Which artist made the fullest and most engaging picture of the United States in the second half of the twentieth century? In the still-and-mute division of the visual arts, I’d nominate two photographers: Lee Friedlander, whose ceaselessly enchanting exploration of the American social landscape is now in its sixth decade, and his older contemporary Garry Winogrand, who died of cancer in 1984 at the age of only fifty-six but whose take on the American social scene from the 1950s through the 1970s is unsurpassed in range and vitality.

Friedlander and Winogrand were freelance photographers in New York in the 1950s, when picture magazines such as Life and Look were at their zenith, not long before TV began to kill them off. The upbeat aesthetic of the magazines ruled even at the Museum of Modern Art, where Edward Steichen’s feel-good extravaganza of 1955 “The Family of Man” was like a giant walk-in layout from Life. (Winogrand, one of 273 photographers represented in the show, later observed with typical acuity that its chief effect was to make black-and-white editorial photography attractive to advertising.) If magazine editors were indifferent or even hostile to original sensibilities, photography in New York nonetheless was fertile with energy. It was perhaps the last great episode in the medium’s long history of blossoming into art while no one noticed.

The main interest was the city’s streets—and parks, cafeterias, zoos, museums, beaches, stadiums, and airports. The longest-running show with the most varied cast on Broadway wasn’t in any of the theaters but on the sidewalk outside. If Winogrand on occasion needed special permission to enter nightclubs, political gatherings, swank parties, and the like, he was still seeking more of the same prey found in the streets. His pictures of the 1950s, some made on assignment, some on his own, are blunt, unaffected, and full of verve, like the boxers, performers, and regular Joes they describe.

By 1960 Winogrand was working more for ad agencies than for magazines but he was increasingly bored with both, and his personal work began to evolve in a distinct and original direction. His artistic maturity didn’t just emerge from the streetwise vernacular; it was provoked and propelled by the work of Walker Evans and Robert Frank—that is, by a highly sophisticated if then still-underground tradition. Winogrand once remarked to me that “Walker Evans did not exist for the ASMP”—the American Society of Magazine Photographers. (The irony is that Evans was hidden in plain sight on the staff of Fortune, while his great work of the 1930s languished in oblivion.) An eloquent champion of that underground tradition soon arrived in the form of Steichen’s successor at MoMA, John Szarkowski, who in 1963 reasserted the museum’s obligation to independent artists with an exhibition titled “Five Unrelated Photographers,” one of whom was Winogrand. Four years later “New Documents” grouped Winogrand, Friedlander, and Diane Arbus—very different artists who shared impatience with the tired imperative that photographs of the social world must strive to improve it. Their aim, wrote Szarkowski, was “not…to reform life, but to know it.”

Three Winogrand shows followed at MoMA, each accompanied by a book: “The Animals” in 1969 (zoo photographs of the early 1960s, selected by Szarkowski); “Public Relations” in 1977 (photographs of demonstrations, parties, and other group events, selected by the photographer Tod Papageorge); and a posthumous survey organized by Szarkowski in 1988, with a catalog titled Winogrand: Figments from the Real World.

“Garry Winogrand,” the first retrospective in twenty-five years, is an ambitious reconsideration of Winogrand’s unruly art, organized by guest curator Leo Rubinfien with Sarah Greenough of the National Gallery of Art and Erin O’Toole of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. That San Francisco was the original venue of a show that will go on to four other cities was no surprise; SFMOMA has helped to make its city one of the world’s most hospitable to the art of photography.

Photography inescapably but surreptitiously transforms what it describes. If you want your picture to look the way the scene in front of you feels, you are likely to be disappointed, and no matter how the picture turns out everyone else is likely to assume that the camera simply copied what was there. But along with probable failure there is the rare chance of backdoor success: a fortuitous scene that never existed but carries the authority of reality copied by the camera.

