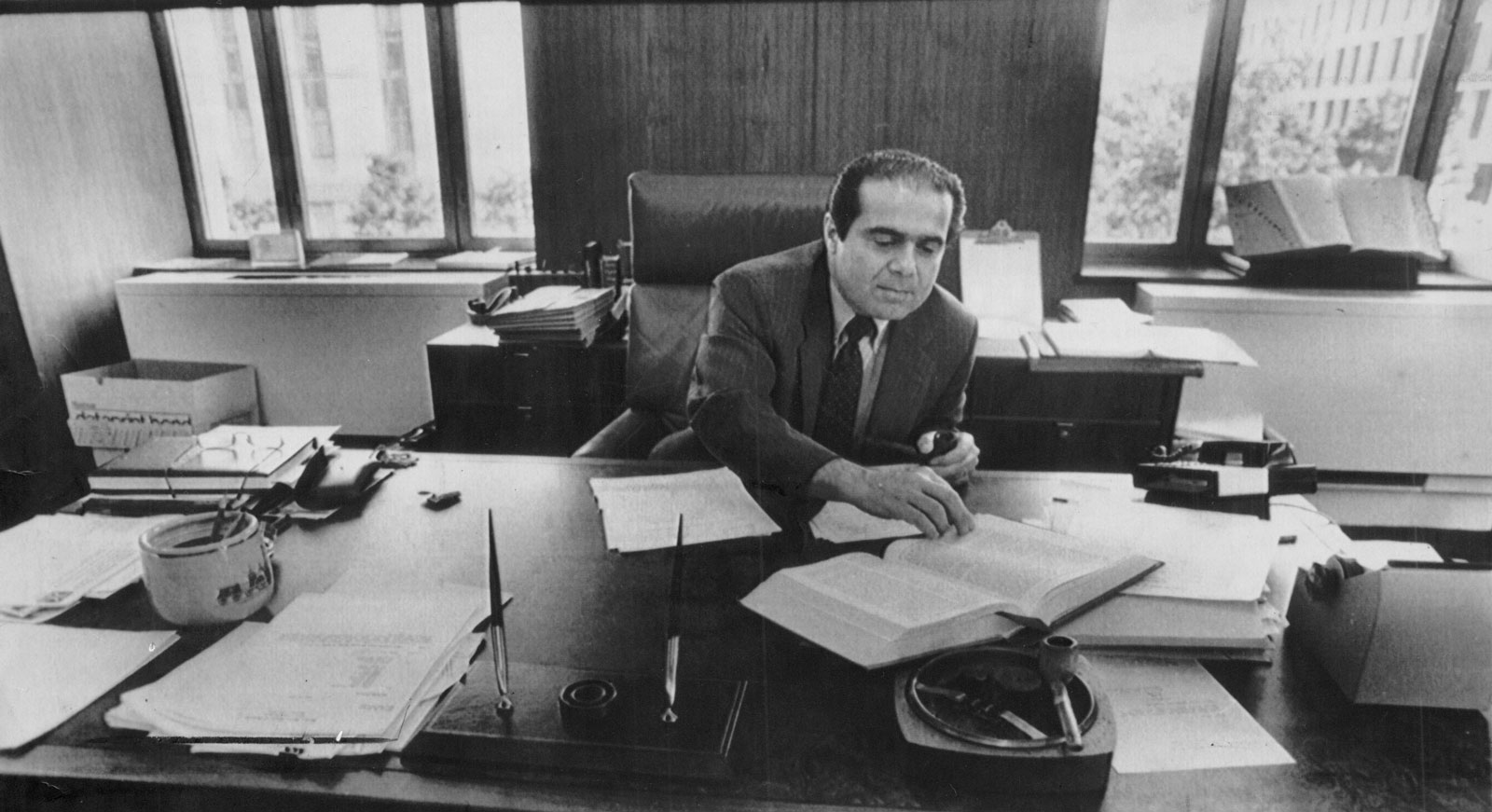

Justice Antonin Scalia used to say, only partly in jest, that he preferred a “dead” to a “living” Constitution: for him, the whole purpose of any constitution worth having was to nail things down so they would last—to “curtail judicial caprice” by preventing judges, himself included, from manipulating the law to advance their own visions of good policy rather than faithfully doing the people’s bidding as expressed in binding rules. Yet Scalia managed to bring our Constitution to life more deeply than have many proponents of a “living” Constitution. His love of vigorous debate consistently pushed his colleagues and legal advocates to improve their interpretive craft, even if he didn’t care for the content of their interpretations; Justice Ginsburg evoked this quality in her touching tribute to Scalia, recalling a duet aria from Derrick Wang’s comic opera Scalia/Ginsburg in which the two justices sing “we are different, we are one.”

