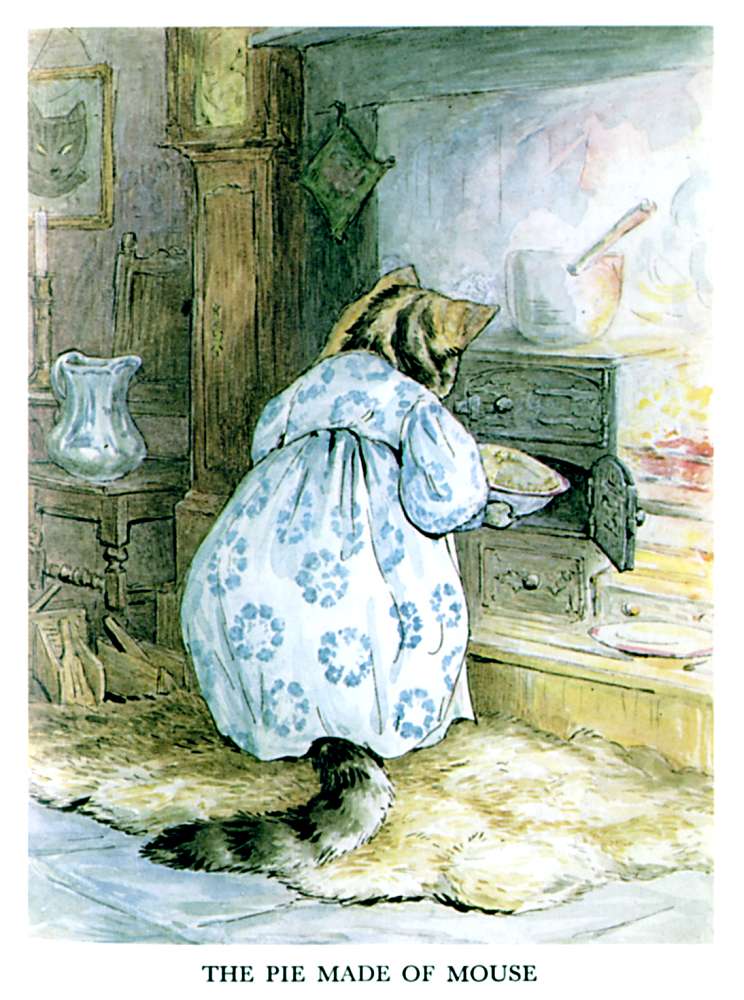

No Christmas story is more charming than Beatrix Potter’s The Tailor of Gloucester, set in the Regency, “in the time of swords and periwigs and full-skirted coats with flowered lappets.” The author said that it was her favorite of all her tales for children. With an important commission due on Christmas day—the mayor is getting married, and needs his resplendent coat “of cherry-colored corded silk embroidered with pansies and roses”—the tailor falls ill. He is hungry, poor, old, and desperate. But he has always been kind to the mice who infest his house, much to the disgust of his servant Simpkin, a cat—and it is the mice who come to his aid in his illness, finishing his commission on Christmas Eve with their nimble sewing, singing cheerfully in their communal act of seasonal charity.

Echoes of other tales, like The Elves and the Shoemaker, and some Golden Age lore, underscore Potter’s commitment to an ideal of creaturely charity that, while couched in some Christian terms, is not dependent on anything so banal as the Church of England; in one remarkable passage, we learn that in the hours of darkness from midnight to dawn on Christmas Eve, all the animals can speak in human language. The Tailor of Gloucester is a deeply satisfying story. But as always with Potter, it owes its “charm”—that inadequate term for what in her best work she so miraculously accomplished—to her willingness also to engage with darkness, to her frank acceptance of envy, and rage, and the carnivorous facts of life. Simpkin, the disloyal servant, is repentant and forgiven at the end—but we know that he will not stop hunting the mice that the tailor will always try to protect. He is a cat; that is what he does.

