By late May, more than ten million copies of E.L. James’s Fifty Shades trilogy, an erotic romance series about the sexual exploits of a domineering billionaire and an inexperienced coed, had been sold in the United States, all within six weeks of the books’ publication here. This apparently unprecedented achievement occurred without the benefit of a publicity campaign, formal reviews, or Oprah’s blessing, owing to a reputation established, as one industry analyst put it, “totally through word of mouth.”

It’s not news that “word of mouth” has become a business model in the book industry. But E.L. James, a forty-nine-year-old former television executive from West London whose real name is Erika Leonard, has exceeded the sales feats of previous reader-discovered authors by such a staggering magnitude that she is in a category of her own. Last year’s breakout success, Amanda Hocking, sold merely a million copies of her self-published young-adult novels over the course of eleven months before signing a four-book deal with St. Martin’s Press.

The crucial difference may have less to do with talent, content, or luck than with a peculiarity of Leonard’s early readership: her work originated as fan fiction, a genre that operates outside the bounds of literary commerce, in online networks of enthusiasts of popular books and movies, brought together by a desire to write and read stories inspired by those works. Leonard’s excursion in the genre provided her with a captive audience of thousands of positively disposed readers, creating a market for her books before they ever carried price tags. But fan fiction is inherently collaborative and by convention resolutely anti-commercial, attributes which make its role in the evolution of her work both highly unusual and ethically fraught.

Beginning in 2009, Leonard posted, under a different title, a version of the Fifty Shades trilogy on a well-trafficked fan-fiction forum devoted to the Twilight series, the vampire-themed romance blockbusters by Stephenie Meyer. Leonard’s “TwiFic” shed Meyer’s supernatural story line and transposed the largely chaste love story of her protagonists, Edward and Bella, into a sexually explicit register. Like many fan-fiction writers, Leonard uploaded her work in serial installments, a method that enables readers to weigh in as the story progresses and allows writers to incorporate feedback as they go. Writers also read one another’s fan fictions and can infer, from the number and tenor of reader responses, what kinds of stories are popular. Leonard’s story reportedly received more than 37,000 reviews, and was read by untold thousands more who did not post reviews.

Early in 2011, after amending the work and expunging all traces of its connection to Twilight, she contracted with a small Australian press to publish it as the Fifty Shades trilogy, in ebook and print-on-demand paperback formats. By March of this year, when Vintage acquired the rights to the trilogy for more than a million dollars, all three books were at or near the top of The New York Times’ combined print and ebook bestseller list.

The vast majority of Fifty Shades’s readers are presumed to be women, as are the vast majority of fan-fiction producers and consumers, and anecdotal evidence suggests that, at least initially, there was much overlap between these groups. At Goodreads.com, a book-recommendation site with more than nine million members, readers began reviewing Fifty Shades of Grey, the first book in the trilogy, in the spring of 2011, many noting that they had first encountered the story in its fan-fiction incarnation. “I loved this story as a fanfic and the characters have stolen my heart all over again!” wrote a reader named Ashley, who, along with more than 55,000 other Goodreads members, gave Fifty Shades of Grey the site’s highest rating, five stars.

Critics, by contrast, have found much to abhor about the work. Many have lamented Leonard’s “stilted,” “cliché-ridden” prose (a typical line: “my very small inner goddess sways in a gentle victorious samba”) and decried as retrograde the sexual mores of her (now renamed) protagonists: Anastasia (Ana) Steele, a willing but inexplicably chaste college senior at Washington State University, and Christian Grey, a buff but troubled Seattle mogul who seeks to enlist her as his sexual slave. Christian is partial to BDSM—an umbrella term encompassing the erotic practices of bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, sadism and masochism—and his penthouse includes a “playroom” kitted out with chains, shackles, whips, and other kinky toys. But before Ana can experience its exquisite tortures, she must sign a contract, devised by Christian’s lawyer, consenting to become his submissive (or “sub”), ceding control over her body, diet, hygiene, sleep, and wardrobe, and stipulating her tolerance for various sexual acts and accessories (manacles, hot wax, genital clamps, etc.).

