Daily, I slice bread with my maternal grandmother’s bread knife. Neither beautiful nor valuable—its handle scored white melamine, its wide serrations still sharp—it connects me to my mother’s hands (that used this knife) and to my grandmother’s hands (smaller than my mother’s, arthritic already when I was born); to my grandmother’s kitchen, beloved in my childhood; and to the long-ago morning light that filtered through the sunroom into that kitchen, in a long-sold house, in a far-off city. All this is present when I take it up and tackle a loaf. No other knife will do.

Matisse, unsurprisingly, had similar feelings about the objects of his daily life. They delighted, inspired, or confounded him, in their humble ordinariness and in all that they evoked: a chocolate pot, a green glass vase, a pewter jug, embroidered hanging cloths (haitis) from North Africa, masks and figurines from sub-Saharan Africa, a brazier, a marquetry coffee table, a low-slung chair. Present in photographs of his studios over the years, they appear, too, in countless drawings, paintings, and sculptures; and they can now be seen in “Matisse in the Studio” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, alongside the works that draw upon them, in a dance of recurrences and self-referential variations, spanning, chiefly, Matisse’s mature years.

These mundane items, the organizing principle for this exhilarating show, served as sparks for Matisse’s art. Assembled in the gallery, they also provide an occasion for fresh reflections and analyses by the exhibition’s curators. Essays gathered in the catalogue—by Ellen McBreen, Helen Burnham, Jack Flam, and others—illuminate various threads of Matisse’s oeuvre, including his interest (shared with Picasso, as well as with contemporaries such as Brâncusi and Man Ray) in African masks and sculptures, specifically the simplicity and directness of their forms. This fascination emerges in his paintings—notably, for example, in his painting Seated Figure with Violet Stockings (1914), a nude that, in style and stance, closely resembles a Fang-region reliquary figure that he prized; and in his heartbreaking portrait of his wife Amélie, the last for which she sat for him, although they were married for another twenty-seven years before separating. In this portrait, the mask-like set of Amélie’s features and her hollow black eyes echo the tribal masks he collected. He explored the mask effect also in his sculptures, as in the series of Jeanne Vaderin (a frequent model for Matisse around the time of World War I), her features ever more abstracted, their planes in each iteration fiercer and more simplified.

Pattern and texture were also vital in Matisse’s work, nowhere more so than in his use of patterned textiles in his paintings. He sought to disrupt the traditional balance of figure and ground, so that they might carry equal weight. This exhibition demonstrates this effect, among other places, in his odalisque paintings, undertaken in his Nice studio in the 1920s. McBreen explains that, favoring the theatrical, Matisse constructed fictional “sets” for his models, evoking the “Bed Chambers” of Orientalist iconography, harem beds fashioned from overlapping hanging fabrics: “Dressing the studio with these objects and textiles was an extension of dressing the model. They provided the means to unite her pictorially with the space around her. That, in turn, helped Matisse achieve a different mode of sensuality in his Nice paintings, one that did not rely on the primacy of the female figure.”

In this setting, the lounging women—rather unsettlingly like the precious objects that recur elsewhere throughout his works—are transformed into patterns themselves, their adornments and sensuous lines in conversation with the elaborate textiles around them. In Seated Odalisque (1926) for example, or in Odalisque on a Turkish Chair (1928), we see the odalisque simultaneously as the painting’s focus and as an energetic form among others. Rounded breasts, hips, and thighs blend visually with the arched and undulating lines of textiles and wall-hangings; the sharper lines of arms and feet, particularly in the latter painting, speak instead to the lines of the Turkish chair itself, strikingly pale and structural in the brighter visual palette.

Advertisement

Much has been said, and there is much to say, about Matisse’s vibrant use of color, his increasing simplicity and freedom of shape and line—the miracle of his fruitful artistic reinventions late in life—and, especially in this exhibition, about his repeated returns to and riffs upon beloved motifs, a sort of visual Goldberg Variations. The catalog’s essays and the museum labels also address the ways in which Matisse’s deployment of African and Asian artworks and traditions may appear to contemporary viewers as cultural appropriation, even as the artifacts function as fundamental formal lessons for his work.

