In 1944 Segundo Eloy Villanueva, the smart, stuttering seventeen-year-old son of a farmer in the foothills of the Peruvian Andes, learned that his father, Álvaro, had been murdered. Álvaro, riding a horse to a neighboring town to do some business, was shot by a neighbor whom he had recently reproached for allowing cattle to run riot in the family’s potato field. The neighbor also shot the man accompanying Álvaro. The police quickly found the bodies, led, some of the neighbors believed, by a five-centavo piece, the “coin of magic” that someone had left in the mouth of one of the corpses.

The magic worked, or maybe the search was easy: everyone in the area already knew about the cattle in the potato field. But justice moved slowly, over four years, and then was bought off. A judge released the murderous neighbor when Segundo was twenty-one. The son vowed revenge for his father, whom the neighbor “killed with a bullet, and I will kill him with my own hands, because he’s left us without our daily bread.”

The whole of Segundo’s inheritance was a trunk passed down from father to son across generations. Still in a rage and planning to seek vengeance on his father’s killer, inside the trunk Segundo found a Bible, written in Spanish. It would lead him on a decades-long process of conversion from his father’s Catholicism to Judaism—and from layperson to prophet. The decision to become a Jew came about unusually: he read the Bible carefully and thoroughly, excising the parts that didn’t seem to make sense, were contradictory, or lacked clear rules, until finally he decided to rip out the entire New Testament and bury it in the ground. Only the Old Testament was left. In The Prophet of the Andes, her thoroughgoing account of his journey, Graciela Mochkofsky writes of his decision to open the chest, “Looking back, it seems impossible for it to have been any other way, impossible that he would have chosen to kill instead.”

By the Israeli law of return, all Jews have the right to move to Israel and attain citizenship. The law was designed for those with at least one Jewish grandparent, and others have to prove that they are truly Jewish. The undertaking is a distant cousin to asylum seeking: How to prove one’s background and intentions, that one is not simply immigrating to a richer country for more opportunities? In 1990, as a middle-aged man, after moving first to the Peruvian Amazon and amassing a series of followers who joined him in intensive Bible study, Segundo managed not just to convert but to make aliyah—to “ascend”—and migrate to Israel. There he and his disciples joined a settlement in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, caught up in a fight over who counts as Jewish and in a demographic contest with Palestinians for the future of Israel.

Mochkofsky, a journalist born in Argentine Patagonia who is now based in New York City, is a contributing writer at The New Yorker and the dean of CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism. Her last name, she notes, immediately reads as Jewish in her home country. Her mother is Paraguayan Catholic, her father Argentine Jewish. She recounts Segundo’s quest with sympathy and simplicity. Mochkofsky has written numerous books of nonfiction in Spanish, including one on a railway crash that killed fifty-one people in Buenos Aires; one on the Argentine newspaper Clarín, which supported the military dictatorship of 1976–1983; and a critical biography of Jacobo Timerman, a Soviet-born newspaper editor who fled to Israel after imprisonment and torture in Argentina during the dictatorship and who is best known for his book Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number (1981). She has extraordinary range and a talent for injecting suspense into biography and accounts of family relations.

Mochkofsky grew up during the dictatorship and her first job was at the left-leaning independent newspaper Página/12 in Buenos Aires. In her book on Clarín, she describes Página/12 in the decade after the dictatorship as “direct, youthful, unmasked—which contrasted strongly with the euphemistic and ponderous tone of its rivals, still tied to the tone of the miliary era.” Mochkofsky has retained that directness and freshness of style. Calling things by their names, instead of using euphemism, still reads as a political statement, especially in her matter-of-fact discussion of disagreements over West Bank settlements among Jews. When she visited Kfar Tapuach in the West Bank, for example, where some Peruvians had settled, at least one settler told her that Palestinians should be further displaced to Jordan, Egypt, or Syria, and that if the Jews could only agree among themselves to push the Palestinians out farther, the conflict would be over.