All good photographers know this intuitively. I doubt that those who also know it as a proposition thereby gain a creative advantage, but for Winogrand it was at once a captivating intellectual puzzle and a catalyst to his best, most original work. That work, made in the 1960s and 1970s, marks the high point of the formal evolution of a small-camera tradition reaching back to the late nineteenth century. Like Aleksandr Rodchenko, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, and countless others, he used a 35mm Leica. Comfortably held in one hand, it permits up to thirty-six exposures in rapid succession before the roll of film must be replaced. Photographing with such a camera in a busy street is a physical art of acrobatic anticipation whose stakes rise with the number of moving figures in the picture. Winogrand was justly celebrated for his ability to emerge with pictures that coherently arrange half a dozen or more sharply rendered characters.

Advertisement

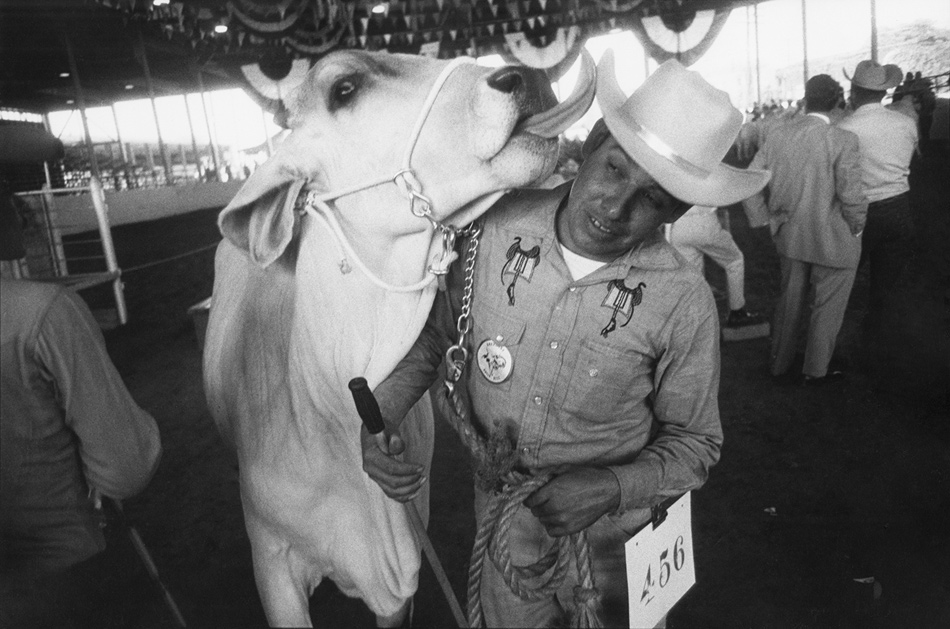

It is easy to misconstrue that ability as a talent for capturing reality, whereas precisely what thrilled Winogrand was the difference between reality and the descriptively rich pictures he derived from it. A 1964 shot (not in the exhibition) at the Texas State Fair is enlivened by an improbable symmetry formed by the curled tongue of an affectionate cow and the brim of the wrangler’s hat—or rather, by the shapes they make in the picture, and in the picture alone.1 Had Winogrand been standing a bit to the left or right, the serendipitous symmetry would never have materialized. There is no conflict between the nominal subject and the pictorial pun, which simply adds brio to the intimacy between beast and man (or as Winogrand would have insisted, between the two animals).

To measure Winogrand’s creative leap of the 1960s, Szarkowski adopted as a baseline a beguiling series of pictures made in 1955 at New York’s El Morocco nightclub, with its zebra banquettes, polished celebrities, guys and dolls. He wrote:

If a time machine could have brought those scenes and actors back to Winogrand a decade later he would have made different pictures. The people in the earlier pictures—free agents with their own agendas, improvising their own one-liners—would have become players in a more complex drama, serving roles within a larger design of which they are unaware.

