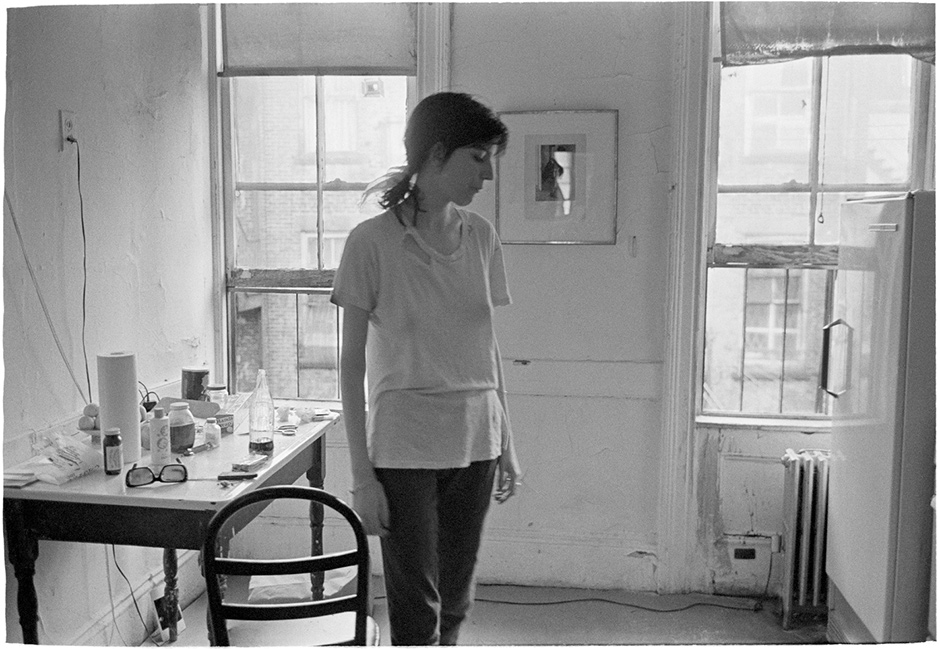

Patti Smith has published a new book, M Train—a work whose charm has much to do with its lithe resistance to the constrictions of any particular genre—as her earlier Just Kids (2010), her memoir of her early partnership with Robert Mapplethorpe, continues to exercise a lively influence. Even before Showtime announced over the summer that it would be the basis for a TV miniseries, it was clear that Just Kids was sending down roots in the culture. For younger readers it serves as an irresistible window into the New York era of the late 1960s and early 1970s, what with a supporting cast including Janis Joplin, William S. Burroughs, Andy Warhol, Jimi Hendrix, and Allen Ginsberg, set against such backdrops as Max’s Kansas City and the Chelsea Hotel. But I suspect that beyond adding another layer to the collective legend of that period, it will take its place as one of those durable books that people turn to for an object lesson, a demonstration of possibilities, on how to make a beginning in life.

In recounting how Smith and Mapplethorpe fled the prospect of narrow futures (she escaping soul-crushing factory work in southern New Jersey and he the limits of a rigidly Catholic family in Floral Park, Long Island) and scrounged out independent artistic lives for themselves in New York City, Just Kids relives the bedeviling confusion and panic of starting from zero—zero resources and zero encouragement—and attempting to make a life one can call one’s own. To invoke the vulnerability and magical destinies of fairy-tale characters—“We were as Hansel and Gretel and we ventured out into the black forest of the world,” Smith writes of herself and Mapplethorpe—is to reenter the eddy of uncertainty that the young know well yet so often, once settled in life, tend to smooth over in memory. In Smith’s pages that swirl becomes a new encapsulation of an old romantic ideal, in the image of the young couple who nourish each other’s artistic energies. It is like the resurrection of a discarded dream: that hermetic religion of art in which love transcends itself in a magnificent consuming alchemy to yield selfless art on the far end of its grueling process.