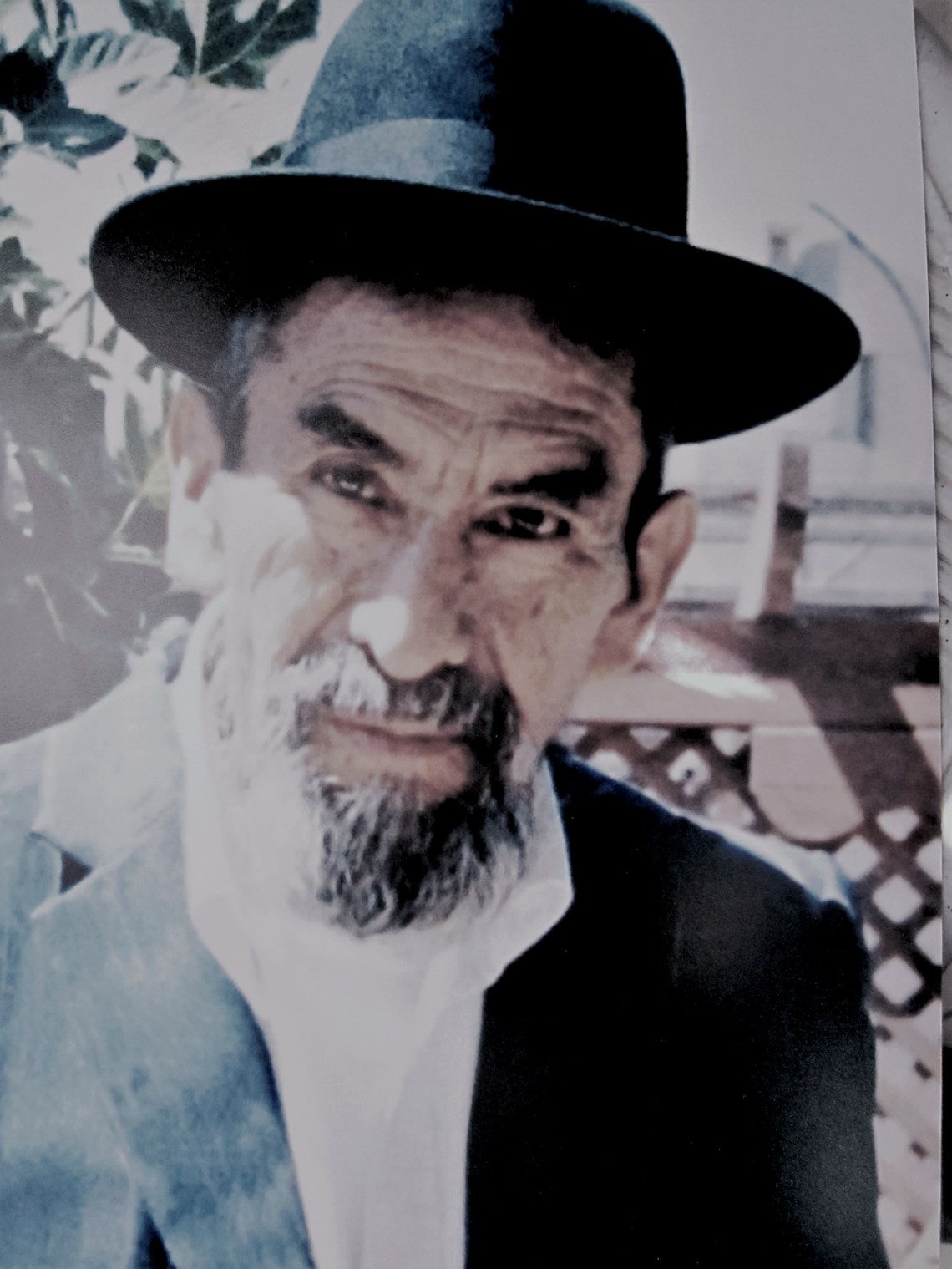

Mochkofsky smelled a story upon reading an account by a New York–based rabbi titled “Converting Inca Indians in Peru” and—despite its inaccuracies, exaggerations, and inventions—followed the trail all the way to a 2005 meeting with Segundo in Israel. She brought the family nearly ten pounds of yucca from Argentina at the request of his daughter, who wanted to cook a Peruvian dish. By then Segundo was called Zerubbabel Tzidkiya and had developed advanced Alzheimer’s. This meant, she writes, that “our awkward exchange could not be described as an interview.” She notes that the book, though, is dominated by the voices of men, since Segundo’s wife and daughters, who at first had spoken to her, later “decided to step back.” Segundo’s son continued to answer her questions and supply her with documents and photographs.

Advertisement

Mochkofsky first published a version of Segundo’s story in Spanish in 2007 under the title La revelación, but has now written an entirely new book on the subject, which has been expertly translated by Lisa Dillman into English. Mochkofsky condenses an astonishing sweep of religious and political history from the Spanish conquest to Zionism, connecting it to Segundo’s story with a light touch.

A Peruvian farmer’s son with a Bible in his hands may not sound all that surprising, but in 1944 it was taboo. The vast majority of Peruvians were Catholic—sometimes while maintaining Quechua or Aymara beliefs—and Segundo and his family were supposed to sit and listen to the Bible uncomprehendingly in church, where it was read out in Latin. “A Bible in one’s home was not illegal,” Mochkofsky writes, “but it was an act of arrogance; it was heresy, a sign of audacity or insanity.” It pierced the mystery of the word of God, before Vatican II allowed priests to give Mass in languages other than Latin in 1964.