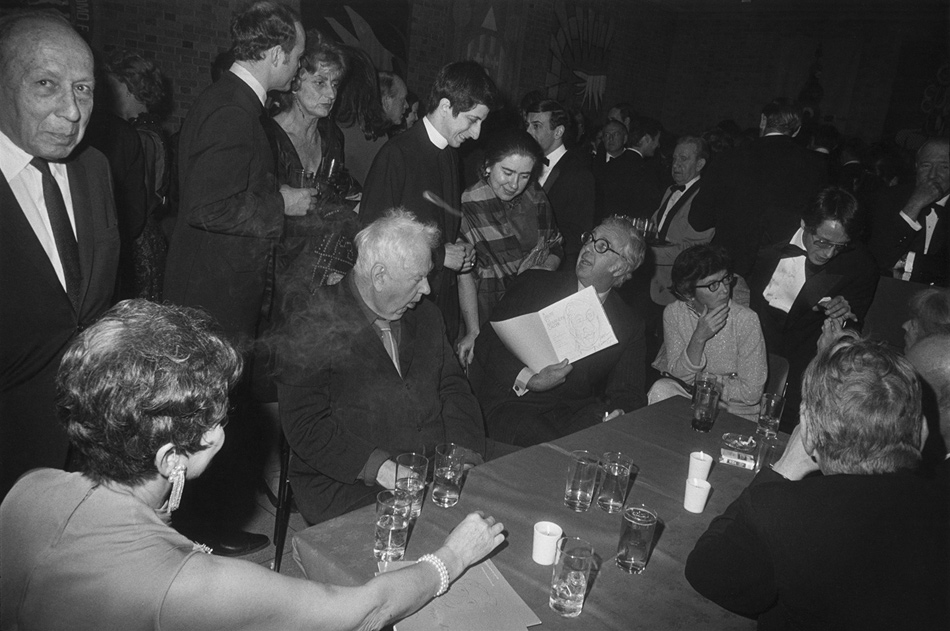

Such a design inhabits a photograph made by Winogrand at the opening of an Alexander Calder show at MoMA in 1969,2 which Papageorge parsed as follows:

The frame is tilted and the old man’s slightly lolling head seems to attract and bear the entire weight of the photograph. Around him we can trace a perfect arrangement—people splayed across the picture plane, gesturing, smiling, talking—a suspended cartwheel of form that owes nothing to a conventional idea of pictorial structure.

Meanwhile a smoke ring has drifted over Calder’s head, nicely silhouetted against the black costume of a perfectly placed priest and canted at just the right angle to serve as the secular saint’s halo.

Winogrand’s mature work creates a charmed realm in which the pungent taste of experience pervades what can seem to be flagrant fantasies. The Calder scene exemplifies his observation that the best photographs clarify the photographic conundrum without ever resolving it, for it simultaneously delivers the documentary goods—have you ever seen a better photograph of a fancy museum dinner?—yet pulls the rug out from under the whole documentary idea. It is at once fact and fable—a figment from the real world.

Winogrand always resisted discussing what his pictures might mean. Partly in consequence his art, though as rich in social content as that of Balzac or Daumier, was often dismissed as “formalist”—narrowly concerned with how photography remakes the visible world. In his catalog essay Leo Rubinfien rightly insists that Winogrand’s photographs are bursting with meanings and emotions that can no more be ignored than they can be reduced to pat lessons and sentiments.

And Winogrand’s range was very broad, from cartoonish satires to scenes of wrenching sadness. In a picture made in Dallas in the summer of 1964, less than a year after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Dealey Plaza has become just another diversion for a cigar-chomping rube in a porkpie hat and other tourists armed with cameras and postcards of the Texas Book Depository. Five years later in Los Angeles, Winogrand trained his eye on three dressed-up women who were about to walk by a scrawny young man slumped in a wheelchair with a beggar’s cup between his knees, as the setting sun behind them drew an elegant design of elongated shadows on a sidewalk embellished with stars dedicated to Hollywood’s winners.

“Garry Winogrand” at SFMOMA included 276 prints, supplemented by absorbing displays of other work and ephemera assembled by Susan Kismaric, who also compiled the catalog’s valuable chronology. With 401 plates, the catalog has many more pictures than the show. Both have three sections: “Down from the Bronx” (New York City, mostly Manhattan, from 1950 to 1971); “A Student of America” (the rest of the country in the same period, plus the work covered by Public Relations, much of it made in New York); and “Boom and Bust” (mostly Texas and Southern California from the early 1970s through 1983). More than half of the pictures in the first section are unknown or unfamiliar—an astonishing proportion for an artist of Winogrand’s stature who died nearly three decades ago. This distinctive contribution of the exhibition and catalog is full of delightful surprises.