Scalia’s ability to bring the Constitution’s text, structure, and history to the very center of the nation’s conversation through elegant and colorful prose should never be confused with the idea that his “originalist” methods actually served the disciplining and constraining functions he attributed to them. Nor should we permit his captivating rhetoric to seduce us into accepting the judgments he claimed those methods required him to reach. I see him, with great respect, as a worthy adversary—but an adversary all the same—of the just and inclusive society that our Constitution and laws should be interpreted to advance rather than impede. Method is insufficient to determine, much less eclipse, outcome when the Court confronts the most significant and difficult questions that the Constitution and federal statutes leave open.

Because ours is a constitutional democracy and not a purely majoritarian system, I have never been convinced that constraining the judiciary is a constitutional end in itself—much less an end to be valued above all others. But even if it were, depicting Scalia’s interpretive methods as more rigorous than others—in the sense that they better restrict judges by rendering their substantive visions of justice and decency less relevant—is an exercise in self-delusion: even in Scalia’s own opinions, text, context, and history were often far less determinate than he liked to assert.

Consider last year’s Supreme Court decision upholding the extension of federal tax subsidies to everyone who needs financial assistance to purchase the insurance required by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), rather than limiting such subsidies to those living in states that had set up their own insurance exchanges. The dueling interpretations of the same language in the ACA, by Chief Justice Roberts for the Court’s majority and by Justice Scalia for the dissent, both took the statute’s text seriously and dissected it meticulously. But only one—that of the majority—read the relevant text with an eye to making the law work as intended. Scalia’s dissent manifested an unseemly eagerness to give Congress a failing grade for its sloppy drafting (it referred to exchanges “established by the state” even when some of the exchanges were established by the federal government for the state). And it displayed an ungenerous willingness to penalize the citizens of the thirty-four states that, at the time of the decision, had accepted the federal government’s offer to set up their exchanges, making them suffer for how their state governments had responded. To blame the sheer perversity of Scalia’s approach to the ACA on a supposed obligation to follow the law’s text to the letter—or on an imagined duty to lift isolated statutory words (like “by the state” rather than “for the state”) out of their context—simply made no sense.

The same inability to pin readers of legal texts down to a single conclusion, however problematic, and to wring from the process all room for disagreement and potentially subjective concern for fairness, haunts Justice Scalia’s ostensibly constraining methods of interpreting the Constitution. In the Supreme Court’s gun-rights decisions, District of Columbia v. Heller and McDonald v. City of Chicago, for example, both Justice Scalia, who wrote for the Heller majority (joined by the Chief Justice and by Justices Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito) and who concurred in McDonald, and Justice Stevens, who wrote dissents in both cases (joined by Justices Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer), sought to interpret the text and fathom the original meaning of the Second Amendment. But they reached opposite conclusions about the reach of the “right to bear arms.” Many historians find Justice Stevens’s account of the origin and history of this right, which noted how narrowly it was understood in 1791, more persuasive than Scalia’s, especially in light of the amendment’s preamble about the necessity of a “well-regulated Militia…to the security of a free State.”

Advertisement

The irony is that, in this pair of ostensible triumphs for Justice Scalia’s methods, the most persuasive argument in favor of the Court’s conclusions came not from the original language or understanding of the eighteenth-century provision in question, but from a much later, nineteenth-century effort to create protections for freed slaves. It was the Court’s reading of the text proposed in 1789 and ratified in 1791 through the prism of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, ratified in 1865 and 1868, respectively—and in light of those amendments’ more contemporary concern with securing the liberties and rights to self-defense of recently freed slaves—that provided the only solid support for the majority’s ultimate conclusion that a limited right to individual self-defense, subject to reasonable state and federal regulation, is now constitutionally protected through the Second Amendment. In other words, Heller and McDonald, far from demonstrating originalism, were actually examples of living constitutionalism, inasmuch as they used the future to shed light on the past rather than the other way around.

Similar questions arise concerning President Obama’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA)—the executive order now before the Court on whose legality most observers assume the justices are divided 4-4. The Constitution offers no direct guidance on how one should evaluate that executive order, which allows undocumented immigrants whose children are American citizens to seek permission to remain in the country and obtain temporary work permits and drivers licenses. The framers were conspicuously silent on whether presidents must exercise their indisputable enforcement discretion on a case-by-case basis—or whether they may instead make rules to bring order to congressionally-enacted immigration policies that cannot possibly be enforced fully without expending vast resources and adopting police-state tactics.