Reading the Bible extinguished Segundo’s desire for vengeance. He was overcome with awe and a desire to follow God. The stories in the Bible seemed immediate and recognizable. “Despite the plethora of strange and wondrous events that occurred there, the land of Canaan sounded familiar to Segundo,” Mochkofsky writes. “It was the world of his father, of Rodacocha, of Milpoc”—the small farming communities where Segundo grew up—“full of donkeys and goats, roast lamb, udders and milk, crops harvested or ruined.” These were the usual dramas of village life: so-and-so begat so-and-so who lay with someone they shouldn’t have. The difference was that the people in the Bible were ennobled by following God. Segundo wanted that for himself.

He found the Bible both oddly familiar and deeply confusing. It seemed obvious that the Catholic priests lied, he thought, since Milpoc was full of false idols—the statues of saints that filled churches. Yet the Holy Book itself is a riot of fragments and contradictions. As a guide, it was baffling. Which rules from another era still applied? It was clear that Segundo should not kill, but how should he live? He found the New Testament especially vexing: “The tone was notably different; the content contradicted things previously said and at times defied common sense.”

Segundo began to gather a group of relatives to puzzle through the Holy Book with him. For a while they joined the Seventh-Day Adventist Reform Movement, which in Segundo’s opinion at the very least got the Sabbath right, since the Bible so clearly said it was not Sunday but Saturday—sábado in Spanish. The Adventists were just one of the many Protestant groups trawling Latin America then—a quarter of all Protestant missionaries landed there after 1949, when China closed its doors to them. The Protestants could not resolve his questions either. In Mochkofsky’s account, Segundo’s character emerges as stubborn and profound. “But why? Segundo wanted to know” is the refrain. Why was God one in the Pentateuch, an all-powerful oneness, then suddenly three later on? What exactly was the Holy Spirit if he, she, or it did not appear in the book?

Segundo’s close reading of the Bible took decades. He and his group left the Adventists and cast about for other options. In 1967, during his spiritual search, Segundo led some of his followers to a settlement in the Amazon, to be “closer to God and farther from man.” Refusing to work or receive wages on Saturdays had made it impossible to live normally, since Saturday was payday in Peru.

