There’s a moment in Adelle Waldman’s new novel, Help Wanted, that delivers a sharp comment on the status of literature in a culture gripped by app-enabled conspicuous consumption and next-day delivery. The novel is set in the warehouse of a big-box store, where each morning a group of nine workers clocks in before dawn to wrangle the endless flow of goods and the accompanying detritus of pallets, Styrofoam, and ever more cardboard. One by one boxes of tiki torches, mini gas grills, pool noodles, DVDs, and luxury quilted toilet paper fly from the truck. Finally the workers reach their last, sad package:

Short and squat with red stripes on its sides—it contained books, from the publisher Penguin Random House—the last box seemed, in proportion to the number of eyes that turned to look at it, almost comically insignificant, like a limp penis overpowered by pubic hair.

When people are wrecking their backs lugging packages for minimum wage and no benefits, what’s the point of another literary novel?

This is quite an about-face for Waldman. Her debut, The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. (2013), was celebrated for its immersion in the pretensions and self-deceptions of a certain species of literary Brooklynite, the kind of emotionally ruthless aspiring writer whose major work is his good guy persona. For Waldman and her contemporaries, the imperative to write what you know often meant turning a keen eye on insecure creative types, from Ben Lerner’s anxious poets to Elif Batuman’s philosophical undergrads. A frequent criticism of such works is that they are too insular, more curious about their own social rituals than the world beyond. But their look inward is also a strength: when writers make good protagonists, it is not because their jobs are the most interesting but because they are the characters most immediately available for study, the nearest targets for shrewd dissection and psychological portrait.

