2017 was the one hundredth anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution and the year in which ISIS was decisively defeated and its caliphate dismantled. While both movements may seem safely behind us, and are separated by a century and almost three thousand kilometers, they are connected by a thread of significance that we would be rash to consider mere history.

Pace Marx, history does not always repeat itself as a farce. Sometimes, perhaps more often than not, it returns as yet another tragedy. Much like the Bolshevik revolution, this initially minuscule extremist movement accomplished the improbable feat of rapidly attracting tens of thousands of followers from all over the world, conquering major cities and vast tracts of land, and creating a new state. ISIS “set a new standard for extremist groups,” wrote Shadi Hamid, an authority on Islamism, “proving it possible to capture and hold large swaths of territory… without the benefit of widespread popular support.” Not quite. Lenin and the Bolsheviks had set that standard long before. Despite the very obvious ideological differences, there are striking similarities in the traits of both movements that seem to account for their unlikely (if impermanent) triumphs.

*

In his memoir of Lenin, Maxim Gorky confessed that in 1917, after Lenin called for a socialist revolution in his “April Theses,” he, Gorky, thought it a hopeless and dangerous endeavor: “Lenin was sacrificing the tiny army of politically advanced workers and the entire revolutionary intelligentsia” by “throwing them, like a handful of salt, into the swamp of the [Russian] village to dissolve there, changing nothing in the spirit, day-to-day existence and the history of the Russian people.”

Gorky was far from alone in his wariness. Attempting to seize power from the Provisional Government before the Constituent Assembly was elected looked like a reckless adventure—and not just to most of the other Russian Social-Democrats, especially the Mensheviks, who at the time dominated the Soviets; a majority of the Bolsheviks were opposed to it, too. Among the doubters was Lev Kamenev, one of Lenin’s oldest and closest associates, the future chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, a Politburo member, and chairman of the Moscow Soviet. Shortly before Lenin’s arrival from Switzerland, as Richard Pipes relates in The Russian Revolution (1990), Kamenev argued at a closed meeting of the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee that while the “bourgeois” Provisional Government was destined to be overthrown eventually, “the important thing is not to take power: it is to hold on to it.”