Advertisement

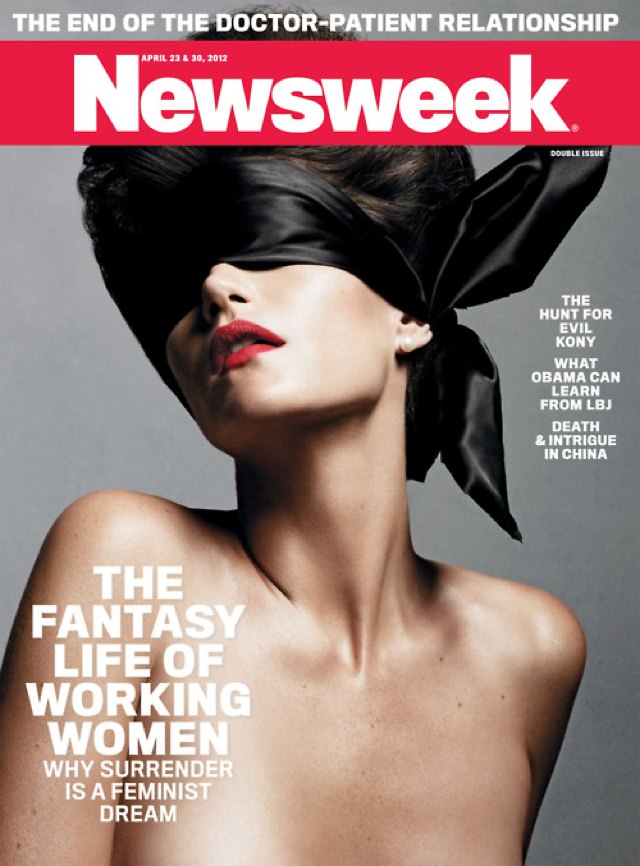

Together, the Fifty Shades books run to more than fifteen hundred pages, many if not most of them sexually explicit. (One of Leonard’s few obvious talents as a writer is maintaining variety in the frequent couplings.) What Ana, who narrates the series, refers to as Christian’s “predilection” lends to the strenuous antics a transgressive frisson. Yet critics have noted that the erotic content breaks no new ground, citing equally explicit, better-written fare, in particular The Story of O, Anne Declos’s indubitably literary portrayal of female sexual slavery, published in 1954. In a cover story for Newsweek, Katie Roiphe concluded that what’s “most alarming about the Fifty Shades of Grey phenomena, what gives it its true edge of desperation, and end-of-the-world ambiance, is that millions of otherwise intelligent women are willing to tolerate prose on this level.”

It’s hard not to hear the unease in such appraisals, the condescension envenomed by a dawning awareness of irrelevance. What sway does a critic have compared with 55,000 members of Goodreads.com or, for that matter, the entire Twilight fandom? It’s tempting to argue that the Fifty Shades trilogy marks the apotheosis of a new industry paradigm, in which power has shifted from high-status cultural arbiters—agents, publishers, and professional reviewers—to anonymous readers and fans. Yet the story the books tell suggests a more ambiguous take on this development. A subplot concerns Ana’s professional aspirations: an avid reader of nineteenth-century romance novels, she hopes to become a book editor and lands a job as an editorial assistant at a Seattle publishing house. We’re meant to understand this achievement as evidence of both intellectual promise and self-reliance. But then Christian buys the publishing house and has her boss, a bumbling sexual predator, fired, effectively becoming her superior and her livelihood.

Is Leonard telling us that there’s no difference between a BDSM contract and a literary one? That all human relationships, romantic and professional, are characterized by gross disparities of power? That one party always has the upper hand—or is trying to take it? Ana attempts to stand her ground. She declines to sign Christian’s contract, and refuses his request that she stop working after their—inevitable—marriage. (Despite the risqué trappings, the books hew to the conventions of the nineteenth-century marriage plot.) However, soon after the wedding, he appears at her office to insist that she use his last name professionally:

“So what can I do for you, Christian?”

“I’m just looking over my assets.”

“Your assets? All of them?”

“All of them. Some of them need rebranding.”…

“Please don’t tell me you have interrupted your day… to come over here and fight with me about my name.” I am not a freaking asset….

“I want everyone to know you’re mine.”

“Look, we’re talking about my name,” Ana responds. “I want to keep my name here because I want to put some distance between you and me…. Everyone thinks I got the job because of you.” Yet by the end of the trilogy, the name of the publishing house has been changed to Grey Publishing, Ana Steele has become Ana Grey, editor-in-chief, and the company has a book on the Times’ bestseller list.

Ana’s professional ascent has an implicit analogy in Erika Leonard’s own trajectory from fan-fiction writer to bestselling author, functioning, for her readers at least, as a kind of allegory avant la lettre. Just as Ana labors to establish a public identity independent of her powerful husband’s, Leonard must dissociate her work from Stephenie Meyer’s in order to claim the prerogatives of authorship. Suggestively, Ana’s efforts are only partly effective, and, though she rises to the top of her field, a whiff of impropriety hangs over her success (“Everyone thinks I got the job because of you”).

