1.

Almost from the beginning of its history, America has struggled to find a balance in its foreign policy between narrowly promoting its own security and idealistically serving the interests of others; between, as we’ve tended to see it in shorthand, Teddy Roosevelt’s big stick and the ideals of Woodrow Wilson. Just as consistently, the US has gone through periods of embracing a leading international role for itself and times when Americans have done all they could to turn their backs on the rest of the world.

Two new books now join this never-ending debate: Henry Kissinger’s World Order and America in Retreat by Bret Stephens, a Pulitzer Prize–winning foreign affairs columnist for The Wall Street Journal. Both sound a call for more powerful and more engaged US leadership around the globe. Both Stephens and Kissinger appear to be worried about a return to isolationism, or at least a more inward-looking American policy, and are doing what they can to head it off. Both offer their own view of the relation between US interests and US values. Stephens’s formula, roughly speaking, is 90 percent interests, 10 percent values, when convenient. Kissinger frames the debate more elegantly as one of power vs. principle, but he often comes down on both sides of the fence.

Beyond this, the books have little in common. Stephens’s is a facts-be-damned polemic, designed to show that the world has gone to hell since President Obama took office. Somehow, Obama is saddled with responsibility for the success of North Korea’s nuclear program. Stephens does not say that North Korea began the program in the 1950s, succeeded in building its first bomb twenty-two years ago, and carried out its first atomic test three years before Obama took office.

He also makes the serious charge that Russia has achieved “nuclear superiority over the United States via the [Obama administration’s] New START Treaty.” He does not acknowledge that today the US has many more deployed strategic launch vehicles than Russia, and that the two sides have equal numbers of warheads and launchers (including those not deployed). Moreover, the US arsenal is much more able to survive an attack than Russia’s and is almost certainly far more lethal. His claim is baseless.

Yet to his credit, Stephens is explicit and unapologetic in defining what he thinks the posture of the US should be, namely the world’s policeman or, as he describes it, a cop walking a global beat, “reassuring the good, deterring the tempted, punishing the wicked.” The metaphor fails because police are servants of the law. Without it, a policeman is merely a vigilante with no independent legitimacy. What Stephens describes is a world in which the US alone decides what behavior it considers unacceptable and rides out to punish it. To my knowledge, he is the only serious analyst ever to have explicitly advocated that the US act as the world’s policeman.

By contrast, Kissinger’s book, steeped in history, is a learned, thoughtful, often fascinating global tour through the various clashing views of world order that are present today and go as far back as the fourth century BC. Its perspective throughout (even for events that occurred more than a millennium before the negotiators met) is the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years’ War. The book’s center of gravity is eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe. Its heroes are “great statesmen,” specifically Cardinal Richelieu, Klemens von Metternich, and Otto von Bismarck, about whom Kissinger has written admiringly for many years. They deserve the highest accolade because they had to

know where [their] strategy is leading and why…[and] act at the outer edge of the possible…. Because repetition of the familiar leads to stagnation, no little daring is required.

The book sheds much light on the past but has surprisingly little to say about the present or the future. Since no one alive has thought longer or harder about diplomacy or had more experience and success working at its highest level, it is disappointing that at age ninety-one Kissinger continues to keep his powder dry. He sets up the right questions, gives the political frame and the historical setting, but then does not share with us his answers to the tough choices the US and others currently face.

The recommendations for policy he does make are too few and far too general to be of much help. On Syria, a country now being destroyed, where a human catastrophe is unfolding, all he offers is a description of the obvious: “If order cannot be achieved by consensus or imposed by force, it will be wrought, at disastrous and dehumanizing cost, from the experience of chaos.” Surely a commentary on world order should provide greater insight into what to do about its worst breakdown in decades. Nor does Kissinger offer a word about the other great challenge to the postwar order, namely Vladimir Putin’s snapping up of Crimea and his stealth invasion of Ukraine. Though the book discusses Asia’s new leaders—Chinese President Xi Jinping, Japan’s leader Shinzo Abe, and Narendra Modi, India’s just-elected prime minister—Putin, Russia’s leader for fifteen years, is not mentioned except for one passing reference. After fifty pages on Islamism and the current troubles in the Middle East, Kissinger vaguely concludes:

Advertisement

The drift toward pan-regional sectarian confrontations must be deemed a threat to world stability…. The world awaits the distillation of a new regional order by America and other countries in a position to take a global view.

