Walter Benjamin contrasted the “well-ventilated utopias” of the distinctive German writer and illustrator Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915) with the “overheated fantasies” of the Surrealists. To bring our culture to a higher level, Scheerbart argued in Glass Architecture (1914), his marvelous utopian novel in the form of an aesthetic manifesto, the heavy Wilhelmine buildings of brick and stone needed to be replaced with glass, “which lets in the light of the sun, the moon, and the stars, not merely through a few windows, but through every possible wall, which will be made entirely of glass—of colored glass.” One of his rhyming aphorisms might be translated: “Without a palace of glass/ Life is a pain in the ass.”

Scheerbart lived mainly in Berlin, “in bohemian chaos and near starvation,” according to one biographer. He drank, heavily, with August Strindberg and Edvard Munch, pored over Huysmans’s novels with their Symbolist illustrations by Odilon Redon, and wrote copiously, first art criticism and then fiction, poetry, and plays, with little popular success. Often characterized as a fantasy writer prone to hallucinatory visions of inner and outer space—with early stories set in heavily exoticized “Arab lands”—Scheerbart could also bring an odd, Borgesian precision to novels like his 1910 Perpetual Motion: The Story of an Invention, or to the high-tech schemes of a Chicago-based, glass-obsessed architect in his 1914 novel The Gray Cloth with Ten Percent White: A Ladies’ Novel (both of which are available in English). Disappointment with how his visionary stories were illustrated—by some of the best illustrators of his age, such as Alfred Kubin and Félix Vallotton—inspired Scheerbart to take up drawing himself.

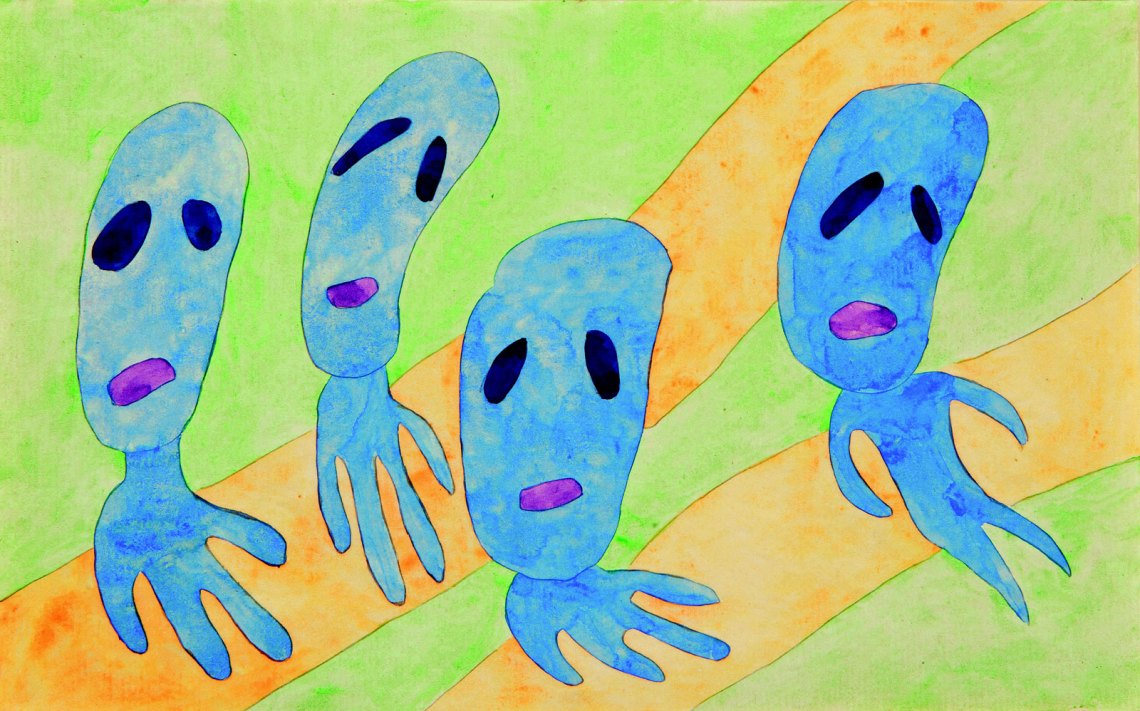

In a recent exhibition and accompanying catalog, the Berlinische Galerie has brought some of Scheerbart’s most indelible images together with the graphic work of two artists he inspired: the modernist architect Bruno Taut (who built a pineapple-shaped glass dome building in Cologne in Scheerbart’s honor) and the little-known outsider artist Paul Goesch (killed by the Nazis in 1940, in their murderous purge of the mentally disabled), whose miniature and colorful architectural visions owe something to Scheerbart.

