When Flying Officer Ulric Cross, a tall, elegant black man with a plummy voice, was introduced in the 1943 Ministry of Information film West Indies Calling, the bomber navigator from Trinidad revealed the degree to which West Indians regarded Britain as the motherland, felt awed, privileged, and protected by her, and were keen to “do their bit” in the fight against Hitler. British viewers were also able to see, many for the first time, people from the imagined far-off colonies, who sounded, but for a slight sing-song Caribbean lilt, just like them. For a brief moment, the boundary between Britain and Empire collapsed.

Viewers were eased into the film by a scene with a jazz band whose musicians might have seemed American but were, in fact, from the Caribbean islands. Indeed, the early West Indian émigrés arriving in Britain were often exoticized in ways similar to those experienced by visiting African-American performers. In 1948, disembarking from the Empire Windrush, the ship that brought to Britain one of the first large-scale groups of West Indian migrants, the Calypsonian Lord Kitchener serenaded the waiting camera crews with a love song spelling out his fellow West Indian passengers’ enthusiasm for the motherland, “London is the Place for Me.” Starting in 1943, the BBC World Service had broadcast “Caribbean Voices,” a program that was to kickstart and nurture Caribbean literature and draw fledgling writers such as V.S. Naipaul, Derek Walcott, and George Lamming from the regions to the metropolis. Those postwar voyagers little knew that they were pioneers blazing a trail for those who would follow their lead and head to Britain over the next two decades.

Some seventy years later, the “Windrush generation” has returned to the center of attention in Britain—not this time in a spirit of optimism and hope but of hurt and anger. Last week, when member of Parliament David Lammy stood in the House of Commons to give an extraordinarily passionate speech, lambasting the Home Office and the government’s actions and inaction as “a day of national shame,” he did so in the service of the Caribbean-born children of Ulric Cross’s generation who came to England in the 1950s and 1960s, and who are now threatened with dispossession, even deportation. Despite their having lived in the UK for decades, working and paying taxes, many of these black Britons lack the paperwork to prove their immigration status—thanks to a very British bureaucratic anomaly. As a result, many have lost jobs, as well as access to benefits and healthcare; some face losing their residency rights.

People from the English-speaking Caribbean prized their British passports, but their status changed when many of the islands became independent of Britain in the 1960s. Never mind that their passports bore the stamp “right of abode”—they had now to apply for naturalization in order to become British citizens. Today, myriad descendants of migrants who arrived as children but whose parents, unbeknownst to their children, did not complete the additional paperwork have now, decades later, been reclassified as illegal immigrants. They are threatened with repatriation to countries which they have little memory of, and may not have returned to for half a century. Apparently acknowledging this attenuated connection, the British government produced a helpful guide for deportees, including linguistic tips: “Try to be Jamaican… Use local accents and dialects (overseas accents can attract unwanted attention).”