Justice Scalia’s famous insistence that “the rule of law is the law of rules,” and his almost as famous respect for presidential authority, should have led him to join a majority to uphold DAPA. But most knowledgeable observers predicted that he would have voted the other way. Why? Not because his interpretive methods required it, but because his instincts leaned against a law that granted any form of amnesty on a categorical basis to undocumented immigrants. Consider, as evidence, what happened when Arizona, through its infamous “show-me-your-papers” law, adopted the policy of detaining anyone suspected of being in the country unlawfully unless and until the federal executive either verified that the person was here legally or forcibly removed that person. In the 2012 Supreme Court decision invalidating that law, Arizona v. United States, Chief Justice Roberts joined Justice Kennedy in rejecting Justice Scalia’s angry insistence that the states be permitted to step in whenever they are dissatisfied with the executive’s way of exercising of federal deportation power. Scalia’s dissent reasoned that the states’ very decision to enter the Union presupposed a right to override the federal government on issues bearing on their sovereignty – an argument he evidently divined from his understanding of, well, the nature of things. What differentiated Scalia’s view from that of the Court’s majority—a view that Kennedy, in his opinion for the majority, wrote that he found frankly inhumane—wasn’t that the text, history, or structure of the Constitution actually mandated such a conclusion. Rather, Scalia’s reasoning seemed to arise from his palpable frustration with the Obama administration’s substantive approach to immigration.

To say that Justice Scalia’s methods gave him as much wiggle room as his more liberal counterparts to come out either way in particular cases isn’t to accuse him of anything nefarious. It does, however, undermine his claim that, unlike the supposedly more manipulable techniques followed by all of his colleagues other than Justice Thomas, his own methods tied him down to conclusions that he may have disliked but simply could not avoid. This absolute adherence to method over any concern with consequences was something Scalia suggested in criminal justice cases in which he reached results that were more pro-defendant than those of his more conservative colleagues; in those cases, he gave broader effect than many of his colleagues to each criminal defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights to trial by jury and to an opportunity to confront and cross-examine his accusers. Scalia’s indifference to consequences was also something he would announce triumphantly in recalling, whenever challenged to prove that he wasn’t just voting his preferences, how much he hated having to rule in favor of the scruffy flag-burners whose free speech rights he joined a narrow majority in upholding in 1989.

Yet it was the issue of free speech and its intersection with principles of equality that, in Citizens United and related cases, perhaps most called into question the claim of Justice Scalia and his devotees that they were unwavering in their fidelity to “originalist” methods. The deepest question posed by those cases was whether to understand freedom of speech as an essentially absolute, abstract barrier to all federal or state restrictions on the resources and energies devoted to political expression of whatever origin, or instead in a way that takes account of the potential for money and corporate power to distort and corrupt democracy and to undermine the ideals embodied in the core principle of one person/one vote. But that question was not one on which the text or history of the First Amendment or the Fourteenth could provide meaningful guidance, much less supply unambiguous answers, however much the justices in the Citizens United majority insisted otherwise. As I have written at length elsewhere, a great deal can be said both for and against the First Amendment perspective championed by Justice Scalia and promoted with particular vigor by Justice Kennedy, but the question cannot be settled by relying on text and history to the exclusion of political and moral theory.

Advertisement

Nor were Scalia’s declared methods of any help in resolving the question of whether to treat race-specific “affirmative action” as no less constitutionally suspect than the deliberate subordination or segregation of minorities—a question the Court has faced in nearly every case in which minority race has been used by public institutions for purposes of integration and inclusion, from K-12 through the university level. Notwithstanding Justice Scalia’s occasional—and factually inaccurate—claim that the text of the Equal Protection Clause or the Due Process Clause expressly forbids all racial classifications by government, the Constitution in truth says nothing at all about race in either provision. To the contrary, Scalia’s claim that the Fourteenth Amendment as a whole sets its face against all government reliance on an individual’s race or ancestry is belied by the actual history of the amendment and the assumptions both of those who drafted it and of those who voted to ratify it. The amendment was proposed by the very same Congress that created the famous Freedmen’s Bureau expressly to benefit not only the freed slaves but those descended from them. In leading the Court’s opposition to all racial distinctions by government, even when narrowly tailored not as blunt quotas but as one of many attributes to be considered in assessing individuals in a good-faith effort to achieve the advantages of diversity, Scalia ultimately relied on what he identified as a general “American principle” that people should not be classified “on the basis of the color of their skin.” But what then are we to make of Justice Scalia’s idea, which he voiced angrily in dissenting opinions in cases concerning sexual autonomy and gay rights, that reliance on such sweeping principles is but an excuse for judges to impose their own policy preferences undemocratically?