For latecomers such romanticism is tinged with the exoticism of a city that no longer exists, a world of lost possibilities where a low-rent marginal existence was possible if not necessarily comfortable, a city for scavengers where ghostly daguerreotypes and talismanic religious objects might be retrieved from the unlikeliest shelves and street corner bundles, and where, in the absence of MFA programs and other well-organized channels for the creative process, those just starting out were obliged to make things up for themselves, relying on whatever tutelary guides they were fortunate enough to encounter. When Smith writes of herself at the outset of her artistic odyssey that “Rimbaud held the keys to a mystical language that I devoured even as I could not fully decipher it,” she speaks for several generations of seekers who found their way to the photograph on the cover of the old New Directions edition of Illuminations as if to an icon set up for their guidance alone. When they meet, Smith and Mapplethorpe are artists who have not yet found their art, and the heart of the narrative is the thoroughly unprogrammed way in which they make their way toward the specific practices through which they will realize themselves.

What the book expresses supremely well is the tentativeness of every movement forward, the sense of following a path so risky, so sketchily perceptible, that at any moment one might go astray and never be heard from again, never perhaps even hear from the deepest part of oneself again. For a book that ends in success, it is acutely sensitive to that abyss of failure that haunts the attempt to become any kind of artist. In reading it I was irresistibly reminded not so much of career triumphs as of all the others who were just as much a part of the New York that Smith evokes so persuasively, the crowd of aspirants who likewise sought to become painters, actors, dancers, poets, photographers, songwriters, filmmakers, novelists, or practitioners of some hybrid art form not yet imagined: the ones who stopped, or died, or lost their way, or drifted into one kind of silence or another. I close my eyes and see fantastic canvases populated by winged creatures and devouring disembodied maws, hear shapeless extended guitar solos that sought to describe the creation of the cosmos, screen miles of unedited footage from dream movies destined never to be finished.

Just Kids is a story of success, not failure, as it progresses toward Mapplethorpe’s wide recognition for a photographic mode seamlessly fusing his aesthetic, religious, and sexual obsessions, and Patti Smith’s unforeseeable emergence as a new kind of rock star for whom doo-wop and symbolist poetry, three-chord anthems and Burroughsian apocalypses just naturally went together. Smith elides the triumphal aspect, however, and the book ends somberly as she recounts Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS and mourns him in a series of memorial poems: “Every chasm entered/Every story wound/And wild leaves are falling/Falling to the ground.”

Advertisement

I remember hearing of Smith first as a neighborhood rumor and then, by the time she was performing widely, a local legend who managed to combine the roles of poet, visual artist, and rock and roller, a skeletally thin black-clad androgynous merging of Rimbaud and Pirate Jenny, or of Irma Vep and one of William Burroughs’s Wild Boys.* When it came out in 1975, Smith’s first album, Horses, caught the ear with the rough edges of a homegrown vatic protopunk utterance right from the opening track with its declaration that “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine” and its reworking of Van Morrison’s “Gloria”—“Oh I put my spell on her here she comes/Walking down the street here she comes/Coming through my door here she comes/Crawling up my stair here she comes”—to assert that rock and roll really did belong to anybody with the nerve to transform it into whatever sort of poetry she desired. Delicacy of execution was not the issue, but unwavering insistence, prophetic identity. What lingered was not so much musical structures as the indelibility of certain cries, like the refrain, in the suicide dirge “Redondo Beach,” that sounded like the anguished transmutation of a chorus from a Top 40 hit of the girl-group era: “are you gone gone.”

The shamanic impulse—invocation of spirits, channeling of the voices of dead poets, prayer to unknown forces—pulses through the three hundred pages or so of Smith’s Collected Lyrics, 1970–2015, even if the texture and tenor lost some of their early ferocity as she went from local legend to authentic rock star to a kind of transnational cultural ambassador. As the years go by, the coded transmissions all the more potent for their partial obscurity—“You know I see it written across the sky/People rising from the highway/And war war is the battle cry/And it’s wild wild wild” (“Ask the Angels,” 1977)—give way to more clearly decipherable global messages on, say, the Iraq War: “Your bombs/You sent them down on our city/Shock and awe/Like some crazy t.v. show.” Having a worldwide audience must make it hard to retreat into those secret spaces that are so readily available to the young artist not yet known.