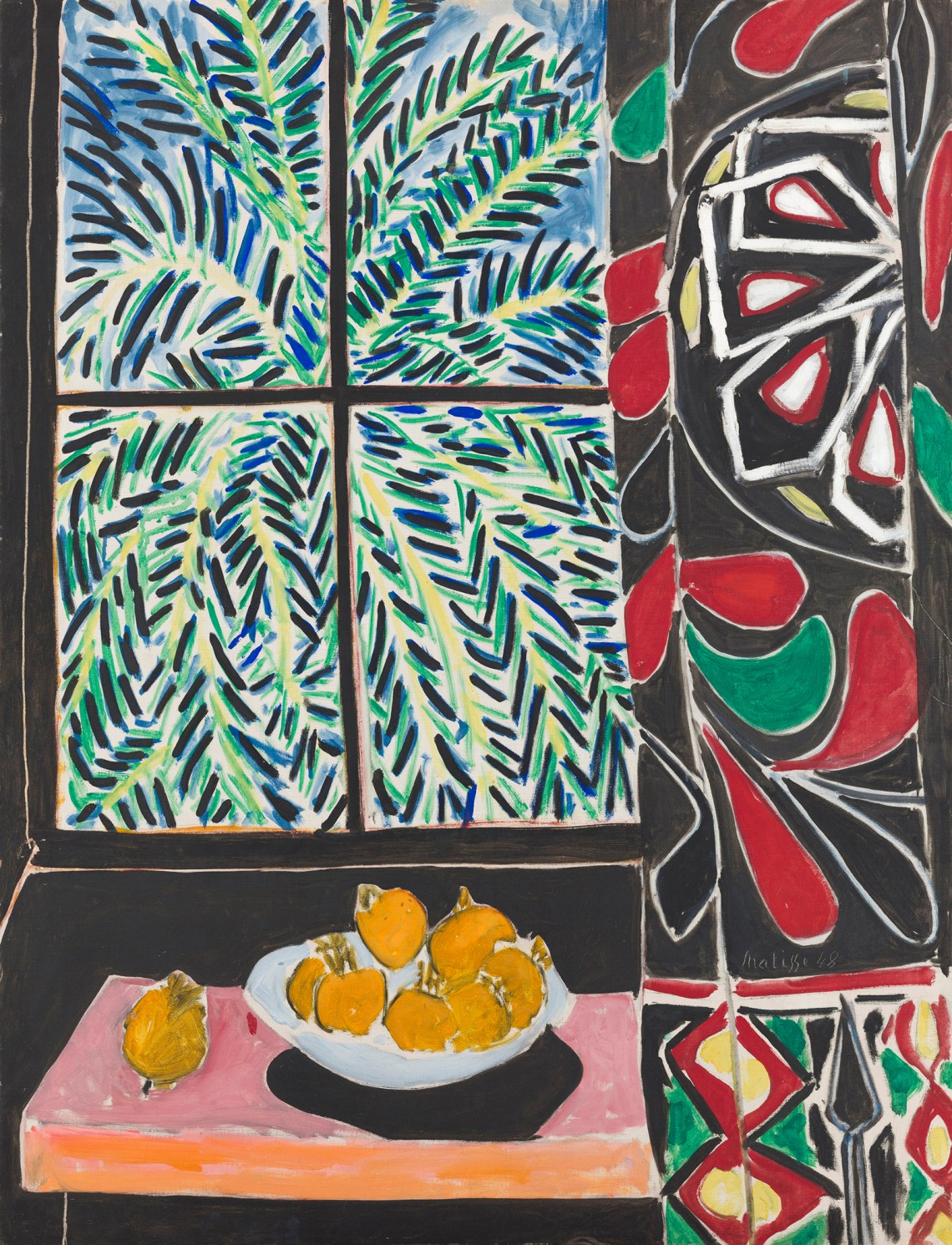

But this glorious exhibition impresses the viewer also with simpler, more atavistic and abiding truths: Matisse’s passion for color, for light, for pattern, for flowers and the female figure; and his conviction—borne out in almost every one of his paintings and sculptures, whether a sublime nude woman’s torso small enough fit in the palm of your hand or an imposing complex oil painting such as Interior with Egyptian Curtain (1948)—that what endures is certainly matter: the flesh, the fruit, the flowers, the folds of fabric. But what counts, above all, is the emotion that we invest in that matter. As Ellen McBreen writes, “the authenticity which most concerned Matisse was that of his own emotional response.”

To anyone other than my sister or myself, the scuffed old bread knife is just that; to only two of us is it magical, eliciting waves of meaning and emotion. In his renditions of beloved objects, Matisse sought to convey to all viewers what they conjured in him; in this sense, his enterprise was the transmission of a joy that surpasses words.

“Matisse in the Studio” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through July 9. The catalog, edited by Ellen McBreen and Helen Burnham, is published by the MFA, Boston.