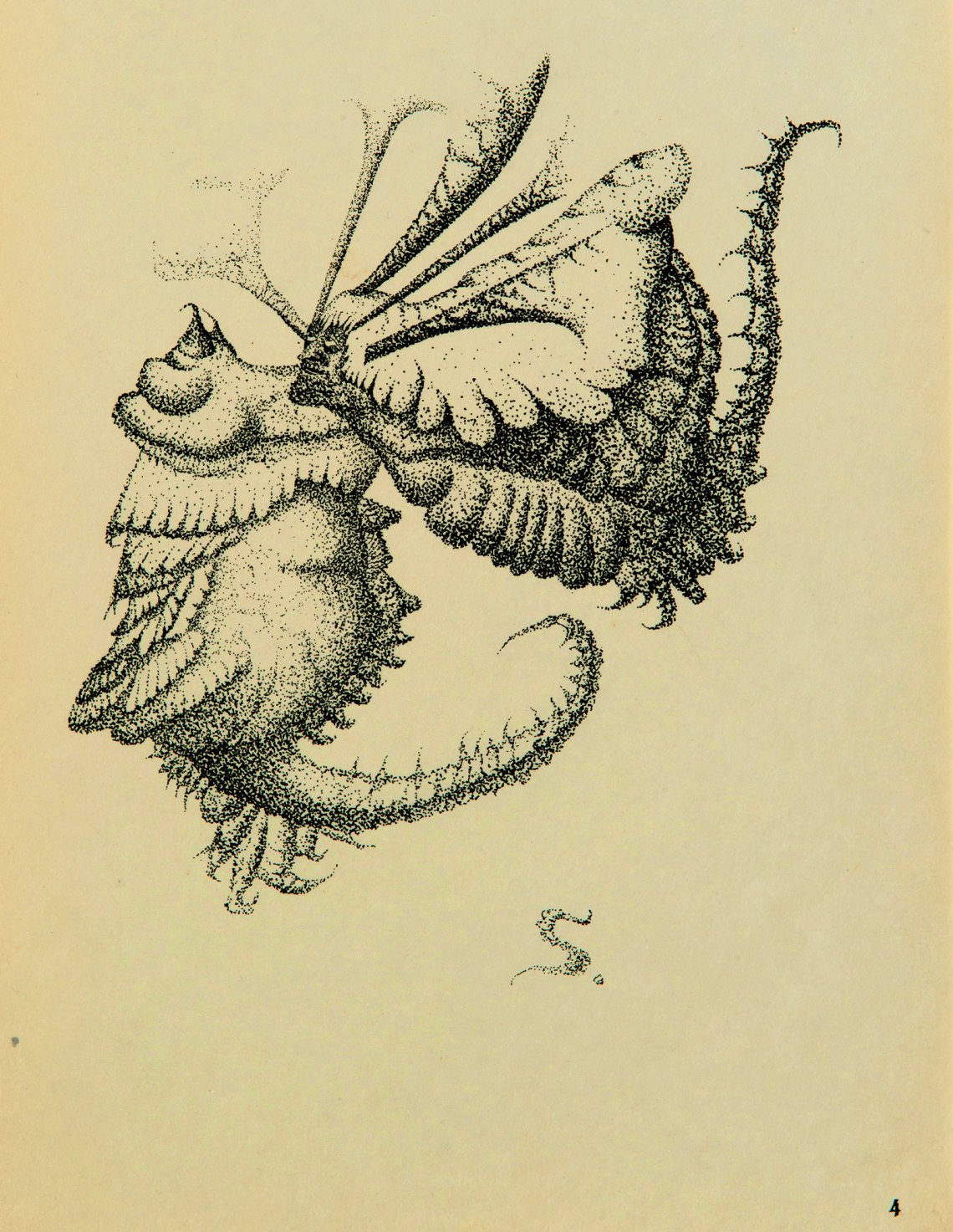

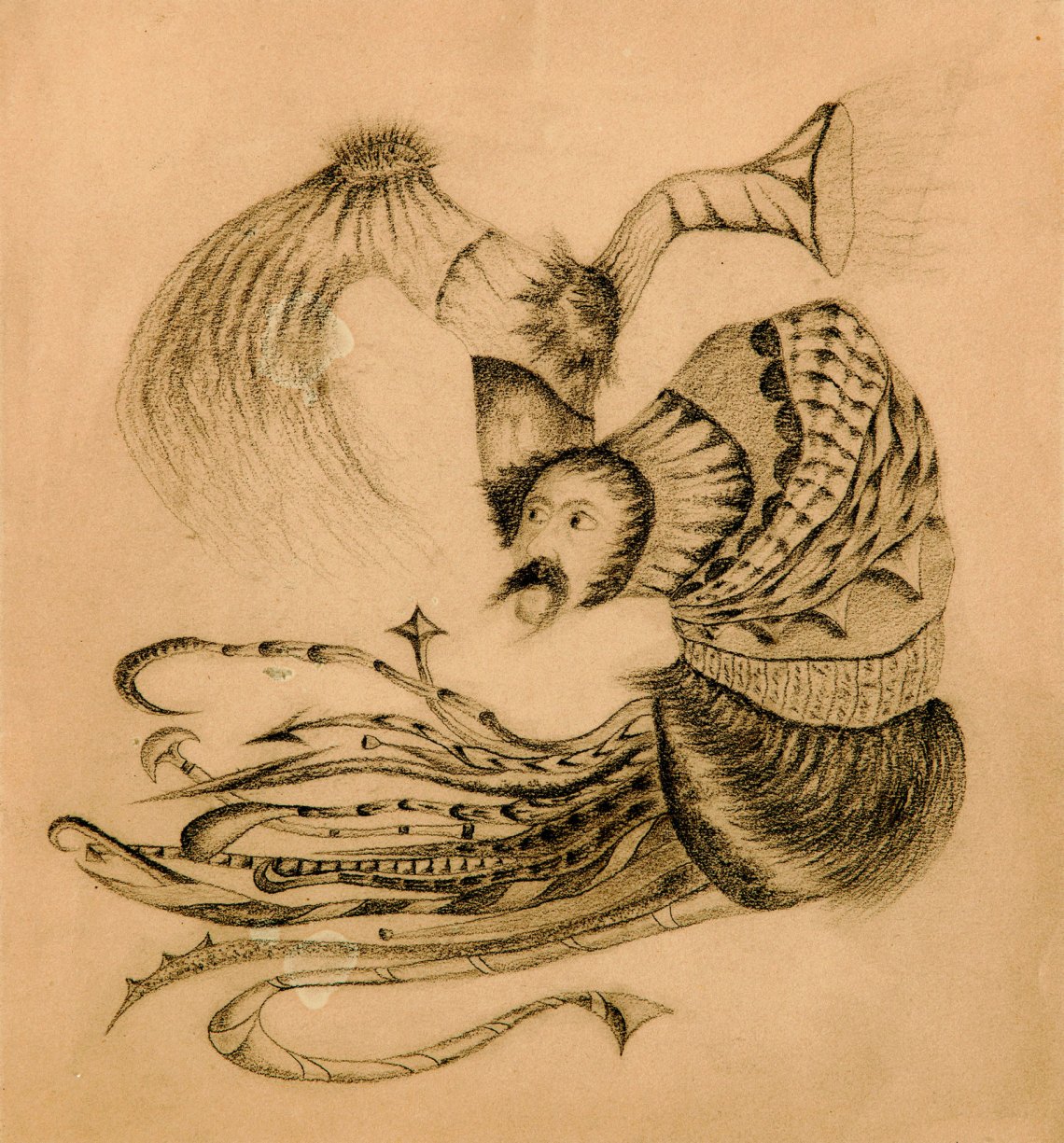

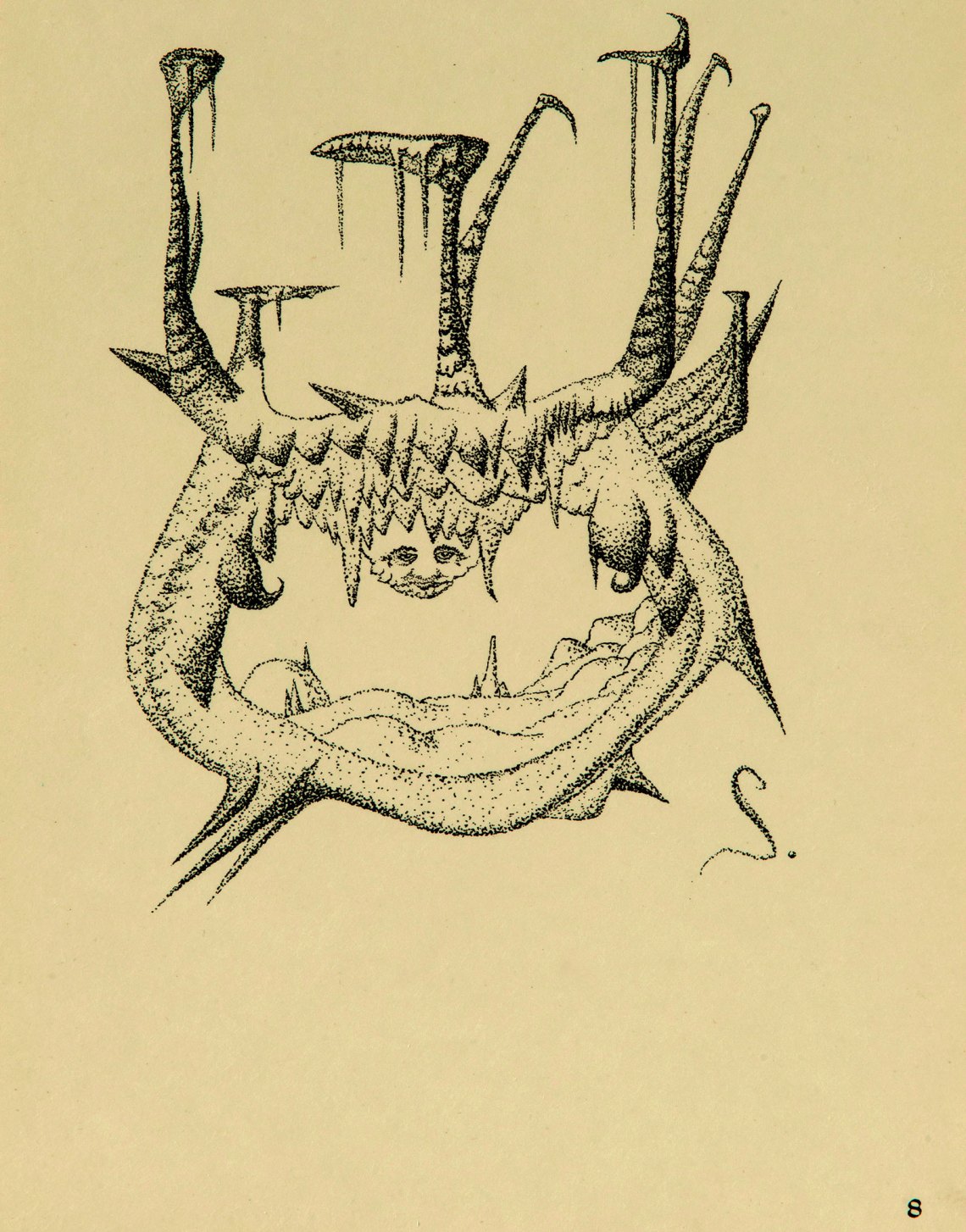

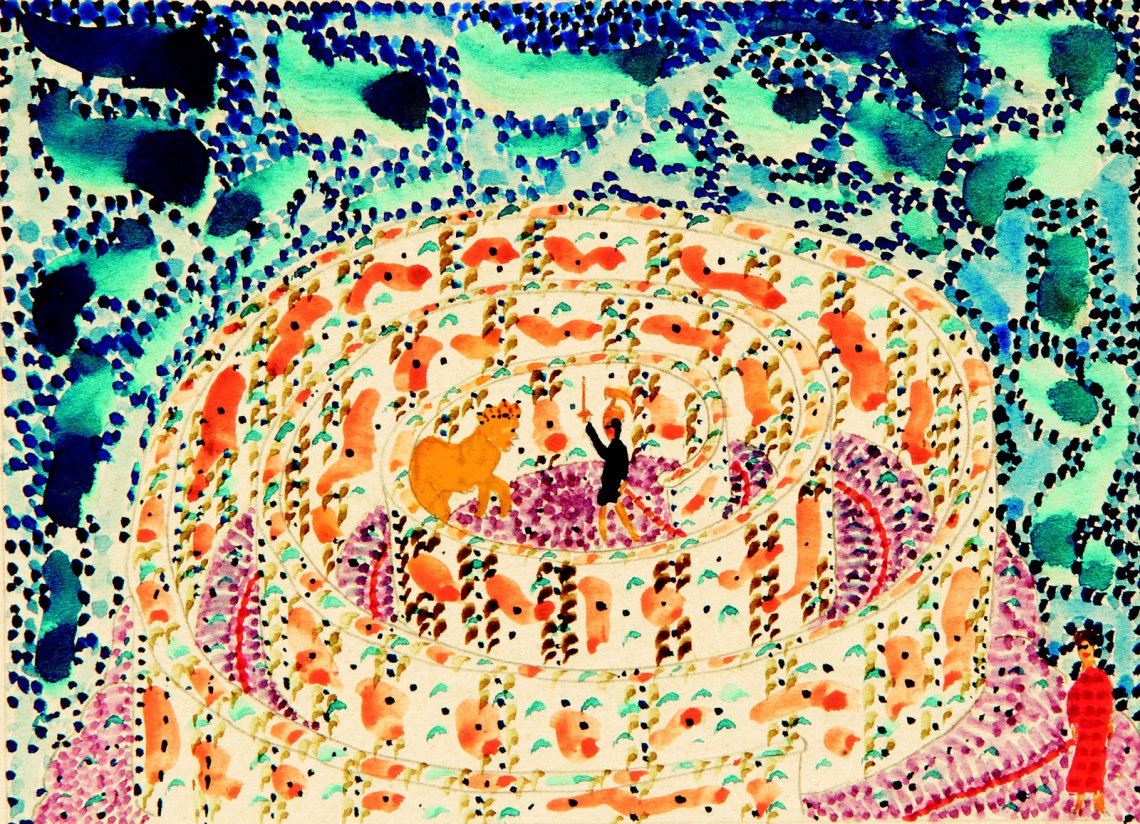

Scheerbart’s drawings, airy nothings composed of dotted ink, are as well-ventilated as his utopian novels. To illustrate his asteroid fantasies, based on early photographs of outer space, Scheerbart perfected a distinctive style of vanishing pointillism. “Beyond Neptune, on the ‘other’ asteroid ring discovered there—,” he confidently informed Kubin, “there are stars that consist solely of masses of air in which the new beings hover about as if in a dream.” Scheerbart’s Jenseits-Galerie (Gallery