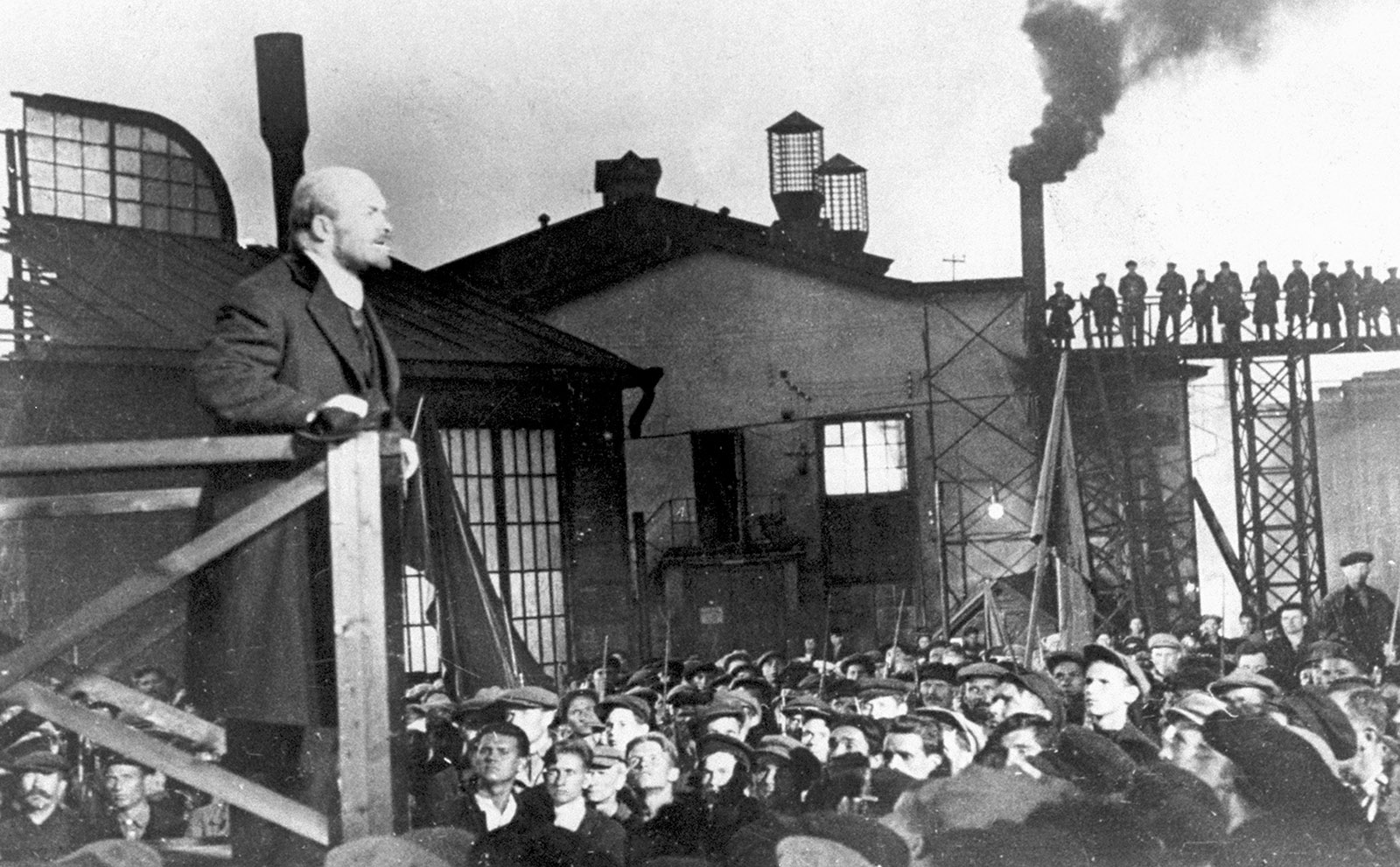

Kamenev had a point. There were 23,000–24,000 Bolsheviks in a country of 150 million people. As for the class that—in accordance with the dictates of Marxist historical materialism—was supposed to accomplish the revolution, industrial workers numbered no more than three million (or 2 percent of the country’s population); and among them, the Bolsheviks had far fewer adherents than did their moderate ex-comrades, the Mensheviks. That, barely five months after the “April Theses,” the Bolsheviks did in fact seize power and hold onto it, saw their numbers swell and their regime extend and solidify its reach over an enormous country, is a story that continues to mystify and fascinate despite having been told many times. It is a story worth dwelling on so it remain fresh in our minds should history decide to produce yet another version of the same tragedy.

Both the Bolsheviks and ISIS capitalized on the strains and brutalization caused by seemingly endless slaughter: for the former, World War I; for the latter, Syria’s viciously sectarian civil war. Daily hardships multiplied, civilizing institutions collapsed, and savagery ensued. In one of his most beautiful poems, “A Decembrist” (“Декабрист”), written in 1917, Osip Mandelstam captured the atmosphere (my own translation, below):

Всё перепуталось. И некому сказать

Что, постепенно холодея,

Всё перепуталось. И сладко повторять

Россия, Лета, Лорелея.[Everything’s in disarray. And no one’s there

To say, as cold sets in, that disarray

Is everywhere. And how sweet it becomes the prayer:

Rossiya, Lethe, Lorelei.]

Like a body drained of life, the country is growing “cold.” Its soul, like those of the Greek dead, is drinking of the Lethe, the river of forgetting, that runs through Hades. Memory is addled, and history can caution no more. Russia is also under the spell of Lorelei, the Rhine mermaid, who, like the sirens of the Odyssey, lured ships to their doom with enchanting songs. As Richard Pipes notes (in his 1994 study, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime), Lenin described the same situation with characteristic flippancy and matter-of-factness: “The power was lying under our feet in the street; all we had to do is pick it up.” Toppling the Provisional Government, he added, was like “lifting a feather.”

Advertisement

Mass terror helped, as well. In both cases, violence was not contingent, but relentless and central to the ideology, targeting groups, or “classes,” rather than individuals. Stigmatizing, demonizing, and dehumanizing the “enemy” was a trait common to both movements. Individual guilt or innocence mattered little so long as victims belonged to a category judged guilty: the “bourgeoisie” or the Shiites, “counterrevolutionary agitators” or Sufis, the kulaks or the Yazidi. Indulging, indeed reveling, in grotesque brutality also advanced the cause. Standing Clausewitz on his head, Lenin treated politics as a war by other means, and the objective was not a mere surrender but “complete destruction.” One of the founders of the Cheka, Iosif Unshlikht, recalled how Lenin “mercilessly made short shrift of philistine Party members who complained of the mercilessness of the Cheka, how he laughed at and mocked the ‘humanness’ of the capitalist world.”

