My parents took me to see Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood when I was six years old. More accurately, they took me to sleep through it, saving no doubt on a babysitter, but I didn’t sleep. For months afterward, I would lie down at bedtime and vainly try not to think of the terrifying white-haired Forest Spirit in her ghostly hut, whispering prophecies at Kurosawa’s Macbeth, in guttural Japanese, from her rickety spinning-wheel of fate.

Japanese ghosts have returned this summer to haunt my dreams, summoned by a striking Hokusai exhibition in Boston, and by other stray events that stirred up spectral associations with the Japanese master’s mesmerizing art. Not least was the arrival in western Massachusetts of a producer from the Criterion Collection, to film an interview with me about the writer and connoisseur of Japan Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), four of whose Japanese ghost stories are the source for Kwaidan (1964), Masaki Kobayashi’s creepily stylized horror film. Of Greek and Irish ancestry, the exoticist Hearn worked in New Orleans and Martinique before settling in Japan in 1890, where he immediately began collecting and adapting ghost stories—a genre in which Japanese folklore and literature are particularly rich—for collections like Kwaidan (1904), published the year he died, a title that Hearn translated as “weird tales.”

Back in New Orleans, Hearn had tried his hand at Asian ghost stories in his wildly overwritten volume—all red lacquer and gilding—Some Chinese Ghosts (1887). In Japan, aspiring to be the Brothers Grimm of Japanese folklore, Hearn wrote instead in a rigorously plain style (“I am converted by my own mistakes,” he remarked), letting the narrative incidents and the vivid images carry the tale forward.

Kobayashi selected four stark stories from Hearn that invited visual and narrative completion. In one story, a samurai, taunted by an image of a stranger’s face in a teacup, drinks the tea, but Hearn declines to say what happened afterward. “I prefer to let the reader attempt to decide for himself the probable consequence of swallowing a Soul.” Kobayashi takes up Hearn’s imaginative challenge.

In another tale, a man abandons his wife in their destitute village for a good job and rich wife in the capital city, only to repent and return to his first wife, who greets him with joy. He wakes up after “the reconciliation” (Hearn’s title for the tale) only to find, wrapped in its grave sheet, “a corpse so wasted that little remained save the bones, and the long black tangled hair.” For Kobayashi, Hearn’s closing image of “the black hair” (the filmmaker’s own title for this segment) morphs from an erotic fetish into an avenging ghost hounding the faithless husband, amplified by Toru Takemitsu’s eerie, hammering score, across the ruined landscape of the village.

I myself find it hard to believe that Kobayashi, in “The Black Hair,” wasn’t thinking of one of Hokusai’s most famous images, The Mansion of Plates (circa 1831-1832), of a ghostly woman snaking up from a well trailing her long, long black hair. I thought of that black hair when, one recent afternoon, I wandered through the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’s exhibition of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), the Edo-period painter and woodblock printer whose images are known across the world.

Objects in the show are drawn entirely from the MFA’s own astonishing holdings, and some acknowledgment must be accorded to the inspired collector who assembled so many of these treasures. William Sturgis Bigelow, from a prominent Boston family, was trained as a doctor by Pasteur in Paris, but had little relish for medicine. Inspired by Boston-based Orientalists like Edward Morse and Ernest Fenollosa, he traveled to Japan, where he was drawn to falconry and the tenets of esoteric Buddhism. He also collected art on an unimaginable scale, and with a ruthlessly keen eye; he seems to have favored the odd, the astonishing, the bizarre, both in theme and execution.

The show itself is built around the theme of Hokusai’s ingenuity. I was expecting to see small things sharply observed and beautifully, ingeniously executed—arresting views of Mount Fuji from Hokusai’s great series (begun when he was seventy), including Under the Wave Off Kanagawa (circa 1831-1833, known as The Great Wave); lifelike birds and flowers; whimsical manga, a genre Hokusai pretty much invented—and I wasn’t disappointed. But I also found a different Hokusai in Boston—weirder in imagination, grander in scale, more audacious in technique.

Hokusai is widely admired as some kind of realist, and it’s true that no detail seems to escape his notice. One thinks, in this regard, of Hokusai’s youthful apprenticeship to a polisher of mirrors in the Shogun’s employ. While Hokusai chose instead the riskier profession of artist, his “lifelong fascination with reflections and optical effects of many kinds may well be related,” as MFA curator Sarah E. Thompson points out in the helpful exhibition catalog, “to his early experience with mirrors.”

Advertisement

The woman admiring herself in the mirror in an early hanging scroll seems to have her mouth slightly open, as though she’s about to speak. But if you look closely—and you always have to look closely at Hokusai’s work—you’ll see that she’s holding a tiny fruit (the hoozuki, or ground cherry, a symbol of summer) in her mouth, and perhaps making a sound with her tongue on its hollow skin, adding auditory detail to visual. “Hokusai’s beauty may be whistling softly to herself as she admires her red lipstick,” Thompson writes, “with a green shimmer on the lower lip where it is applied most thickly, and teeth neatly blackened for maximum contrast with her white-powdered face.”

But Hokusai was also an inspired painter of ghosts and other phantasms. My favorite is The Mansion of Plates, the image I think Kobayashi was thinking of in Kwaidan. Hokusai’s print is based on a ghost story in which a servant named Okiku accidentally breaks a precious porcelain plate and throws herself in despair down a well, or, in alternative versions, is tossed into the well by her angry master. In Hokusai’s inspired rendition, the ghost of Okiku snakes up out of the well, her long black hair entwined with a serpentine succession of porcelain plates, ghostly counterparts of the broken plate. An exhalation slithers from her lips, as though she—and perhaps the artist himself—is smoking something.