of the Beyond), a folio of ten masterly lithographs published in Berlin in 1907, purported to depict such “new beings,” always equipped with a human face. One, evidently distant from the Sun, bristles with frozen stalactites.

Another has a volcano sprouting, like inspiration, from its head. Ein Luft-Bonaparte (An Air-Bonaparte) would seem to be another airy nothing encountered out there, though its snail-like body and tentacles might suggest a submarine origin instead. Its S-shape and the absence on the sheet of his customary signature “S” raise the possibility that Scheerbart was modestly depicting himself as a conquering Napoleon of the Beyond.

In his futuristic writings, Scheerbart presciently predicted the rise of China, the formation of the European Union (which he hoped would reduce international conflict), and the nightmare of aerial bombardment, which he thought, mistakenly, would be so terrible that it would put an end to war. (He is rumored to have starved himself to death in protest of World War I.) In “Transportable Cities” (1909), more hopefully, he imagined lightweight urban clusters that could be packed up and moved, by car, from place to place. “At the beginning of culture, man was a nomad, and in the end he will be a nomad once more.” Walter Benjamin saw in Paul Klee’s little sketch of an Angelus Novus the sorrowing Angel of History, facing the horrors of the past, with outstretched wings, and helpless to do anything about them. It is tempting to see Scheerbart’s Ein Zukunftskind (A Child of the Future) as an equally alarming vision of the future. With its lobster claws jutting directly from its temples, this hovering creature looks perfectly capable of surviving us all. Scheerbart’s signature S looks like its larval form, patiently waiting its own turn on our blighted planet Earth.

Advertisement

“Modern Visionaries: Paul Scheerbart, Bruno Taut, Paul Goesch” is published by Scheidegger & Spiess and distributed by the University of Chicago Press.