Advertisement

The second section gives prominence to a cross-country trip of 1964, during which Winogrand productively applied the stylistic flexibility that he had developed in Manhattan to less familiar places and people. As Rubinfien points out, Winogrand was awed by Robert Frank’s The Americans (1959) but faulted it for missing the main story of the 1950s—the rise of the suburbs. He later backed up that criticism by leaving his beloved New York for Austin, in 1973, then Los Angeles, in 1978. He was convinced that Texas and California were vital incubators of contemporary American life, and some of his best work of the 1960s had been made there. A 1964 picture of a sun-struck split-level house in a Los Angeles suburb, for example, shows a slim young woman standing a few steps from her car in the doorway of the dark garage. We are too far away to read her expression, and we sense meaning in our distance. Is the viewer a voyeur, or perhaps a detective looking for trouble in paradise?

The third section of the exhibition includes pictures from a body of work made between 1974 and 1977 at the Fort Worth Fat Stock Show and Rodeo, which Winogrand published in 1980 as Stock Photographs—his last book. The remainder of this final section raises practical considerations that take some explaining.

In Winogrand’s now all but obsolete working process, an exposed roll of film was developed, dried, cut into strips, and printed by contact with light-sensitive paper to make a sheet of thirty-six positive images, each about 1 x 1½ inches. The contact sheet was marked to identify candidates for enlargement, often work prints that would be winnowed further before finished prints were made. In such small-camera photography, failures greatly outnumber successes, so choosing the successes is nearly as fundamental as making the exposures.

Especially in the bygone era of darkroom drudgery, photographers generally preferred shooting to dealing with the consequences, and it was not unusual that a substantial backlog of processing and editing would accumulate. Winogrand was a prolific shooter and reluctant editor who died young and quite suddenly, and he left behind 6,600 rolls of film that had never reached the stage of contact sheets, plus 3,000 contact sheets that he had hardly begun to edit—a total of some 330,000 unconsidered exposures.

In preparation for the 1988 MoMA retrospective, Szarkowski enlisted Papageorge and the photographer Thomas Roma to help review the giant backlog. (I worked for Szarkowski at the time but had no direct part in the project.) The exhibition’s 190 prints included twenty-five made from the backlog, displayed as “Unfinished Work” along with a slide show of forty additional images—a way of presenting a richer sample without unbalancing the exhibition. Some experts had reservations, but I believe the consensus now is that it was and is appropriate to explore the large body of exposures that Winogrand made but never saw, on the strict condition that posthumously selected images are so labeled and quarantined from the rest of his work.

While following those sensible rules, the organizers of the SFMOMA exhibition have gone much further in reconsidering Winogrand’s work, on the premise that his chronic resistance to editing and his early death conspired to render his entire career unfinished. With permission from his estate and the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) at the University of Arizona, where his archive resides, Leo Rubinfien reviewed more than 20,000 contact sheets (some 750,000 individual photographs) from 1950 to 1983. He selected a substantial number of previously unprinted images, which make up more than a third of the exhibition and an even greater proportion of the plates in the catalog.3 It’s a fresh adventure even for those who know the artist’s work well.

In an ideal world, the responsibility for choosing which images belong to a photographer’s work would be reserved for the photographer. The exhibition makes a persuasive case that we can experience Winogrand’s full achievement only if curators and editors undertake a share of that responsibility, and Rubinfien and his collaborators deserve our gratitude for confronting that daunting challenge forthrightly and ambitiously. My reservations about the project are not philosophical or ethical but artistic.

Rubinfien stresses that four of the five books that Winogrand published in his lifetime were limited to particular themes, and he was planning a fifth, on airports. In structuring the 1988 retrospective, Szarkowski adopted those five themes and added three more—“Eisenhower Years,” “The Street,” and “On the Road”—plus “Unfinished Work.” Rubinfien’s much simpler structure has the advantage of accommodating both individual pictures and the thematic groups that were Winogrand’s own way of giving shape to his work.