They built small wooden houses on stilts to keep the snakes out and, unlike most of the religious communities settling in the Amazon, did not bother their indigenous neighbors with their religious beliefs. Segundo became a serious autodidact, reading about different versions and translations of the Bible and taking two-day treks to Lima to visit the Bible Society, a branch of a nondenominational network that distributes inexpensive Bibles around the world. There he would consult different translations that confounded him with their inconsistencies. He decided to resolve the issue by learning Hebrew and reading the original text. At the Bible Society, he asked where he could find someone to teach him—and they pointed him to the Jews. Mochkofsky paraphrases his thoughts: “The Jews. Of course. The Jews!” Finally, he had lit upon a people who seemed to be living as God actually wanted. The chief rabbi of Lima welcomed an interest in Judaism and Hebrew but didn’t want to help anyone convert—not Segundo, not his followers.

Advertisement

Christianity encourages conversion, but conversion to Judaism is a difficult process by design. The Jewish community in Peru called itself “the colony” and shunned Segundo’s group, who by this point wanted to be Jews, even after a long period of study and negotiation with various religious authorities—and a set of circumcisions for men as old as eighty. Segundo’s followers might have stayed forever in the jungle were it not for a competition organized by the Israeli government.

Listening to the radio in the Amazon, the community learned of contests on biblical knowledge for those of any religious background run in every country where Israel had an embassy. The prize was an all-expenses-paid trip to Israel. A brilliant young member of Segundo’s group won thanks to a difficult question “sent like a ray of light from heaven” that he happened to have just reviewed—“Which king burned himself while setting fire to his palace?” In 1981 Prime Minister Menachem Begin welcomed him to Israel. At the Western Wall, he slipped between the stones a piece of paper with a wish that he would return to Israel with the rest of the Peruvians.

After the young man came back to Peru, Segundo and his followers doubled down on their Jewish practice. Segundo’s insistence on the primacy of the Torah meant following Orthodox strictures as far as he could ascertain them from reading. They hung mezuzahs and followed rigid rules in the jungle, from ritualized handwashing to reciting prayers in Hebrew at given times and sleeping on their sides, never on their backs or stomachs—as if they were all constantly pregnant. Despite an economic crisis in Peru, they scraped together money for an extremely modest synagogue, with “no roof, windows, bathroom, plaster, paint, doors, or furniture.” It was lit for prayers by candles and three kerosene lamps. Lacking money for a Sefer Torah, they photocopied the Torah and glued the pages to cloth scrolls. They renamed themselves Bnei Moshe (Children of Moses).

Still, they had a hard time finding actual Jews who wanted to help them convert. Eventually, they found aid abroad. Other groups claimed to be members of the lost tribes of Israel, which have been “found” in Afghanistan, Iran, China, and Kashmir, among other places. By the time Segundo and his group attempted to formally convert, messianic Zionists were becoming interested in Latin America. They considered it a divine mission to find and gather all “lost Jews” in Israel. These included the Marrano Jews forced to convert to Catholicism by the Spanish and Portuguese, some of whom fled to the Americas to continue to practice their original religion in secret.

The problem, however, was that the Bnei Moshe were not the lost Jews, nor were they Marrano Jews. Mochkofsky writes that they

made no reference to any past other than that of their faith, any blood other than that which coursed through their veins, any tales of candles lit in secret. They were not a lost tribe, nor did they wish to be. They were, simply, an enigma.

The big break for the Bnei Moshe came when word reached Eliyahu Avichail, a Zionist bent on finding the children of the ten tribes and returning them to Israel. The Israeli ambassador in Peru told the president of the Jewish Agency—a non-profit that has overseen the resettlement of over 3.3 million people to Israel since 1948—“you’ve got a group of goyim there who are more Zionist than the Jews.” The Jewish Agency didn’t ultimately follow up, but word spread and Israelis from a range of religious and political backgrounds started visiting Segundo’s group, and were moved by the simple outpost in the Amazonian Jungle. Avichail, after a visit, finally put together a beit din, a three-man council to judge if the Peruvians should be allowed to convert. In 1989, after warning that “the yoke of the Torah is quite heavy,” the council found that sixty-eight members of the community passed. It had taken decades, but now they were Jews.