I had begun to lose track of Patti Smith’s music as my ears took me in other directions, so that increasingly I heard her if at all from another room or as background, on someone else’s radio or turntable. Thus I was not so acutely aware that at the beginning of the 1980s she had largely left the music scene, gotten married (to guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith of MC5), moved to Detroit, and raised two children. After her husband’s sudden death in 1994, she resumed an active career of recording and touring, and in decades since has been most visible, whether exhibiting her art at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, accepting induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, or appearing briefly in Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme, not to mention a cameo on the TV series Law and Order: Criminal Intent.

Of all that activity she has little to say in M Train. In fact the book opens with the declaration: “It’s not so easy writing about nothing.” The words are spoken by a dream cowboy, establishing from the start a freedom in moving in and out of frames, and in speaking from within a private space. Everything that happens, at first, seems intended to stake out a zone far removed from performance or public life, as if she were murmuring to herself, while she slips into a coat and walks over to a café on Bedford Street, reiterating: “I’m sure I could write endlessly about nothing. If only I had nothing to say.” The season is dark and autumnal, the café is empty in the early morning, she drinks the black coffee that will permeate the book as if the idea of that aroma were a necessary ritual to sustain a link with language.

M Train might be taken as a most roundabout and leisurely way of answering the question “How have you been?” The answer comes in the form of fragments of waking fantasy, literary commentaries, extended reminiscences, evocations of lost objects, travel notations, tallies of places and names and flavors (“Lists. Small anchors in the swirl of transmitted waves, reverie, and saxophone solos”). By turns it is daybook, dreambook, commonplace book. Under all lies a grief that is never allowed to overwhelm the writing but is, it would seem, its groundwater. She allows herself to begin anywhere and break off anywhere, thus realizing the secret yearning of almost anyone who sits down to write a book: that it might be possible for the thing simply to create itself out of necessity, to emerge as if by a natural process of unfolding.

Advertisement

It is in its way an obsessively literary book: “Writers and their process. Writers and their books. I cannot assume the reader will be familiar with them all, but in the end is the reader familiar with me? Does the reader wish to be so?” Most of the time she is in conversation with a myriad of other books, some familiar contemporaries (Bolaño, Murakami, Sebald, Aira), some primordial influences (Genet, Bowles, Brecht, Burroughs, and of course Rimbaud), and some from a shelf of childhood favorites, The Little Lame Prince, Anne of Green Gables, A Girl of the Limberlost. To write is to be in the presence of books: “I prefer to work from my bed, as if I’m a convalescent in a Robert Louis Stevenson poem.” This Stevenson reference echoes a line in Just Kids, where she invokes A Child’s Garden of Verses in connection with a long period of childhood illness.

The recurrence of the image triggered for this reader at least a powerful recollection of the 1944 edition of A Child’s Garden that was almost my first reading matter, illustrated by Toni Frissell with photographs that included, to accompany “The Land of Counterpane,” an unforgettable image of a sick child—his face a study in unworldly absorption—propped up in bed, studying the toy soldiers he has deployed on the bedcover. Whether or not Patti Smith was reading Stevenson in that same edition, she had certainly touched me on the level of the deepest readerly associations. That indeed was reading: that earliest awe of communing with words and images before even knowing what “words” and “images” might be, of forging a sense of community with beings that the words and images made shimmeringly half-present. To touch on such experiences, to insist on the primacy of those private worlds, is an intimate sort of whisper, an ultimate indulgence, seeking no wider justification. The pleasure of the book is inseparable from that indulgence.

With no sense of pastiche or irony she lets herself write in a language sprung from old books, of “a looming continuum of calamitous skies…a light yet lingering malaise…a fascination for melancholia.” In London, the Nelson column and Kensington Gardens are “all disappearing into the silvered atmosphere of an interminable fairy tale,” as she travels by taxi through thick fog “flanked by the shivering outline of trees, as if hastily sketched by the posthumous hand of Arthur Rackham.” We are back among mist-haunted decadents and symbolists, back among the artifacts of everything long ago left behind that yet insists on surging up once again, in an inscape of reverie drawing on any usable association from any available epoch.

