In 2001, at twenty-four, after spending much of my adolescence and young adulthood as a drug dealer, I shot and killed a man on a Brooklyn street. I was convicted and sentenced to twenty-eight years to life. I learned how to write in Attica, in a creative-writing workshop. I learned to live with what I did, on the page.

In 2018, after I had been transferred to Sing Sing, I received a letter from a producer of a true crime show on the cable network HLN. I knew of the producer’s work—she’d created a website called prisonwriters.com—and I figured she had my best interests in mind. She didn’t. Her colleagues visited me at Sing Sing and told me that their program, called Inside, was about redemption, and that the host, Chris Cuomo, wanted to talk to me about becoming a journalist in prison.

I soon learned that the full name of the show was Inside Evil. Cuomo and I did talk about redemption and my career, but during our interview he first wanted me to retrace the night of the murder. The episode that resulted used all the lurid tropes of true crime movies: close-ups of my mug shots; shadowy, slow-motion reenactments of the shooting; scary background music.

As a journalist who covers criminal justice while living in prison, I’ve been thinking a lot about the crime stories we tell for the purposes of entertainment. Sarah Weinman’s new book, Scoundrel, about the prison writer Edgar Smith, is one that will make people rethink the subset of true crime stories that could be called “true innocence”: stories that center on claims of wrongful convictions.

To me, true innocence is the more meaningful sliver of the traditional true crime genre, which merely retells terrible tales of violence. With true innocence stories, the audience is drawn to moral uncertainty: an incarcerated person, declaring innocence, may be either the victim of an injustice, or, salaciously put, a calculating psychopath. Scoundrel is traditional true crime that exploits true innocence.1 Weinman describes this as a “story of a wrongful conviction in reverse,” but also a “forgotten part of American history at the nexus of justice, prison reform, civil rights, neoconservatism, and literary culture.”

Weinman is the crime columnist for The New York Times Book Review. Her first book, The Real Lolita: A Lost Girl, an Unthinkable Crime, and a Scandalous Masterpiece, traced the similarities between the plot of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and the 1948 abduction of eleven-year-old Sally Horner. Her interest in crime and all its grisly details is not un-self-aware; in her editor’s note for an anthology called Unspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit, and Obsession, she acknowledges the “problems inherent to what I think of as the ‘true crime industrial complex,’ which turns crime and murder into entertainment for the masses.” With Scoundrel, she spins this yarn of human darkness nevertheless.

