Taking as his subject the transformation in the treatment of criminals that occurred in Britain between 1750 and 1850, Michael Ignatieff has made a real contribution to the growing literature that deals with the emergence of penitentiaries as “total institutions” of incarceration. While Michel Foucault, for instance, has illuminated the subject with the brilliant speculations of Discipline and Punish (1978), Ignatieff undertakes the no less essential task of uncovering the historical facts behind the shift in attitudes, and from these he constructs an interesting story.

At the very heart of the effort to free criminal justice from the arbitrary physical brutality of earlier ages there was a basic contradiction: although the major thinkers of the reform movement reached the same conclusions, they did so from opposite points of view. Thus, John Howard, the “father of the penitentiary,” was a devout Nonconformist, while Jeremy Bentham, the leader of the Philosophical Radicals, was an agnostic utilitarian and a crude materialist. Nevertheless, the goal these men pursued was the same, the establishment of a system of complete discipline aimed at changing and reforming criminals, and, as Ignatieff demonstrates, it mattered little in the end whether that idea was rooted in notions of religious asceticism or based upon Bentham’s psychological calculus.

Their crusade to harmonize “the imperatives of deterrence” with “those of humanity” bore its inevitable fruit in the ghastly routines of Pentonville prison, opened in 1842, where the humane ideals of early reformers survived only in the daily sermons delivered to men broken on the wheel of inhuman solitude, ceaseless drudgery, and faceless discipline. But while quite able to trace the historical path of these developments, Ignatieff is weaker when it comes to explaining the changes. He simply uses the jargon of class warfare without carefully discussing its applicability. Treating the major reformers only as tacticians in the ongoing suppression of the working class, Ignatieff fails to consider them as representatives of a general movement toward central control. And, in blandly concluding that penitentiaries are and have been the result of society’s inability to tolerate deviance, he leaves it to the reader somehow to square this platitude with the complex and terrifying reality of violent and antisocial behavior.

This military history is more than a straightforward narrative combining intermittent injections of political analysis and illuminating personality sketches with quantitative assessments of the protagonists’ personnel, arms, strategies, and maneuvers in the Middle East conflict. Dupuy, author of numerous military histories, draws on the conventional printed sources, embellishing and correcting inconsistencies through personal interviews with Arabs, Israelis, and UN officers to provide a descriptive account of the Arab-Israeli wars of 1947-1949, 1956 (Suez), 1967, 1967-1970 (the War of Attrition), and 1973. Although adding little to the 1947-1949 period, in emphasizing the wars from 1967 on—a third of the volume is devoted to the October War—and comparing 1967 and 1973, Dupuy provides an informed comparison of tactics, objectives, victories, and failures in the two conflicts.

He dispels a number of myths: Arab soldiers fought well in many battles in the Sinai during the 1967 war but were precipitously ordered to withdraw by Egyptian Field Marshal Amer, thus inadvertently assisting the speedy Israeli advance to the Canal; Syrian and Egyptian commands did unite to plan the formidable surprise attack of 1973, and Dupuy gives no evidence they had Russian assistance in doing so; and, although the Arabs far outnumber the Israelis, the relative strengths of operational armies in each of the wars has been less than two-to-one. In the last analysis, it was not the Arab soldier but—until the October War—political military appointees, bad judgment, internecine quarreling, and poor military training pitted against an increasing Israeli combat effectiveness which created a situation of thirty years’ armed truce in the area. Dupuy’s description is absorbing and his factual compendium a useful guide to the military realities of the Middle East.

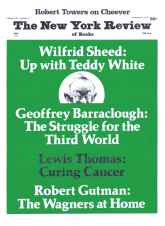

This Issue

November 9, 1978