When the modern world intrudes it seems already a ghost of itself. In a moment of extreme disorientation the words that emerge from the void are from the Clovers’ “Love Potion #9”—“I didn’t know if it was day or night”—as if they were from a mystical treatise by Jakob Boehme. Moving from one solitary room to another, from New York to Berlin to London to Tokyo, she tunes in to an array of TV crime shows, whether American or British or Swedish, whose protagonists in turn become part of her syncretistic pantheon.

The ghostly presences may be mute objects: her father’s chair, which she never sits in, but whose “cigarette burn scarring the seat gives the chair a feel of life,” or a lost black coat, a gift from an older poet, whose disappearance is repeatedly mourned: “The dead speak. We have forgotten how to listen. Have you seen my coat?” Rituals establishing links with the dead and disappeared are almost the bass pattern here. In a long episode early in the book Smith recounts how she and her husband traveled, on their first anniversary, to French Guiana to visit the ruins of the penal colony where convicts were held for transfer to Devil’s Island, a visit inspired by Jean Genet’s description of the place in The Thief’s Journal as “hallowed ground” associated with “a hierarchy of inviolable criminality, a manly saintliness that flowered at its crown in the terrible reaches of French Guiana.”

Genet was still alive at the time and the intention was to bring him a box of earth and stone gathered from the site. This did not come to pass, but in keeping with her sense of ritual obligation Smith travels in Morocco to Genet’s grave in the fishing port of Larache. A Polaroid of the occasion is included in M Train, one of a series of photographs extending such observances—pilgrimages to the graves of Sylvia Plath or Yukio Mishima, or to contemplate the crutches of Frida Kahlo or the walking stick of Virginia Woolf—by another form of memorial preservation. Preservation is counterbalanced of course by the march of disappearance, a disappearance that outstrips Smith’s own book. When her favorite café closes she takes her morning cup at Caffè Dante on MacDougal Street, itself closed down since her book was written, and in Tokyo stays at the Hotel Okura, a modernist monument imminently slated for demolition.

If the book represents a sort of negotiation (through rites of pilgrimage and writing and art and divination by tarot card) with the implacable forces of the world, the world finds its way into the book through nonnegotiable devastation. Smith buys a house on Rockaway Beach only to see the beach take the full brunt of Hurricane Sandy. On her visit to Japan she witnesses the aftermath of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami: “The rice fields, now unyielding, were covered with close to a million fish carcasses, a rotting stench that hung in the air for months.” These catastrophes set a contrary wind sweeping through the inward consciousness she cultivates in the pages of M Train. They serve as a brutal wake-up from what can begin to seem like relentless spiraling into a private world.

What rescues the book from that self-absorption—from the amorphous groping of sentences like “I wondered if it was possible to devise a new kind of thinking” or “In my way of thinking, anything is possible”—is its unapologetic informality. “I have lived in my own book,” she writes toward the end, and it is hard to argue with that. It’s a bit like the title of the old Bill Evans album: Conversations with Myself. Or, in its quality of simply laying out the contents of one’s mind to see what they look like, that altogether different book by George Gissing, The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft.

Perhaps M Train represents the attempt by someone whose career is as public as can be imagined to stake out a zone of inviolable privacy, albeit through the public act of writing a book meant for publication. That paradox, of a solitude played out in plain view, plays about the edges of M Train but does not overwhelm it. Writing about nothing is after all one of the most ancient and gratifying of literary practices, often so much more rewarding than more formal chronicles and autobiographies and for that reason something that always feels a bit illicit.

This Issue

October 22, 2015

The Very Great Alexander von Humboldt

The Terrible Flight from the Killing

-

*

For a detailed account of Smith’s early performing career, see Luc Sante, “The Mother Courage of Rock,” The New York Review, February 9, 2012. ↩