Accepting the hunting instinct is what gives The Tale of Peter Rabbit its true edge—that, and the unfairness of the mother punishing the adventurous rabbit who just wanted, after all, to eat. Going into gardens to eat lettuce and carrots is what rabbits do; chasing after them with rakes, and hoping to put them “in a pie,” is what McGregors do. As I found when my son was young, it is simply not possible to read the end of the story—when Peter is put to bed and dosed with chamomile tea while his “good” sisters get “milk and blackberries for supper”—without laughing aloud at Potter’s slyly simpering tone. Potter, and we, know that it is Peter who is the “true” rabbit, in all his “badness,” and that of course he will go into the garden again, because that is what bunnies do.

Potter’s deft use, and skewering, of the pious conventions of the moralizing texts of nineteenth-century children’s literature continue to confuse the casual reader, who might be misled into thinking her work merely cute. Extremely realistically drawn animals, many of them dressed in vests, hats, and shawls, of course remind us of what some children do to their pets, and the resulting spectacle may seem either adorable or appalling. Since Potter kept all sorts of animals as pets from a very young age, we can surmise she knew all about rabbits who wriggled out of jackets like Peter, or kittens who scratched when one tried to button them up, like Tom Kitten. An execrable film from 2006, Miss Potter, with Renée Zellweger in the title role, saw only the cute side of things. But as simple-minded as that particular version of Beatrix Potter’s life was, it was from an examination of Potter’s biography that insightful critics such as Humphrey Carpenter, in his essays “Beatrix Potter: The Ironist in Arcadia” (1985) and “Excessively Impertinent Bunnies: The Subversive Element in Beatrix Potter” (1989), first drew surprising conclusions about the nature of Potter’s work, observing among other things that she was deeply engaged with the political and social questions of her day. In 2003, M. Daphne Kutzer’s book Beatrix Potter: Writing In Code did more detailed spade work on similar themes, noting the many occasions in which Potter’s animal characters defy authority or slip through the nets of “civilization.”

At a children’s birthday party—my son was three, and thronged by a host of other toddlers and their parents—I inadvertently caused a ruckus when I launched a game of “pin the tail on the Fierce Bad Rabbit,” reading aloud that Potter story in which a selfish bunny is menaced by a “man with a gun” who shoots off his tail and whiskers. It tuned out that many of my fellow parents had not yet decided to “allow” their children to know that guns exist—although it was clear that they already did. I found myself wondering what cruel streak in me had responded so energetically to Potter’s playful violence (modulated as it was by the rabbit in this case not actually dying but only being, as it were, castrated, like the pesky Squirrel Nutkin who loses his tail in another story) and why it made me laugh instead of worry.

Advertisement

The Tale of Two Bad Mice captures perfectly not only what Carpenter would call Potter’s “subversive” side with respect to bourgeois society, but more primitively, her reworking of what we must surmise are the frustrations of her youth. Famously “kept in” and away from all society by materially comfortable yet socially anxious parents; unofficially engaged (her parents disapproved) at the late age of thirty-nine, to her publisher, who shortly thereafter died; married at last at forty-seven, to a farmer in the lakes district, where she had bought a house virtually in secret from her parents; Potter for her entire life struggled with an extreme version of that Victorian piety, “a daughter’s a daughter for all of her life.” She even kept her own diary in code; it was not deciphered until the 1950s. Perhaps the saddest thing about the secrets contained therein is that they are merely the secrets of privacy: decorous daily doings, descriptions of her animals and the weather, very few complaints, and sober speculations about politics, gardening, and the natural sciences.