Is this really America’s job, or within its power to effect? One wishes that this statement was the chapter’s beginning, or at least its middle, not its last word.

2.

Since the US took on international leadership at the close of World War II, the debate over interests and values has become entangled with others that are importantly, if subtly, different. One is whether the US should usually choose to act alone, or try instead to achieve the greater legitimacy—and restrictions—that accompany multilateral action. Unilateralist views reached a new high in the George W. Bush administration. Those of John Bolton, briefly ambassador to the UN, were characteristic:

It’s a big mistake for us to grant any validity to international law, even when it may seem in our short-term interest to do so—because, over the long term, the goal of those who think that international law really means anything are those who want to constrict the United States.

Setting aside the matter of legitimacy, even a cursory look at the vast body of international law developed over the past seventy-five years—from trade and banking to human rights and arms control—reveals how deeply American interests have been served by it.

Closely related to that debate is the argument over American exceptionalism. American contributions to international security, global economic growth, freedom, and human well-being have been so self-evidently unique and have been so clearly directed to others’ benefit that Americans have long believed that the US amounts to a different kind of country. Where others push their national interests, the US tries to advance universal principles.

At its extreme, this reasoning holds that the US should not be bound by international rules, even those it has itself developed, but should occupy a position above the rest. In this view, it is in the world’s interest, not merely the American interest, for the US to do so. A month after the attacks of September 11, 2001, Max Boot of The Wall Street Journal called on America to unambiguously “embrace its imperial role.” “The organizing principle of empire,” according to the like-minded Stephen Rosen in The National Interest, “rests on the existence of an overarching power that creates and enforces the principle of hierarchy, but is not itself bound by such rules.”

Weaving together these and similar themes in America in Retreat, Stephens argues that the US must now shoulder the responsibility for establishing and maintaining a global Pax Americana. All the alternatives, including traditional balance of power and collective security, have been tried and failed. Americans “mainly want to be left alone,” but instead have to “sharply increase military spending to upwards of 5 percent of GDP” (i.e., by a third or more from today’s 3.8 percent); “once again start deploying forces globally in large numbers”; and be prepared to undertake “short, mission-specific, punitive police actions” around the globe.

The basis for such a drastic shift is his belief that international security is skidding downhill. The evidence suggests otherwise. The number of armed conflicts is down by more than one third since the end of the cold war. By 2008, high-intensity wars (i.e., those with an annual death toll of one thousand or more) were down by nearly 80 percent. Because most conflicts since the cold war have been within states rather than between them, the average war is costing one thousand battle deaths per year rather than the ten thousand average of the 1950s. This is not to diminish the seriousness of the many threats that abound today—conflagrations in the Middle East, the conflict in Ukraine, the tensions in the East and South China Seas, Islamist terrorism, and Iran’s nuclear program. But when there is saturation coverage, with video, of deaths by ones and tens, the overall impression of peace and war can be misleading.

Surprisingly, perhaps, recent years have also been ones of declining threat from weapons of mass destruction. There are now far fewer nuclear weapons in the world and fewer countries with nuclear programs than there were twenty years ago. During the last half-century, just four countries (Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea) acquired nuclear weapons: too many, but far fewer than experts dared hope for when the Nonproliferation Treaty was signed. Chemical weapons were banned in 1997. One hundred and ninety countries have agreed to be bound by that treaty and more than 80 percent of nations’ declared stockpiles have been destroyed. It was because that widely accepted treaty existed that international action could be taken against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad following his use of chemical weapons. The US blundered badly through that episode, but in the end a strong precedent was established: use these weapons and you will lose them.

Advertisement

Where, then, does Stephens get his sense of impending doom? Discussing why American elites have periodic attacks of what he calls “declinism,” he writes, neatly, that it is partly

the continuation of partisanship by other means—a handy way for those who are out of power to accuse those in it not only of bungling the job, but of putting the country on the road to ruin.