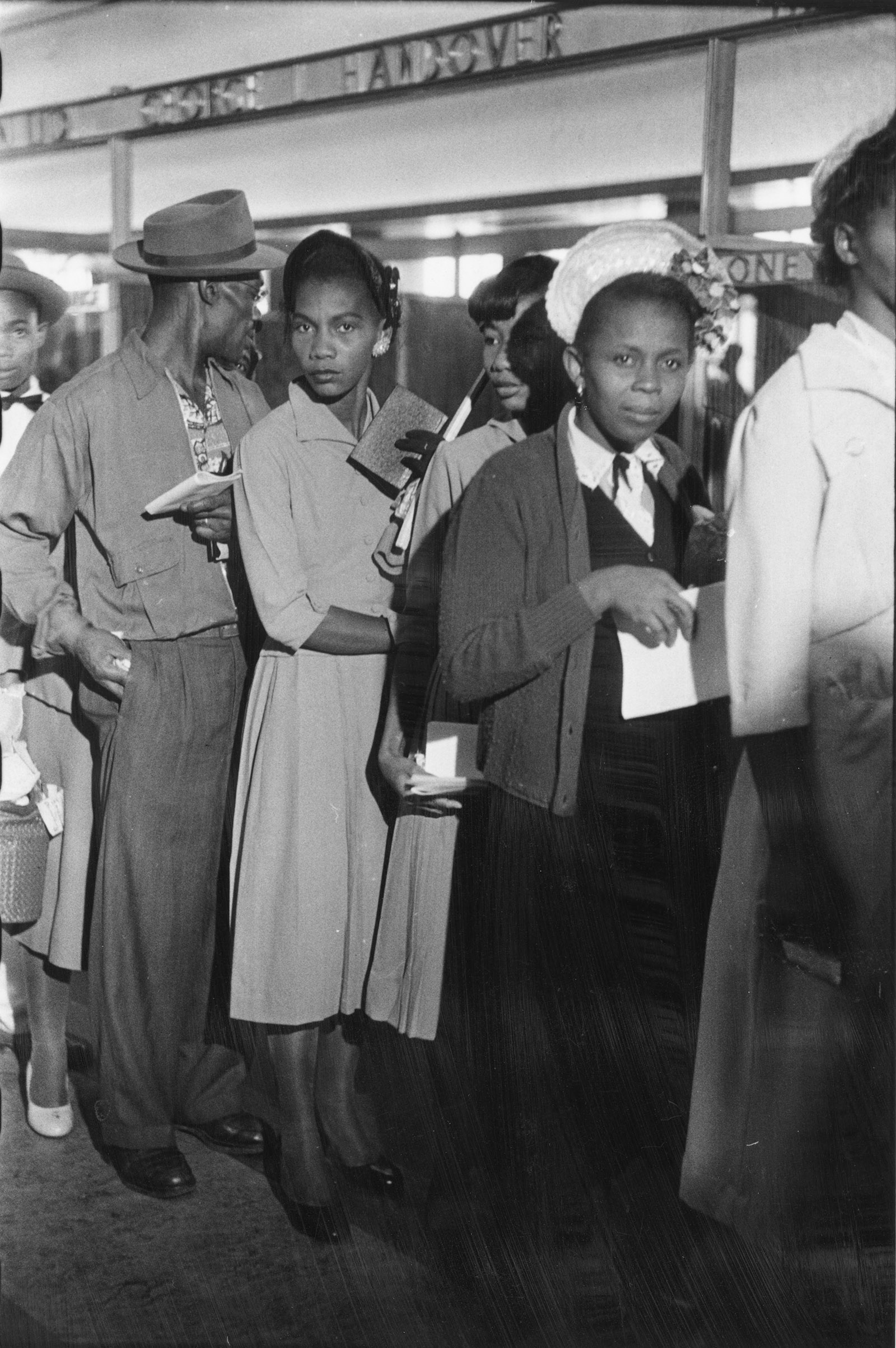

The government’s inhospitable, disloyal response to the Windrush descendants is a far cry from Britain’s attitude in the immediate postwar period, when the Ministry of Labour looked to address a serious labor shortage by inviting displaced Europeans, Irish, Asians, and West Indians to fill jobs that, in many cases, were then deemed undesirable by the indigenous working class. In the British West Indies, unemployment and low wages were rife—even for those whose briefcases were stuffed with diplomas—and in growing numbers young adults with a bit of bravado and enough money borrowed to travel decided to try their luck in Britain. Every time a plane took off or a boat sailed, it added to the fervor and determination of those left behind to do the same. At one stage, there were so many “gone to foreign,” as Jamaicans say, that it spawned a joke: the last one out should turn off all the lights on the Island. This was a trope taken up by the Jamaican poet and folklorist Louise Bennett, who saw a poetic justice in West Indians’ “colonizin Englan in reverse.”

In that first flush of mass migration, the 1948 British Nationality Act held open the door for any member of the Commonwealth to relocate to Britain. Many West Indians accepted the inducement, arriving on these shores with a five-year plan to save and prosper—to “work some money,” as they would have said—and then return to the islands. But their imagined temporary stay morphed into permanency, despite a rising tide of antipathy in the host nation—evident from the landlords’ adverts that specified “no blacks, no Irish, no dogs,” the violent gangs of “Teddy boys” who targeted Caribbean immigrants, and the labor unions that denied them membership.

Advertisement

In the beginning, young adults came over alone or, if married, with their partners. The expenses of the journey and resettling were such that, very often, children were left behind in the Caribbean in the care of relatives, to be sent for later when their parents could afford their passage. A year or two later, sometimes longer, those minors often traveled on a parent’s or adult sibling’s passport. The separations had been traumatic; often, the reunions were unsettling as well, with children joining parents who, in the interim, might have given birth to other children in Britain. The threat to the status and rights of this generation has added a new injury to these old scars.

David Lammy’s outraged speech came at important moment for the country. Earlier this month, the BBC astonished many listeners with its decision to dramatize and broadcast in its entirety (some forty-five minutes) Enoch Powell’s notorious 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech, one of the most toxic and incendiary anti-immigration statements ever delivered by a politician in Britain. The BBC argued that, in the current climate, it was important to mark the anniversary of the speech, and that the program provided a critique of that “dark moment in the nation’s history, which has shaped the immigration debate.” Indeed it did: Powell’s speech, framed as a dire warning to the country of the danger posed by high levels of immigration, fueled populist calls for the repatriation of migrants. In the years that followed, when I was growing up in Luton (some eighty-five miles south-east of Powell’s constituency), one of the most common insults hurled at West Indians and their descendants was “Why don’t you go back home!”

For me and my siblings, children of Jamaican immigrants, it led to an ambivalence in our relationship to the host nation. We lived a Caribbean version of W.E.B. Dubois’s “double consciousness”: we were the familiar strangers to Britain who both did and did not belong. Throughout my passage to adulthood, whenever I was challenged and asked “Where are you from?”, I would answer that I was British by birth but Jamaican by will and inclination. That formula is a luxury not available to those who find themselves under the present administrative hazard.

In retrospect, West Indians came not to colonize England in reverse, as Louise Bennett had it; rather, they decolonized England itself. Their influx heralded the end of the forelock-tugging tradition of working-class deference to social betters; they helped propel working-class culture from the margins to the center; and slowly, they forced Britain toward an accommodation with its imperial and colonial past. This sceptred isle has been fundamentally changed—for the better—by those from the Caribbean who, like Ulric Cross, answered the call of the motherland.

The British government’s current debacle—the result of poorly thought-through attempts to tighten controls in answer to anti-immigration hysteria—has also unnerved European residents in this country who fear for their post-Brexit status. If such shameful treatment can be meted out to the descendants of people who, for centuries, have been bound to Britain in a “special relationship,” then they fear what they and their children might face in the years to come.

When the BBC World Service shut down its “Caribbean Voices” show in 1958, it did so, officials said, because “the children had outgrown the patronage of the parent.” Notwithstanding Prime Minister Theresa May’s apology over the Windrush scandal, the British state cannot wash its hands of responsibility to the blameless children of the Windrush generation. They have outgrown the parent’s patronage, and repaid it many times over with their contributions to British society. It is Britain that is now indebted to them.