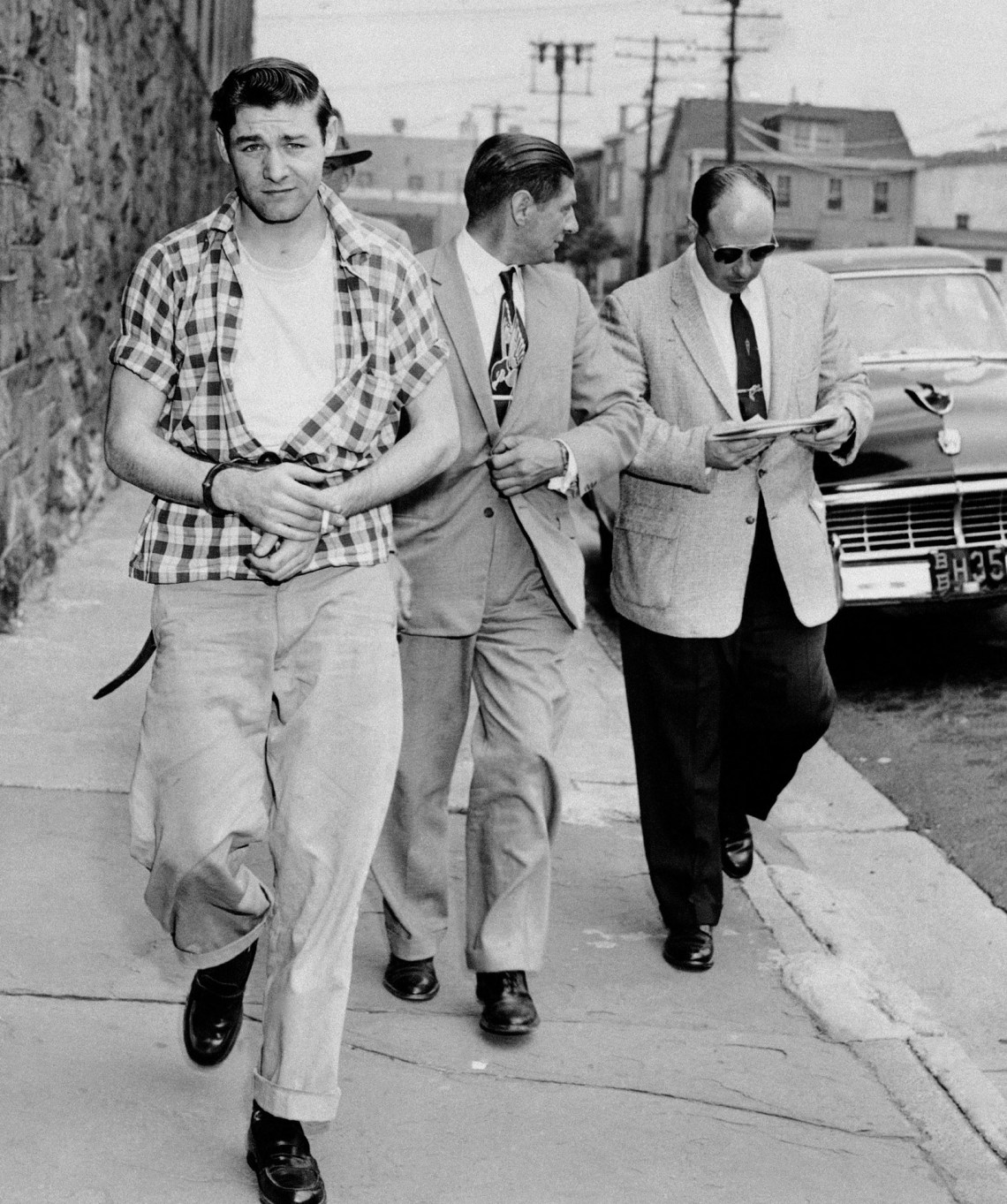

In the winter of 1957 Edgar Smith, a white twenty-three-year-old former marine living in Bergen County, New Jersey, with a wife and newborn, was driving down a dimly lit road when he saw a fifteen-year-old named Victoria Zielinski. He knew Zielinski from town and had given her rides in the past. On this night, he bludgeoned her to death and dumped her body in a sand pit on the side of the road. He confessed to the crime. A conviction and a death sentence soon followed.

In the beginning of the book, Weinman situates herself firmly on the side of the victim. This passage is a shot to the gut, especially for this reader, because it forces you to feel the true loss caused by murder. “The tragedy of early, violent death is that it strips away the person and leaves only the act, the making of the dead girl, rather than the celebration of the lived life,” Weinman writes.

The killer has the power. The one who dies loses it all. Victoria Zielinski not only lost her future, her power, and her promise on the night of March 4, 1957: she lost her existence, overridden by the needs and wants and desires of the man who murdered her.

It’s an important point to make, because the man who murdered this girl got to make a life for himself as a successful writer. This is something I know about: the man I killed was twenty-five. Even though I’ve only experienced it thus far from a prison cell, this writing life I’ve built for myself—this voice I’ve developed, today at the age of forty-five—is meaningful. It feels dishonest of me, as I go on writing this review, not to acknowledge that the man I killed could have had a meaningful life, too, had I not ended it so early.

Smith was sent to the Death House in Trenton State Prison. When you’re sentenced to life in prison, or condemned to die, the time after sentencing paradoxically takes on more of a purpose. It is still life. You’re fighting to exist, to matter. This applied to most men who lived on the death row tier with Smith. And they, like Smith, claimed they were innocent.