This is both true and an apt description of his own book.

The Pax Americana, Stephens writes, includes “freeloaders” who take advantage of American security guarantees and military spending and, worse, “freelancers, constantly taking unpredictable chances with their own security”—in other words, countries with the temerity to think that they have a right to their own foreign policy. In short, Stephens urges a fantastic construct: a global hegemony in which two hundred–odd nations calmly accept both one country’s right to decide what is and isn’t acceptable behavior and to accumulate, unopposed, a sufficient margin of power to enforce its rulings. Nothing like it has ever existed—or ever will.

3.

Henry Kissinger’s World Order is anything but ahistorical. It is actually two books folded together, a wide-ranging survey of the various conceptions of world order (there never has been a world order) and—building on Kissinger’s portrayal of America’s changeable international past—a call for US leadership in every region, lest a “vacuum” develop. His plea is that America recognize its “indispensable role” by at last “coming to terms with that role and with itself.”

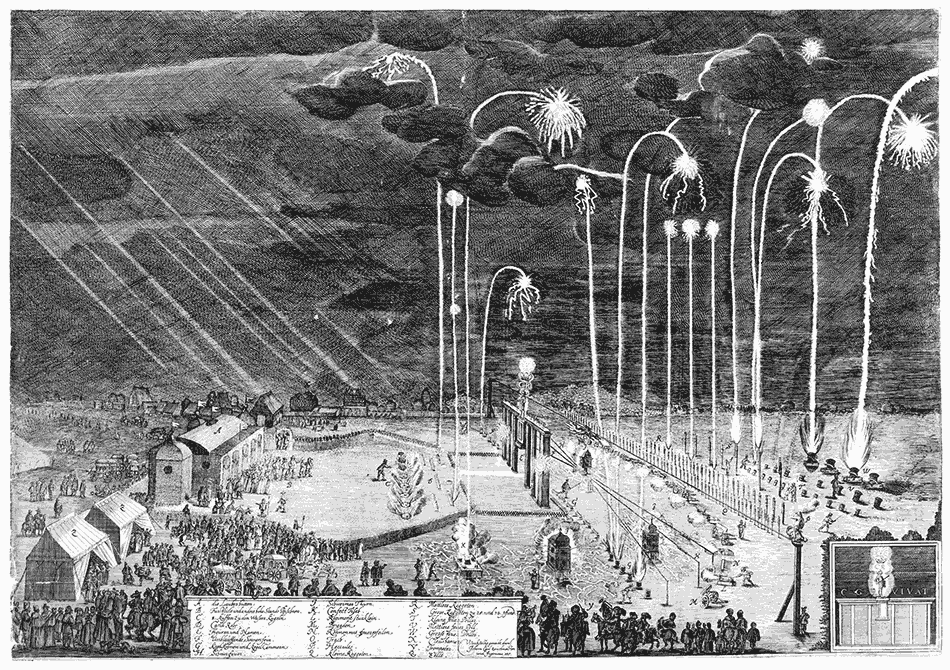

What we have now, “the sole generally recognized basis of what exists of a world order” and the central subject of this book, are the principles of state sovereignty that emerged from a series of negotiations in northern Germany over 350 years ago. Kissinger describes the history of the Peace of Westphalia wonderfully, noting that the Holy Roman Empire alone was represented in those meetings by 178 separate participants from its various states.

From the mass of overlapping rulers—emperors, kings, dukes, popes, archbishops, guilds, cities, etc.—the Peace of Westphalia produced a solution of dazzling simplicity and longevity. The governing unit henceforth would be the state. Borders would be clearly defined and what went on inside those borders (especially the choice of religion) would be decided by its ruler and a matter of no one else’s business. In modern terms, the delegates invented and codified state sovereignty, a single authority governing each territory and representing it outside its borders, no authority above states, and no outside interference in states’ domestic affairs.