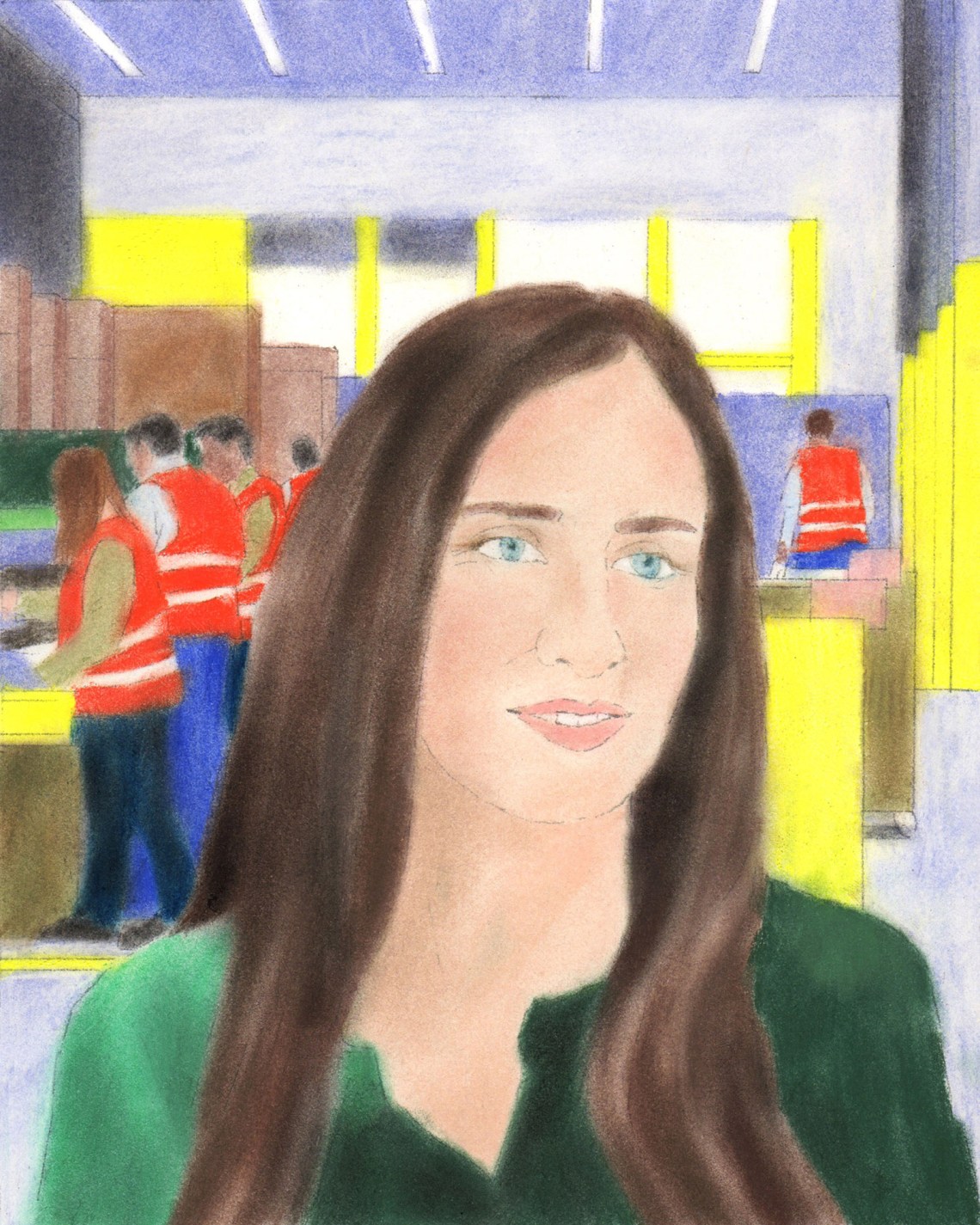

In the years that followed Nathaniel P., Waldman entertained doubts about this intense inward focus, namely that it does not serve a clear social justice agenda. “I love nineteenth-century novels and used to think like Jane Austen that writing about the romantic and psychological problems of middle-class people was a valid way to spend a career,” she recently told Publishers Weekly. Then “the 2016 election happened and it jolted me.” She felt she had not paid attention to the major social forces that were shifting the direction of the country. She went to work at a big-box store near her home in Rhinebeck, New York, for six months as a form of research. And though she expected the job to be demanding, she emerged, she recently wrote in a New York Times op-ed, appalled by “the subtler and more insidious” ways she saw corporations mistreat their employees.

From this set of observations she might have compiled an exposé of low-wage work in the vein of Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed (2001) or, more recently, Emily Guendelsberger’s On the Clock (2019). And indeed Waldman’s novel shares many of the features of these books, packed as it is with details about scheduling, employer-provided benefits and the lack thereof, nonsensical corporate policy, and the minimal opportunities for initiative and self-expression in the American workplace. But Help Wanted is also an attempt to imagine the inner life of the warehouse in fiction—a bet that it’s possible to draw out the fleeting interplay of habits, aspirations, and disappointments in her characters mainly by sketching their working conditions.

One of the challenges of writing a social novel set almost entirely in a warehouse is that the characters do not have much time to talk to one another. At this fictional superstore (which is named Town Square but sounds a lot like Target), the warehouse shift starts at 4:00 AM with a frantic race to meet the “unload time” set by corporate; everything must be off the delivery truck by 5:00 AM, or a manager has to send a “failure report” to the higher-ups. The workers spend the rest of their shift breaking down the deliveries, unpacking and setting them up on the shelves and displays of the shop floor. They rarely have a chance to make consequential decisions together—to debate or plan anything. They are scolded if they try anything new and labor under the constant threat of getting written up.

When Help Wanted opens, however, the employees of Town Square Store #1512 have a special reason to huddle during their breaks. They learn that the store manager, Big Will, is leaving the fictional Potterstown, a depressed small city in the Hudson Valley, for a store in affluent suburban Connecticut. His departure creates a vacancy. An obvious candidate for the job is Meredith, the executive manager of the warehouse, whom everyone hates. But an executive manager in sales, Anita, “who no one loves but no one hates either,” also has a serious chance. Ordinarily such a decision would be made over the heads of the rank and file, in a glass cubicle far away. But in this case the company wants to move quickly: instead of conducting an open job search, which could take months, they plan on promoting an internal candidate. And in an unusual extra step they decide to send a few executives to interview the store employees about the frontrunners.

