A month and a half after the opening of its new building, the Whitney Museum is now hosting an eleven-day festival celebrating the work of American expatriate composer Conlon Nancarrow, whose innovative and complex studies for player piano drew on styles as disparate as jazz and serialism, and made use of multiple tempos played simultaneously.

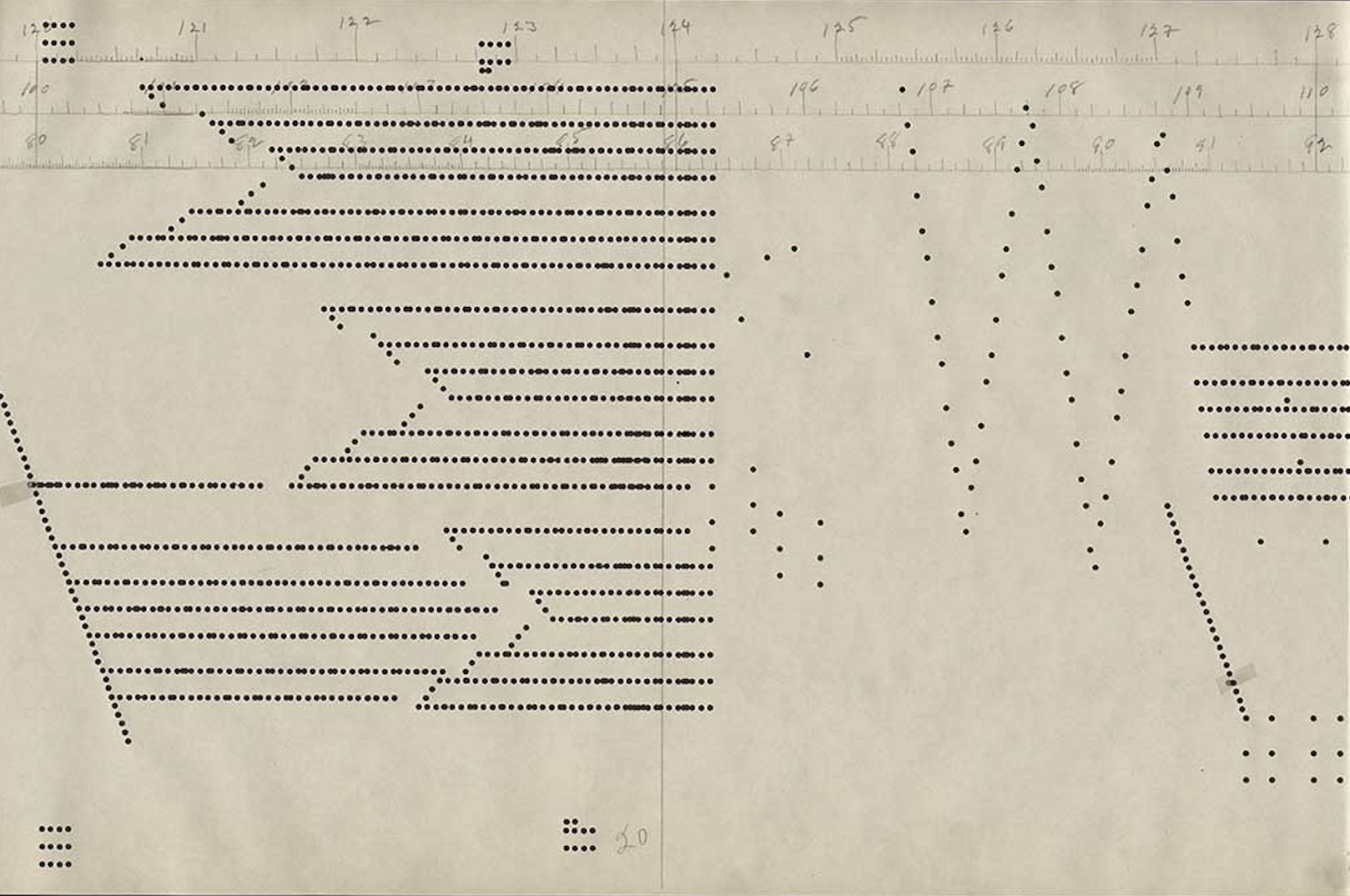

Nancarrow’s interest in the player piano arose partly out of necessity, as there was a scarcity of conservatory-trained musicians in Mexico City, where he lived for decades in self-imposed exile until his death in 1993. But even before he left the United States in 1940, he was drawn to the technical possibilities of the machine, which can play faster and with greater precision than the most virtuosic pianist. Nancarrow explored the limits of the player piano with staggering imagination and persistence, diligently punching piano rolls by hand and often with the aid of a magnifying glass. He lived in obscurity and near-isolation for many years before his work was championed by prominent composers such as the Hungarian experimentalist György Ligeti, who claimed that Nancarrow was the most important composer of the late twentieth century. Only after his fame grew did Nancarrow again write works—still highly demanding—for human musicians.