From 1648 until at least the end of the cold war, power became concentrated steadily in the hands of states, though Westphalian principles were never universal. In a historical tour d’horizon, Kissinger traces the different challenges to the Westphalian system—from Russia under the tsars and later the USSR, Japan and China under their respective emperors, India in its pre-British history, and today the Islamic Republic of Iran (in which a state and a religion share sovereignty), and, finally, the Islamist forces that hope to substitute a religious caliphate for secular states. Nonetheless, Westphalia gave birth to international relations as we know them and to the balance of power among legally equal entities.

The historical argument is acute. But the book is weakened by attempting to force just about everything states do into this single frame. Iranian and American nuclear negotiators are in “a contest over the nature of world order.” Even the EU, which as no one knows better than Kissinger is a historic rejection of Westphalian sovereignty in favor of something new,

can also be interpreted as Europe’s return to the Westphalian international state system…this time as a regional, not a national, power, as a new unit in a now global version of the Westphalian system.

Though the EU has a high representative for foreign affairs and an External Action Service, its members emphatically do not (and may never) represent themselves to the outside world as a single entity. National capitals take the lead.

Across the Atlantic, America’s encounter with world order derived from its belief in its special destiny as the engine of human progress. Its history produced a society with, as Kissinger puts it, “congenital ambivalence” between the pursuit of moral principles and national interest. Teddy Roosevelt came close to a synthesis, Kissinger believes, and had he won reelection in 1912 “might have introduced America into the Westphalian system.” By bringing America early into World War I he might have thereby changed the course of world history.

Instead, Woodrow Wilson took office, and was all too successful in connecting with what Americans have always wanted to believe about themselves. His genius was to “harness American idealism in the service of great foreign policy undertakings in peacemaking, human rights, and cooperative problem-solving,” but his “tragedy” was to “bequeath to the twentieth century’s decisive power an elevated foreign policy doctrine unmoored from a sense of history or geopolitics.”

When Kissinger’s account turns to recent and current events, serious weaknesses surface as he uses this analysis as the sole determinant of American foreign policy. The Iraq war, worthy of close examination because it was by far the greatest foreign policy blunder of recent decades, is wrongly portrayed as having been undertaken in pursuit of Bush’s (Wilsonian) Freedom Agenda. While multiple arguments were made by various proponents of the war (ridding the world of a tyrant, bringing democracy to the Middle East, and even improving the chances for an Arab–Israeli peace), the overwhelming case made by the president and his team was that it was the necessary response to the direct threat of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction. National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice’s invocation of the “mushroom cloud” we might see if we did not act was not an offhand remark. The justification of the war as primarily a defense of freedom and democracy came after it turned out that WMDs were not present.

Kissinger’s discussion of the war oscillates awkwardly between an effort to justify it (and his contemporary support for it) and criticism of what the hardheaded Kissinger knows to have been a terribly unwise venture. “I supported the decision to undertake regime change in Iraq. I had doubts…about expanding it to nation building.” Kissinger has warm words for George W. Bush (“I want to express here my continuing respect and personal affection” ) but immediately afterward notes that attempting to advance American values “by military occupation in a part of the world where they had no historical roots,” and expecting “fundamental change” overnight, was unrealistic.

Kissinger’s discussion of the war ends on a particularly weak note with the claim that it’s too soon to judge because the war may eventually be seen to have catalyzed the Arab Spring: “The advent of electoral politics in Iraq in 2004 almost certainly inspired demands for participatory institutions elsewhere in the region.” It is not too soon to know that this view is grasping at straws. The war was almost universally condemned by protest movements and opposition parties across the Arab world. The Iraqi political parties that emerged were largely sectarian, not national, offering exactly the wrong model to others, and in any case they were seen as American creations. Most Arabs saw the war then, as they do today, as an intrusion by the United States that on balance did no clear good and much harm.

The only current issue that World Order treats in depth is Iran’s nuclear program. Kissinger sums up masterfully the years of lying by Iran and ineffective bargaining by the West during which Tehran used the time wasted in bad-faith negotiations to advance its nuclear program. He takes it for granted that nuclear weapons remain Iran’s goal and there are plenty of reasons to do so. But he neglects to mention that US intelligence concluded in 2007, and has reaffirmed twice since, that while Iran continued to enrich uranium in amounts beyond its civilian needs, it had abandoned its weapons program some years earlier.