Advertisement

An ambitious autodidact, Smith knew he had to educate himself: “to turn his back,” Weinman writes, “on his old, shiftless self.” He read, he wrote, he took a correspondence course in accounting.

His chances of avoiding execution were slim, but there were some people still rooting for him. In 1962 Smith’s former high school football coach wrote a column in a local paper describing Smith’s daily routine. It included reading the National Review—at least until the chaplain who gave him the magazine moved on to another part of the prison. William F. Buckley, the National Review’s founder, was shown the column; he wrote Smith and offered him a free subscription. Smith, here, may have seen a way out.

Smith and Buckley became pen pals and, as Buckley recognized Smith’s literary talent, friends. Smith took the opportunity to tell his powerful new ally that he was an innocent man. Buckley published an article in Esquire casting doubt on Smith’s conviction, and used the fee for his legal defense fund. He introduced Smith to a Knopf editor, Sophie Wilkins, who helped him shape the book Brief Against Death (1968), presented as a memoir, in which Smith blames someone else, a nineteen-year-old named Don Hommell, who worked at a local pharmacy, for Zielinski’s murder.

In 1971, with Buckley’s influence, Smith’s murder conviction was overturned on the grounds that his unsigned confession was unconstitutional because it was coerced. Around the same time, New Jersey abolished the death penalty. In order to avoid another trial, the prosecution essentially offered Smith time served if he pleaded guilty to the murder. Smith took the deal, and after the fourteen-plus years he’d already served, walked out of the Death House and into a limousine with Buckley. They drove straight to a studio and filmed an episode of Firing Line, Buckley’s weekly TV show, in which he portrayed Smith as the picture of innocence.

It made me bitter to read about Smith’s return to society—shopping, visiting the National Review office, the press in tow—because I knew it ended badly. Brief Against Death sold well. He sold a novel, A Reasonable Doubt, to a different publisher. With the advances and royalties from these books he rented an apartment on the Upper West Side, where he racked up (paid) speaking engagements, wrote for the Times and Playboy, even bought a gold Cadillac. In 1974, at forty, Smith met a nineteen-year-old named Paige Hiemier, also from Bergen County. They moved to San Diego and married.

Weinman sums up these years as if she were writing the log line for a Hollywood noir called The Saga of a Bad Man, which is the title of one of her chapters. “As a result of Buckley’s advocacy,” she writes,

Edgar Smith vaulted from prison to the country’s highest intellectual echelons as a best-selling author, an expert on prison reform, and a minor celebrity—only to fall, spectacularly, to earth when his murderous impulses prevailed again.

That downfall started on September 30, 1976, when Smith asked for a staff position at The San Diego Union and was turned down. The next day, Smith kidnapped a thirty-three-year-old seamstress named Lisa Ozbun as she left work. He threw her in a car at knifepoint. Ozbun fought back and pulled the wheel. As the car veered off the freeway, she later testified, she managed to jump out—but not before Smith shoved a knife into her stomach.

Smith went on the run and told his wife and friends that he had been trying merely to rob Ozbun. From a hotel in Las Vegas, he called Buckley’s secretary. Buckley promptly gave up Smith’s whereabouts to the FBI. Weinman surmises that Smith was being manipulative when he got on the stand during his 1977 trial in San Diego and tearfully admitted that he tried to rape Ozbun. “At the time, in California,” she writes, “kidnapping with rape as the motivation could garner a lesser prison sentence, with the possibility of parole, while kidnapping in order to rob did not.”

As for Victoria Zielinski—Smith admitted that he had been guilty of killing the girl all along. “I recognized that the devil I had been looking at for the last forty-three years was me,” Smith told the court. He got life in prison without the possibility of parole. Buckley, and almost everyone else, abandoned him. In 2017, at the age of eighty-three, Smith died in a California prison medical facility.