As one of Lenin’s top lieutenants and personal friends, the St. Petersburg Party chief Grigory Zinoviev, put it, “We must carry with us 90 million of the 100 million of Soviet Russia’s inhabitants. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated.” With appropriate substitution of the victimized category, what ISIS commander would not heartily welcome this call to action from a Red Army newspaper: “Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies by the scores of hundreds, let them be thousands, let them drown in their own blood… [L]et there be floods of blood of the bourgeoisie—more blood, as much as possible.” The founder of ISIS, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, “pushed… brutality to unprecedented levels,” which shocked even the al-Qaeda founders Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, who reportedly pleaded with Zarqawi to “restrain himself,” at least in his massacres of Iraqi Shiite civilians.

The Bolsheviks and the jihadists were also alike in their rationalization of violence. Both believed they had been given absolution—by, respectively, History or God. They killed humans to rescue humanity, whether from capitalist “exploitation” or “idolatry.” They felt supremely lucky—nay, chosen and privileged—to be instruments of an ordained deliverance. In a recent book on the Soviet collectivization, Anne Applebaum quotes a Communist activist:

I firmly believed that the ends justified the means. Our great goal was the universal triumph of communism, and for the sake of the goal everything was permissible—to lie, to steal, to destroy hundreds of thousands and even millions of people, all those who hindering our work or could hinder it, everyone who stood in the way.

This belief in predestination animated both groups: the inexorability of the future, and thus of victory, as foretold in the sacred prophesies of Marx or Mohammad. They could not fail. Alive or dead, they won. Napoleon used to say that a battle was won or lost in the minds of the combatants before the first shot was fired. Is there an energy more powerful or a cause more mesmerizing and irresistible, or confidence in the inevitability of victory greater than the one generated by the ecstatic hope of liberating humanity from the miseries of daily life and ushering it into a conflictless Eden? Hence, also, the shared obsession with eschatology: winning meant the end of the known world and the advent of a new one, made to the prophesied specifications. Al-Zarqawi was reported to “inject the apocalyptic message into jihad,” and ISIS made the apocalypse the central element of its ideology, a strategy shaped by “when they thought the Mahdi was going to arrive.” (Hailing mostly from elite Sunni families, al-Qaeda’s founders, bin Laden and al-Zawahiri, were said to “look down” on the eschatological content of Islam, which they considered “something that the masses engage in.”)

Of course, in the Bolshevik eschatology, the sun was not to rise in the West, nor the Mahdi to reveal himself; nor was Issa (Jesus), Islam’s prophet second only to Mohammad, to lead the troops of the faithful into the final battle. Yet theirs, too, was a self-imposed mission to bring about the end of “prehistory” and forge nothing short of a new civilization, conveying humanity, as Engels put it, “from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom.” Marx called the proletariat “the messiah-class”: with History acting instead of God, the proletariat the “universal redeemer,” and the revolution meant “ultimate salvation.” Labelled by the French philosopher Raymond Aron a “Christian heresy” and a “modern form of millenarianism,” Marxism “places the kingdom of God on Earth following the apocalyptic revolution in which the Old World will be swallowed up.”

To be sure, once through death’s door, ISIS fighters and Bolsheviks parted ways: the former believed themselves to be headed to Paradise, while to the militantly atheistic Russian revolutionaries the service to the world proletarian revolution and the gratitude of future generations were their only rewards. Yet the glorification of death for the cause was central to the ideology of both movements. Islamic State fighters are reported to have been not only willing to die, in Shadi Hamid’s words, “in a blaze of religious ecstasy,” but to welcome death. “Being killed… is a victory,” the Islamic State’s spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani declared.

Advertisement

For his part, Lenin confessed to his comrade Karl Radek that he had “sought to reconcile Marx with the Narodnaya Volya”—the People’s Will, a nineteenth-century revolutionary organization whose member Ignaty Grinevitzky, the killer of Alexander II, was likely the world’s first suicide bomber. According to Avrahm Yarmolinsky’s account in Road to Revolution (1957), the animating cause for the group’s key organizer, Alexander Mikhailov, was “his religion… inseparable from his belief in God.” Knowing full well that he was doomed, Mikhailov considered himself “fortunate” to be part of the movement: “A lucky star has shown over my head,” he wrote. “Who does not fear death is almost omnipotent.”

