For me Iran’s sentencing this week of Iranian-American scholar Kian Tajbakhsh to at least twelve years in prison—the harshest sentence so far passed down by the revolutionary court—is particularly fraught. In 2007, he and I were fellow prisoners in Tehran’s Evin Prison. He was held in the men’s section and I in the women’s section of Ward 209, reserved for political prisoners held by Iran’s Intelligence Ministry. We had been arrested within a day of each other, and we shared, in separate interrogation rooms, the same interrogators. He began to send me books; thanks to him I was able to escape the confines of my prison cell by reading the novels of Dostoevsky and Graham Greene.

Now, on October 20, Kian has been convicted, on the kind of fantastical charges beloved of Iran’s revolutionary courts—everything from plotting a “velvet revolution” in Iran to espionage and undermining the credibility of the Islamic Republic. He was even charged with endangering the security of the state by belonging to a public email list, Gulf2000 (which posts news and commentary on the Middle East), run by Columbia University professor Gary Sick, who is falsely identified in the indictment as a CIA operative.

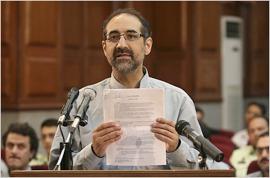

Kian was one of over one hundred Iranians placed in the dock in a mass show trial in Tehran following the demonstrations that brought a million protesters into the streets following June’s contested and almost certainly rigged presidential election.

The accusations we are hearing against the accused today are remarkably similar to those against both Kian and me back in 2007: plotting with the US or unnamed “foreigners” to bring about a “velvet revolution” in Iran—I as the director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, DC, (I was in Iran visiting my mother when I was arrested) and he as a Tehran-based consultant to the Soros Foundation on public health projects. The Intelligence Ministry, I discovered, is obsessed with the activities of George Soros. As my interrogators often reminded me, Soros is a Jew and responsible, they firmly believed, for the velvet revolutions that overthrew regimes in Georgia, Ukraine, Tajikistan and other republics of the former Soviet empire. Soros and the American government, they insisted, were plotting a similar “velvet revolution” for Iran using me and Kian as their witting or unwitting instruments.

I was released in August 2007 after nearly four months in solitary confinement, and Kian was released the following month. I returned to my work at the Wilson Center. Kian, however, chose to remain in the Iran he loves. During the last two years, he has been careful to keep a low profile, devoting himself to his scholarly research, writing and books. He played no part in the post-election protests that led to a brutal crackdown and the arrest of many protesters and leaders of the opposition. Yet on July 9, intelligence agents showed up at Kian’s house, as they had done two years earlier, and arrested him once again, in front of his wife and his two-year-old daughter. He remained in solitary confinement, with almost no contact with his family, until he appeared at the mass trial that got underway in August.

The trial has been a travesty of justice. The initial indictment was directed against everyone at once. There were only three sessions. Some of the accused were paraded before television cameras to make coerced confessions. (Kian made a statement too; he said that the US and Europe desired to bring about change in Iran, but that he had no knowledge of a plot). Kian did not even get to choose his own lawyer and had to make do with a government-appointed one, who said he will appeal.

The trial is further evidence that some of the most hard-line elements in the Intelligence Ministry and the Revolutionary Guards are now setting domestic policy. They have used the trial to attempt, yet again, to persuade an ever-skeptical Iranian public that the Islamic Republic is indeed in grave danger of a “soft overthrow” plotted by England and America, to settle scores with their political adversaries, and to rid themselves, once and for all, of the reformers and moderates in their midst.

The irony is that Kian was within two weeks of leaving for the US to take up a long-standing invitation to teach at Columbia University. He was in no hurry to leave. In his usual, trusting way, he thought the Intelligence Ministry people had stopped harassing him. He little realized that once they have you in their gun sights, these men are never done with you.

Haleh Esfandiari is Director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center, and author of the book My Prison, My Home, just published last month.