Advertisement

Scoundrel is a triumph of archival research, and Weinman’s reporting and attention to detail are impressive, though often this means the book reads like a patchwork of letters exchanged between her trio of subjects: Smith, Buckley, and the Knopf editor Sophie Wilkins. Weinman connects the letters she excerpts with writing that is clear, but about half the book is material quoted from them and from old newspaper articles, which slows down the story. Then again, the most powerful writing in the book comes from those letter writers themselves.

At one point Buckley writes, “My God, I wish I could be absolutely certain you hadn’t killed that girl.”

“My God, I wish you could be absolutely certain I didn’t kill that girl,” Smith responds, with great guile.

I think, for now, that I am satisfied that you aren’t certain that I did kill her. Besides, do you really think it would do any good for me to tell you I didn’t? Would that convince you? Disclaimers of guilt are a dime a dozen around this place. From an idealistic point of view, if you are uncertain about my innocence, it follows that you must be uncertain about my guilt, as well, and I am entitled to the full benefit of your doubt. Where is your conservative belief in established judicial principles?

These exchanges, though witty and oddly light, get at the heart of the story: murder and doubt and belief. But when it comes to Smith’s correspondence with Wilkins, Weinman seems less an archivist than a voyeur. Smith’s relationship with Wilkins grew sexual, and their letters became lewd. (Reading Wilkins’s archived letters in a library, Weinman told the Know Your Enemy podcast, “crystallized this project as a book.”) Smith referred to their letters as epics. They were single-spaced twenty-plus-page missives sent through confidential legal mail to avoid guards reading them. In one letter, Smith measures his penis with a ruler; in another, he claims to be an expert in cunnilingus.

“Sophie did not keep copies of her own ‘epics,’” Weinman writes. “She likely destroyed them out of a growing sense of embarrassment and shame, as well as fear that someone else might read them.” (Or that someone, like Weinman, might publish them.) Somehow Weinman did convince Wilkins’s son Adam to share his mother’s letters from Smith, which she kept. Christopher Buckley, William’s son, initially denied Weinman’s request in 2015 to access his father’s archives at Yale, and then, four years later, approved it. (After reading her book, I imagine both men regret their decisions.)

Weinman’s story is animated, she writes, by women who were “sacrificed on the altar of the literary talent of a murderer.” Of course Wilkins, a woman, helped to shape that talent, and in some ways benefited from it. Wilkins had started at Knopf as an assistant in 1959, at the age of forty-four, which was somewhat unconventional; she was considered a bit of an outsider in the office. Acquiring books was difficult, and in 1965, when she read Buckley’s piece about Smith in Esquire, she was looking to bring in a big title.

A couple of years before Smith died, Weinman struck up her own correspondence with him, asking for an interview. By then she was already down the rabbit hole, having read countless newspaper articles, court transcripts, psychiatric records—and had concluded that Smith was a straight-up sociopath. To me, this doesn’t seem like she was approaching her subject with a journalist’s open mind. Maybe it’s my circumstances—I don’t have access to the Internet—but when I write about people who are in prison, I’m not influenced by immersion in tabloid stories about them.

Weinman’s letters, excerpted in the book, needle the eighty-year-old Smith, and he seems to bait her in return. She tells him that Buckley’s son Christopher was “not your biggest fan.” Weinman quotes Smith’s “blistering and blustery” reply: “To begin with, I don’t give a rat’s furry ass what Christopher Buckley likes or dislikes. Mama’s boys do not interest or impress me.” Once Smith realized Weinman was gearing up to write a book, he wrote, “I doubt we have anything more to discuss.” Weinman did not reply.

Did Weinman sabotage her own access? She seems hardly interested in Smith as a human being, and certainly not in hearing his own account—even though she was working on a book about his life. She calls the letter she wrote him “perfunctory.” In this, as I see it, she misses the real story. A more honest and substantive account would not have spent seventy or so pages on the racy relationship between a man on death row and a Knopf editor. To me, the real story is the one about a talented and damaged man sentenced to death and a compassionate conservative who was a proponent of the death penalty.