Fan fiction, too, exists in a state of dependency, borrowing not only a source work’s fans, who provide a ready-made community of readers, but its characters (and frequently its settings and basic plot) in order to tell the story in a new way. Many writers preface their work with a disclaimer stating that they do not own the copyright to the characters in their stories, and, presumably for this reason, an implicit rule of fan fiction is that writers do not try to profit from it. The genre dates to the late 1960s, when Star Trek fans circulated ‘zines featuring stories inspired by the show’s characters. Fan fiction took early to the Internet, and FanFiction.net, which was founded in 1998, remains the genre’s most popular forum, with more than two million users, who post and read stories derived from books, movies, cartoons, even video games.

Advertisement

The range of titles in the books section is impressively broad: To Kill a Mockingbird is about as popular as Bridge to Terabithia, and The Scarlet Pimpernel, with 220 fan fictions currently posted, outperforms Bridget Jones’ Diary, which has 211. Even Animal Farm has 91. Still, fantasy books predominate, and the Twilight fandom is the second largest, after Harry Potter, with nearly 200,000 fan fictions.

One theory about the genre is that it serves as a corrective to the source work, filling in plot gaps, amplifying subtexts, and expressing beliefs about what should have happened as opposed to what did. On FanFiction.net you can find thousands of TwiFics classified as “Alternate Universe,” or AU, to signify that their plots diverge significantly from Meyer’s. Here her vampire hero, Edward, is variously reconceived as a surgeon, a high-school principal, and a cat, and his teenage human love interest, Bella, as a wedding planner, a divorcee, a US Army sergeant, and an assistant pastry chef. There are children and car accidents, creepy government experiments, divorces, disappearances, and, despite a longstanding ban on explicit content, abundant sexual suggestiveness, if not actual sex. (According to a recent analysis of a billion web searches, FanFiction.net is “the world’s most popular ‘erotic’ site for women.” ) Stories are typically presented without literary pretension or much skill, motivated by an unembarrassed passion that comes from knowing that your audience consists of other people in the grip of the same obsession. Reader reviews tend to be models of positive feedback: “Wow another awesome chapter. We got to see a protective Edward and we finally get to see what Rosalie is up to.”

Leonard initially posted her AU TwiFic, Master of the Universe, on FanFiction.net, under the alias Snowqueens Icedragon, but it was eventually taken down, presumably because it violated the rule on explicit content. She moved the story to her personal website, and in the summer of 2010 she appeared with six other prominent TwiFic writers on a panel at Comic Con, the comic-book convention in San Diego. By 2011, after she transformed Master of the Universe into the Fifty Shades trilogy and published it with The Writer’s Coffee Shop, in Australia, Leonard had an organized fan following. She also had detractors. Some argued that sanitizing a fan fiction for publication, an act known as “filing off the serial numbers,” constituted a betrayal of the genre’s noncommercial ethos and an invitation to legal trouble. Writers had published TwiFics before, typically as ebooks, but none had readerships anywhere near the size of Leonard’s, and some accused her of exploiting the Twilight fandom—“the very fandom that gave her popularity,” as another TwiFic writer put it—for her own gain.

Legally, fan fiction is on uncertain ground. Fan-fiction writers and legal scholars have argued persuasively that the genre meets the legal criteria for fair use, because it is both noncommercial (it poses no economic threat to the copyrighted work) and “transformative” (it adds novel insights or meanings to the source work). But some professional authors, among them Nora Roberts and Anne Rice, have threatened to sue fan fiction writers for copyright infringement, and relevant case law is somewhat contradictory, particularly with respect to fictional characters. In a 1954 case, Warner Brothers, which owned the film and radio rights to The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett’s novel featuring the detective Sam Spade, argued that radio sequels starring Sam Spade violated its copyright. A federal appeals court rejected Warner Brothers’ claim, ruling that unless a character “really constitutes the story being told” rather than serves merely as an instrument for its telling, the character is not protected by copyright.

