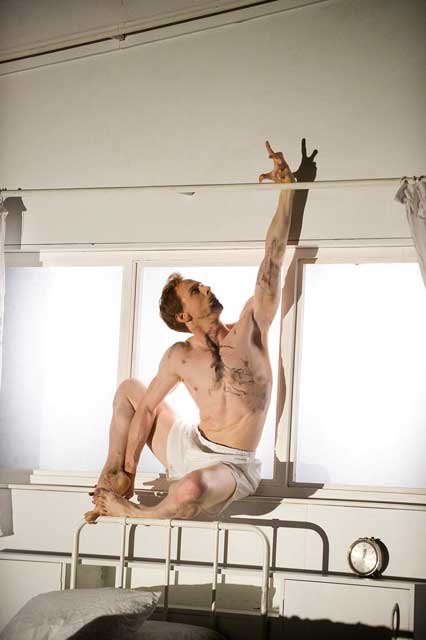

Edward Watson’s performance as Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis shows how thin the line between the beautiful and the grotesque can be in ballet. Watson, a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet, has danced the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, Rudolf in Mayerling and next year will dance Romeo in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet. In this adaptation of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis by Arthur Pita, Watson evokes the nightmarish experience Kafka describes—of a man who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a giant insect—through the vocabulary of ballet. Here you can see his leg turned out at the hip and his foot arched. But what he is doing with his toes makes the whole posture hideous. They wriggle like a millipede’s legs, as though beyond his control, and Watson looks at them in horror.

Watson has developed a wide range in this idiom. The role was choreographed on him: he makes his acutely articulated muscles look like arthropodic armor, and he has said that he has a tendency to “stretch things” so that they “don’t look right” in classical ballets. Yes, there is disgust and fear, but he also shows compassion toward his family, which is more than they show him. Despite his redeeming qualities, Gregor and his surroundings only get more squalid. Once he starts to get used to the idea of being an insect, the set, designed by Simon Daw, tilts up and backwards, so that he can scurry up the walls. Soon, brown gunge starts to spread over the white walls, the bedclothes, and the dancers.

The set design challenges the audience not to look away. The stage is split in half, with Gregor’s room on one side, and the 1950s family kitchen on the other side, where his mother, father and sister try to continue as normal. During one of Gregor’s most contorted episodes, the focus is on his sister Grete, danced by Corey Annand, who is in the more brightly lit kitchen, performing barre exercises. It should be disturbing and it is, with an unsettling score by Frank Moon. But not unrelentingly so: before a final crisis, there is relief in a Jewish folk dance, led by the family’s three lodgers.

This production is mounted by the Royal Ballet but it is described as a “dance theater adaptation”, and most of the roles involve more acting than dancing. (Although there is not much in the way of dialogue, occasionally the characters cry out in Czech. More often they scream.) Yet Pita’s Metamorphosis is much concerned with ballet and ambivalent about it. Grete aspires to be not a violinist, as she does in Kafka, but a ballet dancer. Her character develops in the opposite direction to her brother’s. As Gregor is more and more dehumanized, we see Grete progressing from an attempted pirouette in her school uniform, to her first ballet slippers, to pointe shoes. Whether her transformation is desirable is an open question, but the final moments of the performance suggest that it might not be. On the day of Gregor’s funeral, the family gathers in front of his window at dawn and a music box plays, while Grete lifts her arms and turns slowly like a mechanical ballerina—purged of the sorts of movements we have seen Watson perform and more besides.

Selections from Frank Moon’s score for The Metamorphosis

Bev Lee Harling sings in Czech, the language used on stage throughout. The song precedes a dream sequence, during which two other insect-like dancers smear slime over Gregor’s body.

Gregor’s mother, father and sister join their three lodgers in a folk dance, which ends abruptly when Gregor tries to join in and the lodgers see him for the first time.

This theme plays in the funeral scene, and accompanies a hand-cranked music box that takes paper strips. The music box is operated live and cannot be heard on the recording.