In fact, we don’t know for certain whether Iran’s government is divided on this point, whether a “threshold” capability (i.e., the technology and fissile material to produce weapons on short notice, like Japan, for example) is the current goal, whether making actual weapons was once the goal and is no longer, or whether it has been the goal throughout. What we know for sure is that Iran has fastened on enrichment as the one thing it won’t give up—as the sign of its technological prowess and the measure of success in its confrontation with the West.

Also weakening his account is the absence of any mention of Iranian public opinion. In the election of 2013 one candidate campaigned explicitly for “an end to extremism” and “flexibility” in reaching a nuclear accommodation. Among six candidates, Hassan Rouhani won just over half of the vote with a 73 percent turnout. The Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, is still the decider and he may not have changed his mind, but he is well aware now that a majority of his countrymen badly want an end to living as international outcasts. In ignoring this, Kissinger goes too far in ruling out the possibility that there has been any significant change in Iranian policy. He warns—rightly—that Iran may simply be showing enough good faith to break the sanctions regime while retaining enough nuclear capability to turn it quickly into a weapons program later.

That is a real risk. But as an experienced strategist, Kissinger should have weighed it against the available alternatives. They are only three. One is to reach an imperfect (because it will be a compromise) deal that requires vigilance and enforcement; a second is to return to the cycle in which more sanctions are followed by more centrifuges, which has brought Iran this far; and the third is war. Any serious examination of the latter reveals costs that far outweigh the benefits of a few years’ delay in what would henceforth be an absolute Iranian determination to get the bomb.

World Order ends where it begins, portraying the American people as dangerously unable to balance national interests and the desire to advance universal values. Public opposition, he believes, hampered or prematurely ended four of the five wars America has fought since World War II (Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq). America’s record is a “tragedy.” It is a country

whose people have been prepared…to send its sons and daughters to remote corners of the world in defense of freedom but whose political system has not been able to muster the same unified and persistent purpose.

Americans are too prone to ignore the strategist’s “unsentimental analysis of underlying factors” (cf. the invasion of Iraq). At least in this telling, though, Kissinger’s own ambivalence is evident as well. What he never describes is what balance he would strike in specific tough cases that the US now faces. Without that, his call for change cannot do much to resolve the perennial ambivalence he deplores.

4.

Both these books deal with the core issues of geopolitics, of war and peace. Neither has much to say about economics, energy and other resources, demographic trends, human well-being, or environmental issues, especially the existential threat from climate change. Kissinger comments in his final pages on what he sees as the negative effects of the Internet and social networks in “destroying privacy” and diminishing “the strength to take lonely decisions.” But the geopolitical lens of his book focuses on where and how states compete. It has little to say either about the expanding groups of issues on which they must collaborate or about powerful, new, nonstate forces.

While the Westphalian system has shaped relations among states for three and a half centuries, and continues to do so, its reign has profoundly changed during just the past two to three decades. Borders, to put it simply, are not what they used to be. In 1648, nearly everything that mattered could be located within a fixed boundary—not so today. The trillions of dollars sloshing around in cyberspace, pollution, globalizing culture, international criminal networks, and the stressed global commons of oceans, air, and biodiversity are all changing the world profoundly. So are tightly knit but nongeographic communities of national diasporas, ethnic groups and violent jihadists, corporations largely unmoored from any one country, and the gigantic global financial market—now almost twice as large as the global GDP.

These limits on global resources, porous borders, a globalizing culture that both fragments and amalgamates, and growing requirements for states to work together for mutual well-being if not survival all mean that today’s world order, and certainly tomorrow’s, cannot be seen only as a matter of the distribution of state power or as a system in which only states matter. The Westphalian order is not going away, but it is no longer what it once was. It’s too soon to see what that system and the new forces will produce as they co-exist; but it’s safe to say it won’t look anything like the familiar past.

This Issue

March 19, 2015

Can They Crush Obamacare?

2016: The Republicans Write