The indeterminacy of Scalia’s methods, as well as the fact that Scalia himself sometimes abandoned their use in cases where they could have cut against the outcome he sensed was right, should particularly remind those responsible for nominating and confirming his successor that brilliant, personally decent, and ethically respectable judges on any side of a complex and controversial issue can quote scripture to their own purposes and, in the rare instances where scripture has nothing to offer, will craft other ways to tip the scales in favor of the results that simply feel right to them. Justice Scalia drew selectively both on his own favored methods and on those of others, often showing a Swiss-cheese-like respect for precedent (following where the logic of precedent led—except when he thought it unwise to do so) to cast real votes on decisions that had real, sometimes enormous, and occasionally tragic human consequences. His successor will likewise have to draw on a broad variety of interpretive tools and will, likewise, in the most significant and controversial cases, ultimately rely—whether expressly or otherwise—on a personal understanding of the values and vision that the Constitution is best understood to embody.

The selection of a justice to serve for life on the nation’s highest court is far too consequential to be treated either as an abstract referendum on legal methodology or as a game to be played for partisan advantage. For literally the first time in American history, the party in control of the Senate is demanding that the president violate his constitutional duty to nominate someone to fill a Supreme Court vacancy. In the process, the Senate is effectively disabling itself from performing its own constitutional duty, its “Advice and Consent” function, thereby undermining the framers’ brilliant design of a government whose separate parts were to check but never prevent one another from performing their assigned missions. The national debate over who should be the next president might in any event include attention to the kind of justice the people want to see fill the currently vacant seat, but that debate will inevitably be far more generalized and lacking in substance if it cannot center around what is revealed by a particular nominee’s background and in that nominee’s responses to probing questions asked in a Senate hearing.

Nothing could more dramatically demonstrate how momentous the choice of a successor to this justice is to the country, and how especially shameful and hypocritical is the Senate’s refusal even to consider anyone nominated by the incumbent president. The pretense behind this unprecedented maneuver is that only the president whom the nation elects this November to succeed President Obama can legitimately reflect the people’s will. Never mind that President Obama was elected in 2008 and reelected in 2012 and still has nearly a year to serve. The claim is that filling the currently vacant seat in ordinary course would unduly politicize the selection process and the Court itself. That is transparently absurd. Whichever president nominates someone to the seat occupied by Justice Scalia, the selection that is made, and the Senate’s vote to confirm or reject that nominee, will reflect a politically legitimate choice about one kind of future rather than another with respect to the powers, responsibilities, and limits of the levels and branches of government and the values government will be permitted, forbidden, or on occasion compelled to preserve. Justice Scalia’s successor will wield enormous influence on the Court’s decisions in years to come on the broadest imaginable range of matters vital to us all: access to court and avoidance of arbitration in civil cases, meaningful access to adequate legal representation in criminal cases, presidential war powers, voting rights, reproductive choice, gay rights and minority inclusion, racial and religious profiling and the separation of church and state, campaign finance and habeas corpus and the future of such extraordinary and deeply debated forms of punishment as solitary confinement, life imprisonment without parole, and the death penalty.

Many of us yearn for the Court to move in a progressive direction and dread a continuation of the rightward drift that Justice Scalia’s three-decade long presence on the Court facilitated. Even if labels like “liberal” and “conservative” are often oversimplifications, it captures more truth than it obscures to say that the Court is currently composed of four liberals (Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan), three conservatives (Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Thomas, and Justice Alito), and one jurist (Justice Kennedy) who leans sometimes in one direction and sometimes the other way. The Court is exquisitely balanced 4-4 on a wider swath of fundamental questions than at any time since the 1930s.

This crucial constitutional moment—this possible turning point in the life of our republic—calls on all of us, across the political spectrum, to drop the pretense that we have nothing in mind but what we deem the theoretically proper judicial methods, come what may, and simultaneously to resist the unfounded claim that only those who applaud right-leaning outcomes while proclaiming strict adherence to text and history can truly claim the mantle of constitutionalists who believe in the rule of law. That mantle instead belongs to those who are most candid about the non-existence of any ironclad “method” that should, or even can, obviate the necessity for human choices about the demands of justice and the meaning of America.

The greatest justices in our history—from John Marshall to Louis D. Brandeis, from Robert H. Jackson to Earl Warren and William O. Douglas and Thurgood Marshall and William J. Brennan, Jr.—have displayed that candor and have thereby helped make the Union stronger, the country better, and our Constitution more enduring and embracing. We should all welcome the opportunity to take part in a national debate over the values and perspectives we want the next justice to bring to the intricate task of interpreting our Constitution and our laws. But if we shut our eyes, ears, and minds to such questions, or reduce them to vague abstractions, as the Senate is now threatening to do, we will leave our nation’s remarkable constitutional system impoverished and our nation’s uncertain destiny imperiled.