Born in 1912 in Texarkana, Nancarrow played trumpet in jazz bands during his youth. He studied composition in Boston with Roger Sessions, who helped popularize European modernism in America, and the neoclassicist Walter Piston, whose other students included Elliott Carter and Leonard Bernstein. Drawn to Communism while in Boston, Nancarrow later joined the Republican Army during the Spanish Civil War and, upon his return to the US, was unable to get his passport renewed because of his political beliefs. He settled in Mexico City instead and there began his work for player piano.

These pioneering studies, which anticipated the development of computer-generated music, draw on and mix together a variety of musical techniques—including boogie-woogie, the rapid runs of jazz pianist Art Tatum, serialism, and “chance constructions” inspired by John Cage, a friend of Nancarrow’s. But their most intriguing feature is their use of the mensural canon. In more common canons, one voice imitates another after some delay. (The most recognizable form of a canon is a round, such as “Frère Jacques” or “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” in which a voice begins the melody two bars after the preceding voice.) In mensural canons, however, one voice follows another in a different tempo. Listening to a mensural canon can be disorienting, because the voices, moving at different speeds, may sound as if they belong to entirely different compositions.

The relation between tempos in the studies grew increasingly abstract as Nancarrow aged. In the early Study #14, for example, the tempo ratio is 4:5. In other words, the second voice is played at a speed 25 percent faster than the first. (Because player pianos can be set at different speeds, the ratios are not objective tempo markings; they refer to the relation between the physical space taken up on the piano roll itself by a distinct rhythmical value in each voice. The space between two quarter notes in the second voice will be 25 percent longer than that in the first voice.) In Study #40b, created for two player pianos, the tempo ratio is e:π (approximately 2.72:3.14). The two instruments play the same piece, but the second enters later than the first and at a faster tempo, such that they end together. The tempo ratio in the twelve-voice Study #37 is 150:160 5⁄7:168 3⁄4:180:187 1⁄2:200:210:225:240:250:262 1⁄2:281 1⁄4, which is derived from the frequencies of notes in a chromatic scale.

While the geometric precision of Nancarrow’s works inspires awe, the ear can’t discern such complex relationships, and human performance is in most cases impossible. Many of the studies move at a lightning pace and are so dense that listeners can only hope to pick out a snatch of melody before another intrudes, or to identify a few pulses of one tempo before another engulfs it.

To balance the rhythmic complexity of his work, Nancarrow often based his pieces on simple, if unusual, melodic ideas, such as vigorous glissandi and repeating units of notes. He believed, as he told one interviewer, that if the voices have “the same melody, you don’t have to follow the melody. You’re just hearing the temporal relationship.” Indeed, when the voices share themes and motives, the most startling combinations of tempos possess a unifying logic. But even when you don’t understand what you’re hearing, the sheer energy of Nancarrow’s inventions can be delightful, and watching the piano rolls unfurl provides its own pleasure.

Study for Player Piano #3a

Inspired by boogie-woogie piano and played at a breakneck speed, Study #3a is perhaps Nancarrow’s best-known work. A bass line, which repeats over a blues form, is layered with disjointed melodies and interjecting chords.

Advertisement

Study for Player Piano #7

Along with his other innovations, Nancarrow revived the medieval musical technique of isorhythm, which is the use of different pitches over a repeating rhythmic pattern. Here, Nancarrow layers isorhythms on top of one another and displays his rich harmonic knowledge. The structure of Study #7 resembles the classical sonata form.

Study for Player Piano #21—Canon X

Canon X is so named because the faster, higher voice decelerates as the slower, lower voice accelerates. The two voices play at the same tempo for a brief moment in the middle of the piece, and each ends in the tempo in which the other began. Despite the atonal and seemingly illogical melodic lines, the piece ends in a perfect cadence, giving it a sense of finality.

Study for Player Piano #36—Canon 17/18/19/20

This piece features four voices playing the same melodic line not only at different tempos, but also transposed to different octaves and keys. The first, slowest line begins first but ends last.

Study for Player Piano #46

In his last studies, Nancarrow masterfully combined his previous techniques. Study #46 is a mensural canon built on an isorhythm that creates a feeling of acceleration as the three voices (in the temporal ratio 3:4:5) converge.

Anywhere in Time takes place at the Whitney from June 17 to June 28. For more information, visit whitney.org.