Advertisement

The workers on Meredith’s team have every reason to sink her candidacy. She’s often out of her depth, intimidated by the longtime employees who know more about warehouse operations than she does, and she is too proud to ask for their help. Insecure about her precarious authority, she compensates by giving high-handed orders and sometimes resorts to cruel mockery of her subordinates. She insults an employee (“she’d called Nicole ‘slow,’ as in retarded, and imitated the supposedly imbecilic expression on Nicole’s face”) and then threatens to discipline her for her “bad attitude.”

The workers also hate Meredith because she represents the worst of corporate culture. Town Square is the kind of company that is willing “to cheat employees in any way that was technically not illegal (and call it ‘performing its fiduciary duty to stockholders’).” Cutting hours and staffing levels are time-honored strategies. Big Will reminisces that when he started, the store had twice the number of employees. Nothing runs as smoothly as it used to, as customers often complain. The store prominently displays “help wanted” signs, as if to suggest that they are always just a few new hires away from getting up to speed—if only they could get the staff. The real problem, the sign implies, is “the tight labor market and/or a lazy populace’s unwillingness to work service jobs.” And worse, Town Square is far from the toughest employer. It’s better than Walmart and better than the conspicuously unnamed “online retailer” that has eaten into a large portion of its market.

Meredith is simply the most proximate spokeswoman for this woeful economy. She wields management jargon like “Smart Huddle” and “mandate” to justify stupid decisions. She refuses to give her team extra hours even when her deputy, Little Will (who is taller but lower-ranking than Big Will), informs her that they’re so shorthanded that whole sections of the store are sitting empty—at a potential cost of thousands of dollars a day. Judging that corporate will reward her solely for staying on budget, not for maximizing revenue—which is someone else’s responsibility—she refuses. “That means working harder and smarter with the hours we have,” she decrees. Never mind that Diego’s phone has been cut off because he can’t pay the bill on less than twenty hours a week. Meredith is impervious to guilt. “Wasn’t this what welfare, Medicaid, food stamps, etc., were for?”

Yet this isn’t a novel about a set of disgruntled workers airing heartfelt grievances about their boss. Because instead of voicing their true feelings about Meredith, the employees decide to try to get her promoted.

This twist is what sets the novel in motion and allows Waldman to imagine each of her characters breaking out of their routines to make a series of subtle calculations: weighing their own prospects against Meredith’s, estimating their chances at Town Square and their chances in Potterstown.

The idea comes from Val, a woman in her late twenties with strong convictions who is often the first to speak her mind. She has a habit of hiding the offensive T-shirts the store sells (those with “camouflage backgrounds and images of guns”) and placing nicer ones (with slogans like “Be Kind” and “Wine Mom”) in front of them. Her pitch to her coworkers is this: if Meredith got the promotion, she’d no longer be managing them directly. Little Will, who is widely respected and has always stood up for the others, would likely get her position. And Little Will’s promotion from group manager to executive would open up a vacancy at the most junior level of management, a rung on the ladder that could be just within reach for someone like Val or one of the others.

In short, while Meredith’s promotion would bring her an unjust reward, it would improve everyone else’s lives to some extent. Jobs with benefits and above-minimum-wage pay for people who do not have a college degree are exceedingly rare in Potterstown, a city hollowed out by deindustrialization. If Meredith and Little Will stay in their current positions, it may be years before a similar opportunity arises. During this time most of the team would continue to contend with the many and varied problems of scraping by—not just the creeping despair (“some invisible mechanism ensured that when one source of unhappiness lifted, another fell,” a worker thinks) but the practicalities of paying for medical treatment and childcare and getting to the store without a car. (Diego walks to work in the dark, along a treacherous highway that has no sidewalk.)