In 2001, a federal appeals court determined that The Wind Done Gone, a novel by Alice Randall which retold the story of Gone with the Wind from the perspective of a slave’s daughter, a character Randall invented, was a transformative use of the original work and could be published. However, in 2009, a US district court judge banned the publication by a Swedish author of a novel featuring a seventy-six-year-old version of Holden Caulfield, the indelible teenage narrator of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. Lawyers for the Swedish writer, who used the pen name J.D. California, contended that the novel was a critical parody and thus a transformative use of Salinger’s book. But the judge found overwhelming similarities between Salinger’s protagonist and California’s, agreeing with Salinger’s lawyers that the novel was derivative. (The ruling was vacated on appeal but in a settlement reached last year, California agreed not to publish or distribute his book in the US until The Catcher in the Rye enters the public domain in 2026.)

Whether a TwiFic whose only apparent links to Stephenie Meyer’s books are a vampire hero named Edward and a teenage heroine named Bella constitutes an infringement of copyright is debatable. More unclear is whether Meyer’s Edward can still be said to be Meyer’s Edward once he becomes a billionaire or a junkie under a different name in a fan fiction by someone else. Rebecca Tushnet, an expert on copyright law at Georgetown University who has written extensively about fan fiction, has argued that the genre deserves legal protection because

it is only different in degree from a host of activities that are legal: putting on a Barbie and Ken or Star Wars play in one’s front yard; giving an X-Files theme party where not all of the costumes and decorations are officially licensed; and discussing the possible sex lives of TV characters with friends over lunch. Fan fiction often requires a more creative investment than these other activities. Even though it may expose fans to ridicule, it should not expose them to legal liability.

Tushnet was writing in 1997, and in none of her examples do the fans stand to gain financially from their actions. With Fifty Shades, however, fan fiction has taken a provocative step—one that could conceivably have legal repercussions. In March, Anne Jamison, an English professor at the University of Utah who studies fan fiction, told a reporter for NPR.org, “The question now seems to me to be a new one: whether the explicit, conscious use of another writer’s fan base, via creation of characters known and experienced as ‘versions’ of the writer’s characters, for commercial purposes, constitutes any kind of damage or infringement.”

For the moment, Stephenie Meyer seems unlikely to pursue Leonard in court. In May, she told MTV News that she hadn’t read the Fifty Shades books—“that’s really not my genre, my thing,” she said—but indicated that their existence didn’t trouble her. “Good on her, she’s doing well, that’s great,” she said of Leonard. Nevertheless, in certain parts of the Twilight fandom, Leonard’s renown is clouded by a perception of success unearned. On March 13th, Jane Litte, who runs DearAuthor.com, a blog about romance novels, compared Master of the Universe with the Fifty Shades trilogy using Turnitin, a plagiarism-detection program. She found that the texts were 89 percent identical and posted sample passages, chosen at random, in which little more than the characters’ names had been changed—from Edward to Christian, and Bella to Ana. “With the success of Alternate Universe fan fiction and the successful leveraging of that fandom into seven figure economic rewards, the influx of fan fiction into professional publishing is likely to begin at greater levels than previous,” Litte wrote. “I think its important, if we go down this route, that provenance is stated…. It’s an indicator to readers that they may have encountered this before and it gives the fandom that propelled the author to success a nod.”

The post generated nearly three hundred comments. Few commenters were troubled by Leonard’s debt to Meyer; “Hell, one can argue that the historical romance subgenre started out as fanfic of Pride and Prejudice,” one observed. But many felt she had mistreated the Twilight fandom, from whose feedback and support she benefited. “89% for an essay against another would get you kicked out of class in college, but with a fan fic you retitled the reward is a publishing contract,” one wrote. “E.L James has used and taken advantage of Twilight fandom, yes she’s got her fans and supporters but overall she’s left a huge wankfest on her road to publication,” another said. As Anne Jamison, the English professor, elaborated, fan fiction “operates under a certain kind of implied contract—this is not a legal issue, but unwritten, voluntary contracts do regulate people’s behavior. A lot of this unwritten agreement involves give and take, donation of labor (reviewing, reccing, writing, reading) with the understanding that it is a non-profit enterprise.”

Whether it’s ever okay to break that implicit contract, and under what circumstances, was a matter that the commenters did not resolve. Leonard hasn’t shared her views on this issue, but the Fifty Shades trilogy offers some clues. The example of Ana and Christian suggests a fatalistic vision of relationships, as risky entanglements not amenable to contracts or rules and subject to constant negotiations over power. The potential rewards are great, but relationships exact a price. For Ana, the price of a relationship with Christian is an identity and a career that are not quite her own. For Leonard, the price of a relationship with the Twilight fandom is a blockbuster that in the view of some at least belongs to more than her alone.