Reading Weinman’s book today, as our country continues to execute people, I wanted to hear more about what Buckley discovered in Smith, a man waiting to be electrocuted to death. Was Buckley more drawn to Smith’s potential innocence or his literary talent—and what does this say about human potential, and the risk that comes with cultivating it?

It bothers me that Buckley is ridiculed for getting so close to Smith. In a Q&A in the New York Law Journal, Weinman said the story was “about the power of belief and what happens when it’s given over to the wrong person.” I disagree. I believe Buckley knew all along that he might be befriending a murderer—“I wish I could be absolutely certain,” he wrote, meaning he wasn’t. That’s the tension in this story. Buckley, the conservative, knew Smith as a three-dimensional character. Weinman, the liberal, didn’t know him at all—plus she comes to the story with the benefit of knowing its unhappy end. She invested no personal stakes. At least Buckley took a shot. He befriended the man and risked his reputation by publicly advocating for his release.

It was hard for Buckley to come to terms with the situation in public, especially after it was revealed that Smith had been guilty all along. Instead, Buckley rationalized his support of Smith. “‘This year and every year’ guilty men are freed and innocent men are convicted,” Weinman notes that he wrote in his syndicated column. He never admitted to having considered the possibility that Smith was lying. Still, I admire Buckley’s respect for human dignity.

Weinman enters Smith’s story through that of the better-known prison writer Jack Henry Abbott. A few years ago I wrote for this magazine about Abbott and my thoughts about his actions. Abbott ingratiated himself with Norman Mailer, became a best-selling author, and, in 1981, only six weeks after his release, killed again.2 Mailer, like Buckley, was burned.

I struggled to write about Abbott. Not only did his post-release murder take a life, it also took something from me: it set prison writers back a generation, casting us as untrustworthy narrators. Now, with Scoundrel, I feel Weinman dredged up the Edgar Smith story because, as she acknowledges on Know Your Enemy, it was even more awful than Abbott’s. Abbott was a state-raised convict (his words). Smith was a predator. But he was also a writer who found his voice in prison by cultivating relationships with brilliant people, like Wilkins and Buckley, even though those relationships were built on lies.

It is true that Smith largely stopped writing after he returned to prison. But in 1998, after being back inside for more than twenty years, he came out with another book, A Tale of Old San Francisco. (It was published by a vanity press, with only limited copies printed.) He wrote to Buckley to tell him about the book. Buckley, his famous old friend, still showing class, sent a reply. It’s at this point that Smith, with a crushed soul, apologizes to Buckley, in a letter that Weinman, to her credit, excerpts.

“I do not like being in prison,” Smith writes, “and less so do I like the reason I am in prison, but I have adapted and found a sort of haven from any danger of rejection, except perhaps fatal self-rejection.” What does he mean when he says he dislikes the “reason”? Perhaps he’s referring to the shame, especially within the prison’s social hierarchy, that comes with hurting a woman, not to mention killing a child. Smith continues his letter to Buckley:

I will say, however, for what it is worth to you, that I deeply regret my betrayal of your extraordinary friendship. Perhaps Dante should have set aside a small corner of The Ninth Circle for people like me, those who so carelessly safeguard relationships of great value. You deserved better, as did so many others.

I am afraid that Abbott’s and Smith’s stories will be read as cautionary tales for public figures, writers, and other mentors who want to cultivate potential in other prison writers. Beyond my own unfortunate experience with Inside Evil and the true crime industrial complex, maybe Weinman’s book bothered me because today we’re experiencing a renaissance of prison writing—and I feel that her story casts a dark cloud over these emerging voices.