If individual conversion to Judaism is difficult, group conversion of this sort is truly rare. There was the Abayudaya community of Uganda, which grew to include about two thousand Jews by the 1970s. There were the several dozen peasants in San Nicandro in Italy who declared that they were Jewish just as Italy introduced ever-harsher anti-Semitic laws during World War II, and who later immigrated en masse to Israel. Segundo’s community rounds out the list, as far as Mochkofsky can tell, along with a Pentecostal megachurch in Medellín, Colombia, whose leaders also became convinced that they were Jewish through Bible study, and which she wrote about for the late lamented California Sunday Magazine in 2016.

By Mochkofsky’s count, there are at least seventy similar communities of self-declared Jews—some formally converted, most not—in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Chile, and Bolivia. Those who haven’t converted are sometimes called “Judaizing Evangelicals.” For example, the ethnographer Manoela Carpenedo writes about a community of around 10,000 Brazilian evangelical Christians with no Jewish heritage who maintain Orthodox Jewish traditions including keeping kosher and building ritual baths in their backyards.* They still consider themselves Christians, since they follow Jesus, but emphasize the Jewish roots of the faith. The American pastor Bishop Wayne Jackson, who draped Donald Trump in a tallit during the 2016 presidential campaign—confusing and offending some US Jews—could be considered a Judaizing Evangelical too.

The Judaizing Evangelicals and those who convert outright to Judaism are still a relatively small phenomenon in the much bigger exodus in Latin America away from Catholicism, a flow that a well-liked Argentine pope has not stanched. The largest country in the region, Brazil, is set to become minority Catholic by 2030. Most Latin American ex-Catholics have converted to Pentecostalism, which preaches the so-called Gospel of Prosperity, quite a change in a region that saw the birth of liberation theology within Catholicism and its “preferential option for the poor.” Pentecostalism attracts followers from all over Latin America with prohibitions on alcohol, groups for intensive Bible study and community service, and lively music.

Foreigners arriving in certain poor areas of the Andes or Central America could be forgiven for thinking they have landed in a heavily Jewish place—six-pointed stars are everywhere. As around the US, there are churches called Israel, churches called Zion. These are Pentecostal symbols and names, but some groups draw on Jewish history or imagery. In 2014 Brazil’s largest Pentecostal group, the notoriously corrupt Assemblies of God, built an outsized replica of the Temple of Solomon in São Paulo as a megachurch seating 10,000 with a conveyor-belt system for tithes. The walls are decorated with menorahs. These Pentecostals, along with many in the US, are fervent Zionists who believe that Jews gathering in Israel is a precondition for the end-time—great for the Christians, since it will be the much-desired rapture, not so much for Jews, who must either convert or go straight to hell. On the annual Day of Prayer for the Peace of Jerusalem, thousands of churches worldwide pray for Israel. The largest Zionist organization in the Americas—with over 10 million members—is Christians United for Israel. Israeli settlers raise money from Pentecostal groups, helping subsidize the settlements illegally occupying Palestinian lands in the West Bank.

The strange convergence between messianic Zionists and their Pentecostal backers opened a door through which Segundo’s group was swept into modern Israel. Mochkofsky’s tale until this point has the kind of inevitable progression of a fable, but here the story becomes more tangled.

After the Bnei Moshe’s official conversions, they were cleared to make aliyah. On February 28, 1990, Segundo and his followers stepped off a plane into Ben Gurion Airport and spontaneously broke into song and dance. In Israel, they became known as the Peruanim. As resettlement authorities from the Jewish Agency drove them by bus into the desert, one of the Bnei Moshe asked about the accompanying convoy of armed soldiers. “This is the way we live here,” he was told. They awoke in Elon Moreh, a settlement of five hundred people on a fenced hill surrounded by Arab towns in the West Bank. One of their former allies who had come to see them in the jungle refused to visit them there because it was built on land seized by the Israel Defense Forces from two Palestinian villages—Azmut and Deir al-Hatab. Four days after they arrived, the Associated Press reported:

The tribe’s move to the occupied lands comes at a time of growing US pressure on Israel to stop building or expanding Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and demands that Israel not settle Soviet Jews in those areas.