Advertisement

One of the pleasures of Help Wanted is seeing this realization sink in for each member of the team. This is a novel that distinctly avoids having a main character, neither the charismatic Big Will nor the villainous Meredith, and though Val is something of a ringleader Waldman devotes a roughly equal amount of space to each of Val’s eight coworkers, whose names appear in a line at the bottom of the org chart. The narrative hierarchy is, like the hierarchy among these nine workers, flat. There’s Diego, who muses that if he could get the group manager job, he would finally be able to show the “regular, predictable income” needed for a car loan; Ruby, who doesn’t really care what ultimately happens but shows up for the meetings because it adds some variety to her day; Nicole, the strongest holdout against the plan, who resists it owing to her “instinctual, moral” conviction that Meredith should be punished, not promoted; and Milo, and Joyce, and Travis, and Raymond, and Callie.

The plot is notably light on moments of high drama—no extravagant meltdowns or shop floor injuries. (An air of light industrial menace is often present, as when “every few seconds, high pitched squeals tore through the dark space”—though it turns out the sounds are not human screams but tracks that need to be oiled.) The book’s interest is in following each character’s train of thought as they work, pondering their lives up to this point and what they might be able to change. The main action takes the form of secretive meetings during smoke breaks and carefully planned one-on-ones, as Val and her faction (who label themselves “pro-Mer,” short for “promoting Meredith”) attempt to recruit the others to their cause.

The trick of this plot is that the excitement that builds around the campaign creates a heady sense of forward motion, until the same excitement becomes the novel’s saddest feature. The sheer amount of energy expended on bringing about such a small improvement underlines just how limited the workers’ options are. The pleasure of using their new skills—to develop and strategize and win support for a course of action—only emphasizes how much talent and ability are going to waste at a workplace that punishes employees when they show initiative.

It’s also hard not to sense a union plot haunting Help Wanted. The workers repeatedly show their capacity for collective action, yet the pro-Mer campaign only ever aims to exchange one boss for another, not to bring about a permanent change in the terms of their employment, as a union would. The anticlimax isn’t lost on Nicole when the campaign is over and she feels “a little wistful…for what things had been like only a few weeks ago.” Instead of heralding a transformation in the workplace, Waldman traces a subtler story of the deftness of corporate union avoidance and the staff’s unanimous resignation to these tactics: the faintest mention of forming a union draws grim laughter among the workers. “Don’t even joke. Then we’d really be in trouble,” Ruby warns. They’ve seen an employee fired “for ‘time theft’ after he’d been spotted talking briefly to a union organizer during his shift.” A very nice executive named Katherine has taken care to lay out corporate’s position on unions “in friendly, upbeat terms,” accompanied by pizza parties at a store where “organizers were afoot.” She calls her approach the “well-crafted carrot.” The stick goes without saying.

As you can probably tell by now, it’s hard to miss the political points that Help Wanted sets out to make. At its core, the novel is an impassioned case that the people of store #1512 deserve not just better working conditions but also better provision of health care and housing, and better access to education and freedom from debt. But it becomes clear, as the pro-Mer campaign gains traction, that Waldman places more emphasis on intricate systems—whether the corporate structure of Town Square or the machinery of the employees’ scheme—than on a set of equally intricate characters.

When Waldman fills out each worker’s backstory she tends to focus on how they have run up against yet another systemic problem. There’s Raymond, whose girlfriend is addicted to pain pills and steals the money earmarked for their electric bill; Ruby, who has been disguising the fact that she cannot read, a difficulty that may go back to childhood lead poisoning; Nicole, whose “food stamp card hadn’t refreshed at the beginning of the month like it was supposed to.” There’s nothing wrong with these details per se, and a novel that is attempting to capture a broad sweep of life surely has to acknowledge at least some of them—except that the characters who experience them never quite come to life. If literature can deliver flashes of recognition, here we recognize an unjust situation rather than a fully formed person. As Jess Bergman recently observed in The New Republic, “without a fuller picture of their lives,” the Town Square workers can “feel more like cardboard cutouts than fully realized people”—a set of walking issues, appearing smaller than the hardships they’ve endured.