Unfortunately, though, coherent bodies of work established in the artist’s lifetime—notably The Animals and Public Relations—are diminished by rather arbitrary tinkering, and the catalog’s other groupings and juxtapositions are less often felicitous than awkward or even jarring. The problem was less acute in the galleries in San Francisco, which permitted far more flexible combinations than do the two-page spreads of the catalog. Rubinfien regrets that, unlike Evans and Frank, Winogrand never in his books exploited the poetic potential of deliberate juxtapositions or sequences of photographs. But the pairing he cites as an example of that potential features an irksome equivalence between the gaping mouths of a monkey in one picture and an old crone in the other. This saps each photograph of its strength by grotesquely exaggerating the significance of a single detail.4

Absent from the show are at least a dozen outstanding photographs that are indispensable to such a large retrospective—omissions that are particularly puzzling since we see many lesser pictures. The hunt for exciting discoveries and perhaps also a sense of mission to redefine Winogrand’s legacy may have deflected the retrospective from its fundamental if banal obligation to present the best work, whether familiar or not. That concern is compounded by the lack—in a catalog otherwise dense with scholarly apparatus—of any analysis of the CCP archive in Arizona, beyond the negatives and contact sheets that Rubinfien studied extensively.

There are 30,000 lifetime prints—work prints and finished prints (ninety-three of which were borrowed for the exhibition)—as well as other resources. Winogrand left a great deal undone, but he also left many clues to his own sense of the work he accomplished through the early or mid-1970s. At the CCP, for example, is a video record of 150 or so photographs shown there as projected slides by the artist on February 4, 1982—a survey of his work beginning in the 1960s selected by Winogrand himself just two years before he died. The absence of a thorough assessment of such clues is all the more unfortunate given the considerable emphasis the exhibition granted to the late work that Winogrand himself never saw. Despite these drawbacks the exhibition was enormously welcome, for it boldly set Winogrand’s obstreperous genius on a suitably august stage.

A photographer whose studio is the street must deal with what the street has to offer, then and there. Winogrand had the great good luck to do his best work in the 1960s, when letting it all hang out emerged as a cultural ideal and a colorful cast from hippies to hard hats earnestly performed for the camera at countless rallies, sit-ins, marches, parties, and demonstrations. Rubinfien makes this central point but elaborates it into an overarching exegesis in which Winogrand’s personal life, his art, and the life of the nation meld in a grand design.

Winogrand apparently lost his bearings in his last years in Los Angeles, and it is reasonable to suggest that he was picturing his own plight when he photographed the distressed, solitary figures that appear frequently in his later work. But Rubinfien’s eagerness to interpret the whole of Winogrand’s artistic career with respect to his personal biography is too insistent. Least persuasive of all is Rubinfien’s attempt to match a rigid equation of art and life to an oversimple template of contemporaneous American experience—confidence and optimism in the 1950s, crisis and frantic self-expression in the 1960s, and dissolution and despair in the 1970s:

It can seem that the emotion in his work follows a large arc, with an ascent, an apogee, and a descent, roughly parallel to the course Americans followed en masse through three critical decades of their history.

This scheme is just the sort of neat package that Winogrand instinctively ripped apart. But Rubinfien is convincing when he writes in conclusion that the artist’s subject was America’s conflicted experience of freedom. Winogrand used that freedom to create an extravagant if unfinished gift—flamboyant, provocative, hilarious, heartbreaking, and inexhaustible.

-

1

Winogrand: Figments from the Real World, p. 145. ↩

-

2

Public Relations, p. 107. ↩

-

3

The posthumous prints are scrupulously identified in the show’s picture labels, though the catalog needlessly forces the reader to flip repeatedly from the plates to the list at the back. None of the prints will appear on the market. Unaccountably, however, an image that Winogrand never saw (Los Angeles, 1980–1983) was chosen to market the exhibition for everything from postcards to magazine ads to street posters, none of which spells out its equivocal status. That the image was part of “Unfinished Work” at MoMA in 1988 does not make it any less unfinished now. ↩

-

4

Plates 23 and 24 in the catalog. ↩