he met his first wife, Patricia Black, a fashion model and aspiring actor. (“It is strange indeed on this quiet & beautifully grey afternoon, to think that you are somewhere, at this very instant, being real.”)

When at last advance reading copies were ready, in December 1954, he could not disguise his swelling ambitions for the “book which took 7 years trying to explain itself to me,” though he admitted its faults (“The bulk could have been cut down greatly, and some of the tiresome sophomorics…removed”). He arranged for a copy to be sent by Harcourt, Brace to J. Robert Oppenheimer after he read a lecture that the physicist had delivered at Columbia. Quoting Oppenheimer back to himself, he wrote:

I believe that The Recognitions was written about “the massive character of the dissolution and corruption of authority, in belief, in ritual and in temporal order,…” about our histories and traditions as “both bonds and barriers among us,” and our art which “brings us together and sets us apart.” And if I may go on presuming to use your words, it is a novel in which I tried my prolonged best to show “the integrity of the intimate, the detailed, the true art, the integrity of craftsmanship and preservation of the familiar, of the humorous and the beautiful” standing in “massive contrast to the vastness of life, the greatness of the globe, the otherness of people, the otherness of ways, and the all-encompassing dark.”

Even though he had to use another’s words, Gaddis here achieved the best encapsulation of The Recognitions yet written.

Publication day was March 10, 1955, and it brought gigantic disappointment. Granville Hicks in The New York Times Book Review and Maxwell Geismar in the Saturday Review both condescended with faint praise and many strictures, setting the tone for a generally dismal reception. Twenty years would pass before his next novel. The critical and commercial failure of The Recognitions wounded Gaddis deeply, and bred in him a lifelong wariness of publishers (“a razor’s edge tribe between phoniness and dishonesty”). When offended by a bad review, he never forgot: Hicks, Geismar, George Steiner, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt lived on as thorns in his flesh for years after their slighting notices appeared.

He married Pat Black in May 1955, and their daughter Sarah was born in September. He took a job he loathed at Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, where he wrote speeches for senior executives and reluctantly ingested the spirit of corporate capitalism that infuses JR. Meanwhile, The Recognitions began to slowly gather readers in college English departments who delighted in the features that so annoyed its newspaper reviewers—its great length, its profusion of quotations and allusions (has any novel, before or since, had so many?), its thematic intricacies, and its reputation for baffling obscurity. A trickle of letters from professors and graduate students turned into a flood.