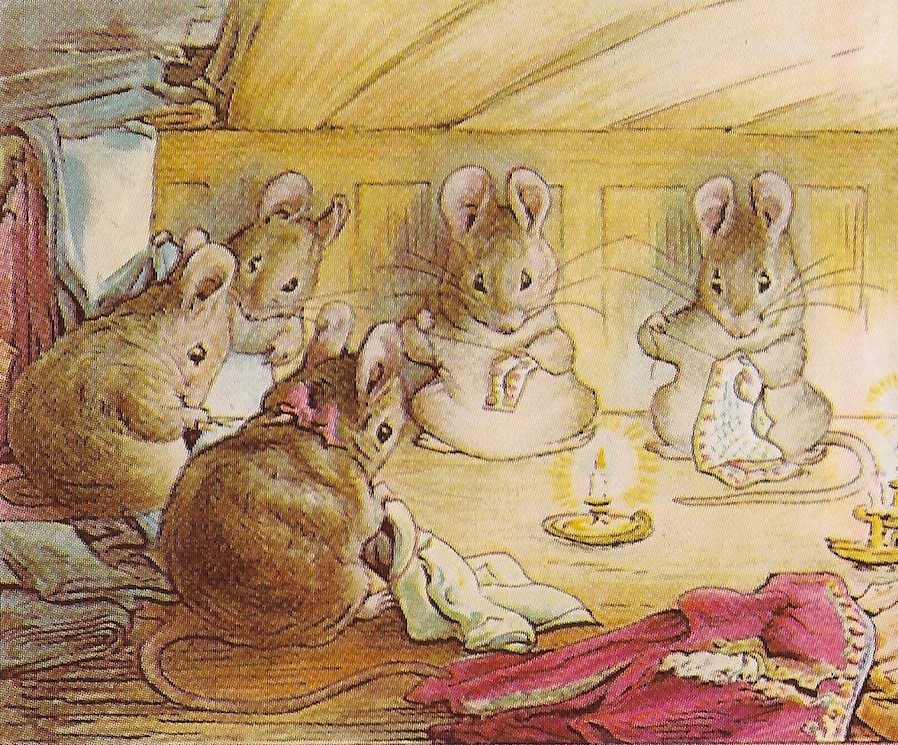

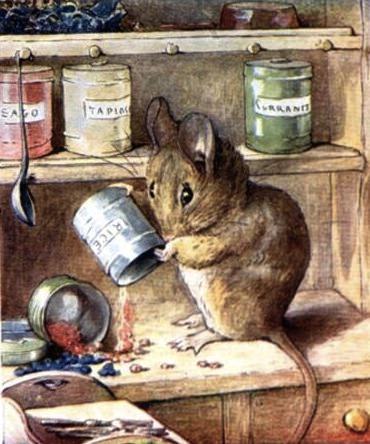

For a creative genius to live for most of her life with intrusive, implacable authority—which all custom and religious teaching insist upon—would have broken someone of lesser spirit or cunning. But it was in Potter’s nature to generate laughter in the face of oppression, and to imagine a liberating “badness” in acts of resistance by bunnies, kittens, squirrels, and mice to the worried demands of their elders. In Two Bad Mice, Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca are enchanted by the dollhouse that arrives in the nursery. When the dolls are away on a ride in a carriage, the mice break in to enjoy the splendors of fine living, set to their own scale. But when they settle down to eat the ham, the fish, and the other treats on tiny doll plates, they discover they are made of plaster. The fireplace does not have a fire; it is colored paper. The canisters in the kitchen contain not, as labeled, Sago and Rice, but tiny beads. “Then there was no end to the rage and disappointment of Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca.” The mice thoroughly vandalize the dollhouse, smashing the plates, throwing clothes out of the window and tearing up the bolsters before stealing some of the usable items for their own home behind the wainscot. Nothing, it seems to me, could more clearly indicate a picture of the betrayal offered by a particular house, where the food is plaster and the warmth is paper.

That the mice become parents soon thereafter, and find the doll’s linens and cradle very useful, and that they repent, to some extent, of their childish mischief (by sweeping the house and offering a “crooked sixpence” at Christmas to pay for damages), demonstrates how Potter can soften a story without diminishing the power of the savage comedy at its center.

I have scarcely touched upon the drawings, which are without parallel in children’s literature (although Sendak’s come close in evocative power) and which are as integral to the storytelling as Potter’s flexible, intimate prose. As with many classics, if Potter’s tales have become invisibly “charming,” it is time to return to them and see them anew. Mothers and fathers are discovering something of this useful discomfort every day they read the tales aloud—but as with many of the enchantments of childhood, they and their children are in danger of forgetting what they see and read. So I urge you to read, to reread, just for starters, The Tale of Two Bad Mice and The Tale of the Pie and the Patty-Pan (almost indescribably bizarre and hilarious) and, for a holiday treat, The Tailor of Gloucester.