Nowhere is this flatness more jarring than in the description of Travis, a young man who has spent time in prison. He is in conversation with Milo, who needs little encouragement to talk at length; when Travis raises his eyebrows, Milo continues “as if Travis had put another quarter in the slot.” Waldman adds: “(as an ex-con, Travis had a lot of experience with pay phones).” It’s a strange break in the narrator’s perspective: the third-person narrator in this novel is mostly staying close to the characters in the scene, telling us their thoughts, but this comment doesn’t sound like it comes from Travis or Milo. What might be a clumsy attempt to connect moments in Travis’s daily life to his experience of incarceration lands instead as a joke at the character’s expense.

The fascinating thing about humans is that nine people with the same job in the same town might do and want all kinds of inexplicable, extravagant, unique things. But there’s a failure here to imagine their aspirations beyond the most obvious variations on the American dream. Big Will just wants a suburban home with “a swing set and a trampoline in the backyard”; Diego dreams of “a spot of land that was his, somewhere where he could drink a beer and look at the sky.”

The pared-down prose can read as simplified rather than plain. Generic references to pop culture provide a shorthand throughout: handsome Big Will is “like a teen idol turned awards show emcee” and, later on the same page, “like the guy in the teen movie who drives the fancy red sports car and wears mirrored glasses and gets all the girls,” while the also-handsome Little Will has “a Ken-doll face.” Comparisons are often made to figures in entertainment: “Big Will’s voice was smooth and sonorous, like a professional DJ’s”; “His expression turned somber, like that of a television news reporter interviewing a hurricane victim”; “He looked like he was playing a homeless person on TV.” The emotional palette is similarly limited. I lost count of how many times these characters “grinned” at each other.

Some of the novel’s tone-deaf moments might be a product of Waldman’s relatively recent venture into the world she is writing about. In an interview with New York magazine, she spoke of her worry that she would not fit in at the big-box store where she worked for a short time as research for the novel. She points out that having a degree from Brown University might have raised questions in the hiring process. She notes that while many of her coworkers had to bike or walk to work (as Diego does in the novel), she had the relative luxury of arriving in her own car. She made “flubs” like poking fun at the store—a place others were proud to work. She reports ultimately winning them over by bringing in banana bread. But the novel is written from the distance and with the awkwardness of an outsider who is conscious of her own advantages and appears wary of speaking out of turn.

This may explain why there’s little conflict in Help Wanted beyond the easy dislike of Meredith and some of the sinister execs who drop in from HQ. There are few tense relationships among the characters, and no one acts unreasonably or has an inexcusable flaw. In fact, Help Wanted often appears to strain to present the rank and file in a good light, as if its mission to draw attention to their working conditions depended on the reader’s seeing what good people they are.

I found myself thinking back to Waldman’s comment that “writing about the romantic and psychological problems of middle-class people” no longer seemed to her “a valid way to spend a career.” To some extent one’s opinion of Help Wanted may boil down to your sense of what fiction is for. Did the election of Trump, and a series of disturbing developments in American and global politics more broadly, render the closely observed novel “comically insignificant,” like the box of books from Penguin Random House that the workers unload from the truck? And if so, is the only type of defensible novel one that resembles a documentary—a log of social conditions and their most visible effects? Or is there an intrinsic value in the careful observation of other people and in the work of imagining their humanity? I am inclined to think that there is and that the people of Town Square Store #1512 might have benefited from the kind of unflinching exploration Waldman devoted to the lives of Nathaniel P. and his friends.

This Issue

April 18, 2024

The Corruption Playbook

Ufologists, Unite!