Lenin’s elder, and much beloved, brother, Alexander Ulyanov, was a member of the terrorist section of the People’s Will, and, as Yarmolinsky describes, “a man… who calmly accepted the prospect of self-immolation in the service of the cause.” Sentenced to be hanged for conspiring to kill Alexander III, he told the court that terror was “the only weapon at the disposal of a small minority,” which relied solely on their “spiritual strength and the consciousness that [they were] fighting for justice” and who “will not consider it a sacrifice to lay down their lives for the cause.”

It could be argued that, mutatis mutandis, many extremist chiliastic sects have been in thrall to similarly rigid ideologies and pursued them with a comparable zeal. Still, very few succeeded as spectacularly and as quickly as ISIS or the Bolsheviks. It appears that, in both cases, a vital catalyst of success was the anchoring of their movements in a physical space, translating ideology into state power, and crystallizing doctrines into tangible real estate. Lenin called it “the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat.” The proponents of “political Islam”—for instance, Abul Ala Maududi, an important modern Islamic philosopher and the founder of Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest mass religious organization of South Asia—called it hakimiyya, which Shiraz Maher renders in Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea (2016) as the “securing of political sovereignty for God.” To recall the title of Irving Louis Horowitz’s brilliant essay on Hegel, “Romancing an Organic State,” Lenin and al-Baghdadi both “romanced” a millenarian state.

Romancing is one thing but, again in both cases, consummating the marriage of ideology to state was not merely an operational challenge, as Kamenev pointed out. For both Lenin and al-Baghdadi, declaring the “state of the dictatorship of the proletariat” or the Islamic State and, especially, the caliphate, was a doctrinal leap, a rather significant deviation from the dogmas of both movements. The notion of such a state, writes Graeme Wood in his masterful The Way of Strangers (2016), belongs to “a minority interpretation of Islamic scripture,” and this version of Islam was said to bear only a passing resemblance to the Islam practiced or espoused today by most Muslims. Indeed, the original al-Qaeda jihadists, and certainly Osama bin Laden, had an “aversion to state building” and to declaring a caliphate on its territory. The caliphate was “controversial,” reports Maher, even among many militant Salafis, who made up a majority of ISIS fighters.

Lenin’s doctrinal predicament was more complicated still. To the extent that Engels (it was almost exclusively Engels, and not Marx) dwelled on what would happen after a socialist revolution—and he wrote precious little on the matter—he described the state as “a special agent of suppression of the masses by the ruling class” that would not be needed any longer after the proletariat took power. In a classless society, the state would either be “extirpated” once and for all by the revolution, or “wither away,” or “sink into a slumber.” Socialism, according to Engels, meant the absence of a state.

Hiding in a Finnish forest after an unsuccessful Bolshevik insurrection in July 1917, in what was to become his most important political testament, State and Revolution, Lenin argued that, far from being versions of the same phenomenon, the state’s “extirpation” and its “withering away” were two distinct and sequential processes. First, the proletariat “smashes” the bourgeois state (as Marx wished the Paris Commune had done) and establishes the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Then, and only after such a state is well established, can it begin to “wither away.” Stretching Engels still further, Lenin claimed that “repression,” that most hated attribute of the class-based state, would also be preserved: “a special apparatus, a special machine of repression” would still be necessary.

Another hurdle arose from the core tenets of historical materialism: a socialist revolution was to happen first in mature capitalist countries, not in one where serfdom had been abolished less than sixty years earlier and where the peasants were still an overwhelming majority of the population. As was the case with all the modes of productions that had come before it, ran the Marxist orthodoxy, capitalism was to collapse from the unresolvable contradiction between the economic basis and the political superstructure when it reached its highest stage of maturity. It followed that capitalism must be well established in a country before the conditions would be ripe for a socialist revolution.

Twisting Marxism, as was his wont, to justify immediate political objectives, Lenin argued in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism that the uneven development of capitalism during its final, imperialist stage makes it possible for less-developed countries, as imperialism’s “weakest links,” to shortcut the process. And so, immediately upon his arrival in Russia from exile, he declared in his “April Theses” that, far from entering an open-ended period of capitalist “bourgeois-democratic republic,” Russia’s “bourgeois” stage was already over and it was ripe for a socialist revolution.