What made Smith an anomaly was not that he was a brilliant writer; it was what he did when he got out. The vast majority of us will never kill again. (A Stanford Criminal Justice Center report tracked 860 people convicted of murder in California and released since 1995 and found that only one percent committed new felonies, none of which were murder.) I want the other compassionate conservatives out there today, the ones in the vein of Buckley—and they exist—to know this. Without them, without you all, we will never get the criminal justice reform we need.

To be clear, I’m not looking to take an idealistic position on what punishment Smith did or didn’t deserve. I recognize what he did, what choices he made. What I’m interested in is what readers take away from books like Scoundrel—and the impetus for writing such a book. At the end of Scoundrel, Weinman writes that Smith’s “wrongful exoneration and the accompanying adulation obscured the damage inflicted upon so many women…. [He] hated women, and when he had the chance to hurt them, rape them, or kill them, he did.” I imagine many readers will finish Scoundrel and find Buckley complicit in Ozbun’s attempted murder. They will think the real injustice was that Smith wasn’t executed. Few will consider that Smith, who had spent nearly fifty-five years of his life in prison and, at eighty-three, had diabetes and had undergone six bypass surgeries, may not have deserved to die in one.

In the early 1970s, when Smith walked off death row after serving fourteen years for a murder, some 300,000 people were incarcerated in the US. By 2008 the prison population had jumped to 2.3 million. (It’s recently dipped to around 1.9 million.) In the 1970s, you served about seven or eight years for murder; today it’s around seventeen or eighteen.

Considering what a punitive time we live in, it’s unfortunate that Weinman chose to write a book about the Smith and Buckley saga that, more than anything, increases a reader’s thirst for punishment. What are the consequences of illuminating human darkness for entertainment? When we do this, do we hinder the progress of writers who focus on criminal justice reform?

I work with Emily Bazelon, a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine, on the Prison Letters Project at Yale Law School, where she is a lecturer. In response to her criminal justice writing over the years, she’s amassed a pile of letters from prisoners pleading with her to publicize their cases. I’ve received similar letters in prison from prisoners. With the help of Emily’s law students, we’ve organized the letters, followed up with questionnaires, and started to select cases to highlight. The majority of letter writers are Black; some are on death row, some are serving life sentences, and some are surely lying in their letters. As I see it, that’s an act of self-preservation. I’m not reading these letters thinking manipulative psychopaths are trying to con me; I see desperate people who want to live and want out. I get it.

Weinman evinces a solid understanding of criminal justice issues, but neither this book nor her larger body of work includes even one hard-hitting investigation of an injustice of the legal system or, say, an exploration of a character who is trying to overcome prison or the difficulty of reentry. In Scoundrel’s introduction, she positions herself as an advocate:

When police brutality and mass incarceration are perennially under a national microscope, when the lives of countless Black and Brown boys and men are permanently altered by the criminal justice system, the transformation of Smith into a national cause more than half a century ago raises uncomfortable questions about who deserves a spotlight and who does not. His story, and the involvement of the many people who helped fashion it, complicates the larger narrative of incarcerated people who proclaim their innocence and of prisoners—on death row and elsewhere—exonerated and freed thanks to newly discovered or long-suppressed evidence.

Yet as the book proceeds, this attempt to bring her story in line with the language of antiracist criminal justice reform begins to feels forced, as though Weinman is pandering or trying to check an obligatory ethical box before telling a conventional true crime story.

Legal experts conservatively estimate that 4.1 percent of death sentences are wrongful convictions; the report stipulates that many will never be discovered. The way Weinman tells Smith’s story—bringing attention to this fairly obscure story at all—may complicate the claims of innocence of incarcerated people today. In the end, it’s her righteous indignation that makes me cringe: the liberal true crime writer who warns us about the terrible state of our criminal justice system while producing the kind of work that seems only to justify its existence.

This Issue

March 9, 2023

Having the Last Word

Private Eyes

-

1

The subtitle of the original hardcover edition spelled it out: “How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free.” ↩

-

2

See my “The Murderer, the Writer, the Reckoning,” nybooks.com, July 9, 2019. ↩