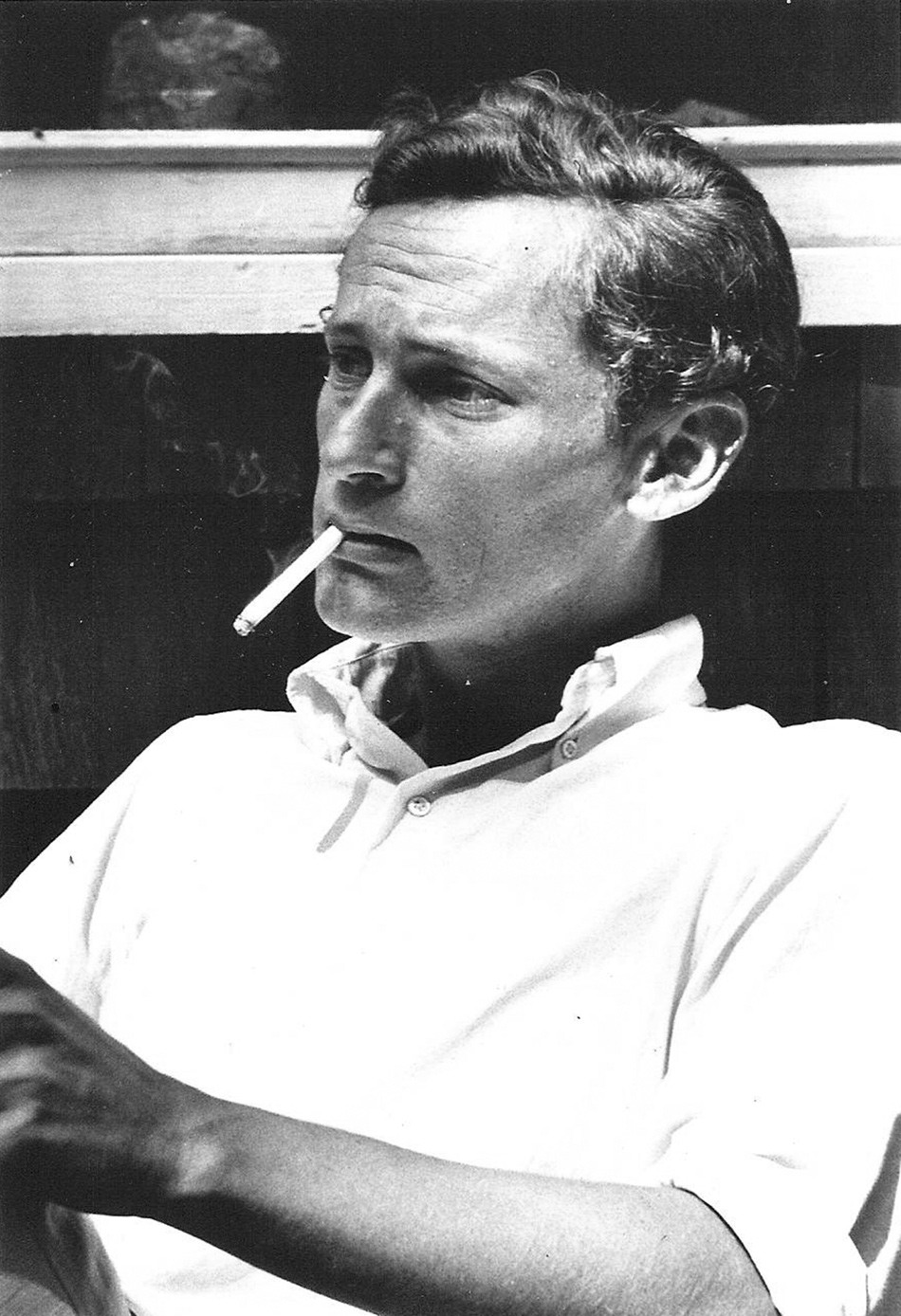

Invitations followed, to conferences and teaching gigs. “What’s any artist, but the dregs of his work?” asked Wyatt Gwyon in The Recognitions; “the human shambles that follows it around. What’s left of the man when the work’s done but a shambles of apology.” Gaddis, never a shambles, always an impeccably sharp dresser, with lean, patrician good looks, became a prized academic ornament. But he never found the “general readership” he craved: “Why am I always the Best Unknown Writer in America?” he asked Joy Williams and Rust Hills in 1977.

JR, Carpenter’s Gothic, and A Frolic of His Own won him a galaxy of honors, including two National Book Awards, a MacArthur “genius” Award, a Lannan Lifetime Achievement Award, and many others, though they had only a small fraction of the sales enjoyed by popular novelists like, say, John Updike or Anne Tyler. He was nearly sixty when the MacArthur Award saved him from the usual hand-to-mouth exigencies of the freelance. He sent a photocopy of the Times announcement to the Nappers:

Can you imagine this! The entire thing a stunning surprise to me & I am still trying to absorb it after those 40 years of mistrustful approaches to the world and fortune: 5 years of “security”!

Puritan frugality was a part of his Gaddis heritage and of his personal character. His well-cut clothes came from thrift stores, and he was careful to recycle every aspect of his experience in his fiction. His travels in Central America and Europe went into The Recognitions; the five-year term he served at Pfizer was turned to profit in JR; his unperformed play, Once at Antietam, became part of A Frolic of His Own; and, at the end, he returned to the first long piece of writing that he’d attempted in his youth, a nonfiction essay on the player piano and the mechanization of art. The Atlantic had published a short excerpt from this piece in 1951.

Forty-five years later, in 1996, Gaddis signed a contract to write a book on the subject, provisionally titled Agapē Agape: The Secret History of the Player Piano, which ultimately turned into the Beckett-like half-soliloquy, half-tirade of a dying man on prednisone (the drug Gaddis took for chronic emphysema) trying to set to rights his manuscript about the history of the player piano. Agapē Agape was first performed as a monologue on German radio, and later published as a novella in 2002, four years after Gaddis’s death. These last words form a single paragraph, ninety-six pages long, composed of epic but barely punctuated sentences that gasp desperately for breath as they swerve and redouble on themselves in the effort to articulate the predicament of art and artists in the industrial and digital age:

That’s what my work is about, the collapse of everything, of meaning, of language, of values, of art, disorder and dislocation wherever you look, entropy drowning everything in sight, entertainment and technology and every four year old with a computer, everybody his own artist….

Steven Moore in his introduction to the letters worries that Gaddis might take a dim view of their publication and of the biography by Joseph Tabbi that is now in progress. More than most writers, he insisted on the primacy of the work over the life, and was temperamentally averse to interviews and journalistic profiles, which he saw as trespasses on his dignity. Yet Moore and Tabbi might take heart from the fact that Gaddis was an avid consumer of literary biography. In 1992, replying to Gregory Comnes, author of The Ethics of Indeterminacy in the Novels of William Gaddis, he quoted from Joseph Frank’s five-volume life of Dostoevsky, whose heroes, losing faith in God, “inevitably destroy themselves because, refusing to endure the torment of living without hope, they have become monsters in their misery.” He went on: “(& to see this rambunctious agony played out in our own time stagger through the marvelous new Stannard biography of Evelyn Waugh vol. 2).”

More than a month later, writing to Jack Green, he touched on the “future threat of publication of my letters even & ‘biography’? which is dull stuff I would proclaim having just finished v. II of Stannard’s marvelous Evelyn Waugh.” It’s true that Gaddis’s letters pale in this comparison (they lack, among other things, the concision, the mischievous invention, the appetite for gossip, the inspired malice of Waugh’s), but they add up to a complicated, rather somber self-portrait of the novelist who always felt himself to be misunderstood, and whose most repeated quotation in all of literature was the complaint in Eliot’s “Prufrock,” “That is not what I meant at all;/That is not it, at all.”