Yet for both Lenin and al-Baghdadi there remained one more ideological obstacle, and perhaps the tallest: the obsolescence, indeed anathematization in both ideologies of the key attributes of a state—nationality, national cultures, national sovereignty, national borders. Both leaders circumvented this by emphasizing the purely temporal, instrumental nature of their creations: the sole mission of the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the Islamic State was to serve as the base, the catalyst of, and a magnet for a “world revolution” or a global caliphate. As Trotsky put it, the Bolshevik Party “set itself the task of overthrowing the world.” Once masters of the Russian state, Aron wrote, “Lenin and his comrades began by awaiting the European or world revolution in the same way as the early Christians awaited the Second Coming of Christ. The Islamic State, too, “crav[ed] an all-out civilizational war,” according to Graeme Wood. Like the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the Caliphate “served a dualistic purpose between temporal and cosmic ends,” the latter, writes Maher, being served by “hastening the day of resurrection.”

It was this “cosmic” attribute of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the caliphate that eventually became the weightiest component of their legitimacy in the eyes of the faithful. A “home of a religion of temporal salvation,” in Aron’s words, the sway of the Soviet state ranged from “peasants of Asia” to “atomic scientists” in the West. Jihadists, too, did not regard the “seizure of Mosul as a local victory,” Wood reports. “Instead, first as murmur and soon as a roar, they insisted that ISIS’s ascendance was an event of world-historical import. Indeed, to call it world-historical would diminish it, because the entire cosmos was in play.”

*

The doctrinal daring paid off spectacularly. After a Bolshevik state was in place, the Party’s membership grew from under 24,000 in February 1917 to 250,000 in 1919, and to 730,000 in 1921. Following the establishment of the Islamic State in northern Syria with the capital of Raqqa in 2013, and al-Baghdadi’s declaration of a caliphate a year later, the ranks of the movement swelled from an estimated 1,000–2,500 in 2012 to between 20,000 and 31,500 in 2014.

Much of the upsurge, undoubtedly, was due to the anticipated rewards for loyalty, as well as sanctions for defiance, associated with state power. As the historian Pipes put it, “they joined because membership [in the Party] offered privileges and security in a society in which extreme poverty and insecurity were the rule.”

Yet the early Soviet state and the Islamic State were hardly ordinary states, and the growth of support cannot be explained solely, or even perhaps mainly, by the lures of steady employment and jobbery. There is an abundance of evidence in memoirs, as well as in journalistic accounts (and, in the Russian case, such brilliant fiction as Vasily Grossman’s “In the Town of Berdichev”), that for many converts the realization of a millenarian dream was an appeal of a different and, at least for a time, far more powerful kind. The motives of its acolytes would also ring true for many of the early recruits of the Bolshevik state, as Graeme Wood writes:

ISIS asked its followers to join not because it was fighting US troops—an orthodox bin Ladenist goal—but because it had established the world’s only Islamic state, with no law but God’s and with a purity of purpose that even the Taliban had not envisioned… The breadth of the appeal of the Islamic State was… shocking in its depth… Tens of thousands… had all drunk their inspiration from the same fountains. In addition to the physical caliphate, with its territory and war and economy to run, there was a caliphate of the imagination… They believed the state that awaited them would purify their lives by forbidding vice and promoting virtue. Its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, would unify the world’s Muslims, restore their honor, and allow them to reside in the only truly just society where they would enjoy perfect equality.

*

On March 2, 1919, resplendent in military garb as he addressed in the Kremlin what was to become the founding session of the Third International, Moscow-ruled worldwide communist organization, Lev Trotsky declared that the “mole of history” had not done badly under the Kremlin walls.

A whimsical animal, this mole can also connect passages seemingly far apart. At its height, ISIS is estimated to have had 9,000 citizens from the former Soviet Union, easily the single largest national contingent. Of these fighters, some 4,000 were from Russia itself and 5,000 from the former Soviet republics of Central Asia, the latter mostly Russian-speaking, radicalized and recruited on Russian construction sites. Second only to Arabic by the number of fighters speaking it, the language of the erstwhile Bolshevik state became a language of the caliphate.

Stretching from Mandelstam’s “disarrayed” Russia to disarrayed Syria, the millenarian thread will surely continue its infectious run through teetering or failed states.