The Bnei Moshe had finally seen their wildest dreams come true, and stepped right into the First Intifada. As the violence escalated, one Israeli journalist asked if the Peruvians were there as “part of a ‘desperate maneuver’” that involved “using the poor from other parts of the planet as cannon fodder” against the Palestinians. Others griped that the country was already filling up with Soviet Jews who were Jewish in name only—not to mention the Falasha, the Ethiopian Jews who were received by some Israelis with kindness, by others with overt suspicion.

The Colombian Jews Mochkofsky reported on also made aliyah, with the help of Shavei Israel, a right-wing organization best known for resettling in Israel a group from India that claims to be descended from one of the ten lost tribes. Shavel Israel’s leader, Michael Freund, grew up on the Upper East Side and moved to Israel in 1995. There he worked as deputy communications director in Benjamin Netanyahu’s first administration. He and his organization now promote “Greater Israel”—the idea that the West Bank and Gaza are part of the State of Israel by divine right. Shavei Israel helps lost, found, and self-declared Jews around the world move to Israel, which it considers a “tremendous opportunity to reinforce [the Jewish people’s] ranks,” according to its website, which laments a “demographic and spiritual crisis of unprecedented proportions”—the former a not-so-subtle reference to Palestinian family size. Shavei Israel also helped other Peruvians—even those thought by the original Peruanim to be merely seeking jobs and comforts unavailable at home—convert and emigrate, until they numbered around five hundred in the settlements. Freund’s efforts have been slowed by his estranged wife’s allegations three years ago that he transferred over $14 million without her consent or knowledge to Shavei Israel.

The Peruanim told Mochkofsky that they experienced culture shock upon arriving in Israel. Peruvians they knew back home tended to speak softly, with excessive politeness. Now, “people got right in one another’s faces, as if they were going to fight, even if nothing happened.” Segundo, for one, brought his usual querulous habit of questioning along with him to his new country. He found the Chabad-Lubavitchers, who believe that Rabbi Menachem Schneerson was the Messiah, “flat-out idolatrous.” He was sad to see that the Peruanim drifted apart—attracted by and marrying into different groups: kippa sruga, nationalist Orthodox Jews who serve in the army; Haredim, who do not; and others. Segundo along with several others ended up moving to a settlement known for following Meir Kahane, an American-born Orthodox rabbi who advocated for terrorist acts against “enemies of the Jewish people.” (One of Kahane’s followers assassinated Yitzhak Rabin after he signed peace agreements with Palestinian authorities.) Two Peruanim who lived there were shot by Palestinian snipers when at work driving buses in the settlement. Segundo himself continued discussing and arguing about spiritual matters with anyone who crossed his path, and seeking out people his hosts and handlers wished he wouldn’t: the Karaites of Ramla, who do not recognize the Talmud’s legal authority, and the Samaritans of Mount Gerizim, who consider that location—not Jerusalem’s Temple Mount—the chosen location for a holy temple.

Mochkofsky pointedly avoids telling the reader how to interpret this story. Were the Peruanim exploited by enthusiastic proponents of settlements in Palestine, or did they exploit right-wing nationalism to get what they wanted? Or was it a bit of both? “It is a story that I often thought I’d understood and then realized I had misunderstood,” she writes, “a story that seemed to have one ending and then turned out to have another. A story that, nearly two decades later, I still find incredible.”

This Issue

March 9, 2023

Peddling Darkness

Having the Last Word

Private Eyes

-

*

Manoela Carpenedo, Becoming Jewish, Believing in Jesus: Judaizing Evangelicals in Brazil (Oxford University Press, 2021). ↩