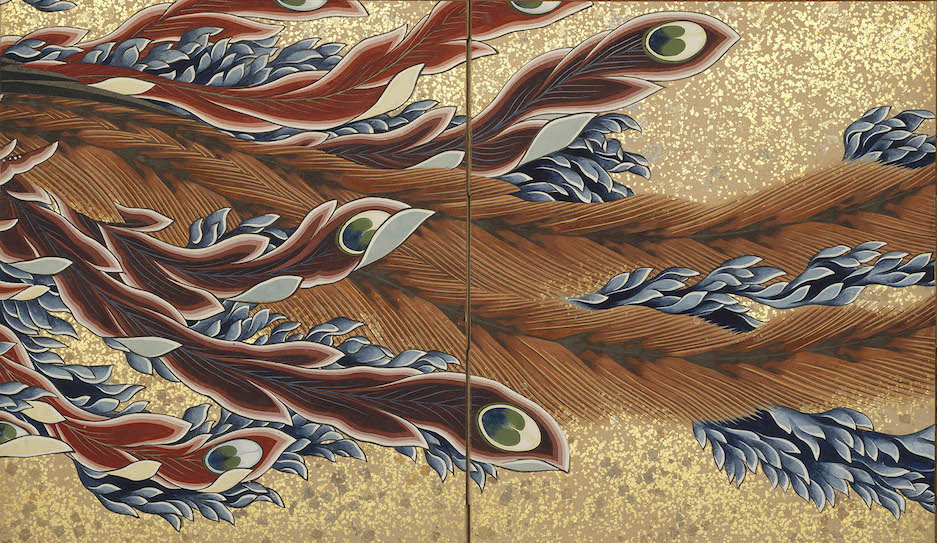

Another fugitive from the world of spirits is Hokusai’s sumptuous and phantasmagorical Phoenix, which takes up eight panels of an eight-foot long (and only fourteen inches tall) folding screen: an explosion of ink, colored pigments, gold leaf, and sprinkled gold. This phoenix, its wings spread out impossibly wide, seems more peacock than any other known bird; with its far-flung tail feathers ending in eyes, it stares back at us like Rilke’s headless Apollo—“for here there is no place that does not see you.”

I found myself thinking of the influence on later artists of both sides of Hokusai’s temperament—the ways he mirrors every detail of the visual world while also evoking, indelibly, the ghostly dream world—as I read a new book by the scholar Christine Guth. Hokusai’s Great Wave: Biography of a Global Icon documents the remarkable diffusion of Hokusai’s best-known image, from Debussy’s La Mer to Mohamed Kanoo’s Great Wave of Dubai (2012), in which the towering Burj Al Arab Hotel replaces Mount Fuji in the distance. Two other exhibitions that I visited this summer, at the Clark Art Institute across the state in Williamstown, further document Hokusai’s wide influence.

“When I look at Hokusai,” Van Gogh (who avidly collected Japanese prints and decorated his studio walls with them) wrote to his brother Theo, “it feels like that wave is a claw and the boat is being seized by that claw.” The Clark’s “Van Gogh and Nature” takes up the Dutch artist’s apprenticeship to the bird-and-flower genre (sunflowers, irises), which Hokusai had restored to a central place in Japanese art a half-century earlier. Van Gogh also adopted from Hokusai, as in the Japanese artist’s beautiful print of The Kintai Bridge in Suô Province (circa 1834), the practice of scoring landscape paintings with diagonal black lines to represent rain.

This technique is given a particularly wrenching treatment in one of Van Gogh’s very last, heartbreaking paintings, of a wheat-field in the rain. The final work in the Clark’s show, the painting depicts a field divided, like the two sides of a river, and spanned by the extended wings of a hovering black crow. Van Gogh’s rain, seemingly incised into the canvas with black paint and a palette knife, is not the gentle summer shower of Hokusai’s print but more like some ominous and inescapable attack from above.

Another sojourner at the Clark this summer, James McNeill Whistler, surrounded himself with Japanese things, as his mother noted when she visited him in 1864; he specifically drew on Hokusai’s bridges for his paintings of London’s Old Battersea Bridge. Irascible and litigious, Whistler passionately collected Asian porcelain, and might have been capable of throwing a clumsy servant down a well. Up the hill from the main building of the Clark, in an exhibition space designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando, resides, for a few precious weeks (until September 27, when it returns to its home at the Museé d’Orsay), Whistler’s Mother, an image almost as familiar as The Great Wave.

Advertisement

There she sits, in ghostly profile, facing a curtain of indigo-dyed Japanese fabric, perhaps a folded kimono, in a geometric array of frames within frames borrowed from the Japanese prints Whistler so admired. She appears, as admirers noted at the time her portrait was painted, in 1871, to inhabit some mysterious inner world—“on the wing,” as the Symbolist writer Huysmans wrote, “towards a distant dreaminess.” Like the serpentine spirit of Okiku, floating up from the well and trailing her black hair, Whistler’s mother seems another summer visitor from the Japanese world of ghosts.

“Hokusai” is on view at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts through August 9. At the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, “Van Gogh and Nature” is on view through September 13 and Whistler’s Mother through September 27.